|

| British Airborne Lifeboat Mk III. |

Airborne lifeboats were powered lifeboats that were made to be dropped by fixed-wing aircraft into water to aid in air-sea rescue operations. An airborne lifeboat was to be carried by a heavy bomber specially modified to handle the external load of the lifeboat. The airborne lifeboat was intended to be dropped by parachute to land within reach of the survivors of an accident on the ocean, specifically airmen survivors of an emergency water landing. Airborne lifeboats were used during World War II by the United Kingdom and on Dumbo rescue missions by the United States from 1943 until the mid-1950s.

Development

Air-sea rescue by flying boat or floatplane was a method used by various nations before World War II to pick up aviators or sailors who were struggling in the water. Training and weather accidents could require an aircrew to be pulled from the water, and these two types of seaplane were occasionally used for that purpose. The limitation was that if the water's surface were too rough, the aircraft would not be able to land. Though closer to shore (e.g. in the English Channel) the RAF Air Sea Rescue Service operated High Speed Launches but until 1943, the most that could be done was to drop emergency supplies to the survivors, including an inflatable rubber dinghy carried as-standard in RAF aircraft.

The airborne lifeboat was developed to provide downed airmen with a more navigable and seaworthy vessel that could be sailed greater distances than the rubber dinghy. One of the reasons necessitating this was that when ditching or abandoning an aircraft near enemy-held territory, often the tides and winds would propel the rubber dinghy toward shore, despite the efforts of the occupants to paddle away, resulting in their eventual capture.

British Lifeboats

Uffa Fox

The first air-dropped lifeboat was British, a 32-foot (10 m) wooden canoe-shaped boat designed in 1943 by Uffa Fox to be dropped by Royal Air Force (RAF) Vickers Warwick heavy bombers for the rescue of aircrew downed in the Channel. The lifeboat was dropped from a height of 700 feet (210 m), and its descent to the water was slowed by six parachutes. It was balanced so that it would right itself if it overturned—all subsequent airborne lifeboats were given this feature. When it hit the water the parachutes were jettisoned and rockets launched 300 ft (90 m) lifelines. Coamings were inflated on the descent to give it self-righting.

Fox's airborne lifeboat weighed 1,700 pounds (770 kg) and included two 4-horsepower (3 kW) motors—sufficient to make about 6 knots (11 km/h)–augmented by a mast and sails along with an instruction book to teach aircrew the rudiments of sailing. The lifeboats were first carried by Lockheed Hudson aircraft in February 1943. Later, Vickers Warwick bombers carried the Mark II lifeboat. The Fox boats successfully saved downed aircrew as well as glider infantrymen dropped in the water during Operation Market-Garden.

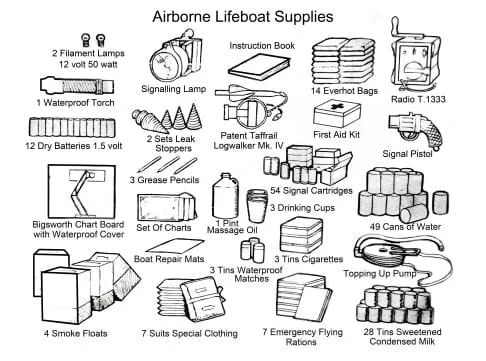

The lifeboats carried emergency equipment, a radio, waterproof suits, rations and medical supplies.

February 1943 saw the first of RAF Davidstow Moor's Air Sea Rescue [ASR] operations with the arrival of a detachment from 279 Squadron RAF. The Squadron was formed on 16 November 1941 at Bircham Newton and carried out trials and test drops of the new rigid airborne lifeboat designed by Uffa Fox. The lifeboat was a fully equipped vessel powered by two 4hp two stroke engines. It carried emergency rations, warm survival suits, drinking water, chocolate, first aid kits, distress signals, paddles, fluorescene, telescopic mast, a sail, balers, plugs to stop leaks, a signal whistle and a radio transmitter. This was a great improvement on the earlier Lindholme dinghy as it enabled the downed aircrew to make their own way back by the use of on board motors and sails. If they ran out of fuel they could make sail.

These Mk1 lifeboats were 22ft 6ins long and weighed 1700lbs. Six parachutes opened automatically on release from the aircraft. As the boat settled in the water all sorts of devices came into action. The sea water set up a chemical reaction which sent out a drogue from the bow and held the boat into wind. Two lines, each 300ft long, were ejected at opposite angles of 45 degrees to the boats heading. At each end of the line was a drogue which automatically inflated and floated. Exhausted or injured men could grab the lines and gradually pull themselves aboard. The parachutes were released from the boat and drifted away.

