The Raid at Cabanatuan (Filipino: Pagsalakay sa Cabanatuan), also known as the Great Raid (Filipino: Ang Dakilang Pagsalakay), was a rescue of Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians from a Japanese camp near Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, Philippines. On January 30, 1945, during World War II, United States Army Rangers, Alamo Scouts and Filipino guerrillas attacked the camp and liberated more than 500 prisoners.

After the surrender of tens of thousands of American troops during the Battle of Bataan, many were sent to the Cabanatuan prison camp after the Bataan Death March. The Japanese shifted most of the prisoners to other areas, leaving just over 500 American and other Allied POWs and civilians in the prison. Facing brutal conditions including disease, torture, and malnourishment, the prisoners feared they would be executed by their captors before the arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and his American forces returning to Luzon. In late January 1945, a plan was developed by Sixth Army leaders and Filipino guerrillas to send a small force to rescue the prisoners. A group of over 100 Rangers and Scouts and 200 guerrillas traveled 30 miles (48 km) behind Japanese lines to reach the camp.

In a nighttime raid, under the cover of darkness and with distraction by a P-61 Black Widow night fighter, the group surprised the Japanese forces in and around the camp. Hundreds of Japanese troops were killed in the 30-minute coordinated attack; the Americans suffered minimal casualties. The Rangers, Scouts, and guerrillas escorted the POWs back to American lines. The rescue allowed the prisoners to tell of the death march and prison camp atrocities, which sparked a rush of resolve for the war against Japan. The rescuers were awarded commendations by MacArthur, and were also recognized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A memorial now sits on the site of the former camp, and the events of the raid have been depicted in several films.

Background

After the United States was attacked at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 by Japanese forces, it entered World War II to join the Allied forces in their fight against the Axis powers. American forces led by General Douglas MacArthur, already stationed in the Philippines as a deterrent against a Japanese invasion of the islands, were attacked by the Japanese hours after Pearl Harbor. On March 12, 1942, MacArthur and a few select officers, on the orders of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, left the American forces, promising to return with reinforcements. The 72,000 soldiers of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), fighting with outdated weapons, lacking supplies, and stricken with disease and malnourishment, eventually surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942.

The Japanese had initially planned for only 10,000–25,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POWs). Although they had organized two hospitals, ample food, and guards for this estimate, they were overwhelmed with over 72,000 prisoners. By the end of the 60-mile (97-km) march, only 52,000 prisoners (approximately 9,200 American and 42,800 Filipino) reached Camp O'Donnell, with an estimated 20,000 dying along the way from illness, hunger, torture, or murder. Later with the closure of Camp O'Donnell most of the imprisoned soldiers were transferred to the Cabanatuan prison camp to join the POWs from the Battle of Corregidor.

In 1944, when the United States landed on the Philippines to recapture it, orders had been sent out by the Japanese high command to kill the POWs in order to avoid them being rescued by liberating forces. One method of execution was to round the prisoners up in one location, pour gasoline over them, and then burn them alive. This was particularly apparent in light of the events of the Palawan massacre when survivors, particularly US Army Private First Class Eugene Nielson of the 59th Coast Artillery Regiment recounted the events to the US Army command after escaping to friendly lines. Because of that, the 6th Army decided to carry out a series of rescue operations behind enemy lines, raiding POW camps and rescuing American POWs before the Japanese execution orders could be carried out.

POW Camp

The Cabanatuan prison camp was named after the nearby city of 50,000 people (locals also called it Camp Pangatian, after a small nearby village). The camp had first been used as an American Department of Agriculture station and then a training camp for the Filipino army. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines, they used the camp to house American POWs. It was one of three camps in the Cabanatuan area and was designated for holding sick detainees. Occupying about 100 acres (0.40 km2), the rectangular-shaped camp was roughly 800 yards (730 m) deep by 600 yards (550 m) across, divided by a road that ran through its center. One side of the camp housed Japanese guards, while the other included bamboo barracks for the prisoners as well as a section for a hospital. Nicknamed the "Zero Ward" because zero was the probability of getting out of it alive, the hospital housed the sickliest prisoners as they waited to die from diseases such as dysentery and malaria. Eight-foot (2.4-m) high barbed wire fences surrounded the camp, in addition to multiple pillbox bunkers and four-story guard towers.

At its peak, the camp held 8,000 American soldiers (along with a small number of soldiers and civilians from other nations including the United Kingdom, Norway, and the Netherlands), making it the largest POW camp in the Philippines. This number dropped significantly as able-bodied soldiers were shipped to other areas in the Philippines, Japan, Japanese-occupied Taiwan, and Manchukuo to work in slave labor camps. As Japan had not ratified the Geneva Convention, the POWs were transported out of the camp and forced to work in factories to build Japanese weaponry, unload ships, and repair airfields.

The imprisoned soldiers received two meals a day of steamed rice, occasionally accompanied by fruit, soup, or meat. To supplement their diet, prisoners were able to smuggle food and supplies hidden in their underwear into the camp during Japanese-approved trips to Cabanatuan. To prevent extra food, jewelry, diaries, and other valuables from being confiscated, items were hidden in clothing or latrines, or were buried before scheduled inspections. Prisoners collected food using a variety of methods including stealing, bribing guards, planting gardens, and killing animals which entered the camp such as mice, snakes, ducks, and stray dogs. The Filipino underground collected thousands of quinine tablets to smuggle into the camp to treat malaria, saving hundreds of lives.

