USS Laffey (DD-724) is an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer, which was constructed during World War II, laid down and launched in 1943, and commissioned in February 1944. The ship earned the nickname "The Ship That Would Not Die" for her exploits during the D-Day invasion and the Battle of Okinawa when she successfully withstood a determined assault by conventional bombers and the most unrelenting kamikaze air attack in history. Today, Laffey is a U.S. National Historic Landmark and is preserved as a museum ship at Patriots Point, outside Charleston, South Carolina.

Laffey was the second ship of the United States Navy to be named for Bartlett Laffey. Seaman Laffey was awarded the Medal of Honor for his stand against Confederate forces on 5 March 1864.

Construction and Commission

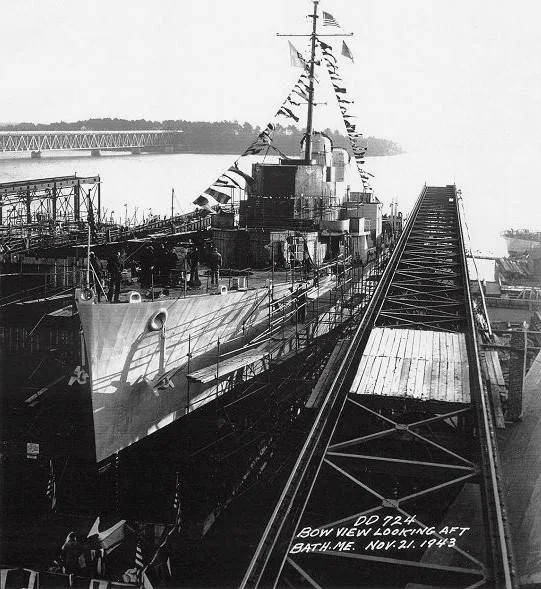

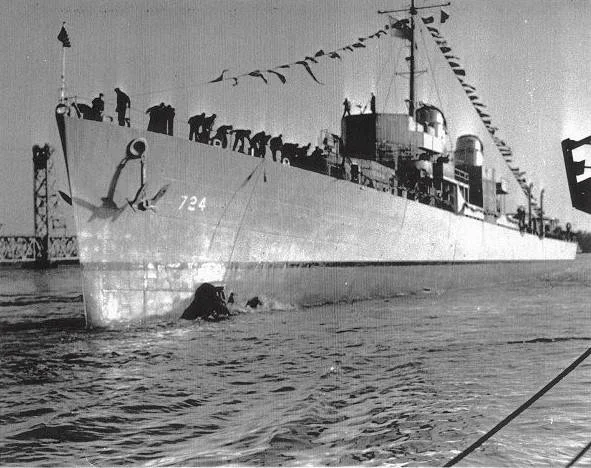

Laffey's keel was laid down on 28 June 1943 by Bath Iron Works Corp., Bath, Maine; launched on 21 November; sponsored by Ms. Beatrice F. Laffey, daughter of Seaman Laffey; and commissioned on 8 February 1944, with Commander Frederick Becton in command.

Name: Laffey

Namesake: Bartlett Laffey

Builder: Bath Iron Works

Laid down: 28 June 1943

Launched: 21 November 1943

Sponsored by: Ms. Beatrice F. Laffey

Commissioned: 8 February 1944

Decommissioned: 30 June 1947

Recommissioned: 26 January 1951

Decommissioned: 9 March 1975

Stricken: 9 March 1975

Call sign: NTHI

Hull number: DD-724

Status: Museum ship at Patriots Point, South Carolina

Class and type: Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer

Displacement: 2,200 long tons (2,235 t)

Length: 376 ft 6 in (114.76 m)

Beam: 40 ft (12 m)

Draft: 15 ft 8 in (4.78 m)

Installed power: 60,000 shp (45,000 kW)

Propulsion:

2 × steam turbines

2 × shafts

Speed: 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph)

Range: 6,500 nmi (7,500 mi; 12,000 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph)

Complement: 336

Sensors and processing systems: Radar

Armament:

6 × 5in (127mm)/38 dual purpose guns

12 × 40 mm anti-aircraft guns

11 × 20 mm anti-aircraft cannons

10 × 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes

6 × depth charge projectors

2 × depth charge tracks

Service History

World War II

Upon completion of underway training, Laffey visited Washington Navy Yard for one day and departed on 28 February 1944, arriving in Bermuda on 4 March. She returned briefly to Naval Station Norfolk, where she served as a school ship, then headed for New York City to join the screen of a convoy escort bound for England on 14 May. Refueling at Greenock, Scotland, the ship continued on to Plymouth, England, arriving on 27 May.