Equipped with Hudson aircraft 279 became the first squadron to carry the airborne lifeboat operationally. They operated over the Bay of Biscay and the Western Approaches from April 1942 to December 1943. The squadron carried the code OS during it's detachment at Davidstow.

Hudson OS S/279, with the first airborne lifeboat to be carried operationally, flew from RAF Davidstow Moor on 17 February 1943.

Saunders-Roe

In early 1953, Saunders-Roe at Anglesey completed the Mark 3 airborne lifeboat to be fitted underneath the Avro Shackleton maritime reconnaissance aircraft. The Mark 3 was made entirely of aluminum unlike the Fox Mark 1 which was made of wood. Dropped from a height of 700 feet (210 m), the Mark 3 descended under four 42-foot (13 m) parachutes at a rate of 20 feet (6 m) per second into the rescue zone. As the lifeboat dropped, pressurized bottles of carbon dioxide inflated the self-righting chambers at the bow and stern. Upon touching the water, the parachutes were released to blow away, and a drogue opened to slow the boat's drift and aid in the survivors reaching the lifeboat. At the same time, two rockets fired, one to each side, sending out floating lines to provide easier access to the lifeboat for ditched airmen. Doors that opened from the outside provided access to the interior, and the flat deck was made to be self-draining. The craft was powered by a Vincent Motorcycles HRD T5 15-horsepower (11 kW) engine with enough fuel to give a range of 1,250 miles (2,010 km). Sails and a fishing kit were provided, as well as an awning and screen to protect against sun and sea spray. The Mark 3 measured 31 feet (9 m) from bow to stern and 7 feet (2 m) across the beam and held enough to supply 10 people with food and water for 14 days. It carried protective suits, inflatable pillows, sleeping bags, and a first-aid kit.

American Lifeboats

Higgins A-1 Lifeboat

The A-1 lifeboat was a powered lifeboat that was made to be dropped by fixed-wing aircraft into water to aid in air-sea rescue operations. The sturdy airborne lifeboat was to be carried by a heavy bomber specially modified to handle the external load of the lifeboat. The A-1 lifeboat was intended to be dropped by parachute during Dumbo missions to land within reach of the survivors of an accident on the ocean, specifically airmen survivors of an emergency water landing.

Design

The first airborne lifeboat was designed in the United Kingdom by Uffa Fox in 1943 and used from February 1943. In the United States, Andrew Higgins evaluated the Fox boat and found it too weak to survive mishap in emergency operations. In November 1943, Higgins assigned engineers from his company to make a sturdier version with two air-cooled engines. Higgins Industries, known for making landing craft (LCVP) and PT boats, produced the A-1 lifeboat, a 3,300-pound (1,500 kg), 27-foot (8 m) airborne lifeboat made of laminated mahogany with 20 waterproof internal compartments so that it would not sink if swamped or overturned. Intended to be dropped by modified Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, it was ready for production in early 1944.

The yellow-painted vessel was supplied with enough food, water and clothing for 12 survivors to last for about 20 days in the ocean. It was provided with sails kept relatively small so that inexpert operators could use them. A "Gibson Girl" survival radio was aboard with an antenna to be lifted up with a kite. Its two engines propelled the boat at 8 miles per hour (13 km/h); if just one were used the speed was 5 miles per hour (8 km/h). The effective cruising range was about 1,500 miles (2,400 km) with some 100 to 150 miles (160 to 240 km) made per day.

Higgins also produced a smaller 18-foot (5.5 m) version of the A-1 for the US Coast Guard that could be dropped by PBY Catalinas. This version was half the weight of the A-1. Unlike the larger version for the USAAF, the smaller Higgins air dropped lifeboat was designed to rescue only eight or fewer persons. While a November 1945 Popular Mechanics article states it was in USCG service there are few public references to this smaller version of the A-1.

Operations

The Higgins A-1 lifeboat was to be dropped by an SB-17 traveling at an airspeed of 120 miles per hour (190 km/h) and an altitude of about 1,500 feet (500 m). Precisely as the aircraft passed directly over the rescue target the boat was to be released. The boat dropped free for a short distance, then static lines attached to the aircraft's bomb bay catwalk drew taut, pulling out three 48-foot (15 m) parachutes of a standard U.S. Army design. Under the open parachutes, the boat took on a 50° bow-downward angle and descended at a rate of 27 feet per second (8 m/s), or about 18 miles per hour (29 km/h). In a manner similar to Fox's airborne lifeboat, upon contact with seawater, rocket-projected lines were automatically sent out 200 yards (180 m) to each side to make it easier for survivors to reach the Higgins lifeboat. The parachutes settled into the water to create a sea anchor holding the boat steady while survivors worked to reach it. Inside the boat, the crew of the aircraft that dropped the lifeboat would have placed a map giving the approximate position of the boat and a recommended compass setting to take in order to facilitate rescue.