One group of Corregidor prisoners, before first entering the camp, had each hidden a piece of a radio under their clothing, to later be reassembled into a working device. When the Japanese had an American radio technician fix their radios, he stole parts. The prisoners of war thus had several radios to listen to newscasts on radio stations as far away as San Francisco, allowing the POWs to hear about the status of the war. A smuggled camera was used to document the camp's living conditions. Prisoners of war also constructed weapons and smuggled ammunition into the camp for the possibility of securing a handgun.

Multiple escape attempts were made throughout the history of the prison camp, but the majority ended in failure. In one attempt, four soldiers were recaptured by the Japanese. The guards forced all prisoners to watch as the four soldiers were beaten, forced to dig their own graves and then executed. Shortly thereafter, the guards put up signs declaring that if other escape attempts were made, ten prisoners of war would be executed for every escapee. Prisoners of war's living quarters were then divided into groups of ten, which motivated the POWs to keep a close eye on others to prevent them from making escape attempts.

The Japanese permitted the POWs to build septic systems and irrigation ditches throughout the prisoner side of the camp. An onsite commissary was available to sell items such as bananas, eggs, coffee, notebooks, and cigarettes. Recreational activities allowed for baseball, horseshoes, and ping pong matches. In addition, a 3,000-book library was allowed (much of which was provided by the Red Cross), and films were shown occasionally. A bulldog was kept by the prisoners of war, and served as a mascot for the camp. Each year around Christmas, the Japanese guards gave permission for the Red Cross to donate a small box to each of the prisoners, containing items such as corned beef, instant coffee, and tobacco. Prisoners were also able to send postcards to relatives, although they were censored by the guards.

As American forces continued to approach Luzon, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters ordered that all able-bodied POWs be transported to Japan. From the Cabanatuan camp, over 1,600 soldiers were removed in October 1944, leaving over 500 sick, weak, or disabled POWs. On January 6, 1945, all of the guards withdrew from the Cabanatuan camp, leaving the POWs alone. The guards had previously told prisoner of war leaders that they should not attempt to escape, or else they would be killed. When the guards left, the prisoners of war heeded the threat, fearing that the Japanese were waiting near the camp and would use the attempted escape as an excuse to execute them all. Instead, the prisoners went to the guards' side of the camp and ransacked the Japanese buildings for supplies and large amounts of food. Prisoners of war were alone for a couple of weeks, except when retreating Japanese forces would periodically stay in the camp. The soldiers mainly ignored the POWs, except to ask for food. Although aware of the potential consequences, the prisoners of war sent a small group outside the prison's gates to bring in two carabaos to slaughter. The meat from the animals, along with the food secured from the Japanese side of the camp, helped many of the POWs to regain their strength, weight, and stamina. In mid-January, a large group of Japanese troops entered the camp and returned the prisoners of war to their side of the camp. The prisoners of war, fueled by rumors, speculated that they would soon be executed by the Japanese.

Planning and Preparation

On October 20, 1944, General Douglas MacArthur's forces landed on Leyte, paving the way for the liberation of the Philippines. Several months later, as the Americans consolidated their forces to prepare for the main invasion of Luzon, nearly 150 Americans were executed by their Japanese captors on December 14, 1944 at the Puerto Princesa Prison Camp on the island of Palawan. An air raid warning was sounded so that the inmates would enter slit-trench and log-and-earth covered air-raid shelters, and there doused with gasoline and burned alive. One of the survivors, PFC Eugene Nielsen, recounted his tale to U.S. Army Intelligence on January 7, 1945. Two days later, MacArthur's forces landed on Luzon and began a rapid advance towards the capital, Manila.

Major Robert Lapham, the American USAFFE senior guerrilla chief, and another guerrilla leader, Captain Juan Pajota, had considered freeing the prisoners within the camp, but feared logistical issues with hiding and caring for the prisoners. An earlier plan had been proposed by Lieutenant Colonel Bernard Anderson, leader of the guerrillas near the camp. He suggested that the guerrillas would secure the prisoners, escort them 50 miles (80 km) to Debut Bay, and transport them using 30 submarines. The plan was denied approval as MacArthur feared the Japanese would catch up with the fleeing prisoners and kill them all. In addition, the Navy did not have the required submarines, especially with MacArthur's upcoming invasion of Luzon.

On January 26, 1945, Lapham traveled from his location near the prison camp to Sixth Army headquarters, 30 miles (48 km) away. He proposed to Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's intelligence chief Colonel Horton White that a rescue attempt be made to liberate the estimated 500 POWs at the Cabanatuan prison camp before the Japanese possibly killed them all. Lapham estimated Japanese forces to include 100–300 soldiers within the camp, 1,000 across the Cabu River northeast of the camp, and possibly around 5,000 within Cabanatuan. Pictures of the camp were also available, as planes had taken surveillance images as recently as January 19. White estimated that the I Corps would not reach Cabanatuan until January 31 or February 1, and that if any rescue attempt were to be made, it would have to be on January 29. White reported the details to Krueger, who gave the order for the rescue attempt.