Laffey immediately prepared for the invasion of France. On 3 June, she headed for the Normandy beaches escorting tugs, landing craft, and two Dutch gunboats. The group arrived in the assault area, off Utah beach, Baie de la Seine, France, at dawn on D-Day, 6 June 1944. On 6–7 June, Laffey screened to seaward, and on 8–9 June, she successfully bombarded gun emplacements. Leaving the screen temporarily, Laffey raced to Plymouth to replenish and returned to the coast of Normandy the next day. On 12 June, pursuing enemy E-boats that had torpedoed the destroyer Nelson, Laffey broke up their tight formation, preventing further attacks.

Screening duties completed, Laffey returned to England, arriving at Portsmouth on 22 June, where she tied up alongside the battleship Nevada. On 25 June, she got underway with the battleship to join Bombardment Group 2 shelling the formidable defenses at Cherbourg-Octeville. Upon reaching the bombardment area, the group was taken under fire by shore batteries; destroyers Barton and O'Brien were hit. Laffey was hit above the waterline by a ricocheting shell, but it failed to explode and did little damage.

Late that day, the bombardment group retired and headed for Northern Ireland, arriving at Belfast on 1 July 1944. She sailed with Destroyer Division 119 (DesDiv 119) three days later for home, arriving at Boston on 9 July. After a month of overhaul, the destroyer got underway to test her newly installed electronic equipment. Two weeks later, Laffey set course for Norfolk, arriving on 25 August.

The next day, Laffey departed for Hawaii via the Panama Canal and San Diego, California, arriving at Pearl Harbor in September. On 23 October, after extensive training, Laffey departed for the war zone via Eniwetok, mooring at Ulithi on 5 November. The same day, she joined the screen of Task Force 38 (TF 38), then conducting airstrikes against enemy shipping, aircraft, and airfields in the Philippines. On 11 November, she spotted a parachute, left the screen, and rescued a badly wounded Japanese pilot who was transferred to the aircraft carrier Enterprise during refueling operations the next day. Laffey returned to Ulithi on 22 November, and on 27 November set course for Leyte Gulf with ships of Destroyer Squadron 60 (DesRon 60). Operating with the 7th Fleet, Laffey screened the big ships against submarine and air attacks, covered the landings at Ormoc Bay on 7 December, silenced a shore battery, and shelled enemy troop concentrations.

After a short upkeep in San Pedro Bay, Leyte on 8 December, Laffey with ships of Close Support Group 77.3 departed on 12 December for Mindoro, where she supported the landings on 15 December. After the beachhead had been established, Laffey escorted empty landing craft back to Leyte, arriving at San Pedro Bay on 17 December. Ten days later, Laffey joined Task Group 77.3 (TG 77.3) for patrol duty off Mindoro. After returning briefly to San Pedro Bay, she rejoined the 7th Fleet, and during the month of January 1945 screened amphibious ships landing troops in the Lingayen Gulf area of Luzon. Retiring to the Caroline Islands, Laffey arrived at Ulithi on 27 January. In February, she supported TF 58, conducting diversionary air strikes on Tokyo and direct air support of Marines fighting on Iwo Jima. Late in February, Laffey carried vital intelligence information to Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz at Guam, arriving on 1 March.

The next day, Laffey arrived at Ulithi for intensive training with battleships of Task Force 54 (TF 54). On 21 March, she sortied with the task force for the invasion of Okinawa. Laffey helped capture Kerama Retto, bombarded shore establishments, harassed the enemy with fire at night and screened heavy units.

