|

| USS Bennington underway off Long Island, September 25, 1944. She is painted in camouflage Measure 32, Design 17A (#1). |

USS Bennington (CV/CVA/CVS-20) was one of 24 Essex-class

aircraft carriers built during World War II for the United States Navy. The

ship was the second US Navy ship to bear the name, and was named for the

Revolutionary War Battle of Bennington (Vermont). Bennington was commissioned

in August 1944, and served in several of the later campaigns in the Pacific

Theater of Operations, earning three battle stars. Decommissioned shortly after

the end of the war, she was modernized and recommissioned in the early 1950s as

an attack carrier (CVA), and then eventually became an Antisubmarine Aircraft

Carrier (CVS). In her second career, she spent most of her time in the Pacific,

earning five battle stars for action during the Vietnam War. She served as the

recovery ship for the Apollo 4 space mission.

She was decommissioned in 1970, and sold to be scrapped in

India in 1994.

The ship was laid down on 15 December 1942 by the New York

Navy Yard, and launched on 28 February 1944, sponsored by Mrs. Melvin J. Maas,

wife of Congressman Maas of Minnesota. Bennington was commissioned on 6 August

1944, with Captain J. B. Sykes in command.

On 15 December, Bennington got underway from New York and

transited the Panama Canal on the 21st. The carrier arrived at Pearl Harbor on

8 January 1945 and then proceeded to Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands, where she

joined Task Group 58.1 on 8 February. Operating out of Ulithi, she took part in

the strikes against the Japanese home islands (16 – 17 February and 25

February), Volcano Islands (18 February – 4 March), Okinawa (1 March), and the

raids in support of the Okinawa campaign (18 March – 11 June). On 7 April,

Bennington's planes participated in the attacks on the Japanese task force

moving through the East China Sea toward Okinawa, which resulted in the sinking

of the battleship Yamato, light cruiser Yahagi, and four destroyers. On 5 June,

the carrier was damaged by a typhoon off Okinawa and retired to Leyte for

repairs, arriving on 12 June. Her repairs completed, Bennington left Leyte on 1

July, and from 10 July – 15 August took part in the aerial raids on the

Japanese home islands.

She continued operations in the western Pacific, supporting

the occupation of Japan until 21 October. On 2 September, her planes

participated in the mass flight over Missouri and Tokyo during the surrender

ceremonies. Bennington arrived at San Francisco on 7 November, and early in

March 1946 transited the Panama Canal en route to Norfolk, Virginia. Following

pre-inactivation overhaul, she went out of commission in reserve at Norfolk on

8 November 1946.

The carrier began modernization at New York Naval Shipyard on

30 October 1950 and was recommissioned as CVA-20 on 13 November 1952. In this

period, Bennington was the recipient of over 11 million man-hours during her

SCB-27A conversion. Her deck was extended 43 ft (13 m) in length and was

widened by 8 ft (2.4 m). The point was to modernize the ship to be able to

launch jet aircraft. She also had the 5 in (130 mm) guns removed from the

flight deck, which were replaced by smaller 3 in (76 mm) guns.

On 13 November, Captain David. B. Young took command of

Bennington in a ceremony attended by more than 1,400, including the Secretary

of the Navy Dan A. Kimball and Rear Admiral Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter who said

the Bennington was "the most modern carrier in our fleet today."

Marine Air Group 14 (MAG-14), under the command of Colonel

W.R. Campbell, USMC reported for duty on Bennington on 13 February 1953, and

Bennington set off for the waters off Florida to conduct carrier

qualifications. The first trap was made on Bennington since her recommissioning

by Lieutenant Colonel T.W. Furlow in his AD Skyraider. Furlow was the

commanding officer of Marine Attack Squadron 211 (VMA-211). The first jet

aircraft to land on Bennington occurred on 18 February by Major Carl E. Schmitt

in an F9F-5 Cougar. When the qualifications were over, Bennington headed for

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base where she underwent 11 weeks of shakedown training.