White gathered Lt. Col. Henry Mucci, leader of the 6th Ranger Battalion, and three lieutenants from the Alamo Scouts—the special reconnaissance unit attached to his Sixth Army—for a briefing on the mission to raid Cabanatuan and rescue the POWs. The group developed a plan to rescue the prisoners. Fourteen Scouts, made up of two teams, would leave 24 hours ahead of the main force, to survey the camp. The main force would consist of 90 Rangers from C Company and 30 from F Company who would march 30 miles behind Japanese lines, surround the camp, kill the guards, and rescue and escort the prisoners back to American lines. The Americans would join up with 80 Filipino guerrillas, who would serve as guides and help in the rescue attempt. The initial plan was to attack the camp at 17:30 PST (UTC+8) on January 29.

On the evening of January 27, the Rangers studied air reconnaissance photos and listened to guerrilla intelligence on the prison camp. The two five-man teams of Alamo Scouts, led by 1st Lts. William Nellist and Thomas Rounsaville, left Guimba at 19:00 and infiltrated behind enemy lines for the long trek to attempt a reconnaissance of the prison camp. Each Scout was armed with a .45 pistol, three hand grenades, a rifle or M1 carbine, a knife, and extra ammunition.

The Rangers were armed with assorted Thompson submachine guns, BARs, M1 Garand rifles, pistols, grenades, knives, and extra ammunition, as well as a few Bazookas. Four combat photographers from a unit of the 832nd Signal Service Battalion volunteered to accompany the Scouts and Rangers to record the rescue after Mucci suggested the idea of documenting the raid. Each photographer was armed with a pistol. Surgeon Captain Jimmy Fisher and his medics each carried pistols and carbines. To maintain a link between the raiding group and Army Command, a radio outpost was established outside of Guimba. The force had two radios, but their use was only approved in requesting air support if they ran into large Japanese forces or if there were last-minute changes to the raid (as well as calling off friendly fire by American aircraft).

Behind Enemy Lines

Shortly after 05:00 on January 28, Mucci and a reinforced company of 121 Rangers under Capt. Robert Prince drove 60 miles (97 km) to Guimba, before slipping through Japanese lines at just after 14:00. Guided by Filipino guerrillas, the Rangers hiked through open grasslands to avoid enemy patrols. In villages along the Rangers' route, other guerrillas assisted in muzzling dogs and putting chickens in cages to prevent the Japanese from hearing the traveling group. At one point, the Rangers narrowly avoided a Japanese tank on the national highway by following a ravine that ran under the road.

The group reached Balincarin, a barrio (suburb) 5 miles (8.0 km) north of the camp, the following morning. Mucci linked up with Scouts Nellist and Rounsaville to go over the camp reconnaissance from the previous night. The Scouts revealed that the terrain around the camp was flat, which would leave the force exposed before the raid. Mucci also met with USAFFE guerrilla Captain Juan Pajota and his 200 men, whose intimate knowledge of enemy activity, the locals, and the terrain proved crucial. Upon learning that Mucci wanted to push through with the attack that evening, Pajota resisted, insisting that it would be suicide. He revealed that the guerrillas had been watching an estimated 1,000 Japanese soldiers camped out across the Cabu River just a few hundred yards from the prison. Pajota also confirmed reports that as many as 7,000 enemy troops were deployed around Cabanatuan located several miles away. With the invading American forces from the southwest, a Japanese division was withdrawing to the north on a road close to the camp. He recommended waiting for the division to pass so that the force would face minimal opposition. After consolidating information from Pajota and the Alamo Scouts about heavy enemy activity in the camp area, Mucci agreed to postpone the raid for 24 hours, and alerted the Sixth Army Headquarters to the development by radio. He directed the Scouts to return to the camp and gain additional intelligence, especially on the strength of the guards and the exact location of the captive soldiers. The Rangers withdrew to Platero, a barrio 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of Balincarin.

Preparation

"We couldn't rehearse this. Anything of this nature, you'd ordinarily want to practice it over and over for weeks in advance. Get more information, build models, and discuss all of the contingencies. Work out all of the kinks. We didn't have time for any of that. It was now, or not." —Capt. Prince reflecting on the time constraints on planning the raid

At 11:30 on January 30, Alamo Scouts Lt. Bill Nellist and Pvt. Rufo Vaquilar, disguised as locals, managed to gain access to an abandoned shack 300 yards (270 m) from the camp. Avoiding detection by the Japanese guards, they observed the camp from the shack and prepared a detailed report on the camp's major features, including the main gate, Japanese troop strength, the location of telephone wires, and the best attack routes. Shortly thereafter they were joined by three other Scouts, whom Nellist tasked to deliver the report to Mucci. Nellist and Vaquilar remained in the shack until the start of the raid.

