The Waco CG-4 was the most widely used American troop/cargo

military glider of World War II. It was designated the CG-4A by the United

States Army Air Forces, and given the service name Hadrian (after the Roman

emperor) by the British.

The glider was designed by the Waco Aircraft Company. Flight

testing began in May 1942. More than 13,900 CG-4As were eventually delivered.

Design and Development

The CG-4A was constructed of fabric-covered wood and metal

and was crewed by a pilot and copilot. It had two fixed mainwheels and a

tailwheel.

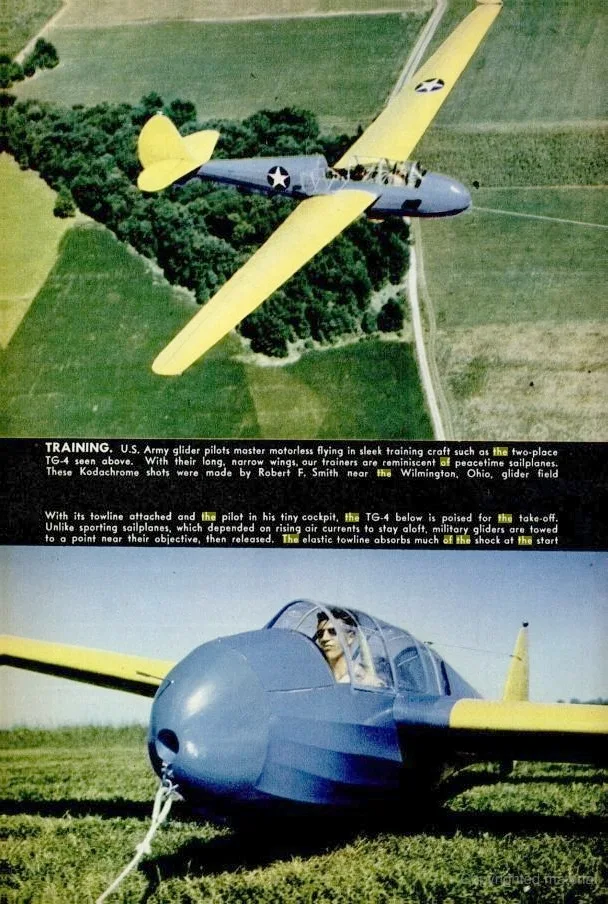

The CG-4A could carry 13 troops and their equipment. Cargo

loads could be a 1⁄4-ton truck (i.e. a Jeep), a 75 mm howitzer, or a 1⁄4-ton

trailer, loaded through the upward-hinged nose section. Douglas C-47 Skytrains

were usually used as tow aircraft. A few Curtiss C-46 Commando tugs were used

during and after the Operation Plunder crossing of the Rhine in March 1945.

The USAAF CG-4A tow line was 11⁄16 inch (17 mm) nylon, 350

feet (110 m) long. The CG-4A pickup line was 15⁄16 inch (24 mm) diameter nylon,

but only 225 ft (69 m) long including the doubled loop.

In an effort to identify areas where strategic materials

could be reduced, a single XCG-4B was built at the Timm Aircraft Corporation

using wood for the main structure.

Production

From 1942 to 1945, the Ford Motor Company's "Iron

Mountain" plant in Kingsford, Michigan, built 4,190 CG-4A gliders (more

than any other company in the nation) at a lower per-unit cost than any other

manufacturer.

The 16 companies that were prime contractors for

manufacturing the CG-4A were:

Babcock Aircraft

Company of DeLand, Florida (60 units at $51,000 each)

Cessna Aircraft

Company of Wichita, Kansas (750 units); the entire order was actually

subcontracted to Boeing Aircraft Company's new Wichita plant.

Commonwealth

Aircraft of Kansas City, Kansas (1,470 units)

Ford Motor

Company of Kingsford, Michigan (4,190 units at $14,891 each)

G&A Aircraft

of Willow Grove, Pennsylvania (627 units)

General Aircraft

Corporation of Astoria, Queens, New York) (1,112 units)

Gibson

Refrigerator of Greenville, Michigan (1,078 units)

Laister-Kauffman

Corporation of St. Louis, Missouri (310 units)

National

Aircraft Corporation of Elwood, Indiana (one unit, at an astronomical

$1,741,809)

Northwestern

Aeronautical Corporation of Minneapolis, Minnesota (1,510 units)

Pratt-Read of

Deep River, Connecticut (956 units)

Ridgefield

Manufacturing Company of Ridgefield, New Jersey (156 units)

Robertson

Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis, Missouri (170 units)

Timm Aircraft

Company of Van Nuys, California (434 units)

Waco Aircraft

Company of Troy, Ohio (1,074 [999] units at $19,367 each)

Ward Furniture

Company of Fort Smith, Arkansas (7 units)

The factories ran 24-hour shifts to build the gliders. One

night-shift worker in the Wicks Aircraft Company factory in Kansas City wrote,

On one side of the huge bricked-in room is a fan running, on

the other a cascade of water to keep the air from becoming too saturated with

paint. The men man the paint sprayers covering the huge wings of the glider

with the Khaki or Blue and finishing it off with that thrilling white star

enclosed in a blue circle that is winging its way around the world for victory

... The wings are first covered with a canvas fabric stretched on like

wallpaper over plywood then every seam, hold, open place, closed place, and

edge is taped down with the all adhesive dope that not only makes the wings

airtight, but covers my hands, my slacks, my eyebrows, my hair, and my tools

with a fast-drying coat that peels off like nail polish or rubs off with a thinner

that burns like Hell.

Type: Military glider

Manufacturer: Waco Aircraft Company

Built by:

Cessna

Ford

Gibson Appliance

Primary users:

United States Army Air Forces

Royal Air Force

Royal Canadian Air Force

United States Navy

Number built: 13,909

First flight: 1942

Variants: Waco CG-15

Operational History

Sedalia Glider Base was originally activated on 6 August 1942.

In November 1942 the installation became Sedalia Army Air Field, (after the war

would be renamed Whiteman Air Force Base) and was assigned to the 12th Troop

Carrier Command of the United States Army Air Forces. The field served as a

training site for glider pilots and paratroopers. Assigned aircraft included

the CG-4A glider, Curtiss C-46 Commando, and Douglas C-47 Skytrain. The C-46

was not used as a glider tug in combat, however, until Operation Plunder (the

crossing of the Rhine) in March 1945.