The first Higgins airborne lifeboat used in an emergency was dropped on March 31, 1945, in the North Sea, some 8 miles (13 km) offshore of the Dutch island of Schiermonnikoog. In the evening of March 30, a PBY Catalina landed in six-foot (2 m) swells to save the pilot of a downed P-51 Mustang, but one of the Catalina's engines lost its oil in the process, rendering the flying boat unable to take off. Darkness, distance, and poor visibility prevented the Catalina men from making contact with the Mustang pilot who drifted in a raft and was eventually taken prisoner of war. The next morning, a Vickers Warwick located the Catalina and dropped a Fox-designed airborne lifeboat nearby, but after being retrieved the lifeboat began to break up from repeatedly smashing against the Catalina in the increasingly heavy seas.

Instead, the six aircrew lashed three of their own inflatable rubber dinghies together and abandoned the aircraft in ten-foot (3 m) swells. Another Warwick dropped another Fox airborne lifeboat some distance away, but its parachute didn't open and it was destroyed upon striking the water. An SB-17 flying in the 35-mile-per-hour (56 km/h), 40 °F (4 °C) breeze dropped its load—Higgins Airborne Lifeboat No. 25—from an altitude of 1,200 feet (370 m) to land about 100 feet (30 m) from the men. As it hit the water, one of the lifeboat's tethering rocket lines snaked out over the junction of two of the dinghies, making an ideal shot. The six airmen transferred to the Higgins lifeboat where they huddled down and waited for three days in the worst North Sea storm of 1945 before two more Fox airborne boats were dropped with gasoline and supplies on April 3, the lifeboats either swamping or breaking up upon hitting the water. On April 4 in continuing rough seas, the airmen were picked up by two Rescue Motor Launch (RML) boats, and the Higgins A-1 lifeboat, unable to be towed, was intentionally sunk by gunfire.

In the last eight months of World War II, Dumbo operations complemented simultaneous United States Army Air Forces heavy bombing operations against Japanese targets. On any one large-scale bombing mission carried out by Boeing B-29 Superfortresses, at least three submarines were posted along the air route, and Dumbo aircraft sent to patrol the distant waters where they searched the water's surface and listened for emergency radio transmissions from distressed aircraft. At the final bombing mission on August 14, 1945, 9 land-based Dumbos and 21 flying boats covered a surface and sub-surface force of 14 submarines and 5 rescue ships.

Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) operated Dumbo flights along the West Coast in the early 1950s, using the PB-1G, a B-17 variant. Such a flight is depicted briefly in the 1954 film The High and the Mighty. Further Dumbo flights were conducted jointly by the USCG and the U.S. Navy during the Korean War.

The A-1 lifeboat was joined and then succeeded by the A-3 lifeboat from 1947. The A-3 lifeboat was used until the mid-1950s, after which winch equipped helicopters had become commonplace enough to be used to lift survivors instead of dropping a lifeboat to them.

EDO Corporation A-3 Lifeboat

The A-3 lifeboat was an airborne lifeboat developed by the EDO Corporation in 1947 for the United States Air Force (USAF) as a successor to the Higgins Industries A-1 lifeboat. The A-3 lifeboat was a key element of "Dumbo" rescue flights of the 1950s.

Specifications

EDO built the lifeboat of aluminum alloy to be carried by the SB-29 Super Dumbo performing air-sea rescue duties during the Korean War. Approximately 100 of these lifeboats were built—their serial numbers began at 501 and continued in sequence.

The A-3 lifeboat was 30.05 feet (9.16 m) long and it weighed 2,736 pounds (1,241 kg) when fully loaded and ready for attachment to the aircraft. The A-3 lifeboat could rescue 15 people. It was powered by a four-cylinder four-stroke Meteor 20 gasoline engine made by the Red Wing Motor Company. With an Ailsa Craig propeller it was expected to give a speed of 8 knots (9.2 mph) under calm water conditions. Nearly 100 US gallons (380 L) of fuel were on board. The airborne lifeboat was dropped from the SB-29 on a single 100-foot (30 m) parachute. Like previous airborne lifeboat designs, it was self-righting. The boat had a boarding ladder, and carried food and water for the rescued people.