Mucci had already been given Nellist's January 29 afternoon report and forwarded it to Prince, whom he entrusted to determine how to get the Rangers in and out of the compound quickly, and with as few casualties as possible. Prince developed a plan, which was then modified in light of the new report from the abandoned shack reconnaissance received at 14:30. He proposed that the Rangers would be split into two groups: about 90 Rangers of C Company, led by Prince, would attack the main camp and escort the prisoners out, while 30 Rangers of a platoon from F Company, commanded by Lt. John Murphy, would signal the start of the attack by firing into various Japanese positions at the rear of the camp at 19:30. Prince predicted that the raid would be accomplished in 30 minutes or less. Once Prince had ensured that all of the POWs were safely out of the camp, he would fire a red flare, indicating that all troops should fall back to a meetup at Pampanga River 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north of the camp where 150 guerrillas would be ready with carabao-pulled carts to transport the POWs.

One of Prince's primary concerns was the flatness of the countryside. The Japanese had kept the terrain clear of vegetation to ensure that approaching guerrilla attacks could be seen as well as to spot prisoner escapes. Prince knew his Rangers would have to crawl through a long, open field on their bellies, right under the eyes of the Japanese guards. There would only be just over an hour of full darkness, as the sun set below the horizon and the moon rose. This would still present the possibility of the Japanese guards noticing their movement, especially with a nearly full moon. If the Rangers were discovered, the only planned response was for everyone to immediately stand up and rush the camp. The Rangers were unaware that the Japanese did not have any searchlights that could be used to illuminate the perimeter. Pajota suggested that to distract the guards, a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) airplane should buzz the camp to divert the guards' eyes to the sky. Mucci agreed with the idea and a radio request was sent to command to ask for a plane to fly over the camp while the men made their way across the field. In preparation for possible injuries or wounds received during the encounter with the Japanese, the battalion surgeon, Cpt. Jimmy Fisher, developed a makeshift hospital in the Platero schoolhouse.

By dawn on January 30, the road in front of the camp was clear of traveling Japanese troops. Mucci made plans to protect the POWs once they were freed from the camp. Two groups of guerrillas of the Luzon Guerrilla Armed Forces, one under Pajota and another under Capt. Eduardo Joson, would be sent in opposite directions to hold the main road near the camp. Pajota and 200 guerrillas were to set up a roadblock next to the wooden bridge over the Cabu River. This setup, northeast of the prisoner camp, would be the first line of defense against the Japanese forces camped across the river, which would be within earshot of the assault on the camp. Joson and his 75 guerrillas, along with a Ranger Bazooka team, would set up a roadblock 800 yards (730 m) southwest of the prisoner camp to stop any Japanese forces that would arrive from Cabanatuan. Both groups would each place 25 land mines in front of their positions, and one guerrilla from each group was given a Bazooka to destroy any armored vehicles. After the POWs and the remainder of the attacking force had reached the Pampanga River meeting point, Prince would fire a second flare to indicate to the ambush sites to pull back (gradually, if they faced opposition) and head to Platero.

As the POWs had no knowledge of the upcoming assault, they went through their normal routine that night. The previous day, two Filipino boys had thrown rocks into the prisoner side of the camp with notes attached, "Be ready to go out." Assuming that the boys were pulling a prank, the POWs disregarded the notes. The POWs were becoming more wary of the Japanese guards, believing that anytime in the next few days they could be massacred for any reason. They figured that the Japanese would not want them to be rescued by advancing American forces, regain their strength, and return to fight the Japanese again. In addition, the Japanese could kill the prisoners to prevent them from telling of the atrocities of the Bataan Death March or the conditions in the camp. With the limited Japanese guard, a small group of prisoners had already decided that they would make an escape attempt at about 20:00.

Prisoner Rescue

At 17:00, a few hours after Mucci approved Prince's plan, the Rangers departed from Platero. White cloths were tied around their left arms to prevent friendly fire casualties. They crossed the Pampanga River and then, at 17:45, Prince and Murphy's men parted ways to surround the camp. Pajota, Joson, and their guerrilla forces each headed to their ambush sites. The Rangers under Prince made their way to the main gate and stopped about 700 yards (640 m) from the camp to wait for nightfall and the aircraft distraction.

Meanwhile, a P-61 Black Widow from the 547th Night Fighter Squadron, named Hard to Get, had taken off at 18:00, piloted by Capt. Kenneth Schrieber and 1st Lt. Bonnie Rucks. About 45 minutes before the attack, Schrieber cut the power to the left engine at 1,500 feet (460 m) over the camp. He restarted it, creating a loud backfire, and repeated the procedure twice more, losing altitude to 200 feet (61 m). Pretending that his plane was crippled, Schrieber headed toward low hills, clearing them by a mere 30 feet (9.1 m). To the Japanese observers, it seemed the plane had crashed and they watched, waiting for a fiery explosion. Schrieber repeated this several times while also performing various aerobatic maneuvers. The ruse continued for twenty minutes, creating a diversion for the Rangers inching their way toward the camp on their bellies. Prince later commended the pilots' actions: "The idea of an aerial decoy was a little unusual and honestly, I didn't think it would work, not in a million years. But the pilot's maneuvers were so skillful and deceptive that the diversion was complete. I don't know where we would have been without it." As the plane buzzed the camp, Lt. Carlos Tombo and his guerrillas along with a small number of Rangers cut the camp's telephone lines to prevent communication with the large force stationed in Cabanatuan.