Kamikaze Assault

On 15 April 1945, Laffey was assigned to radar picket station 1 about 30 mi (26 nmi; 48 km) north of Okinawa, and joined in repulsing an air attack. In total, 13 enemy aircraft were downed that day. The next day, on 16 April 1945, the Japanese launched another air attack with some 50 planes:

At 08:30, an Aichi D3A Val dive bomber appeared near the Laffey for reconnaissance. When the D3A was fired upon, it jettisoned its bomb and left. Soon after, four D3As broke formation and made a dive into Laffey. Two of the D3As came in from the starboard bow. One was shot down by the midrange 40 mm guns. The other was downed by the 20 mm guns as it got closer. The other two D3As attacked from the stern. One D3A shed pieces under fire until its fixed landing gear caught the water. The fourth D3A got close until being shot down. Immediately afterward, one of Laffey's gunners destroyed a Yokosuka D4Y making a strafing approach on the port beam. Ten seconds later, Laffey's main gun battery hit a second D4Y on a bombing approach from the starboard beam. The D4Y's bomb detonated in the water, wounding the starboard gunners with shrapnel.

At 08:42, Laffey destroyed another D3A approaching the port side. While the bomber did not completely impact the ship, it made a glancing blow against the deck before crashing into the sea, also spewing some lethal aviation fuel from its damaged engine. Three minutes later, another D3A approaching from port crashed into one of the 40 mm mounts of the ship, killing three men, destroying 20 mm guns and two 40 mm guns, and setting the magazine afire. Immediately afterward, another D3A made a strafing approach from the stern, impacted the aft 5"/38 caliber gun mount, and disintegrated as its bomb detonated the powder magazine, destroying the gun turret and causing a major fire. Another D3A making a similar approach from astern also impacted the burning gun mount after its left wing caught afire by Laffey's gunners. At about the same time, another D3A on a conventional bomb run approaching from astern dropped its bomb, jamming Laffey's rudder 26° to port and killing several men. Another D3A and another D4Y approached from port and hit Laffey.

Meanwhile, four FM-2 Wildcats took off from the escort carrier Shamrock Bay, attempting to intercept kamikazes attacking Laffey. One of the Wildcat pilots, Carl Rieman, made a dive into the kamikaze formation and targeted a D3A. His wingman took out that dive bomber while Rieman lined up behind another D3A, opened fire, and destroyed the enemy aircraft. Ten seconds later, Rieman pursued a Nakajima B5N torpedo plane, fired, and killed the Japanese pilot. Only five seconds later, Rieman lined up behind another B5N and expended the last of his ammunition. As Rieman returned to his carrier, he made diving passes at kamikazes, forcing some of them to break off their attacks. The other three Wildcats destroyed a few aircraft and then interfered with the enemy's attack runs after they exhausted their ammunition until forced to return to Shamrock Bay when their fuel ran too low to stay. Later on, a group of 12 American Vought F4U Corsair fighters of the United States Marine Corps intercepted the kamikazes. Their actions were of significant help for the Laffey.

Another D3A approached the disabled Laffey from port. A Corsair pursued the kamikaze and destroyed it after forcing it to overshoot the ship. The Corsair lined up behind a Ki-43 "Oscar" making a strafing approach on Laffey from starboard. One of Laffey's gunners hit the Oscar, causing it to crash into the ship's mast and fall into the water. The pursuing Corsair also crashed into the ship's radar antenna and fell into the water, but the pilot was later rescued by LCS-51.

Another D3A came from the stern and dropped a bomb detonating off the port side. The D3A was later destroyed by a Corsair. The Corsair quickly lined up behind another D3A and fired; but the bomb from the second D3A hit and destroyed one of Laffey's 40 mm gun mounts, killing all its gunners. The Corsair lined up behind two Oscars approaching from the bow, took out one, and was shot down by the other. The surviving Oscar was then shot down by Laffey's gunners. Laffey's main battery fired upon a D3A approaching from starboard, hitting the plane directly on the nose. The last attacker, a D4Y, was shot down by a Corsair.

Laffey survived despite being badly damaged by four bombs, six kamikaze crashes, and strafing fire that killed 32 and wounded 71. Assistant communications officer Lieutenant Frank Manson asked Captain Becton if he thought they'd have to abandon ship, to which he snapped, "No! I'll never abandon ship as long as a single gun will fire." Becton did not hear a nearby lookout softly say, "And if I can find one man to fire it."