CG-4As went into operation in July 1943 during the Allied

invasion of Sicily. They were flown 450 miles across the Mediterranean from

North Africa for the night-time assaults such as Operation Ladbroke.

Inexperience and poor conditions contributed to the heavy losses. They

participated in the American airborne landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944, and

in other important airborne operations in Europe and in the China Burma India

Theater. Although not the intention of the Army Air Forces, gliders were

generally considered expendable by high-ranking European theater officers and

combat personnel and were abandoned or destroyed after landing. While equipment

and methods for extracting flyable gliders were developed and delivered to

Europe, half of that equipment was rendered unavailable by certain

higher-ranked officers. Despite this lack of support for the recovery system,

several gliders were recovered from Normandy and even more from Operation

Market Garden in the Netherlands and Wesel, Germany.

The CG-4A found favor where its small size was a benefit.

The larger British Airspeed Horsa could carry more troopers (seating for 28 or

a jeep or an anti-tank gun), and the British General Aircraft Hamilcar could

carry 7 tons (enough for a light tank), but the CG-4A could land in smaller

spaces. In addition, by using a fairly simple grapple system, an in-flight C-47

equipped with a tail hook and rope braking drum could "pick up" a

CG-4A waiting on the ground. The system was used in the 1945 high-elevation

rescue of the survivors of the Gremlin Special 1945 crash, in a mountain valley

of New Guinea.

The CG-4A was also used to send supplies to partisans in

Yugoslavia.

After World War II ended, most of the remaining CG-4As were

declared surplus and almost all were sold. Many were bought for the wood in the

large shipping boxes. Others were bought for conversion to towed camping homes

with the wing and tail end cut off and being towed by the rear section and

others sold for hunting cabins and lake side vacation cabins.

The last known use of the CG-4A was in the early 1950s by

the USAF with an Arctic detachment aiding scientific research. The CG-4As were

used for getting personnel down to, and up from, floating ice floes, with the

glider being towed out, released for landing, and then picked up later by the

same type of aircraft, using the hook and line method developed during World

War II. The only modification to the CG-4A was the fitting of wide skis in

place of the landing gear for landing on the Arctic ice floes.

Variants

XCG-4: Prototypes, two built, plus one stress test article

CG-4A: Main production variant, survivors became G-4A in

1948, 13,903 built by 16 contractors

XCG-4B: One Timm-built CG-4A with a plywood structure

XPG-1: One CG-4A converted with two Franklin 6AC-298-N3

engines by Northwestern

XPG-2: One CG-4A converted with two 175 hp (130 kW) Ranger

L-440-1 engines by Ridgefield

XPG-2A: Two articles: XPG-2 engines changed to 200 hp (150

kW) plus one CG-4A converted also with 200 hp (150 kW) engines

PG-2A: Production PG-2A with two 200 hp (150 kW) L-440-7s,

redesignated G-2A in 1948, 10 built by Northwestern

XPG-2B: Cancelled variant with two R-775-9 engines

LRW-1: CG-4A transferred to the United States Navy (13

units)

G-2A: PG-2A re-designated in 1948

G-4A: CG-4A re-designated in 1948

G-4C: G-4A with different tow-bar, 35 conversions

Hadrian Mk.I: Royal Air Force designation for the CG-4A, 25

delivered

Hadrian Mk.II: Royal Air Force designation for the CG-4A

with equipment changes

Operators

Canada: Royal Canadian Air Force

Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovak Air Force operated 2 Wacos,

designated NK-4

United Kingdom:

Army Air Corps

Glider Pilot Regiment

Royal Air Force

No. 668 Squadron RAF

No. 669 Squadron RAF

No. 670 Squadron RAF

No. 671 Squadron RAF

No. 672 Squadron RAF

No. 673 Squadron RAF

United States:

United States Army Air Forces

United States Navy

Accidents and Incidents

1 August 1943: CG-4A-RO 42-78839, built by contractor

Robertson Aircraft Corporation, lost its right wing and plummeted to earth

immediately after release by a tow airplane over Lambert Field, St. Louis,

Missouri, USA. Several thousand spectators had gathered for the first public

demonstration of the St. Louis-built glider, which was flown by 2 USAAF crewmen

and carried St. Louis mayor William D. Becker, Robertson Aircraft co-founder

Maj. William B. Robertson, and 6 other VIP passengers; all 10 occupants

perished in the crash. The accident was attributed to the failure of a

defective wing strut fitting that had been provided by a subcontractor; the

post-crash investigation indicted Robertson Aircraft for lax quality control;

several inspectors were relieved of duty.

Surviving Aircraft

42-43809 – On

display at the Museum of Army Flying in Middle Wallop, Hampshire.

45-13696 – CG-4A

under restoration at the Yanks Air Museum in Chino, California.

45-14647 –

Cockpit section on static display at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson,

Arizona.

45-15009 – CG-4A

on static display at the Air Mobility Command Museum at Dover Air Force Base

near Dover, Delaware.

45-15574 – On

static display at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, New York.

45-15691 – On

display at the Silent Wings Museum in Lubbock, Texas.

45-15965 – On

display at the Kalamazoo Air Zoo in Portage, Michigan. It is painted as

42–46574.

45-17241 – On

static display at the Airborne Museum in Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy.

45-27948 – CG-4A

on static display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in

Dayton, Ohio.

Replica – On

display at the Fagen Fighters WWII Museum in Granite Falls, Minnesota.

Replica – On

display at The Fighting Falcon Museum in Greenville, Michigan.

Unknown – On

display at the Menominee Range Historical Foundation in Iron Mountain,

Michigan.

Unknown – CG-4A

on display at the National Soaring Museum in Elmira, New York.

Unknown – Cockpit

section on display at the Travis Air Force Base Heritage Center in Fairfield,

California.

CG-4A on display

at the Silent Wings Museum in Lubbock, Texas.

Unknown – CG-4A

on display at the Don F. Pratt Memorial Museum at Fort Campbell near

Clarksville, Tennessee.

Unknown – CG-4A

on static display at the Yorkshire Air Museum in Elvington, Yorkshire.

Unknown – On

display at the Assault Glider Trust in Shawbury, Shropshire.