At 19:40, the whole prison compound erupted into small arms fire when Murphy and his men fired on the guard towers and barracks. Within the first fifteen seconds, all of the camp's guard towers and pillboxes were targeted and destroyed. Sgt. Ted Richardson rushed to shoot a padlock off of the main gate using his .45 pistol. The Rangers at the main gate maneuvered to bring the guard barracks and officer quarters under fire, while the ones at the rear eliminated the enemy near the prisoners' huts and then proceeded with the evacuation. A Bazooka team from F Company ran up the main road to a tin shack which the Scouts had told Mucci held tanks. Although Japanese soldiers attempted to escape with two trucks, the team was able to destroy the trucks and then the shack.

At the beginning of the gunfire, many of the prisoners thought that it was the Japanese beginning to massacre them. One prisoner stated that the attack sounded like "whistling slugs, Roman candles, and flaming meteors sailing over our heads." Prisoners immediately hid in their shacks, latrines, and irrigation ditches.

When the Rangers yelled to the POWs to come out and be rescued, many of the POWs feared that it was the Japanese attempting to trick them into being killed. Also, a substantial number resisted because the Rangers' weapons and uniforms looked nothing like those of a few years earlier; for example, the Rangers wore caps, earlier soldiers had M1917 Helmets and coincidentally, the Japanese also wore caps. The Rangers were challenged by the POWs and asked who they were and where they were from. Rangers sometimes had to resort to physical force to remove the detainees, throwing or kicking them out. Some of the POWs weighed so little due to illness and malnourishment that several Rangers carried two men on their backs. Once out of the barracks, they were told by the Rangers to proceed to the main, or front gate. Prisoners were disoriented because the "main gate" meant the entrance to the American side of the camp.

A lone Japanese soldier was able to fire off three mortar rounds toward the main gate. Although members of F Company quickly located the soldier and killed him, several Rangers, Scouts, and POWs were wounded in the attack. Battalion surgeon Capt. James Fisher was mortally injured in the stomach and was carried to the nearby village of Balincari. Scout Alfred Alfonso had a fragment wound to his abdomen. Scout Lt. Tom Rounsaville and Ranger Pvt. 1st Class Jack Peters were also wounded by the barrage.

A few seconds after Pajota and his men heard Murphy fire the first shot, they fired on the alerted Japanese contingent situated across the Cabu River. Pajota had earlier sent a demolitions expert to set charges on the unguarded bridge to go off at 19:45. The bomb detonated at the designated time, and although it did not destroy the bridge, it formed a large hole over which tanks and other vehicles could not pass. Waves of Japanese troops rushed the bridge, but the V-shaped choke point created by the Filipino guerrillas repulsed each attack. One guerrilla, who had been trained to use the Bazooka only a few hours earlier by the Rangers, destroyed or disabled four tanks that were hiding behind a clump of trees. A group of Japanese soldiers made an effort to flank the ambush position by crossing the river away from the bridge, but the guerrillas spotted and eliminated them.

At 20:15, the camp was secured from the Japanese and Prince fired his flare to signal the end of the assault. No gunfire had occurred for the last fifteen minutes. However, as the Rangers headed towards the meetup, Cpl. Roy Sweezy was shot twice by friendly fire, and later died. The Rangers and the weary, frail, and disease-ridden POWs made their way to the appointed Pampanga River rendezvous, where a caravan of 26 carabao carts waited to transport them to Platero, driven by local villagers organized by Pajota. At 20:40, once Prince determined that everyone had crossed the Pampanga River, he fired his second flare to indicate to Pajota and Joson's men to withdraw. The Scouts stayed behind at the meetup to survey the area for enemy retaliatory movements. Meanwhile, Pajota's men continued to resist the attacking enemy until they could finally withdraw at 22:00, when the Japanese forces stopped charging the bridge. Joson and his men met no opposition, and they returned to help escort the POWs.

Although the combat photographers were able to shoot images of the trek to and from the camp, they were unable to use their cameras during the night-time raid, as the flashes would indicate their positions to the Japanese. One of the photographers reflected on the nighttime hindrance: "We felt like an eager soldier who had carried his rifle for long distances into one of the war's most crucial battles, then never got a chance to fire it." The Signal Corps photographers instead assisted with escorting the POWs out of the camp.

Trek to American Lines

"I made the Death March from Bataan, so I can certainly make this one!" —one of the POWs during the trek back to American lines

By 22:00, the Rangers and ex-POWs arrived at Platero, where they rested for half an hour. A radio message was sent and received by Sixth Army at 23:00 that the mission had been a success, and that they were returning with the rescued prisoners to American lines. After a headcount, it was discovered that POW Edwin Rose, a deaf British soldier, was missing. Mucci dictated that none of the Rangers could be spared to search for him, so he sent several guerrillas to do so in the morning. It was later learned that Rose had fallen asleep in the latrine before the attack. Rose woke early the next morning, and realized the other prisoners were gone and that he was left behind. Nevertheless, he took the time to shave and put on his best clothes that he had been saving for the day he would be rescued. He walked out of the prison camp, thinking that he would soon be found and led to freedom. Sure enough, Rose was found by passing guerrillas. Arrangements were made for a tank destroyer unit to pick him up and transport him to a hospital.

In a makeshift hospital at Platero, Scout Alfonso and Ranger Fisher were quickly put into surgery. The fragment was removed from Alfonso's abdomen, and he was expected to recover if returned to American lines. Fisher's fragment was also removed, but with limited supplies and widespread damage to both his stomach and intestines, it was decided more extensive surgery would need to be completed in an American hospital.

As the group left Platero at 22:30 to trek back towards American lines, Pajota and his guerrillas continually sought out local villagers to provide additional carabao carts to transport the weakened prisoners. The majority of the prisoners had little or no clothing and shoes, and it became increasingly difficult for them to walk. When the group reached Balincarin, they had accumulated nearly 50 carts. Despite the convenience of using the carts, the carabao traveled at a sluggish pace, only 2 miles per hour (3.2 km/h), which greatly reduced the speed of the return trip. By the time the group reached American lines, 106 carts were being used.

In addition to the tired former prisoners and civilians, the majority of the Rangers had only slept for five to six hours over the past three days. The soldiers frequently had hallucinations or fell asleep as they marched. Benzedrine was distributed by the medics to keep the Rangers active during the long march. One Ranger commented on the effect of the drug: "It felt like your eyes were popped open. You couldn't have closed them if you wanted to. One pill was all I ever took—it was all I ever needed."

P-61 Black Widows again helped the group by patrolling the path they took on its way back to American lines. At 21:00, one of the aircraft destroyed five Japanese trucks and a tank located on a road 14 miles (23 km) from Platero that the group would later travel on. The group was also met by circling P-51 Mustangs that guarded them as they neared American lines. The freed prisoner George Steiner stated that they were "jubilant over the appearance of our airplanes, and the sound of their strafing was music to our ears".

During one leg of the return trip, the men were stopped by the Hukbalahap, Filipino Communist guerrillas who hated both the Americans and the Japanese. They were also rivals to Pajota's men. One of Pajota's lieutenants conferred with the Hukbalahap and returned to tell Mucci that they were not allowed to pass through the village. Angered by the message, Mucci sent the lieutenant back to insist that pursuing Japanese forces would be coming. The lieutenant came back and told Mucci that only Americans could pass, and Pajota's men had to stay. Both the Rangers and guerrillas were finally allowed through after an agitated Mucci told the lieutenant that he would call in an artillery barrage and level the whole village. In fact, Mucci's radio was not working at that point.

At 08:00 on January 31, Mucci's radioman was able to finally contact Sixth Army headquarters. Mucci was directed to go to Talavera, a town captured by the Sixth Army 11 miles (18 km) from Mucci's current position. At Talavera, the freed soldiers and civilians boarded trucks and ambulances for the last leg of their journey home. The POWs were deloused, and given hot showers and new clothes. At the POW hospital, one of the Rangers was reunited with his rescued father, who had been assumed killed in combat three years earlier. The Scouts and the remaining POWs who had stayed behind to get James Fisher onto a plane also encountered resistance by the Hukbalahap. After threatening the communist band, the Scouts and POWs were granted safe passage and reached Talavera on February 1.

A few days after the raid, Sixth Army troops inspected the camp. They collected a large number of death certificates and cemetery layouts, as well as diaries, poems, and sketchbooks. The American soldiers also paid 5 pesos to each of the carabao cart drivers who had helped to evacuate the POWs.

Outcome and Historical Significance

The raid was considered successful—489 POWs were liberated, along with 33 civilians. The total included 492 Americans, 23 British, three Dutch, two Norwegians, one Canadian, and one Filipino. The rescue, along with the liberation of Camp O'Donnell the same day, allowed the prisoners to tell of the Bataan and Corregidor atrocities, which sparked a new wave of resolve for the war against Japan.

Prince gave a great deal of credit for the success of the raid to others: "Any success we had was due not only to our efforts but to the Alamo Scouts and Air Force. The pilots (Capt. Kenneth R. Schrieber and Lt. Bonnie B. Rucks) of the plane that flew so low over the camp were incredibly brave men."

Some of the Rangers and Scouts went on bond drive tours around the United States and also met with President Roosevelt. In 1948, the United States Congress created legislation which provided $1 ($12.68 today) for each day the POWs had been held in a prisoner camp, including Cabanatuan. Two years later, Congress again approved an additional $1.50 per day (a combined total of $31.66 in 1994 terms).

Estimates of the Japanese soldiers killed during the assault ranged from 530 to 1,000. The estimates include the 73 guards and approximately 150 traveling Japanese who stayed in the camp that night, as well as those killed by Pajota's men attempting to cross the Cabu River.

Several Americans died during and after the raid. A prisoner weakened by illness died of a heart attack as a Ranger carried him from the barracks to the main gate. The Ranger later recalled, "The excitement had been too much for him, I guess. It was really sad. He was only a hundred feet from the freedom he had not known for nearly three years." Another prisoner died of illness just as the group had reached Talavera. Although Mucci had ordered that an airstrip be built in a field next to Platero so that a plane could evacuate Fisher to get medical attention, it was never dispatched, and he died the next day. His last words were "Good luck on the way out." The other Ranger killed during the raid was Sweezy, who was struck in the back by two rounds from friendly fire. Both Fisher and Sweezy are buried at Manila National Cemetery. Twenty of Pajota's guerrillas were injured, as were two Scouts and two Rangers.