In March 1951, Time magazine reported that the USAF was testing a radio controlled steering device for the A-3 lifeboat. After the boat dropped into the sea, a radio operator aboard the rescue aircraft would start the lifeboat's engine remotely, then direct the boat toward the survivors to make it easier for them to reach. After climbing aboard, the survivors could talk to the circling aircraft by two-way radio. A gyrocompass aboard the lifeboat would be set toward the nearest safe land, and the supply of fuel would allow for 800 miles (1,300 km) of range, with further range possible if additional water, food and fuel supplies were dropped along the way. The USAF expected all their A-3 lifeboats to be equipped with radio control by early 1952.

World War II and Korean War

After World War II, sixteen Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers were converted to carry the lifeboat and assigned rescue duty on a rotating basis, designated SB-29 in a role called "Super Dumbo". The first SB-29s were received by the Air Rescue Service in February 1947. They served in the Korean War where A-3 lifeboats were carried by Super Dumbos over the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan.

From the beginning of the Korean War, the A-3 lifeboat was kept shackled underneath an SB-29 waiting in constant readiness on the ground at each rescue airbase. Inside of the aircraft, however rainwater could enter the boat and pool within an open end of the deployment parachute's bag. After one air drop which failed because of water that had frozen at high altitude, trapping the parachute, the A-3 lifeboat was stored disconnected from the aircraft and with a rain cover in place.

Later in the Korean War, the USAF worked on improving the A-3 with a butterfly fin to stabilize the boat till the parachute opened, a full cover, enabling the drop aircraft to start the lifeboat's motor and steer it to the location of persons in the water, and other improvements. Whether any of these improved A-3s were built beyond the prototype and saw active use is unknown.

Survivors

Lifeboat number 603 has been restored by the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Lifeboat SN Unknown is displayed at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.

Douglas Aircraft Radio Controlled Life Raft

The airborne life boats used by the USAF at the start of the 1950s had two major flaws; they required specially modified aircraft to drop them, and in heavy weather and high winds when dropped they could drift away from the exhausted survivors or be swamped and over turned. The USAF, "Air Sea Rescue Unit of the Air Material Command", was tasked with studying the problem and coming up with a solution. Their solution was an air dropped life boat which before it inflated in the water, looked like a torpedo and could be carried by almost any aircraft in service that had heavy wing pylons. When the boat was dropped near the survivors, on impacting the water large inflatable tubes which were connected to the rescue torpedo inflated, resulting in a radio controlled self-propelled life raft. The pilot would then start the life raft engine by radio control and steer the life raft to the survivors. When the survivors had boarded the life raft one of the rescue aircraft circling above would continue to control and steer the life raft to a safe zone for pick up, or allow the survivors to take over control. The life raft contained its own autopilot, water, dehydrated food, a two way rescue radio and enough fuel for 300 miles of travel.

Bibliography

Crocker, Mel. Black Cats and Dumbos: WW II's Fighting PBYs. Crocker Media Expressions, 2002.

Hardwick, Jack; Ed Schnepf. The Making of the Great Aviation Films. General Aviation Series, Volume 2. Challenge Publications, 1989.

Hearst Magazines (May 1952). "Lifeboat Has Invisible Crew". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. pp. 110–111.

Lloyd, Alwyn T. B-17 Flying Fortress in Detail and Scale, Volume 11: Derivatives, part 2. Fallbrook, California: Aero Publishers, 1983.

Marion, Forrest L. "Bombers and boats: SB-17 and SB-29 combat operations in Korea." Air Power History, Volume 51, Spring 2004.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II: The struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943. University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War. Naval Institute Press, 2007.

Ostrom, Thomas P. The United States Coast Guard, 1790 to the present: a history. Elderberry Press, Inc., 2004.