Her shakedown lasted until May 1953, when she returned to

Norfolk for final fleet preparations. On 27 April, a downcomer tube in Boiler

Room One slipped loose which caused an explosion that killed 11 men, and

seriously wounded four others. From 14 May 1953 – 27 May 1954, she operated

along the eastern seaboard; made a midshipman cruise to Halifax, Nova Scotia;

and a cruise in the Mediterranean.

At 06:11 on 26 May 1954, while cruising off Narragansett Bay,

the fluid in one of her catapults leaked out and was detonated by the flames of

a jet causing the forward part of the flight deck to explode, setting off a

series of secondary explosions which killed 103 crewmen, predominantly among

the senior NCO's of the crew and injured 201 others. Bennington proceeded under

her own power to Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island, to land her

injured. This tragedy caused the Navy to switch from hydraulic catapults to

steam catapults for launching aircraft. A monument to the sailors who died in

this tragic event was erected near the southwest corner of Fort Adams State

Park in Newport, Rhode Island.

Moving to New York Naval Shipyard for repairs, she was

completely rebuilt from 12 June 1954 – 19 March 1955. On 22 April, the

Secretary of the Navy came aboard and presented medals and letters of

commendation to 178 of her crew in recognition of their heroism on 26 May 1954.

As of 1 August 1955, she was part of Carrier Division 2, along with Lake

Champlain. Bennington returned to operations with the United States Atlantic

Fleet (including a two-month shake-down cruise to Guantanamo Bay with ATG-201)

until departing Mayport, Florida for the Pacific on 8 September. She steamed by

way of Cape Horn and arrived at San Diego one month later. The carrier then

served with the Pacific Fleet making two Far Eastern cruises.

The 1955–56 air wing was Air Task Group 201, composed of VF-13,

flying F9F-6, VA-36 (The US Navy's first operational light jet Attack Squadron)

flying F9F-5; VA-105. flying AD-6, VC (later VFAW)4, flying F2H3, VC (Later

VAAW)33, flying AD-5N. This deployment represented the Fleet evaluation of the

combination of the angled deck and the mirror landing system, which reduced the

US Navy's Carrier Landing Accident rate by 75%. During 1956 the ship was

administratively part of Carrier Division Five, though operationally directed

at times by Carrier Division One.

The 1956–57 air wing consisted of one squadron each of the

following: FJ3 Fury, F2H Banshee, F9F Cougar fighters, AD-6 Skyraider, AD-5N

Skyraider, and AD-5W attack aircraft, AJ2 Savage bombers, and F9F-8P photo

reconnaissance planes.

On 7 May 1957, while docked in Sydney for Coral Sea Day

celebrations, ten University of Sydney students dressed as pirates boarded the

aircraft carrier in the early morning hours undetected. While some began

soliciting donations from the Navy crew for a local charity, others entered the

bridge. The public address system was turned on. "Now hear this!"

announced Paul Lennon, a medical student. "The U.S.S. Bennington has been

captured by Sydney University pirates!" Alarms for general quarters,

atomic and chemical attacks were sounded, rousing the crew from their bunks.

Marines escorted the students off the ship. No charges were filed.

She was redesignated as an ASW support carrier CVS-20 on 30

June 1959, and was on hand for the 1960 Laotian Crisis. She also had three

tours of duty – between 1965 and 1968 – in the Vietnam War.

As an ASW carrier, her air wing consisted of two squadrons of

S-2F Trackers, a squadron of Sikorsky SH-34s ASW helicopters which were

replaced in 1964 by SH-3A Sea Kings in that role. Airborne early warning was

first provided by EA-1Es modified for the AEW role, these were upgraded in 1965

to the E-1 Tracer which is built on the same frame as the S-2 Tracker. In

1964–1965, a detachment of A-4B Skyhawks were also embarked.

On 18 May 1966, while cruising off of San Diego, California,

Bennington hosted the experimental LTV XC-142A as it executed 44 short takeoffs

and landings and six vertical takeoffs and landings, the ship steaming at

various speeds to generate different velocities of wind-over-the-deck.