The American prisoners were quickly returned to the United States, most by plane. Those who were still sick or weakened remained at American hospitals to continue to recuperate. On February 11, 1945, 280 POWs left Leyte aboard the transport USS General A.E. Anderson bound for San Francisco via Hollandia, New Guinea. In an effort to counter the improved American morale, Japanese propaganda radio announcers broadcast to American soldiers that submarines, ships, and planes were hunting the General Anderson. The threats proved to be a bluff, and the ship safely arrived in San Francisco Bay on March 8, 1945.

News of the rescue was released to the public on February 2. The feat was celebrated by MacArthur's soldiers, Allied correspondents, and the American public, as the raid had touched an emotional chord among Americans concerned about the fate of the defenders of Bataan and Corregidor. Family members of the POWs were contacted by telegram to inform them of the rescue. News of the raid was broadcast on numerous radio outlets and newspaper front pages. The Rangers and POWs were interviewed to describe the conditions of the camp, as well as the events of the raid. The enthusiasm over the raid was later overshadowed by other Pacific events, including the Battle for Iwo Jima and the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The raid was soon followed by additional successful raids, such as the raid of Santo Tomas Civilian Internment Camp on February 3, the raid of Bilibid Prison on February 4, and the raid at Los Baños on February 23.

A Sixth Army report indicated that the raid demonstrated " ... what patrols can accomplish in enemy territory by following the basic principles of scouting and patrolling, 'sneaking and peeping,' [the] use of concealment, reconnaissance of routes from photographs and maps prior to the actual operation, ... and the coordination of all arms in the accomplishment of a mission." MacArthur spoke about his reaction to the raid: "No incident of the campaign in the Pacific has given me such satisfaction as the release of the POWs at Cabanatuan. The mission was brilliantly successful." He presented awards to the soldiers who participated in the raid on March 3, 1945. Although Mucci was nominated for the Medal of Honor, he and Prince both received Distinguished Service Crosses. Mucci was promoted to colonel and was given command of the 1st Regiment of the 6th Infantry Division. All other American officers and selected enlisted received Silver Stars. The remaining American enlisted men and the Filipino guerrilla officers were awarded Bronze Stars. Nellist, Rounsaville, and the other twelve Scouts received Presidential Unit Citations.

In late 1945, the bodies of the American troops who died at the camp were exhumed, and the men moved to other cemeteries. Land was donated in the late 1990s by the Filipino government to create a memorial. The site of the Cabanatuan camp is now a park that includes a memorial wall listing the 2,656 American prisoners who died there. The memorial was financed by former American POWs and veterans, and is maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission. A joint resolution by Congress and President Ronald Reagan designated April 12, 1982 as "American Salute to Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Memorial Day". In Cabanatuan, a hospital is named for guerrilla leader Eduardo Joson.

|

Prisoners Rescued |

|

|

American soldiers |

464 |

|

British soldiers |

22 |

|

Dutch soldiers |

3 |

|

American civilians |

28 |

|

Norwegian civilians |

2 |

|

British civilian |

1 |

|

Canadian civilian |

1 |

|

Filipino civilian |

1 |

|

Total |

522 |

Depictions in Film

Several films have focused on the raid, while also including archival footage of the POWs. Edward Dmytryk's 1945 film Back to Bataan, starring John Wayne, opens by retelling the story of the raid on the Cabanatuan POW camp—with real life film of the POW survivors. In July 2003, the PBS documentary program American Experience aired an hour-long film about the raid, titled Bataan Rescue. Based on the books The Great Raid on Cabanatuan and Ghost Soldiers, the 2005 John Dahl film The Great Raid focused on the raid intertwined with a love story. Prince served as a consultant on the film, and believed it depicted the raid accurately. Marty Katz conveyed his interest in producing the film: "This [rescue] was a massive operation that had very little chance of success. It's like a Hollywood movie—it couldn't really happen, but it did. That was why we were attracted to the material." Another cover of the raid aired in December 2006 as an episode of the documentary series Shootout!.

References

Alexander, Larry (2009). Shadows in the Jungle: The Alamo Scouts Behind Japanese Lines in World War II. Penguin Group.

Bilek, Tony; O'Connell, Gene (2003). No Uncle Sam: The Forgotten of Bataan. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press.

Black, Robert W. (1992). Rangers in World War II. Random House.

Breuer, William B. (1994). The Great Raid on Cabanatuan. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Carson, Andrew D. (1997). My Time in Hell: Memoir of an American Soldier Imprisoned by the Japanese in World War II. McFarland & Company.

Hogan, David W. (1992). Raiders or Elite Infantry?: The Changing Role of the U.S. Army Rangers from Dieppe to Grenada. ABC-CLIO.

Hunt, Ray C. (1986). Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerrilla in the Philippines. University Press of Kentucky.

Johnson, Forrest Bryant (2002). Hour of Redemption: The Heroic WWII Saga of America's Most Daring POW Rescue. Warner Books.

