|

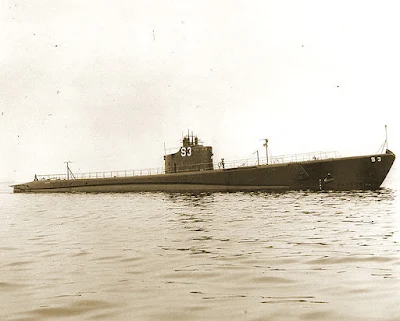

| Skipjack during trials, off Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States, 14 May 1938. |

USS Skipjack (SS-184), a Salmon-class submarine, was the second ship of the United States Navy to be named after the fish. Her keel was laid down by the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut, on 22 July 1936. She was launched on 23 October 1937 sponsored by Miss Frances Cuthbert Van Keuren, daughter of Captain Alexander H. Van Keuren, Superintending Constructor, New York Navy Yard. The boat was commissioned on 30 June 1938. She earned multiple battle stars during World War II and then was sunk, remarkably, by an atomic bomb during post-war testing. Among the most "thoroughly sunk" ships, she was refloated and then sunk a second time as a target ship two years later.

Pre-World War II Service

Following shakedown in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea and post-shakedown repairs at New London, Connecticut, Skipjack was assigned to Submarine Squadron 6 (SubRon 6) and departed for fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean and South Atlantic. Following her return to New London on 10 April 1939, she sailed with sister ships Snapper (SS-185) and Salmon (SS-182) for the Pacific, transited the Panama Canal on 25 May, and arrived at San Diego, California, on 2 June. During July, she cruised to Pearl Harbor as part of SubRon 2; returned to San Diego on 16 August; and remained on the West Coast engaged in fleet tactics and training operations until 1 April 1940, when she again got underway for the Hawaiian area for training exercises there. Following her return to San Diego, Skipjack underwent overhaul at the Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo, California, and then proceeded back to Pearl Harbor, where she was attached to Rear Admiral Wilhelm L. Friedell's COMSUBPAC, Pacific Fleet, as a member of SubDiv 15 (commanded by Captain Ralph Christie). She operated out of Pearl Harbor until again undergoing overhaul at Mare Island in July and August 1941. Skipjack returned on 16 August and commenced patrols off Midway Island, Wake Island, and the Gilbert Islands and Marshall Islands. In October 1941, SubDiv 15 (then commanded by "Sunshine" Murray) was transferred to ComSubAsiatic Fleet, along with the tender Holland, and Joe Connolly's SubDiv 16, as SubRon 2. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December, Skipjack was in the Philippines undergoing repairs at the Cavite Navy Yard.

First, Second and Third War Patrols

On 9 December, Skipjack (under the command of Charles L. Freeman) departed Manila on her first war patrol, with all unfinished repair work completed by her crew en route to the patrol area off the east coast of Samar. The submarine conducted two torpedo attacks during this patrol. On 25 December, in the first attack of its kind by a U.S. submarine, Skipjack attacked an enemy aircraft carrier and a destroyer. She followed prewar doctrine and fired three torpedoes on sonar bearings from a depth of 100 feet (30 m), without success. On 3 January 1942, three torpedoes were fired at an enemy submarine, resulting in two explosions, but a sinking could not be confirmed. She refueled at Balikpapan, Borneo, on 4 January and arrived at Port Darwin, Australia, for refit on 14 January.

Skipjack’s second war patrol, conducted in the Celebes Sea, was uneventful with the exception of an unsuccessful attack on a Japanese aircraft carrier. She returned to Fremantle, Western Australia, on 10 March 1942. On 14 April, Skipjack got underway under the command of James W. Coe for her third war patrol, conducted in the Celebes Sea, Sulu Sea, and South China Sea. On 6 May, contact was made with a Japanese cargo ship, and the submarine moved in for the kill. Finding herself almost dead ahead, Skipjack fired a "down the throat" spread of three torpedoes that sank the Kanan Maru. Two days later, the submarine intercepted a three-ship convoy escorted by a destroyer and she fired two torpedoes that severely damaged the merchant ship, Taiyu Maru. Then she let go with four more that quickly sank the cargo ship, Bujun Maru. On 17 May, Skipjack sank the passenger-cargo ship Tazan Maru off Indochina before heading back to Fremantle.