She was the prime recovery vessel for the unmanned Apollo 4

mission and on 9 November 1967 recovered the spacecraft which had splashed down

10 mi (16 km) from the ship.

Bennington was decommissioned on 15 January 1970, stricken on

20 September 1989, and sold for scrap on 12 January 1994, being subsequently

towed across the Pacific for scrapping in India.

The 1949 film Sands of Iwo Jima shows footage of the USS

Bennington using a short hydraulic catapult to launch propeller-driven Corsair

fighters.

Jerry Clower served two years aboard the USS Bennington 1945

and 1946. Clower was a popular country comedian best known for his stories of

the rural South and nicknamed "The Mouth of Mississippi".

The 1955 film The Blue and Gold has actual footage of flight

deck operations including jet and helicopter take-offs. One take-off shows a

wing fold up on take-off and subsequent crash off the bow.

Name: USS Bennington

Namesake: Battle of Bennington, 1777

Ordered: 15 December 1941

Builder: New York Naval Shipyard

Laid down: 15 December 1942

Launched: 28 February 1944

Commissioned: 6 August 1944

Decommissioned: 8 November 1946

Recommissioned: 13 November 1952

Decommissioned: 15 January 1970

Reclassified:

CV to CVA 1 October 1952

CVA to CVS 30 June 1959

Struck: 20 September 1989

Fate: Scrapped in 1994

Class and type: Essex-class aircraft carrier

Displacement:

As built:

27,100 tons standard

36,380 tons full load

Length:

As built:

820 feet (250 m) waterline

872 feet (266 m) overall

Beam:

As built:

93 feet (28 m) waterline

147 feet 6 inches (45 m) overall

Draft:

As built:

28 feet 5 inches (8.66 m) light

34 feet 2 inches (10.41 m) full load

Propulsion:

As designed:

8 × boilers 565 psi (3,900 kPa) 850 °F (450 °C)

4 × Westinghouse geared steam turbines

4 × shafts

150,000 shp (110 MW)

Speed: 33 knots (61 km/h)

Range: 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h)

Complement: As built 2,600 officers and enlisted

Armament:

As built:

4 × twin 5 inch (127 mm) 38 caliber guns

4 × single 5 inch (127 mm) 38 caliber guns

8 × quadruple 40 mm 56 caliber guns

46 × single 20 mm 78 caliber guns

Armor:

As built:

2.5 to 4 inch (60 to 100 mm) belt

1.5 inch (40 mm) hangar and protective decks

4 inch (100 mm) bulkheads

1.5 inch (40 mm) STS top and sides of pilot house

2.5 inch (60 mm) top of steering gear

Aircraft carried:

As built:

90–100 aircraft

1 × deck-edge elevator

2 × centerline elevators

|

| The future USS Bennington (CV-20) being prepared for launching in a building dock at the New York Navy Yard, 23 February 1944. She was christened three days later. (Naval History & Heritage Command NH 75631) |

|

| The future USS Bennington (CV-20) being floated out of drydock at the New York Navy Yard, Saturday, 26 February 1944, following her christening by Mrs. Melvin J. Maas (née Katherine Endress), wife of Melvin Joseph Maas, US Representative from Minnesota (R) and Colonel, USMCR. Bennington was the first of the Essex-class carriers to be built in the New York Navy Yard and it was also the first carrier to be built in a dry-dock. |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20), World War II. Overhead plan and starboard profile meticulously drawn by John Robert Barrett. |