Post-war

Laffey was then taken under tow and anchored off Okinawa on 17 April 1945. Temporary repairs were rushed and the destroyer sailed for Saipan, arriving on 27 April. Four days later, she got underway for the west coast via Eniwetok and Hawaii, arriving at Tacoma, Washington on 24 May. She entered drydock at Todd Shipyard Corp. for repair until 6 September, then sailed for San Diego, arriving on 9 September.

Two days later, Laffey got underway for exercises but collided with the submarine chaser PC-815 in a thick fog. She rescued all but one of the PC's crew before returning to San Diego for repairs.

On 5 October, she sailed for Pearl Harbor, arriving on 11 October. Laffey operated in Hawaiian waters until 21 May 1946, when she participated in Operation Crossroads, the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll, actively engaged in collecting scientific data. Radioactive decontamination of Laffey required the "sandblasting and painting of all underwater surfaces, and acid washing and partial replacement of salt-water piping and evaporators." Upon completion of decontamination, she sailed for the west coast via Pearl Harbor arriving San Diego on 22 August for operations along the west coast.

In February 1947, Laffey made a cruise to Guam and Kwajalein and returned to Pearl Harbor on 11 March. She operated in Hawaiian waters until departing for Australia on 1 May. Laffey returned to San Diego on 17 June, was decommissioned on 30 June 1947, and entered the Pacific Reserve Fleet.

Korean War

Laffey was recommissioned on 26 January 1951, with Commander Charles Holovak in command. After shakedown out of San Diego, she headed for the east coast of the US, arriving at Norfolk in February for overhaul followed by refresher training at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. In mid January 1952, she sailed for Korea, arriving in March. Laffey operated with TF 77 screening carriers Antietam and Valley Forge.

In May, with Captain Henry J. Conger in command, Laffey she took part in the blockade of Wonsan in Korea.

Although frequently subjected to hostile fire in Wonsan Harbor while embarked in his flagship, the U.S.S. LAFFEY, Captain Conger conducted a series of daring counterbattery duels with the enemy and was greatly instrumental in the success achieved by his ship. By his inspiring leadership, sound judgment and zealous devotion to duty throughout, Captain Conger contributed materially to the success of the Naval blockade of the east coast of Korea and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. — Dan A. Kimball, Secretary of the Navy

After a brief refit at Yokosuka on 30 May, Laffey returned to Korea, where she rejoined TF 77. On 22 June, she sailed for the east coast, transiting the Suez Canal and arriving Norfolk on 19 August.

Laffey operated in the Caribbean with a hunter-killer group until February 1954, departing on a world cruise which included a tour off Korea until 29 June. Laffey departed the Far East bound for the east coast via the Suez Canal arriving Norfolk on 25 August. Operating out of Norfolk, she participated in fleet exercises and plane guard duties and on 7 October rescued four passengers from Able, a schooner that had sunk in a storm off the Virginia Capes.

During the first part of 1955, Laffey participated in extensive antisubmarine exercises, visiting: Halifax, Nova Scotia; New York City; Miami; and ports in the Caribbean. In 1958, she operated with ASW carriers in Floridian and Caribbean waters.

Cold War

On 7 November 1956, Laffey departed Norfolk and headed for the Mediterranean at the height of the Suez Crisis. Upon arrival, she joined the 6th Fleet which was patrolling the Israeli-Egyptian border. When international tensions eased, Laffey returned to Norfolk on 20 February 1957, and resumed operations along the Atlantic coast. She departed on 3 September for NATO operations off Scotland. She then headed for the Mediterranean and rejoined the 6th Fleet. Laffey returned to Norfolk on 22 December. In June 1958, she made a cruise to the Caribbean for a major exercise.

Returning to Norfolk the next month, Laffey resumed regular operations until 7 August 1959, when she deployed with DesRon 32 for the Mediterranean. Laffey transited the Suez Canal on 14 December, stopped at Massawa, Eritrea, and continued on to the Aramco loading port of Ras Tanura, Saudi Arabia, where she spent Christmas. Laffey operated in the Persian Gulf until late January 1960, when she transited the Suez Canal and headed for home, arriving at Norfolk on 28 February. Laffey then operated out of Norfolk, making a Caribbean cruise. In mid-August, she participated in a large naval NATO exercise. In October, she visited Antwerp, Belgium, returning to Norfolk on 20 October, but headed back to the Mediterranean in January 1961.