Unknown – On

static display at the Airborne & Special Operations Museum in Fayetteville,

North Carolina.

Unknown – On

static display during restoration at the U.S. Veterans Memorial Museum in

Huntsville, Alabama.

Replica - A CG-4

'Hadrian' nose section is on display at the South Yorkshire Aircraft Museum,

Doncaster, United Kingdom. The replica was produced for the film Saving Private

Ryan.

Specifications (CG-4A)

Crew: two pilots

Capacity: 13 troops, or quarter-ton truck (Jeep) and 4

troopers, or 6 litters and 4,197 pounds (1,904 kg) useful load

Length: 48 ft 8 in (14.8 m)

Wingspan: 83 ft 8 in (25.5 m)

Height: 15 ft 4 in (4.7 m)

Wing area: 900 sq ft (83.6 m2)

Empty weight: 3,900 lb (1,769 kg)

Gross weight: 7,500 lb (3,402 kg)

Maximum takeoff weight: 7,500 lb (3,402 kg)

Maximum take off (Emergency Load): 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg)

Maximum speed:

150 mph (240 km/h, 130 kn) CAS] at

7,500 pounds (3,400 kg)

128 mph (206 km/h) CAS/135 mph (217

km/h) IAS at 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg)

Cruise speed: 73 mph (117 km/h, 63 kn) IAS

Stall speed: 49 mph (79 km/h, 43 kn) with design load 7,500

pounds (3,400 kg)

Never exceed speed: 150 mph (241 km/h, 130 kn) IAS

Maximum glide ratio: 12:1

Wing loading: 8.33 lb/sq ft (40.7 kg/m2)

Rate of sink: About 400 ft/min (2 m/s) at tactical glide

speed (IAS 60 mph; 97 km/h)

Landing run: 600–800 feet (180–240 m) for normal three-point

landing; "Landing rolls of approximately 2,000 to 3,000 feet (610 to 910

m) are to be expected at the higher emergency gross weights..."

Bibliography

AAF Manual No.

50-17, Pilot Training Manual for the CG-4A Glider. US Government, 1945.

AAF TO NO.

09-40CA-1, Pilot's Flight Operating Instructions for Army Model CG-4A Glider,

British Model Hadrian. US Government, 1944.

Andrade, John M.

U.S. Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909. Earl Shilton,

Leister, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 1979.

Diehl, Alan E.,

PhD. Silent Knights: Blowing the Whistle on Military Accidents and Their

Cover-ups. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's, Inc., 2002.

Fitzsimons,

Bernard, ed. "Waco CG-4A." Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century

Weapons and Warfare, Volume 11. London: Phoebus, 1978.

Gero, David B.

Military Aviation Disasters: Significant Losses Since 1908. Sparkford, Yoevil,

Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing, 2010.

Masters, Charles

J., Glidermen of Neptune: The American D-Day Glider Attack Carbondale,

Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995.

Soukup, Oldřich

(1979). "Kluzáky Československého Vojenského Letectva (I.)"

[Czechoslavak Military Gliders (I.)]. Letectví a Kosmonautika (in Czech). Vol.

55, no. 18. pp. 693–695.

|

The 101st Airborne Division was reinforced with twelve glider serials on September 18. Here, Waco gliders are lined up on an English airfield in preparation for the next lift to Holland. 1944.

(U.S. Army Signal Corps) |

|

German troops examine an abandoned Waco, Normandy, June 1944.

(Bundesarchiv Bild 146-2004-0176) |

|

Waco XPG-1 powered glider prototype.

(U.S. Army Air Forces) |

|

Waco XPG-2 powered glider.

(U.S. Army Air Forces) |

|

Waco PG-2A.

(Erection and Maintenance Instructions for Model PG-2A Glider, AN 09-75DA-2, 1946, 2. Provided by the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Dayton, Ohio.) |

|

| A British Hadrian. |

|

A U.S. Army Air Force Waco CG-4A-GN glider (s/n 45-27948) at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, at Dayton, Ohio, 5 May 2006.

(National Museum of the U.S. Air Force photo 060505-F-1234P-005) |

|

Cockpit of a CG-4A at the Silent Wings Museum, 2008.

|

|

| Waco CG-4A. |

|

Page from manual specifying loads: as well as being able to carry up to 13 airborne troops or 6 litters of wounded men, the CG-4 could also carry such loads as a field kitchen, an anti-tank gun, a weather station, radar or radio equipment, a repair shop, a howitzer, a photographic laboratory, or a quarter-ton truck.

(Pilot Training Manual for the CG-4A Glider) |

|

A U.S. Army Air Force Waco CG-4A glider.

(USAAF) |

|

A U.S. Army Air Force Waco CG-4A glider on display in October 1944.

Original description: "CG-4A glider used to carry utility and service units. It is also a standard troop carrier glider which has been used in every invasion from Sicily through Holland. It carries about 3,700 pounds or 15 fully equipped men. Note efficient assembly of service units in this picture."

(United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

under the digital ID fsa.8d36830)

| |

|

The HQ Divisional Artillery of the 101st Airborne Division troops that landed behind German lines in Holland examine what is left of one of the gliders that "cracked up." September 1944.

(US Army Signal Corps / US Army Military History Institute / Photo Courtesy of U.S. Army) |

|

C-47 of 62d Troop Carrier Squadron, the 314th Troop Carrier Group, and Waco gliders, at RAF Saltby, England. 1944.

(USAAF) |

|

CG-4a Waco Glider of the 315th Troop Carrier Group - RAF Aldermaston, 1943.

(USAAF) |

|

Members of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment prepare a weapon for stowage aboard a glider. April 1943.

(US Army) |

|

CG4A Glider, 61st Troop Carrier Group.

(USAAF) |

|

OPERATION 'MARKET GARDEN' (THE BATTLE FOR ARNHEM): 17 - 25 SEPTEMBER 1944. An aerial view of a C-47 Dakota as it tows off a CG-4A Waco glider from a British airfield en route for Holland. 17 Sep 1944.

(Imperial War Museum EA37974) |

.jpg) |

U.S. Army Air Forces Douglas C-47'S tow planes and Waco CG-4 gliders of the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing at Ponte Olivo Airfield, Sicily (Italy), 25 October 1943.