|

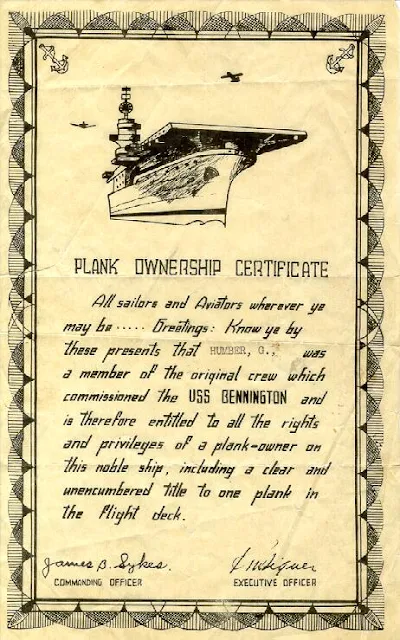

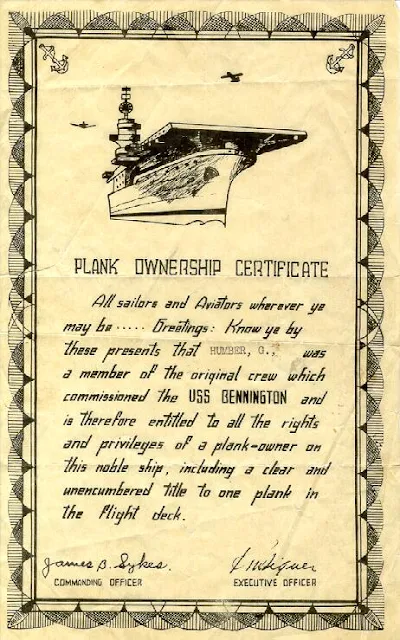

| Plank owner certificate for George Humber Sr. |

|

| USS Bennington underway off Long Island, September 25, 1944. She is painted in camouflage Measure 32, Design 17A (#1). |

|

| Doing workups with her air group, October 1944. Note her lightly colored, unstained flight deck. |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) photographed from a plane that has just taken off from her flight deck, during the ship's shakedown period, 20 October 1944. (Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives photo # 80-G-289645) |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) underway during her shakedown, 20 October 1944, en route to Trinidad, British West Indies. She is painted in camouflage Measure 32, Design 17a (#1). Note tanker in the left distance. (Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command (NH&HC) NH 97579) |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) underway during her shakedown period, October–November 1944. |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) underway during her shakedown period, October–November 1944. |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) underway during her shakedown period, October–November 1944. |

|

| Bennington painted in Design 17A (#2), 13 December 1944, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard before going into combat. Compare her new, three-color camouflage (Design 17A(#2)) to her previous six-color scheme Design 17A (#1)). Light conditions make colors appear to be lighter than they actually were (see below). Bennington was one of the Essex-class ships not fitted with additional AA 40-mm mounts on the starboard side, amidships. |

|

| As above. This photo does show her flight deck stained blue, with dull black numerals and dash lines. Note there are no elevator outlines. The inside screens of the lift shaft are painted black. Note that the 5"/38 single mounts and some of the 40-mm quads were at times surrounded by rails instead of splinter shields, in order to save weight, but this was a temporary measure. (National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) photo 80-G-298091) |

|

| As above. USS Bennington (CV-20) en route from New York Navy Yard Annex to Naval Anchorage, Gravesend Bay. Photograph was taken by Naval Air Station, New York. The vertical colors are Navy Blue (5-N), Ocean Gray (5-O) and Haze Gray (5-H), with the horizontal surfaces Deck Blue (20-B). The panels of haze gray appear to be lightened to Pale Gray (5-P), but are probably reflecting the bright sun at this angle. (National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) photo 80-G-298091) |

|

| As above. Bow view at 700 feet. (US Navy photo, now in the collections of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 80-G-298089) |

|

| As above. Vertical aerial view at 1,200 feet. (US Navy photo, now in the collections of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 80-G-298094) |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) ferrying aircraft to Pearl Harbor on her maiden voyage to fight in World War II, January 1945. |

|

| Bennington tied up at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor Hawaii with her entire air group (CVG-82) on the flight deck, January 1945. (National Archives photo) |

|

| Deck crewmen aboard USS Bennington (CV-20) maneuver an SB2C Helldiver of Bombing Squadron (VB) 82 into position on the carrier's flight deck. VB-82 operated from Bennington during the period February–June 1945. (Navy and Marine Corps Museum photo 1996.253.357) |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) seen from USS Sigsbee (DD-502) in Task Group 58.1, 14 February–13 April 1945. (Photo by LT(JG) Gordon Barrett) |