While there, she assisted the British passenger and cargo ship Dara, which had suffered an explosion and was on fire. Laffey sailed for home in mid-August and arrived at Norfolk on 28 August. Laffey set out in September on a vigorous training program designed to blend the crew into an effective fighting team and continued this training until February 1963, when she assumed the duties of service ship for the Norfolk Test and Evaluation Detachment. From October 1963 to June 1964, Laffey operated with a hunter-killer group along the eastern seaboard, and on 12 June made a midshipmen cruise to the Mediterranean, arriving in Palma de Mallorca on 23 June. Two days later, the task group departed for a surveillance mission observing Soviet naval forces training in the Mediterranean. Laffey visited Mediterranean ports of Naples, Italy; Théoule, France; Rota and Valencia, Spain, returning to Norfolk on 3 September. Laffey continued to make regular Mediterranean cruises with the 6th Fleet and participated in numerous operational and training exercises in the Atlantic and Caribbean.

Laffey was decommissioned and stricken on 9 March 1975. She was the last of the Sumner class destroyers to be decommissioned.

Awards

Laffey received the Presidential Unit Citation and five battle stars for World War II service, the Korean Presidential Unit Citation and two battle stars for Korean War service, the Meritorious Unit Commendation during the Cold War, and the Battle "E" during all three conflicts.

Laffey was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986, at which time she was recognized as the only remaining US-owned Sumner-class destroyer, and for her spirited survival of the kamikaze attack.

Present Day

Laffey is currently a museum ship at Patriots Point in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, alongside another US National Historic Landmarks: the aircraft carrier Yorktown. In October 2008, it was discovered that over 100 leaks had sprung up in Laffey's hull, and officials at Patriots Point were afraid that the ship would sink at her mooring. An estimated $9 million was needed to tow the ship to dry dock for repairs, prompting Patriots Point officials to secure a $9.2 million loan from the state of South Carolina to cover the costs. On 19 August 2009, she was towed to Detyens Shipyards in North Charleston on the Cooper River for repair in drydock. The rust-eaten, corroded hull was repaired with thicker plating, miles of welding, and new paint. On 16 April 2010, the Board of Trustees of Clemson University reached a lease agreement for Patriots Point organization to moor Laffey adjacent to Clemson's property at the former Naval Base Charleston in North Charleston. Laffey was returned to Patriots Point on 25 January 2012 with more than a dozen former crew members among the crowd on hand to greet her. Said one veteran, "This means a lot of years of fighting to get her saved again. The Germans tried to sink her. The Japanese tried to sink her and then she tried to sink herself sitting here. She's whipped them all and she's back again." It cost $1.1 million to return the ship and to make repairs to accommodate her in a new berth at the front of the museum.

In Popular Culture

The ship is used in the 1984 film The Philadelphia Experiment.

In 2007, the attack on Laffey was recreated using computer graphics for the History Channel series Dogfights. The episode first aired on 13 July 2007.

In May 2018, it was officially announced that Mel Gibson would direct a major feature film about the attack on Laffey titled Destroyer.

In 2023, Laffey was added to Azur Lane in an in-game event as "Laffey II".

|

| USS Laffey (DD-724) just before commissioning day, 8 February 1944. |

|

| USS Laffey (DD 724), seen here at some time during her World War II service. |

|

| Miss Beatrice F. Laffey, daughter of Seaman Laffey, poses for a picture on launching day, 21 November 1943. |

|

| Miss Beatrice F. Laffey, daughter of Seaman Laffey, beaks the traditional bottle of champagne during the launching of the USS Laffey. |

|

| USS Laffey (DD 724) being launched on November 21, 1943 at Bath, Maine. |

|

| The Sponsor's party pose for a group photo following the launching of the USS Laffey (DD 724). |

|

| Newly launched USS Laffey (DD 724). |

|

| Commander Frederick Julian Becton, USN, first commanding officer of the USS Laffey. |

|

| USS Laffey (DD 724) in dock showing damage sustained after being hit by Japanese kamikaze off Okinawa. |

|

| USS Laffey (DD 724) underway, 26 March 1964. |

|

| USS Laffey at Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, in 2007. |

|

| Laffey's scoreboard. |

|

| USS Laffey (DD-724), 8 August 1944, location unknown. |