(National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 204919613) |

.jpg) |

Aerial view of some of the 50 Waco GC-4A gliders after their landing near Bastogne, Belgium, 27 December 1944. The gliders were towed by 37 Douglas C-47 Skytrains from the 439th Troop Carrier Group and 13 from the 440th TCG from Châteaudun airfield (A-39), France.

(National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 148728180) |

.jpg) |

British Airspeed Horsa and U.S. Waco CG-4 gliders on a field in Germany during "Operation Varsity", 24 March 1945.

(National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 204899674) |

|

Hadrian Mark I, FR579 “Voo Doo”, arriving at Prestwick after being towed, in a series of stages, across the Atlantic from Canada. FR579 served with No. 21 Heavy Glider Conversion Unit and the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment.

(Imperial War Museum CH10470) |

1235.jpg) |

Hadrian Mark I, probably FR557, under tow at the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment, Sherburn-in-Elmet, Yorkshire.

(Imperial War Museum E(MOS)1235) |

|

CG-4A Waco Gliders landing at the unfinished Beuzeville Airfield (A-6), France, 1944.

(USAAF) |

|

Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe, artillery commander of the 101st Airborne Division, gives his various glider pilots last-minute instructions in England on Sept. 18, 1944, before the take-off on D-Day plus 1.

(USAF) |

|

Translation of original German caption: "Shot-down gliders in the Dutch combat zone. The airborne troops dropped by the enemy in the Dutch combat zone often suffered heavy losses from German ground defenses even before they landed. Countless gliders were destroyed by German fighters and anti-aircraft artillery, some before reaching the ground, some immediately after landing. The crews either died in combat or were captured." Press photo, war correspondent Linden (Scherl Picture Service), September 27, 1944 [date of issue]"

Arnhem, Sep 1944.

(Bundesarchiv Bild 183-J27727) |

|

U.S. Army Air Forces Douglas C-47A Skytrain (43-15174 in front) from the 88th Troop Carrier Squadron, 438th Troop Carrier Group, 53rd Troop Carrier Wing, 9th Troop Carrier Command, tow Waco CG-4A gliders during the invasion of France in June 1944.

On 6 June 1944, the squadron dropped the 101st Airborne Division's 502d Parachute Infantry Regiment soon after midnight in the area northwest of Carentan, France. Glider-borne reinforcement missions followed, carrying weapons, ammunition, rations, and other supplies.

The Douglas C-47B-15-DK, s/n 43-49507 (c/n 26768), is today on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, painted as 43-15174 of the 88th TCS. 43-49507 was the last C-47 in USAF service and was retired at the museum on 30 June 1975 with a total of 20,821 hours flying time.

(National Museum of the U.S. Air Force photo 050606-F-1234P-039) |

|

U.S. Army Air Force Douglas C-47 Skytrain transports and Waco CG-4A gliders lined up for "Operation Varsity" on 24 March 1945.

(U.S. Air Force photo in the official USAF publication The Army Air Forces in World War II Volume 3 - Europe: Argument to V-E Day, p. 745) |

|

C-47s with CG-4 Waco Gliders just before D-Day, 1944, 316th Troop Carrier Group, 37th TCS.

(United States Army Air Force from National Archives) |

|

CG-4A on display at the Silent Wings Museum. 22 Nov 2022.

(Sclemmons) |

|

A wrecked U.S. Army Air Force Waco CG-4A glider (s/n 42-73623) in Sicily in July 1943.

(U.S. Air Force photo in the official USAF publication The Army Air Forces in World War II Volume 2 - Europe: Torch to Pointblank, p. 424) |

|

CG-4a Gliders of the 442d Troop Carrier Group at Chilbolton airfield just before Operation Market Garden. Sep 1944.

(USAAF) |

|

Cockpit of a WWII Waco CG-4 attack glider from the collection of the Fagen Fighters WWII Museum in Granite Falls, Minnesota. 10 Nov 2018.

(Aaron Headly) |

|

Invasion drawing by Captain Creekmore from D-day invasion of France.

(Raymond Creekmore)

|

|

C-47 and CG-4 Glider, Dalhart Army Airfield. 1943.

(USAAF) |

.jpg) |

A U.S. Army Air Forces Douglas C-47 of the 437th Troop Carrier Group tows two Waco CG-4A gliders at advanced landing ground A-58 Coulommiers, 24 March 1945.

(National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 17471) |

.jpg) |

Glider troops after landing near Wesel, Germany, 24 March 1945.

(US Army) |

|

THE CAMPAIGN IN SICILY 1943. Planning and Preparations January - July 1943: A jeep is loaded onto an American Waco CG-4A glider. July 1943.

Imperial War Museum CNA1662) |

|

Airborne troops exiting CG-4 glider, Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

C-47s towing CG-4A gliders, Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, CG-4A glider landing, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, CG-4A glider ready for snatch pickup by a C-47, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base CG-4A glider taking off after snatch pickup, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, Jeep coming out of front cargo door, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, Jeep coming out of front cargo door, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, unloading artillery from CG-4A glider, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, unloading tractor from CG-4A glider, 1942.

(USAAF) |

|

Douglas C-47s and CG-4A Waco Gliders, of the 436th Troop Carrier Group, lined up on the runway at Membury Airfield, England.

(USAAF) |

.jpg) |

Army engineers prepare to haul a glider off the Myitkyina airfield. 17 May 1944.

(Signal Corps SC 190519) |

.jpg) |

Just before the take-off for Holland, where they landed Sunday afternoon, 17 September, 1944, these gliders are lined up at an airport somewhere in England.

(Signal Corps SC 195697) |

|

Members of an Airborne unit load a jeep into the "mouth" of a glider in preparation for the airborne invasion of Holland which was successfully launched from airports "somewhere" in England. 17 September 1944.

(Signal Corps SC 195698) |

.jpg) |

Lined up with hatches open to receive their cargo, these gliders are part of the 82nd Airborne Div, which invaded Holland from Cottesmore Airdrome, England. 17 September 1944.

(Signal Corps SC 195699) |

.jpg) |

Yanks of an airborne unit close the cargo loading hatch of a glider preparatory to the takeoff from England for the invasion of Holland. 17 September 1944.

(Signal Corps SC 195700) |

.jpg) |

Seated in the shade cast by the tail of a glider, two French women chat with U. S. Army MPs as they await questioning by an Army officer. June 19, 1944..