Kelly, Arthur L. (1997). BattleFire!: Combat Stories from World War II. University Press of Kentucky.

Kerr, E. Bartlett (1985). Surrender & Survival: The Experience of American POWs in the Pacific 1941–1945. William Morrow and Company.

King, Michael J. (1985). Rangers: Selected Combat Operations in World War II. DIANE Publishing.

McRaven, William H. (1995). Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare Theory and Practice. New York: Presidio Press.

Norman, Michael; Norman, Elizabeth M. (2009). Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

O'Donnell, Patrick K. (2003). Into the Rising Sun: In Their Own Words, World War II's Pacific Veterans Reveal the Heart of Combat. Simon & Schuster.

Parkinson, James W.; Benson, Lee (2006). Soldier Slaves: Abandoned by the White House, Courts, and Congress. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Rottman, Gordon (2009). The Cabanatuan Prison Raid – The Philippines 1945. Osprey Publishing; Osprey Raid Series #3.

Sides, Hampton (2001). Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Epic Story of World War II's Most Dramatic Mission. New York: Doubleday.

Waterford, Van (1994). Prisoners of the Japanese in World War II. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company.

Wodnik, Bob (2003). Captured Honor. Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press.

Wright, John M. (2009). Captured on Corregidor: Diary of an American P.O.W. in World War II. McFarland & Company.

Zedric, Lance Q. (1995). Silent Warriors of World War II: The Alamo Scouts Behind Japanese Lines. Ventura, California: Pathfinder Publishing of California.

|

| A former POW's drawing of one prisoner giving a drink to another at the Cabanatuan camp. |

|

| A hut used to house prisoners in the camp. |

|

| Capt. Juan Pajota, January 1945. |

|

| Lt.Col. Henry Mucci, Army Ranger. [US Army Signal Corps] |

| |

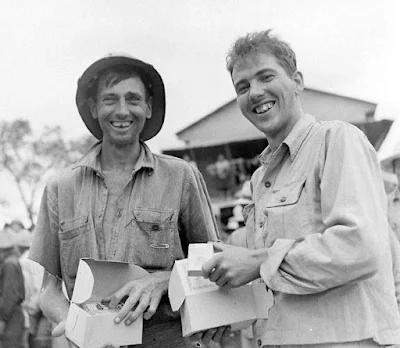

| Ranger Captain James Fisher, M.D. (left) with Captain Bob Prince a few hours before the raid on Cabanatuan. Fisher died of wounds on the way back to Allied lines. Jan 30, 1945. [US Army] |

|

| Captain Pajota's guerrillas at Cabanatuan. |

|

| Illustration of the layout of the camp and the positions of the attacking American forces. |

|

| Map of the routes taken by the US Rangers in their Raid at Cabanatuan. Different routes were used for the infiltration and extraction behind Japanese lines. |

|

| Former Cabanatuan POWs at a makeshift hospital in Talavera. |

|

| Robert Prince, Army Ranger. |

|

| Bird's eye view illustration of the actions taken by the US Rangers in their Raid at Cabanatuan. |

|

| Map of the routes taken by the US Rangers in their Raid at Cabanatuan. |

|

| Men of the U.S. Army’s 6th Ranger Battalion, accompanied by Alamo Scouts, cross a river bed on the way to the Cabanatuan prison camp. |

|

| Inside the camp at Cabanatuan, a prisoner walks past huts in this undated photo. |

|

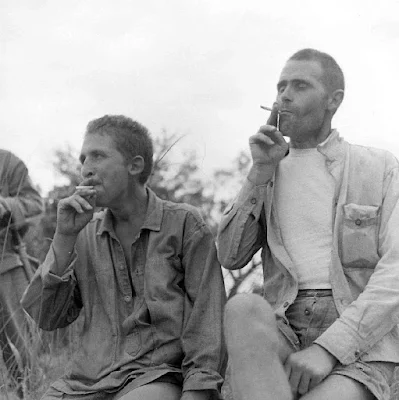

| Former prisoners of the Japanese at Cabanatuan enjoy their first moments of freedom in many months while several of their exhausted liberators lie asleep on the ground following the raid. |

|

| Rangers and Filipino guerrillas at the camp after the raid. |

|

| Ranger Capt. Robert Prince with one of the Filipino guerrillas that supported the raid. |

|

| Rangers that participated in the Raid. |

|

| A member of the 6th US Army Special Reconnaissance Force holding a Browning Automatic Rifle talks with with a Filipino guerrilla. [National Archives] |

|

| The raiders slog along paths cut through the fields of tall grass that covered much of this part of Luzon. [National Archives] |

|

| Unlike this growth, the grass closer to the prison camp was kept cut short, which would make surprising the Japanese guards tricky. [National Archives] |

|

| As soon as possible after the raid, rangers and prisoners were treated for wounds and other medical problems. [National Archives] |

|

| Prisoners and wounded too ill or weak to walk were transported in carts pulled by water buffalo. [National Archives] |

|

| Raiders on the trek to the camp. |

|

| Filipino guerrillas. |

|

| Ten Rangers and two Alamo Scouts from the Cabanatuan Raid met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Oval Office of the White House, 7 March 1945. |