While in Mare Island Naval Shipyard on 11 June, Commander James W. Coe sent a notorious message to the yard's Supply Officer regarding the cancellation of his requisition for toilet paper. It had the salubrious result of never leaving Skipjack short of this vital supply for the duration. The story is told, and the notorious message reproduced in full, in Ned Beach's Submarine!. It likely inspired a very similar message sent by the fictional Commander Matt Sherman (Cary Grant) of USS Sea Tiger in the 1959 film Operation Petticoat.

Fourth through Ninth War Patrols

Following participation in performance tests for the Mark 14 torpedo, Skipjack sailed for her fourth war patrol on 18 July 1942, conducted along the northwest coast of Timor which she reconnoitered and photographed. She also severely damaged an enemy oiler. The submarine returned to Fremantle for refit on 4 September.

Skipjack’s fifth war patrol was conducted off Timor Island, Amboina, and Halmahera. On 14 October, while patrolling south of the Palau Islands, the submarine torpedoed and sank the 6,781-ton cargo ship, Shunko Maru. Following a depth charge attack by a Japanese destroyer, the submarine returned to Pearl Harbor on 26 November.

Skipjack’s sixth, seventh, and eighth war patrols were unproductive. But, during her ninth, conducted in the Caroline Islands and Mariana Islands areas, she sank two enemy vessels. On 26 January 1944, she commenced a night attack on a merchant ship, but, prior to firing, she shifted targets when an enemy destroyer began a run on the submarine. She quickly fired her forward torpedoes and was rewarded with solid hits that quickly sank Suzukaze. The submarine then fired her stern tubes at the merchant ship. One of the submarine's torpedo tube valves stuck open and her after torpedo room began to flood. The torpedomen were unable to close the emergency valves until she had taken on approximately 14 tons of water. A large upward angle developed almost immediately, forcing the submarine to surface. By the time control of the boat had been regained, the water in the torpedo room was only a few inches from the top of the water tight door, but fortunately there were no casualties, and Skipjack resumed the attack. The submarine then torpedoed and sank the converted seaplane tender Okitsu Maru. She returned to Pearl Harbor on 7 March.

Tenth War Patrol

Following repairs, Skipjack participated in performance tests on new torpedoes in cold water off the Pribilof Islands until 17 April and then headed for the Mare Island Navy Yard and overhaul. After returning to Pearl Harbor, Skipjack got underway for her tenth and final war patrol, conducted in the Kuril Islands area. During this patrol, she damaged an enemy auxiliary and attacked a Japanese destroyer without success.

Late War

On 11 December 1944, she returned to Midway Island and then continued on to Ulithi. She then sailed to Pearl Harbor for refit; and got underway on 1 June 1945 for New London, Connecticut, and duty training submarine school students.

Details

Builder: Electric Boat Company, Groton, Connecticut

Laid down: 22 July 1936

Launched: 23 October 1937

Commissioned: 30 June 1938

Decommissioned: 28 August 1946

Stricken: 13 September 1948

Fate:

Sunk in Operation Crossroads atomic bomb test, 25 July 1946

raised 2 September 1946; sunk as a target off southern California, 11 August 1948

Class and type: Salmon-class composite diesel-hydraulic and diesel-electric submarine

Displacement:

1,435 long tons (1,458 t) standard, surfaced

2,198 long tons (2,233 t) submerged

Length: 308 ft 0 in (93.88 m)

Beam: 26 ft 1+1⁄4 in (7.957 m)

Draft: 15 ft 8 in (4.78 m)

Propulsion:

4 × Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (H.O.R.) 9-cylinder diesel engines (two hydraulic-drive, two driving electrical generators)

2 × 120-cell batteries

4 × high-speed Elliott electric motors with reduction gears

two shafts

5,500 shp (4.1 MW) surfaced

2,660 shp (2.0 MW) submerged

Speed:

21 knots (39 km/h) surfaced

9 knots (17 km/h) submerged

Range: 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h)

Endurance: 48 hours at 2 knots (3.7 km/h) submerged

Test depth: 250 ft (76 m)

Complement: 5 officers, 54 enlisted

Armament:

8 × 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes (four forward, four aft)

24 torpedoes

1 × 3 in (76 mm) / 50 caliber deck gun

four machine guns

Fate

Skipjack was later sunk as a target vessel in the second atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll in July 1946 and was later raised and towed to Mare Island. On 11 August 1948, she was again sunk as a target off the coast of California by aircraft rockets. Her name was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 13 September 1948.