(Signal Corps) |

|

A Sherman flail tank supports infantry of the 2nd Glasgow Highlanders at the start of Operation 'Veritable', 8 February 1945. In the background are American gliders which landed during Operation 'Market Garden' in September 1944.

(Imperial War Museum BU1693) |

|

The Waco Hadrian glider 'Voo-Doo' the first Hadrian glider to be towed across the Atlantic being unloaded at Prestwick, 28 June 1943.

(Imperial War Museum TR1159) |

|

Waco CG-4A glider at Twenty-nine Palms Air Academy, 1942.

(US Army) |

,_in_1943_(342-FH-3A27180-A67255AC).jpg) |

The U.S. Army Air Forces 52nd Troop Carrier Wing drops paratroopers and releases Waco GC-4 gliders during maneuvers at Ponte Olivo airfield, Sicily (Italy), in 1943.

(National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 204919381) |

|

The U.S. Army Air Forces Waco CG-4A glider with Lt. Suella Bernard in the right-hand seat of the cockpit just as the glider is being snatched by a C-47, circa 1944-45.

(National Museum of the U.S. Air Force photo 090903-F-1234S-017) |

|

Glider used to carry utility and service units. Shown at demonstration of equipment held by United States Army Air Forces. Cargo space is large enough to hold a jeep and six men or a 75mm pack Howitzer, with crew. Oct 1944

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection, reproduction number LC-USW3-055713-E) |

.jpeg) |

Original caption: "Troops of a glider field artillery battalion enter their glider in smart, snappy style, ready to take off for invasion maneuvers."

(U.S. Army Signal Corps) |

|

Original caption: "U.S. Airborne Infantry troops loading a transport glider (Waco CG-4) which will be used in maneuvers in the southwestern United States." 1942.

(United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID fsa.8e00221) |

.jpg) |

U.S. Army Air Forces Waco CG-4A gliders at advanced landing ground A-58 Coulommiers, 21 March 1945. The 437th Troop Carrier Group was based at the airfield at that time.

(National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 17471) |

_-_50546988838.jpg) |

Waco CG-4A ’42-43809’ was built by Gliders & Airplanes of Willow Grove, Pennsylvania in early 1943. On 9th July 1943 it was one of 136 CG-4s used during Operation ‘Ladbroke’, a glider landing of the British 1st Airlanding Brigade at Syracuse, Sicily. ‘Ladbroke’ was the first Allied use of significant number of gliders and was in support of the overall Allied invasion of the island, Operation ‘Husky’. Tragically, 65 gliders were released early by their towing aircraft and some 252 soldiers drowned when the gliders had to ditch in the sea. The forces that did successfully make landfall held the Ponte Grand Bridge, the main objective, until after the time that they should have been relieved, but eventually had to surrender to Italian forces.

This exhibit is based around an original CG-4 frame which joined the collection, from France, in 1985. It seems unlikely that the identity is genuine for this airframe, but she is an impressive exhibit representing a significant operation. She has been allocated the British Aircraft Preservation Council identity BAPC185. Army Flying Museum Middle Wallop, Hampshire, UK. 21 Aug 2020.

(Alan Wilson) |

.jpg) |

View of the front of the same CG-4A glider as in the above photo.

(Alan Wilson) |

|

| Waco CG-4A. |

|

| C-47 takes off towing a Waco CG-4A glider. |

|

| Pilot and co-pilot in the cockpit of a Waco C G-4A glider. |

|

A Waco CG-4A glider flips on its nose while landing during Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France.

|

|

| A Waco CG-4A glider flown by the 1st Air Commando, is being used by OSS Detachment 101 in Burma in 1944. |

|

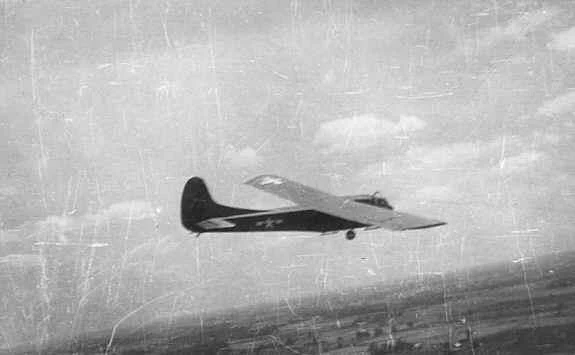

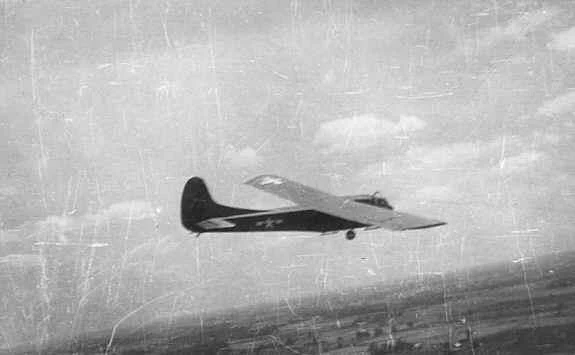

| Waco CG-4A in flight. |

|

| Waco CG-4A gliders lining up on an airstrip in Sicily, Italy, August 1943. |

|

| C-47 Skytrain aircraft towing two CG-4A gliders during a training exercise. |

|

| View from cockpit of a CG-4A glider as it was towed by a C-47 Skytrain aircraft, 1944 |

|

| A CG-4A cargo glider of the 439th Troop Carrier Group takes off from air base A-39 Châteaudun, France. 27 December 1944. |

|

| Service Command mechanics attach a wing to one of the gliders at Crookham Common, England. |

|

| CG-4A glider assembly yard. |

|

| CG-4A gliders in a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Preparing CG-4A wings for attachment to the fuselage. |

|

| Glider mechanic working on a CG-4A glider interior at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Assembling the tail of a CG-4A glider at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Attaching the tail units to a CG-4A glider at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| The cockpit of a CG-4A glider. |

|

| CG-4A fuselages ready for wings and tail units at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| CG-4A gliders assembled at a glider assembly yard and ready for service. |

|

| CG-4A glider fuselage being readied at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Attaching the main wheels to the fuselage of a CG-4A glider at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| A C-47 tows two CG-4A gliders to their new home after being assembled at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Dozens of CG-4A gliders, ready for service, awaiting tows to their new home with a glider unit. |