|

| USS Bennington conducting air ops and alongside for UNREP with USS Harrison (DD-573) watch standers. Task Group 58.1, February–May 1945. (Photo by CTM Tom McCann) |

|

| USS Bennington conducting air ops and alongside for UNREP with USS Harrison (DD-573) watch standers. Task Group 58.1, February–May 1945. (Photo by CTM Tom McCann) |

|

| TBM-3 Avenger from VT-82 deck-launching from Bennington in a rain squall, February 1945. (Photo now in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, #80-G-305181) |

|

| VT-82 TBM-3 Avenger #101 makes a gear-up landing on 16 February 1945, after receiving battle damage during a raid over Tokyo, Japan. The plane was so badly damaged that it was pushed overboard; one of eleven lost that day. Note the empty drop tanks on the port catwalk ready for re-arming and re-fueling of the air group for the next strike. (US Navy Photo, now in the custody of the US National Archives at College Park, Maryland 80-G-305176) |

|

The background story to the damage to this Grumman TBM Avenger is quite fascinating:

On February 18, 1945, the fast carriers returned to Chichi Jima, 150 miles north of Iwo Jima. Bob King flew an Avenger torpedo bomber off the USS Bennington, with Jimmy Dye and Grady York as his radioman and gunner. Chichi Jima, with its half-moon bay presented a difficult target for the flyboys and it was their first mission. Only one of them would return.

Chichi Jima's bay was surrounded on three sides by rugged hills. It was a uniquely dangerous place to dive as the antiaircraft fire came not only from below but also from all sides as the planes dove below the level of the hilltops. As the planes pulled out and escaped to the west, Japanese fire would actually come down at them from the caves above.

Bob Cosbie was flying an Avenger to the right of King's bomber, and Jesse Naul was flying behind Cosbie's plane. The three planes were to bomb Chichi Jima's small airstrip. Many years later, Naul would tell James Bradley what happened:

"We came in at about nine thousand feet and we were getting ready to go into our dive. I was behind Cosbie's plane. Suddenly, antiaircraft fire shot Cosbie's right wing off. His plane went into a clockwise spin, spinning clockwise down toward the right, where his wing had been.

"Cosbie's plane flipped upside down and went sideways. It slammed into King's plane. Cosbie's left wing hit King's plane between the turret and the vertical stabilizer. At the same time, Cosbie's propeller hit King's left wing and chewed off four feet of it.

"King's plane then went into a spin. King thought they would crash, so he told his crew to bail out. Jimmy and Grady bailed out. My crew yelled, 'We see two chutes.'

"King had his seat belt off, fixing to bail out, and to his surprise, he got the plane straight. He 'caught it,' meaning he caught the spin and righted the plane. He kept flying."

Cosbie's Avenger continued its violent spin, and the crew couldn't get out. Gunner Lou Gerig and radi-oman Gil Reynolds went down with their pilot. Naul speculated on what their final minutes might have been like:

"Cosbie went into his spin at nine to ten thousand [feet]. His plane just spun and spun. Let's say they were all alive when the plane went into that spin. Even though they were healthy American males, the centrifugal force would have pinned them to the walls and they wouldn't have been able to get out.

"If they were conscious, they knew what was happening and were fighting to get out. They'd be trying to unhook their seat belts and pop the doors off, but they wouldn't have been able to get out of their seats.

"When a loaded seventeen-thousand-pound plane is spinning, it creates a lot of force. It's like a saucer at an amusement park that is spinning and pinning you back. It's the same thing. The force of the spin would force them to remain in the position they were in when they started going down. Finally, they smacked into the water and that was it."

Dye and York parachuted down in the midst of the exploding shells. "Their chutes were surrounded by antiaircraft bursts," recalled Joe Bonn. "I dismissed them as shot up, dead." But the two flyboys were alive, and they landed safely just off shore.

"We flew down to drop them a life raft," Ralph Sengewalt said, "But we didn't drop because we could see Jimmy and Grady in knee-deep water, walking toward the shore. We thought they'd be prisoners and they'd be safe — at least that was our hope."