|

Commander |

From |

To |

|

Lt. Herman Sall, USN |

30 Jun 1938 |

mid 1939 |

|

Frederick Kent Loomis, USN |

mid 1939 |

13 Jul 1941 |

|

Lt. Charles Lawrence Freeman, USN |

13 Jul 1941 |

27 Mar 1942 |

|

Lt. James Wiggins Coe, USN |

27 Mar 1942 |

17 Jan 1943 |

|

T/Cdr. Howard Fletcher Stoner, USN |

17 Jan 1943 |

7 Sep 1943 |

|

T/Cdr. George Garvie Molumphy, USN |

7 Sep 1943 |

21 Sep 1944 |

|

T/Cdr. Richard Stottko Andrews, USN |

21 Sep 1944 |

22 Dec 1944 |

|

Frank John Coulter, USN |

22 Dec 1944 |

21 Aug 1946 |

Awards

Skipjack received seven battle stars for World War II service.

“Cannot Identify Material …”: USS Skipjack’s Expendable Material Requisition

Months before the war started, U.S.S. Skipjack (SS-184) had submitted a requisition for some expendable material essential to the health and comfort of the crew. What followed was, to the sea-going Navy, a perfect example of how to drive good men man unnecessarily. For almost a year later the Skipjack received her requisition back, stamped "Canceled—cannot identify material." Whereupon Jim Coe, skipper of the Skipjack, let loose with a blast which delighted everybody except those attached to the supply department of the Navy Yard, Mare Island, California.

This is what he wrote:

USS SKIPJACK

SS184/L8/SS36-1

June 11, 1942

From: The Commanding Officer.

To: Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island, California.

Via: Commander Submarines, Southwest Pacific.

Subject: Toilet Paper.

Reference:

(a)

(4608) USS HOLLAND (5184)

USS SKIPJACK reqn. 70-42 of 30 July

1941.

(b) SO NYMI canceled invoice No. 272836.

Enclosure:

(A) Copy of

canceled invoice.

(B) Sample of material requested.

This vessel submitted a requisition for 150 rolls of toilet paper on July 30, 1941, to USS HOLLAND. The material was ordered by HOLLAND from the Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island, for delivery to USS SKIPJACK.

The Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island, on November 26, 1941, canceled Mare Island invoice No. 272836 with the stamped notation "Canceled-cannot identify." This canceled invoice was received by SKIPJACK on June 10, 1942.

During the 11¼ months elapsing from the time of ordering the toilet paper and the present date, the SKIPJACK personnel, despite their best efforts to await delivery of subject material, have been unable to wait on numerous occasions, and the situation is now quite acute, especially during depth charge attack by the "back-stabbers."

Enclosure (B) is a sample of the desired material provided for the information of the Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island. The Commanding Officer, USS SKIPJACK cannot help but wonder what is being used in Mare Island in place of this unidentifiable material, once well known to this command.

SKIPJACK personnel during this period have become accustomed to the use of "ersatz," i.e., the vast amount of incoming non-essential paperwork, and in so doing feel that the wish of the Bureau of Ships for reduction of paper work is being complied with, thus effectively killing two birds with one stone.

It is believed by this command that the stamped notation "cannot identify" was possibly an error, and that this is simply a case of shortage of strategic war material, the SKIPJACK probably being low on the priority list.

In order to cooperate in our war effort at a small local sacrifice, the SKIPJACK desires no further action to be taken until the end of current war, which has created a situation aptly described as "war is hell."

[signed] J.W. COE

It is to be noted that Jim Coe was wrong in one particular—it had been only ten and a quarter months. But his letter, carrying in it all the fervor and indignation of a man who has received a mortal hurt, achieved tremendous fame.

It also achieved rather remarkable results back in Mare Island, although this was mostly hearsay. But one result was extremely noticeable indeed: whenever Skipjack returned from patrol, no matter where she happened to put in, she received no fruit, no vegetables, and no ice cream. Instead, she invariably received her own outstandingly distinctive tribute—cartons and cartons of toilet paper.

Jim Coe, a most successful submarine commander and humorist to boot, did not survive the war. After three patrols in command of Skipjack, he returned to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to place the new submarine Cisco in commission. On 19 September 1943, Cisco departed from Darwin, Australia, on her first war patrol, and was never heard from again.

Here is the rest of the story:

The letter was given to the Yeoman, telling him to type it up. Once typed and upon reflection, the Yeoman went looking for help in the form of the XO. The XO shared it with the OD and they proceeded to the CO's cabin and asked if he really wanted it sent. His reply, "I wrote it, didn't I?"

As a side note, twelve days later, on June 22, 1942 J.W. Coe was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions on the S-39.