|

| Two CG-4A gliders ready to be towed by a C-47 to their new home with a glider unit after being assembled at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| CG-4A Glider above Columbus, Indiana, 1945. |

|

| Pilot at the controls of a CG-4A glider. |

|

| Co-pilot of the same CG-4A glider as in the previous photo. |

|

| View from the cockpit of a CG-4A glider under tow by a C-47. 1943. |

|

| Used effectively in Burma. After unloading equipment loaded up with stretcher and walking wounded and then snatched out. Returned to Hospital in about two hours as opposed to two months by ambulance. |

|

| Glider at rest is being snatched airborne by C-47, a picture of the pick-up of the first glider to be recovered from the Normandy landings. It was taken on 23 June 1944 as the glider was being snatched from a field just southeast of St. Mere Eglise, by 1st Lt. Gerald "Bud" Berry, 91st Troop Carrier Squadron, 439th Troop Carrier Group. |

|

| C-47 about to “snatch” a fully-loaded CG-4A glider. |

|

| This is a close up of the hook mechanism of the CG-4A glider from the backside. The back of the instrument panel is also visible. Some installations had the hook mechanism mounted at the top of the windshield. |

|

| Glider tow release mechanism. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider in flight. |

|

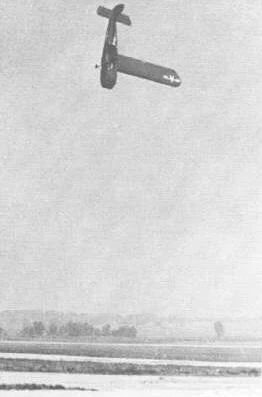

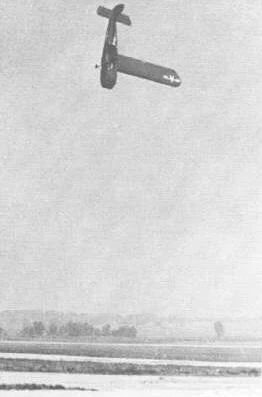

| Robertson Aircraft Company in St. Louis was contracting to build Waco CG-4A-RO gliders under license. Several VIPs were getting a demonstration ride on 1 August 1943. Among the passengers was the Mayor of St. Louis, William D. Becker. Mayor Becker was an experienced pilot himself. All ten souls aboard were killed when a wing separated from their glider shortly after it dropped off tow from a C-47 at 2,000 feet over Lambert Field. The photo shows the glider with left wing missing, pointed almost straight down. Robertson had subcontracted with a local casket maker for some of the parts, and the investigation showed they had used substandard materials for the critical wing attachment. |

|

| C-47 tow planes and Waco CG-4A gliders over the mountains of Burma. |

|

| Looking towards the cockpit inside a CG-4A glider. |

|

| “General George,” CG-4A being unloaded, 1st Air Commando Group. |

|

| A jeep exits a CG-4A glider. |

|

| Loading a jeep into a CG-4A glider by lifting the hinged pilot’s compartment. |

|

| Landing at night in the pitch-black Burmese jungle caused these two CG-4A gliders to crash into each other. Many were killed in the landings on the first night. |

|

| CG-4A and Horsa gliders littering Normandy fields amongst the hedgerows, France. June 1944. |

|

| Waco CG-4 with 101st Airborne glidermen. Readying themselves for the always nerve-wracking flight in a CG-4A glider, men of the 101st Airborne Division join in a domestic training operation. This illustration gives an idea of the Waco’s tubular steel and canvas construction (including the hinged nose section, forward), and furnishes a fine glimpse of standard American infantry small arms in the hands of the glidermen. Note BAR, M1 Garand, Thompson M1A1, M1A1 Bazooka, Springfield 1903. Circa early 1944. |

|

| Glider pilot Charlie Rex (on right) and the Glider Engineering section of the 315th Troop Carrier Group posing in front of CG-4A glider “Hiya Honey.” 1943. |

|

| CG-4A gliders land after being towed to the coast of southern France by Douglas C-47 transports of the Twelfth Air Force Troop Carrier Air Division, on the invasion's D-Day. Dust can be seen as the gliders land somewhere between Cannes and Toulon. 15 August 1944. |

|

| CG-4A glider packing cases in a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Atterbury Army Air Field. A C-47 is taking off but not yet airborne, while the CG-4A glider it is towing is already in the air, 1945. |

|

| USAAF metal Glider Pilot Wings. |

|

| Glider Infantry Badge. |

|

| USAAF cloth glider pilot wings. |

|

| USAAF Troop Carrier Command demonstrating loading wounded men onto a CG-4A glider, Roosevelt Field, Long Island, New York. 24 Mar 1945. Note Dodge WC54 ambulance. |

|

| CG-4A Waco glider of the 315th Troop Carrier Group, RAF Aldermaston, 1943. |

|

| C-47 of the 62nd Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, and Waco CG-4A gliders, at RAF Saltby, England. |

|

| C-47 Skytrain aircraft towing CG-4A glider off an Algerian airstrip. 1943. |

|

| A line of Waco CG-4A gliders. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider in flight. |

|

| A CG-4A glider coming in for a test landing with a 10-foot nylon drag parachute serving as a giant air brake. Parachutes enabled gliders to land more quickly on small fields. They were used extensively during landings in Europe. This test glider is also equipped with a Griswold Nose. |

|

| CG-4A gliders of the 313th Troop Carrier Group after landing during the Market Garden operation, Holland. 23 September 1944. |

|

| CG-4A gliders and Douglas C-47s of the Ninth Troop Carrier Command lined up along the runway await take off time at Greenham Common air base in England prior to taking part in the invasion of France. 6 June 1944. |

|

| Still from movie footage of a CG-4A glider landing at Son, Holland. Operation Market Garden. September 1944. |

|

| Ford-built CG-4A glider sitting in a pasture, Normandy, France. June 1944. |

|

| C-47 Skytrain aircraft of 315th Troop Carrier Group dropping 41 sticks of 1st Polish Airborne Brigade into Graves, Netherlands. 23 September 1944. Note CG-4A gliders already on the ground. |

