German submarine U-234 was a Type XB U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II. Her first and only mission into enemy territory consisted of the attempted delivery of uranium oxide and German advanced weapons technology to the Empire of Japan. After receiving Admiral Donitz’ order to surface and surrender and of Germany’s unconditional surrender, the submarine’s crew surrendered to the United States on 14 May 1945.

Originally built as a minelaying submarine, she was laid down at the Germaniawerft in Kiel on 1 April 1942; U-234 was damaged during construction but launched on 22 December 1943. Following the loss of U-233 in July 1944, it was decided not to use U-234 as a minelayer; she was completed instead as a long-range cargo submarine with missions to Japan in mind.

U-234 was one of the few U-boats that was fitted with a FuMO-61 Hohentwiel U-Radar Transmitter. This equipment was installed on the starboard side of the conning tower.

U-234 was also fitted with the FuMB-26 Tunis antenna.

U-234 returned to the Germaniawerft yard at Kiel on 5 September 1944, to be refitted as a transport. Apart from minor work, she had a snorkel added and 12 of her 30 mineshafts were fitted with special cargo containers the same diameter as the shafts and held in place by the mine release mechanisms. In addition, her keel was loaded with cargo, thought to be optical-grade glass and mercury, and her four upper-deck torpedo storage compartments (two on each side) were also occupied by cargo containers.

The cargo to be carried was determined by a special commission, the Marine Sonderdienst Ausland, established towards the end of 1944, at which time the submarine’s officers were informed that they were to make a special voyage to Japan. When loading was completed, the submarine’s officers estimated that they were carrying 240 tons of cargo plus sufficient diesel fuel and provisions for a six- to nine-month voyage.

The cargo included technical drawings, examples of the newest electric torpedoes, one crated Me 262 jet aircraft, a Henschel Hs 293 glide bomb and what was later listed on the US Unloading Manifest as 1,200 pounds (540 kg) of uranium oxide. In the 1997 book Hirschfeld, Wolfgang Hirschfeld reported that he watched about 50 lead cubes with 23 centimeters (9.1 in) sides, with “U-235” painted on each, into the boat’s cylindrical mine shafts. According to cable messages sent from the dockyard, these containers held “U-powder.”

When the cargo was loaded, U-234 carried out additional trials near Kiel, then returned to the northern German city where her passengers came aboard.

U-234 was carrying twelve passengers, including a German general, four German naval officers, civilian engineers and scientists and two Japanese naval officers. The German personnel included General Ulrich Kessler of the Luftwaffe, who was to take over Luftwaffe liaison duties in Tokyo; Kai Nieschling, a Naval Fleet Judge Advocate who was to rid the German diplomatic corps in Japan of the remnants of the Richard Sorge spy ring; Dr. Heinz Schlicke, a specialist in radar, infra-red, and countermeasures and director of the Naval Test Fields in Kiel (later recruited by the USA in Operation Paperclip); and August Bringewalde, who was in charge of Me 262 production at Messerschmitt.

The Japanese passengers were Lieutenant Commander Hideo Tomonaga of the Imperial Japanese Navy, a naval architect and submarine designer who had come to Germany in 1943 on the Japanese submarine I-29, and Lieutenant Commander Shoji Genzo, an aircraft specialist and former naval attaché.

U-234 sailed from Kiel for Kristiansand in Norway on the evening of 25 March 1945, accompanied by escort vessels and three Type XXIII coastal U-boats, arriving in Horten two days later. The submersible spent the next eight days carrying out trials on her snorkel, during which she accidentally collided with a Type VIIC U-boat performing similar trials. Damage to both submarines was minor, and despite a diving and fuel oil tank being holed, U-234 was able to complete her trials. She then proceeded to Kristiansand, arriving on about 5 April, where she underwent repairs and topped up her provisions and fuel.

U-234 departed Kristiansand for Japan on 15 April 1945, running submerged at snorkel depth for the first 16 days, and surfacing after that only because her commander Kapitänleutnant Johann-Heinrich Fehler, considered he was safe from attack on the surface in the prevailing severe storm. From then on, she spent two hours running on the surface by night, and the remainder of the time submerged. The voyage proceeded without incident; the first sign that world affairs were overtaking the voyage was when the Kriegsmarine ’s Goliath transmitter stopped transmitting, followed shortly after by the Nauen station. Fehler did not know it, but Germany’s naval HQ had fallen into Allied hands.

Then, on 4 May, U-234 received a fragment of a broadcast from British and American radio stations announcing that Admiral Karl Dönitz had become Germany’s head of state following the death of Adolf Hitler. U-234 surfaced on 10 May in the interests of better radio reception and received Dönitz’s last order to the submarine force, ordering all U-boats to surface, hoist black flags and surrender to Allied forces. Fehler suspected a trick and managed to contact another U-boat (U-873), whose captain convinced him that the message was authentic.