Meanwhile, King was nursing his damaged Avenger back to his carrier. He was accompanied by other planes from the squadron. All who saw the torpedo bomber still airborne with most of its left wing missing were amazed. But there was more. The fuselage between the turret and the tail was bent where Cosbie's wing had hit. "Like a playing card bent in half," said Naul. "It was bent in the middle and drooped."

"We told him his landing gear wouldn't work, that he shouldn't even try," Naul said. "We told him he'd have to make a water landing." King ditched his plane near the fleet, and the bomber bent with the im-pact.

"I tossed King a life raft," said Robert Akerblom. "I opened the door, holding it. 'Now' my pilot yelled."

After his bad jolt, King spent the night in sick bay, but he was alive. He was also a changed man.

"King was the most heartbroken man I ever saw in my life," Sengewalt told Bradley. "He lost two men and lived. He didn't say much. I think he never really recovered from that flight, he was so moved. We knew what he went through; no one blamed him. What he did was almost miraculous."

"All he'd say was, 'I had my seat belt off,'" remembered Naul. "Everybody would have done the same thing. King gave Jimmy and Grady an opportunity to get out. He was looking out for his guys like he was supposed to. He was ready to bail when the plane righted. He was surprised when it did. He had his seat belt off, ready to jump."

Jimmy Dye and Grady York would be one of the eight flyboys captured and killed by the Japanese on Chichi Jima.

Source: Flyboys by James Bradley (Little, Brown: Boston, 2003) pgs. 291-301

—via J.C. Falkenberg III on Reddit at r/WWIIplanes

Here are a few notes on the damage in the photo:

Look at the right aileron — the degree of visible deflection shows how much stick movement the pilot is applying to counter the uneven lift from the loss of the outer part of the left wing. That’s about 30-40% of total aileron movement.

It’s amazing that the pilot has any roll control at all considering the damage to the left wing. The Avenger used hydraulics for the folding wings, bomb bay doors, flaps, and landing gear, but used standard manually operated cables for the flight controls. Damage as seen in this picture often fouled the cables and prevented any control of the aircraft. That’s part of what makes the spin recovery so incredible.

You can tell the pilot has released his straps. Otherwise he couldn’t lean that far forward. The shoulder straps allow very limited movement of the upper body to prevent the pilot from slamming his head into the dash/instrument panel during a trap (carrier landing) or other sudden deceleration.

You can see the glare reflecting off the greenhouse glass on the left side of the aircraft, but there’s no glare from the rear ball gun turret. Why? It’s because the kick-out panel for the turret gunner is on the left side of the aircraft. It’s held in with a few quick release twist handles but can also be knocked out with a hard shove or kick. We know that the turret gunner has already bailed out, so the panel has been knocked out so he could exit the plane.

The radioman/belly gunner exited from a hatch on the opposite side of the fuselage. The hatch is easily entered from the ground and the gunner climbs up to his position after entering the aircraft from the side hatch. The radioman would then enter through the hatch as well. The pilot climbs in over the left wing and thought the sliding canopy, which is close to fully opened in this photo. There is no direct access from the pilot to the rear positions. The radioman would go out the side hatch in an aerial bailout.

The Avenger was notoriously hard to evacuate in water landings. The pilot could get out through the canopy, and the turret gunner had the kick-out panel he could go through, but the radioman had to climb up through the turret and follow the turret gunner out the side panel. That means the radioman has to unbelt and then climb through the turret — not an easy task to begin with, and made even worse if he’s injured. To top it off, the glass bombardier panel at the rear of the bomb bay would often break or get loosened in its mounting, letting water in faster and filling the radioman’s space quickly.

That glass panel allowed the Avenger to be equipped with a Norden Bombsight for level bombing. The radioman would act as the bombardier.

Looking at the aft and of the aircraft, the dorsal fin in front of the vertical tail plane has been crushed over from the impact of the other aircraft. The amazing part is that the empennage appears to be un-damaged. It also looks like the fuselage has been crushed to slightly out of its normal elliptical shape at the top. It must’ve been a hell of an impact and credit goes to Grumman for a robust design and to GM for building it properly.

—Via Quibblicous on Reddit at r/WWIIplanes

(Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| Probably the ultimate "Murderers' Row" photo with 10 Essex-class carriers plus the Enterprise in the anchorage. It must also have been taken on the 13th March 1945 shortly after the arrival of Task Group 12.2. The Randolph in berth #27 had been hit two days previously whilst at anchor by a long range kamikaze strike. The repair ship USS Jason (AR-8) is visible alongside (unknown source). |

|

| Key to previous photo: Ulithi Anchorage looking north: Berth #5: USS South Dakota (BB-57), #6 USS Massachusetts (BB-59), #8 USS Bunker Hill (CV-17), #101 USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), #27 USS Randolph (CV-15) and USS Jason (AR-8), #28 USS Hornet (CV-12), #29 USS Wasp (CV-18), #30 USS Bennington (CV-20), #26 USS Essex (CV-9), #25 USS Intrepid (CV-11), #24 USS Enterprise (CV-6), #23 USS Yorktown (CV-10), #22 USS Hancock (CV-19), #21 USS Franklin (CV-13). (All positions correlate with war logs of each ship and the mooring plan.) |

|

| One of Bennington's VMF-123's F4U-1D's after flipping, the pilot had a back injury. (Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| An F4U Corsair from one of the Marine Squadrons serving on Bennington in April 1945 (VMF-112 and VMF-123). Looks like it had its wingtip shot up. (Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| An F4U Corsair (VMF-112 or VMF-123) that missed the arresting wires, April 1945. (Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| F4U Corsair, deck launch. (Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| Lowell Love crawled out on the forward antenna mast in the down position to get this picture of the forecastle, bow and 40mm gun tub. |

|

| Aboard USS Bennington (CV-20), ARM1C R.J. Bell carries .30-cal ammunition for SB2C Helldiver aircraft. Photographed by PHoM3 W.R. Davis, released April 1945. (Official US Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 80-G-322447) |

|

| Japanese plane exploding from anti-aircraft fire while off Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands, 16 April 1945. US Navy ships shown are USS Bennington (CV-20) and USS Massachusetts (BB-59). Photographed from USS Hornet (CV-12). (Official US Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 80-G-331610) |

|

| USS McKee (DD-575) operating at sea in the Ryukyus area with Task Force 58, 26 April 1945. USS Bennington (CV-20) is in the left background. (Official U.S. Navy photograph, from the collections of the Naval History & Heritage Command NH 103701) |

|

| Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat fighters prepare for takeoff from the aircraft carrier USS Bennington (CV-20) circa May 1945. (Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 80-G-K-4946) |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) refueling from USS Chicopee (AO-34), 12 May 1945, in Task Group 58.1. (National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), photo # 80-G-338791) |

|

| Kamikaze plane (upper right) explodes in mid-air near the aircraft carrier USS Bennington (CV-20) in a photo taken from the deck of her sister carrier USS Hornet (CV‑12), 14 May 1945, while operating in an area approximately 80–100 miles southeast of southern Kyushu. (National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) photo, # 80-G-331621) |

|

| Looking towards the bow from the bridge during the typhoon of June 1945. This storm smashed both the Hornet and Bennington's flight deck down around their bows. (Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| On 5 June 1945 USS Bennington was damaged by a typhoon off Okinawa and retired to Leyte for repairs, arriving 11 June. Her repairs completed, the carrier left Leyte 1 July 1945 and during 10 July-15 August took part in the final raids on the Japanese home islands. |

|

| As above. |

|

| As above. |

|

| As above. |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20) at Leyte, Philippine Islands, in June 1945. Her flight deck is being repaired from typhoon damage suffered off Okinawa on 5 June 1945. (Naval History and Heritage Command UA 539.11) |

|

| Bennington recovering SB2C-5's off the coast of Japan, late July 1945. (Photo by Lowell Love) |

|

| Lowell Love (standing, far left) and some of the Bennington's photographers getting briefed for a combat mission over Japan, July 1945. |

|

| Prisoner of War Camp near Kamiyama town in the hills of Honshu, Japan. Planes from USS Bennington (CV-20) discovered this camp and the next day, instead of dropping their usual load of destruction, dropped packages to the prisoners. The prisoners' expression of gratitude can be seen by TNX—a telegraphic form of "thanks" in the yard of the camp. Photograph received 12 September 1945. (National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) photo 80-G-338541) |

|

| USS Bennington (CV-20), CINCPAC photo #496020, also BuAer photo with the same number. Taken at Pearl Harbor, released 23 January 1946. |

|

| Aerial view of Pearl Harbor, circa 16–23 January 1946. Ships present are: USS Bennington (CV-20) moored across the channel at NAS Ford Island; USS Cape Gloucester (CVE-109), opposite Bennington; USS Troilus (AKA-46), moored astern of Cape Gloucester; USS LST-1078, moored astern of USS LST-1070; USS Terror (CM-5); USS LST-459 with LCT-1015 secured to her main deck, astern of USS LST-863. Moored forward of LST-863 are two unidentified minesweepers and three larger, unidentified ships. The next pier has two unidentified ships, possibly AKs; the survey ship USS Sumner (AGS-5); and two unidentified minesweepers. USS LST-737 moored astern of USS LST-45, moored astern of numerous minesweepers. And possibly USS Shipley Bay (CVE-85). (Official US Navy photo, file number 496019, from CINCPAC, released 23 January 1946. Also stamped BUAer, 496019) |

|

| USS Bennington (CVA-20) passes the wreck of USS Arizona (BB-39) in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Memorial Day, 31 May 1958. Bennington's crew is in formation on the flight deck, spelling out a tribute to the Arizona's crewmen who were lost in the 7 December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Note the outline of Arizona's hull and the flow of oil from her fuel tanks. (Official U.S. Navy Photo USN 1036055) |

|

| One of the USS Bennington's officers inscribes a bomb "For Gael!" in memory of a departed shipmate, prior to strikes on Japanese targets, circa May 1945. |

|

| One of VMF-112's Chance Vought F4U Corsairs after hitting the USS Bennington's island and burning. |

|

| Another crash on the flight deck of the USS Bennington as seen from an aircraft. |

|

| Some of the Bennington's 62 20mm guns during gunnery practice. |

|

| New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, New York. Aerial photograph, taken 9 March 1944. USS Missouri (BB-63) is fitting out in the center. Carrier at the bottom is probably USS Bennington (CV-20). |

|

| Curtiss SB2C Helldiver approach, USS Bennington, 1945. |

|

| Curtiss SB2C Helldiver just landed, USS Bennington, 1945. |

|

| Curtiss SB2C Helldiver landing, USS Bennington, 1945. |

|

| Curtiss SB2C just landed, USS Bennington, 1945. |

|

| General Motors TBM Avenger readying for deck launch, USS Bennington. |

|

| USS Bennington, CV-20 score board: Japanese Planes (left), 177; Ships (right), 35. Grumman F6F Hellcat parked alongside ship's island. |

|

| Grumman F6F Hellcat on USS Bennington flight deck. |

|

| Aft 5-inch guns firing, USS Bennington. |

|

| View of U.S. cruiser as seen from USS Bennington. |

|

| Planes spotted aft on the flight deck, USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| Air operations on the USS Bennington. |

|

| The USS Bennington going under the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco Bay. |

|

| USS Bennington, 1945. |

|

| Grumman F6F-5 Hellcats of Fighting Squadron 81 (VF-81) are parked on the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-18). Note that the individual aircraft numbers have been incorporated into the geometric air group identification symbol (a horizontal white stripe). In the background to the left is USS Bennington (CV-20) and to the right is USS Hornet (CV-12). |

|

| Town Offices in Bennington, Vermont, showing the USS Bennington ship's bell. |

|

| Another view of the ship's bell in Bennington, Vermont. |

|

| Close-up of the ship's bell in Bennington, Vermont. |

|

| Plaque on the reverse of the marble display in Bennington, Vermont. |