The "toilet paper" letter reached Mare Island Supply Depot. A member of that office remembers that all officers in the Supply Department "had to stand at attention for three days because of that letter." By then, the letter had been copied and was spreading throughout the fleet and even to the President's son who was aboard the USS Wasp.

As the boat came in from her next patrol, Jim and crew saw toilet-paper streamers blowing from the lights along the pier and pyramids of toilet paper stacked seven feet high on the dock. Two men were carrying a long dowel with toilet paper rolls on it with yards of paper streaming behind them as a band played coming up after the roll holders. Band members wore toilet paper neckties in place of their Navy neckerchiefs. The wind-section had toilet paper pushed up inside their instruments and when they blew, white streamers unfurled from trumpets and horns.

As was the custom for returning boats to be greeted at the pier with cases of fresh fruit/veggies and ice cream, the Skipjack was first greeted thereafter with her own distinctive tribute-cartons and cartons of toilet paper.

This letter became famous in submarine history books and found its way to the movie "Operation Petticoat", and eventually coming to rest (copy) at the Navy Supply School at Pensacola, Florida. There, it still hangs on the wall under a banner that reads, "Don't let this happen to you!" Even John Roosevelt insured his father got a copy of the letter.

|

| USS Skipjack (SS-184) off Provincetown, Massachusetts during sea trials, 14 May 1938. |

|

| Skipjack during trials, off Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States, 14 May 1938. |

|

| Skipjack during trials, off Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States, 14 May 1938. |

|

| Skipjack during trials, off Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States, 14 May 1938. |

|

| Skipjack during trials, off Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States, 14 May 1938. |

|

| Skipjack during trials, off Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States, 14 May 1938. |

|

| Skipjack's data plaque, photographed circa June 1938. |

|

| Skipjack running up Thames River after departing the Electric Boat Company shipyard at Groton, Connecticut, United States to go to the Naval Submarine Base for commissioning ceremonies, 30 June 1938. |

|

| Condition of ship bottom paints: General view of Bow, starboard side, 11 July 1941. |

|

| Condition of ship bottom paints: General view Aft, port side, 11 July 1941. |

|

| Condition of ship bottom paints: Detailed view Aft, starboard side, 11 July 1941. |

|

| Condition of ship bottom paints: Detailed view Aft, starboard side, 11 July 1941. |

|

| LCDR Charles Lawrence Freeman was the commanding officer of the Skipjack (SS-184) from 29 July 1941 to 28 March 1942. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184) underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 22 March 1943. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184) underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 22 March 1943. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184) seen from ahead, while underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 22 March 1943. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184) seen from astern, while underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 22 March 1943. |

|

| Amidships looking forward plan view of Skipjack (SS-184) in Mare Island channel on 19 July 1944. She was in overhaul at the yard from 25 April to 26 July 1944. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184), off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 19 July 1944. |

|

| Port side view of the Skipjack (SS-184), underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 19 July 1944. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184), photographed from ahead, while underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 19 July 1944. |

|

| USS Chivo, USS Skipjack, and USS Parche at Pearl Harbor, US Territory of Hawaii, 1945. |

|

| Insignia designed for Skipjack (SS-184), during World War II. |

|

| Skipjack (SS-184), at South Boston Navy Yard, circa 15 November 1945 to 4 February 1946. |

|

| The U.S. Navy submarines USS Skipjack (SS-184) (inboard) and USS Skate (SS-305) at the Pacific Reserve Fleet at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, California, in October 1947. |

|

| Ex-Skipjack (SS-184), sinking off southern California, after being used as a target, 11 August 1948. Note her propellers, stern planes, rudder, and badly damaged after superstructure. |

|

Ships Sunk |

|||

|

# |

Name |

Type |

Distance from surface zero |

|

50 |

LSM-60 |

Amphibious |

0 yd (0 m) |

|

3 |

Arkansas |

Battleship |

170 yd (160 m) |

|

8 |

Pilotfish |

Submarine |

363 yd (332 m) |

|

10 |

Saratoga |

Aircraft carrier |

450 yd (410 m) |

|

12 |

YO-160 |

Yard oiler |

520 yd (480 m) |

|

7 |

Nagato |

Battleship |

770 yd (700 m) |

|

41 |

Skipjack |

Submarine |

800 yd (730 m) |

|

2 |

Apogon |

Submarine |

850 yd (780 m) |

|

11 |

ARDC-13 |

Drydock |

1,150 yd (1,050 m) |

|

| The original infamous requisition letter is at the Bowfin Museum in Hawaii. |