|

| Cletrac tractor pulling a CG-4A fuselage out of its packing case at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Working on the fuselage of a CG-4A glider at a glider assembly yard. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider cockpit interior. |

|

| This CG-4A glider of the USAAF Troop Carrier Command from Atterbury Army Air Field didn't quite make it back and landed in Perry Doup's farm field at the corner of the base in 1945. It was "snatched" out of the field by a C-47 tow plane. |

|

| CG-4A glider coming in to land with spoilers on. |

|

| CG-4A glider on long tow as seen from another glider. |

|

| C-47 with a double tow of CG-4A gliders out of Atterbury Army Air Field. |

|

| A double tow line up of CG-4A gliders on the field at Atterbury Army Air Field. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider of the 9th Troop Carrier Command comes in for a landing at Remagen, Germany, to pick up wounded personnel. 21 May 1945. |

|

| U.S. Army Air Forces Waco CG-4A glider with Lt. Suella Bernard in the right-hand seat of the cockpit just as the glider is being snatched by a C-47. |

|

| Glider pick-up ground station unit. |

|

| Glider pick-up unit installed in a Douglas C-47. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider pickup by Douglas C-47. |

|

| A Douglas C-47 of the 9th Troop Carrier Command wings its way at low level toward the upright standards where it will snatch up the nylon tow rope attached to the CG-4A glider, left, during glider snatch pickup after operations in Wesel, Germany. 17 April 1945. |

|

| The snatch is made! |

|

| A CG-4A glider is about to leave the ground in tow of a Douglas C-47 of the Ninth Troop Carrier Command, during a snatch pickup at a glider marshaling area in Wesel, Germany. Note the tractor towing another glider into position for another snatch pickup. 17 April 1945. |

|

| A CG-4A glider of the Ninth Troop Carrier Command loaded with injured soldiers, takes off from a field at Remagen, Germany. 22 March 1945. |

|

| CG-4A taking off after snatch pickup, Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base. 1942. |

|

| A CG-4A glider and C-47 tow plane will deliver its wounded in a matter of minutes rather than the usual days by truck. |

|

| Glider Reclamation: Two weeks' time was all that the engineers of the 82nd Service Group, Ninth Troop Carrier Command, required to place 60 percent of the 300 gliders in flyable condition after the Rees-Wesel airborne invasion. Shown here is a small group that has been reclaimed through snatch pickup methods somewhere in Germany. 1 Spring 1945. |

|

| CG-4A glider production in Kingsford’s Ford Motor Company Plant. |

|

| CG-4A glider on exhibit at the Ford Motor Company Plant in Kingsford for the Army-Navy “E” Award, presented on 24 June 1944. |

|

| Curious Dutch civilians check out a CG-4A glider after landing, Operation Market Garden. September 1944. |

|

| Unloading a 57mm anti-tank gun from a CG-4A glider. |

|

| Loading a trailer into a CG-4A glider. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider in D-Day invasion stripes. Note the unusual placement of the stripes, with the leading white stripe on the fuselage is wrapped around the fuselage insignia, obliterating the white stripe on the right side of the insignia. |

|

| CG-4A glider with Troop Carrier Command insignia on nose. |

|

| CG-4A in aluminum doped finish with Troop Carrier Command insignia on nose. |

|

| Inside view of the front fuselage of a Waco CG-4 glider. |

|

| Inside view of the rear fuselage of a Waco CG-4 glider. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider. |

|

| Waco CG-4A. |

.jpg) |

| Waco CG-4A. |

|

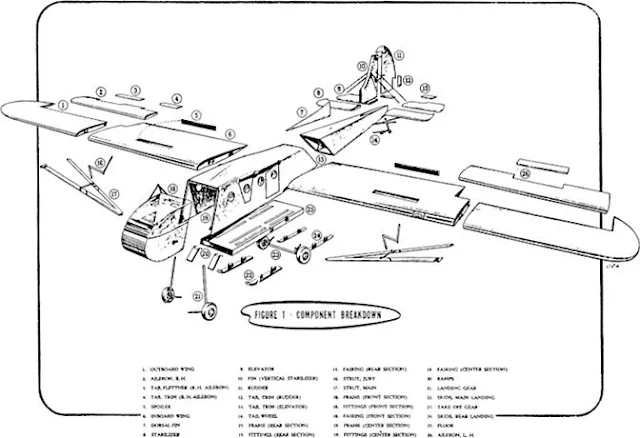

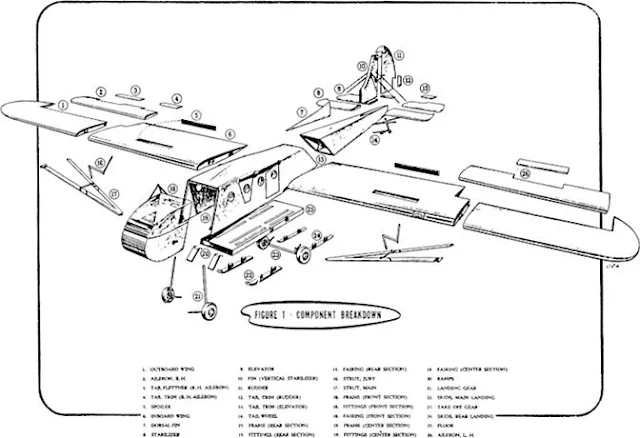

| Waco CG-4A component breakdown. |

|

| Waco CG-4A cockpit and instrument panel. |

|

| Waco CG-4A useful load installation. |

|

| Waco CG-4A modification and reinforcement of windshield. |

|

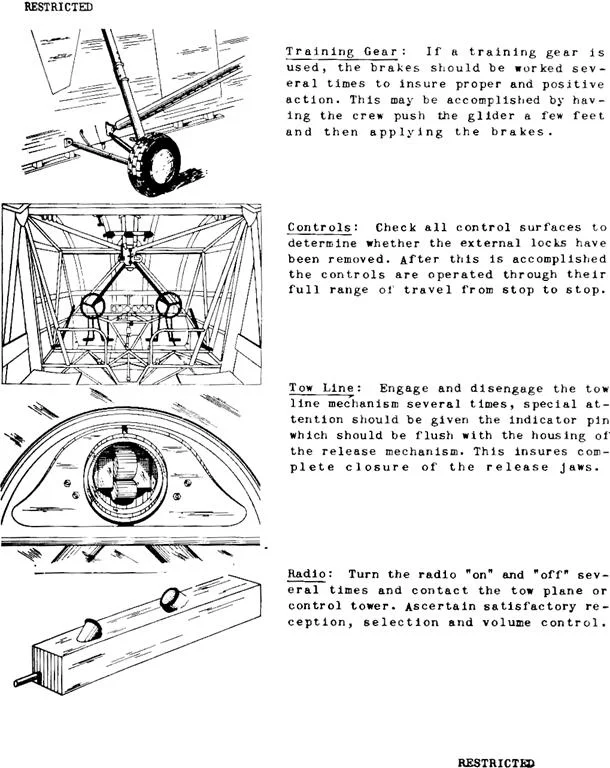

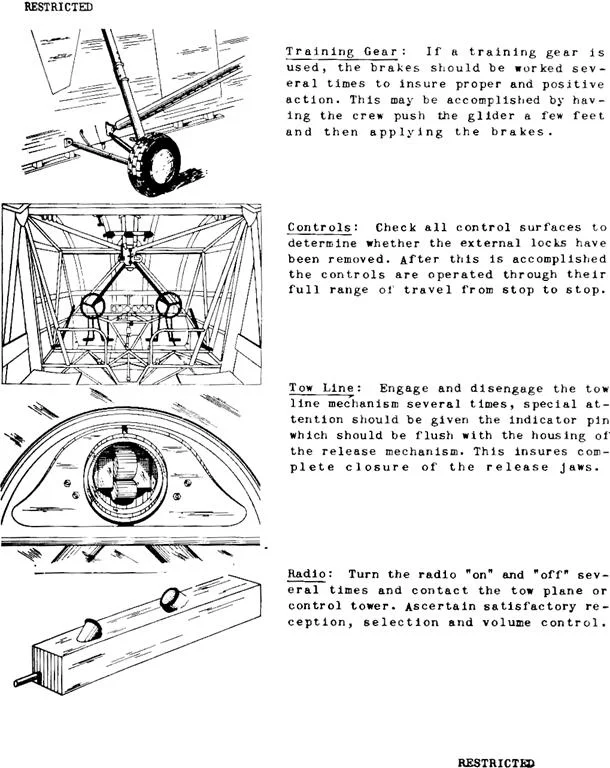

| Waco CG-4A pre-flight inspection manual. |

|

| Waco CG-4A pre-flight inspection manual page. |

|

| Waco CG-4A pre-flight inspection manual page. |

|

| Waco CG-4A pre-flight inspection manual page. |

|

| Waco CG-4A pre-flight inspection manual page. |

|

| Waco CG-4A interphone. |

|

| U.S. glider pilots who ferried assault paratroopers to their D-Day destinations in Normandy are picked up at the beachhead for return to England. |

|

| M1 75mm Pack Howitzer being loaded into a Waco CG-4A glider during training in the U.S. |

|

| Lockheed C-60 Lodestars towing Waco CG-4A gliders over Texas. |

|

| Operation MANNA was one of the Regiment's smaller achievements and was undertaken by members of the Independent Squadron. In brief, its aim was to land troops and equipment at Megara to assist in the liberation and occupation of Athens. On this day, six CG-4As (Hadrians), four of them carrying bulldozers, landed successfully. The following day, a further thirty-four CG-4As did the same with more troops and jeeps. There were no casualties but some interesting experiences. 13/14 October 1944. |

|

| Douglas C-47s and Waco CG-4A gliders of the 8th Troop Carrier Squadron, 62nd Troop Carrier Group, 51st Troop Carrier Wing at Galera Airfield, Italy on 12 August 1944, preparing for Operation Dragoon. This operation consisted of the initial paradrop codenamed Mission Albatross followed by the glider-born landings codenamed Mission Dove and reinforcement drops in Mission Bluebird, and Mission Canary. The 8th TCS insignia on the nearest Skytrain. The 51st TCW based around Rome carried the 2nd Parachute Brigade's first lift except for the 1st Independent Parachute Platoon, who were carried by with the 9th Troop Carrier Command Pathfinder Unit out of Marcigliana Airfield. The 64th TCG at Ciampino Airfield transported the 4th Parachute Battalion and 5th Battalion except for the Support Company Headquarters and "B" Company, who were carried by the 62nd TCG at Galera Airfield along with the 6th Parachute Battalion. Split between these two airfields were Brigade Headquarters, the 2nd Parachute Squadron, and a detachment from the Provost Section. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider in Pittsburgh during World War II. Heinz employees supplied the wings. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. The CG-4A broke down into tail section, main cabin section, cockpit section, inner wing panels, outer wing panels. There were 15,000 board feet of lumber in the five crates a CG-4A came in. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

| Waco CG-4A glider being crated for shipment. |

|

CG-4A Troop Glider being recovered at Wesel, Germany, 1 April 1945.

|

|

| Waco CG-4A taking off. |

|

| Refueling C-47 "Mary Lou". |

|

| Attaching tow rope to C-47. |

|

82nd Airborne Division loading Jeeps into Waco CG-4A gliders. The box in the left Jeep is a SCR-625-C mine detector and a paratrooper bicycle is in the right Jeep, September 1944.

|

|

| Kairouan aerial view. Note tents and glider dispersal, landing field upper left. |

|

| Waco CG-4A setup for transport of wounded on litters. The glider would be loaded and "snatched" by a C-47. |

|

| Note the non-standard national marking on the fuselage. The bars were added when the marking was changed and changes were hastily made and sometimes not to official specifications. |

|

From left to right, they are Mayor of St. Louis, William D. Becker, Thomas Dysart (President, St. Louis Chamber of Commerce), Judge Henry Mueller, Lieut. Colonel Paul Hazelton, and Max Doyne (Director of Public Utilities). These men, and five others - including William B. Robertson, the founder of St. Louis-based Robertson Aircraft Corporation (RAC) (and the builders of the WACO CG-4A troop transport glider pictured), are about to plunge to their deaths during a public demonstration flight. This photo was taken on August 1, 1943, at Lambert Airport (STL / KSTL) in St. Louis.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

1235.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

,_in_1943_(342-FH-3A27180-A67255AC).jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

_-_50546988838.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)