Strahan, Jerry E. Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II. LSU Press, 1998.

|

| A rigged Airborne Lifeboat in front of the Vickers Warwick B.1, BV351, sometime after June 6th, 1944. |

_(IWM_A_29338).jpg) |

| A Vickers Warwick drops an airborne life boat, c. 1944-45. (Imperial War Museum A29338) |

|

| A Vickers Warwick bomber carrying the Uffa Fox-designed airborne lifeboat underneath. |

|

| Boeing SB-17G, an air-sea rescue aircraft modified to carry the A-1 lifeboat, of the 5th Rescue Squadron, Flight D, c. 1950. (U.S. Air Force) |

|

| Boeing SB-17G "Ready Teddy," Morotai Island, 1945 (Courtesy of the City of Coffs Harbour, Accession Number mus07-8837). |

|

| Rear view of an EDO A-3 lifeboat, S/N 603, on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. (George Campbell, 2018) |

|

| Front view of an EDO A-3 lifeboat, S/N 603, on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. (George Campbell, 2018) |

|

| The lifeboat held by three parachutes, dropping from the Fairey Barracuda. (Imperial War Museum A29660) |

.jpg) |

| The lifeboat held by three parachutes, dropping from the Fairey Barracuda. (Imperial War Museum A29661) |

|

| "Ditched air crew" in dinghy paddle towards the lifeboat as it touches down. (Imperial War Museum A29662) |

.jpg) |

| The lifeboat and parachutes in the sea. (Imperial War Museum A29663) |

|

| "Air crew" clambering into the lifeboat. (Imperial War Museum A29664) |

.jpg) |

| The "air crew" safely in the lifeboat. (Imperial War Museum A29665) |

|

| The "air crew" got the lifeboat underway with gib and mainsail set. (Imperial War Museum A29666) |

.jpg) |

| Model of a Airborne Lifeboat MkI (or MkIA). Wood and metal model, L: 50in W: 11in H: 44in (rigged) Weight: 40kg incl case Scale: 1/6. (Imperial War Museum MOD 122) |

|

| Vickers Warwick ASR Mark I, BV356 ‘HK-E’, of No. 269 Squadron releasing Airborne Lifeboat. |

|

| Vickers Warwick ASR Mark I, BV356 ‘HK-E’, of No. 269 Squadron dropping Airborne Lifeboat. |

|

| Airborne Lifeboat released from Vickers Warwick ASR Mark I, BV356 ‘HK-E’, of No. 269 Squadron floating down beneath parachutes. |

|

| Airborne Lifeboat dropped by Vickers Warwick ASR Mark I, BV356 ‘HK-E’, of No. 269 Squadron lands in water. |

|

| Groundcrew of No. 269 Squadron RAF wheel a Mark II Lifeboat to its parent aircraft, Vickers Warwick ASR Mark I, BV508 'HK-B', at Lagens. (Imperial War Museum CA125) |

|

| Uffa Fox’s airborne lifeboat at the Classic Boat Museum, Newport. |

|

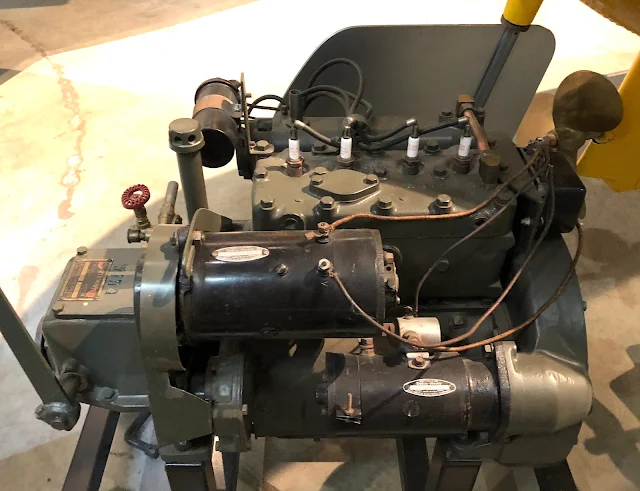

| Airborne lifeboat at the Museum of the Broads. Notice the unusual Saildrive engine it used on a stand in front, and also the Norfolk punt on display beneath. |

|

| Poster showing lifeboat equipment. |

|

| Release of the lifeboat. Here, the lifeboat has just been released and the pilot chute is being pulled out by the static line. (U.S. Air Force) |

|

| Another view of the airborne lifeboat on display in the Museum of the [Norfolk and Suffolk] Broads. |

|

| A U.S. Coast Guard Boeing PB-1G Flying Fortress search and rescue plane in flight. The USCG used 18 former USAAF SB-17G from 1945 to 1959. |

|

| Boeing PB-1G, US Coast Guard. |

|

| U.S. Coast Guard PB-1G stationed at Kodiak, Alaska, c. 1947. |

|

| Boeing/Douglas B-17H-DL (s/n 44-83719) taxis at Hayward Airport, California, April 20, 1947. |

|

| The Sikorsky R-5 and Boeing B-17H from the Air Rescue Service Squadron at Hamilton Field arriving at Hayward Airport on April 20, 1947 for an open house exhibit. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment