Interrogation NAV No. 4/USSBS No. 40

Tokyo, 18 October 1945

Interrogation of

Captain Fuchida, Mitsuo, IJN, a naval aviator since 1928. As air group commander of the Akagi he led the attacks on Pearl Harbor, Darwin and Ceylon. In April 1944 he became Air Staff Officer to Commander-in-Chief Combined Fleet and held that post for the duration of the war.

Interrogated by

Lieutenant Commander R. P. Aiken, USNR.

Allied Officers Present

Colonel Phillip Cole, U.S. Army; Captain W. Pardae, U.S. Army; Lieutenant Robert Garred, USNR.

Summary

Captain Fuchida discussed the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the organization of the Kamikaze Corps during the Philippine Campaign. He also furnished information relating to suicide attacks during the Okinawa Campaign, and Japanese Naval and Army Air Forces plans to resist an invasion of Japan proper.

Transcript

What was your status during the Pearl Harbor attack?

I was an air observer.

How many and what types of aircraft were used in the attack?

A total of 350. In the first wave:

50 High level bombers: Kates

40 Torpedo bombers: Kates

50 Dive bombers: Vals

50 Fighters: Zekes

In the second wave:

50 High level bombers: Kates

80 Dive bombers: Vals

40 Fighters: Zekes

How many aircraft were lost; failed to return to their carriers?

Twenty-nine in all. Nine fighters in the first wave and fifteen dive bombers and five torpedo bombers in the second wave.

Which units of the fleet participated in the Pearl Harbor attack?

Battleships Hiei, Kirishima.

Carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku, Zuikaku.

Heavy cruisers Tone, Chikuma.

Light cruiser Nagara.

Destroyers—twenty (large type).

How many aircraft were employed as Combat Air Patrol (CAP) over the Pearl Harbor attack force?

Fifty fighters from carriers plus twelve float planes from the battleships, heavy and light cruisers. These were in addition to the 350 planes used in the actual attack at Pearl Harbor.

How many CAP were on station at a time?

About one-third of the fifty aircraft were airborne at a time.

Any losses from CAP, either fighters or float planes?

None.

Any additional planes employed as ASP?

None, fighters served as ASP as well as CAP.

How many pilots were lost in the attack?

A total of twenty-nine—none were recovered from the twenty-nine aircraft that failed to return.

Philippine Kamikaze Operations

Were the carrier air groups, that left the Empire in October 1944 being sent to the Philippines for Kamikaze attacks?

No. Part of the 601 Air Group was embarked in October 1944. From the remainder of the air group pilot personnel, thirty fighter pilots were selected in November 1944 for Kamikaze operations and were sent to Luzon, to join the 201 Air Group.

Were any of the 601 Air Group, embarked on carriers in October 1944, being sent to the Philippines defense as Kamikaze pilots?

No.

How were the thirty fighter pilots selected for Kamikaze operations?

They were all volunteers.

How did they rank in flying experience with the other pilots in the air group?

They were the best.

Regarding Japanese plans for the defense of the homeland against Allied landings, how were Kamikaze aircraft to be employed ?

According to plans, all Kamikaze planes were to be expended when Allied forces attempted landings on Kyushu.

Were any Kamikaze planes to be held back for the defense of the Kanto Plain Area?

On paper, all aircraft (both Army and Navy combat and trainer types) were to be used to resist Allied amphibious operations against Kyushu. Actually, I believe that some Army Air units would have been held back to repel an invasion of the Kanto Plain.

At Okinawa, what was the ratio of ships hit to aircraft expended in Kamikaze attacks?

I think about one-sixth of the total aircraft used hit their target.

How many Kamikaze aircraft were expended during the Okinawa operations?

About nine hundred in all.

500 Navy aircraft from Japan;

300 Army aircraft from Japan;

50 Navy aircraft from Formosa;

50 Army aircraft from Formosa.

These figures are approximations.

Of the nine hundred that were expended in the Okinawa Area, how many hit their target?

Although it was widely publicized that four hundred had been successful, I think that two hundred would be a more accurate figure.

What percentage of hits did the Japanese Naval Air Force expect in the Ketsu Operations?

We expected about the same percentage as during the Okinawa operations.

How many Kamikaze aircraft were to be used during Ketsu Operations by the Japanese Naval Air Force?

Twenty-five hundred, of which five hundred were combat aircraft and two thousand were trainers. We had about twenty-five hundred remaining combat aircraft which would be used during Ketsu Operations for search, night torpedo, and air cover.

What were the plans for the use of the Kamikaze aircraft during Ketsu Operations?

Five hundred suicide planes were to be expended during the initial Allied landing attempt. This force would be supplemented by other Kamikaze units brought in from Shikoku, southwest Honshu, central Honshu, the Tokyo area, and Hokkaido.

How were the Japanese Naval Air Force Kamikaze aircraft deployed throughout the Empire?

500 in Kyushu.

500 in southwest Honshu.

500 in central Honshu.

500 in Tokyo area.

300 in Hokkaido.

200 in Shikoku.

What was the size and deployment of the Japanese Army Air Force Kamikaze Force?

Approximately the same as the Japanese Naval Air Force. Twenty-five hundred aircraft deployed similarly.

|

| Mitsuo Fuchida, wearing the white cap, who led the attack on Pearl Harbor, stands with his men the day before the attack. |

|

| Captain Mitsuo Fuchida. |

|

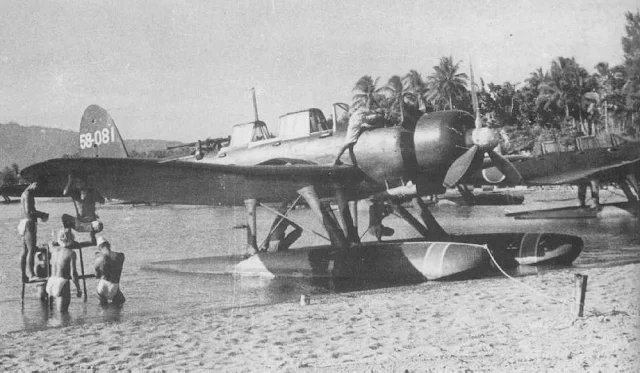

| Lt. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida training for the Pearl Harbor attack, October 1941. |