At this point, Fehler was practically equidistant from British, Canadian and American ports. He decided not to continue his journey, and instead headed for the east coast of the United States. Fehler thought it likely that if they surrendered to Canadian or British forces, they would be imprisoned and it could be years before they were returned to Germany; he believed that the US, on the other hand, would probably just send them home.

Fehler consequently decided that he would surrender to US forces, but radioed on 12 May that he intended to sail to Halifax, Nova Scotia to surrender to ensure Canadian units would not reach him first. U-234 then set course for Newport News, Virginia; Fehler taking care to dispose of his Tunis radar detector, the new Kurier radio communication system, and all Enigma related documents and other classified papers. On learning that the U-boat was to surrender, the two Japanese passengers committed suicide by taking an overdose of Luminal (a barbiturate sleeping pill). They were buried at sea.

The difference between Fehler’s reported course to Halifax and his true course was soon realized by US authorities who dispatched two destroyers to intercept U-234. On 14 May 1945 she was encountered south of the Grand Banks, Newfoundland by the USS Sutton. Members of the Sutton’s crew took command of the U-boat and sailed her to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where U-805, U-873, and U-1228 had already surrendered. Dr. Velma Hunt, a retired Penn State University environmental health professor, has suggested U-234 may have put into two ports between her surrender and her arrival at the Portsmouth Navy Yard: once in Newfoundland, to land an American sailor who had been accidentally shot in the buttocks, and again at Casco Bay, Maine. News of U-234’s surrender with her high-ranking German passengers made it a major news event. Reporters swarmed over the Navy Yard and went to sea in a small boat for a look at the submarine.

A classified US intelligence summary written on 19 May listed U-234 ’s cargo as including drawings, arms, medical supplies, instruments, lead, mercury, caffeine, steels, optical glass and brass. The fact that the ship carried .5 short tons (0.45 t) of uranium oxide remained classified for the duration of the Cold War. Author and historian Joseph M. Scalia wrote that he discovered a formerly secret cable at Portsmouth Navy Yard which stated that the uranium oxide had been stored in gold-lined cylinders. This document is discussed in Hitler’s Terror Weapons. The exact characteristics of the uranium remain unknown. Scalia and historians Carl Boyd and Akihiko Yoshida speculated that it may not have been weapons-grade material and was instead intended for use as a catalyst in the production of synthetic methanol for aviation fuel.

The 1,200 pounds (540 kg) of uranium disappeared. It was most likely transferred to the Manhattan Project’s Oak Ridge diffusion plant. The uranium oxide would have yielded approximately 7.7 pounds (3.5 kg) of U-235 after processing, around 20% of what would have been required to arm a contemporary fission weapon. One report says the fuel was used to help build the Little Boy uranium fission weapon which was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

As she was unneeded by the US Navy, U-234 was sunk off Cape Cod as a torpedo target by the USS Greenfish (SS-351) on 20 November 1947.

|

| U-234 after capture. |

|

| U-234 surrendering. Crewmen of Sutton (DE-771) in foreground with Kptlt. Johann-Heinrich Fehler (left-hand white cap). |

|

| Capt. Johann-Heinrich Fehler of the U-234. |

|

| The FuMO 61 Hohentwiel antenna was 1,400 mm wide and a height of 1,000 mm, though it had an overall width of 1, 540 mm and a height of 1,022 mm. The mesh size is approximately 15 mm. |

|

| The FuMB-26 was manufactured by the German companies Telefunken and NVK. The FuMB-26 combined the FuMB 24 and the FuMB 25. |

|

| A torpedo from USS Greenfish sinks U-234 off Cape Cod, Massachusetts. |

|

| The crew of U-234. |

|

| Lieutenant Commander Hideo Tomonaga committed suicide onboard U-234. |

|

| USS Sutton taken from U-234 — 3-inch guns trained. |

|

| Chief Gunners Mate Joe Vibert prepares to raise the American Ensign aboard U-234. LCDR Thomas Nazro, CO of USS Sutton looks on. |

|

| American Ensign flies aboard U-234. |

|

| An item is transferred from U-234 to USS Sutton. |

|

| American and German officers relax aboard U-234. |

|

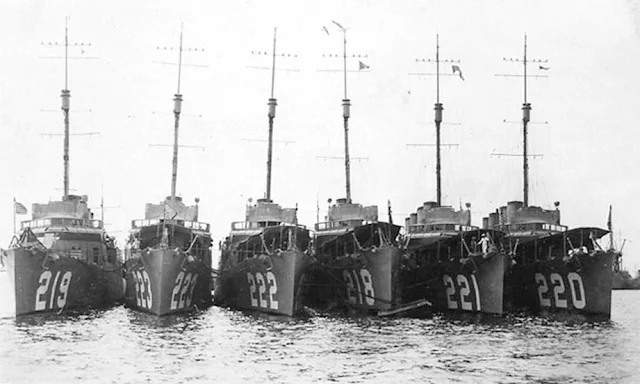

| USS Sutton, 1945. |

|

| Inspecting the U-234 at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. |