|

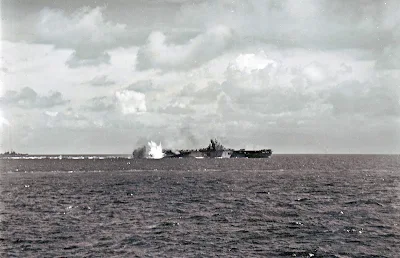

| A near miss off the starboard quarter of USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) on 19 June 1944. The ship and Task Group 58.2 were attacked by Japanese aircraft during operations off the Marianas Islands. |

by Mark L. Evans and Guy J. Nasuti

The first and second U.S. Navy ships named Bunker Hill honored the Revolutionary War battle fought primarily on adjacent Breed’s Hill at Charlestown, Mass., on 17 June 1775. The battle occurred in the midst of the larger siege of the city of Boston, when the Americans learned that the British intended to deploy troops to some of the heights surrounding the city in order to command its vital harbor. Nearly 1,200 patriots marched stealthily onto the peninsula on the night of the 16th and 17th and dug defensive positions. Despite the colonists’ secrecy, the British detected the move and their ships and batteries opened fire on the positions while they landed troops to carry the newly established works. American reinforcements during the battle raised their strength to about 2,400 men, and the British to more than 3,000, though not all the men on either side took a direct part in the fighting. American snipers in Charlestown harassed the British until their ships fired incendiary shot that set much of the town ablaze. In the meanwhile, the British resolutely assaulted the colonist’s positions twice, and both times the patriots, with equal resolution, fired into the regulars and Royal Marines and scythed them down. The British regrouped and attacked a third time as the patriots began to run out of ammunition, and finally drove the Americans back at the point of the bayonet. The Americans inflicted twice the number of casualties on their assailants—an estimated 450 patriots fell as opposed to 1,054 regulars and Royal Marines. The colonist’s valiant defiance imbued them with confidence that they could stand up to the British, while the crown’s losses shook their officers and they often maneuvered prudently to avoid direct assaults against entrenched patriots in subsequent battles.

The first Bunker Hill (CV-17) was authorized under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull 1509) on 19 July 1940; laid down on 15 September 1941, at Quincy, Mass., by the Fore River Shipyard of Bethlehem Steel Co.; launched on 7 December 1942, exactly one year to the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, T.H.; sponsored by Mrs. Lilly W. Boynton, née Case, artist, musician, and leader in Chicago civic affairs, wife of industrialist Donald S. Boynton, and friend of Secretary of the Navy William F. [Frank] Knox; and commissioned on 25 May 1943, Capt. John J. Ballentine in command.

The newly commissioned carrier underwent additional work in Dry Dock No.3, naval dry dock facility, South Boston, Mass. (25 May–5 June). The ship then moved across the harbor to complete fitting-out on the 16th, and five days later on the 21st stood out to train in Massachusetts Bay. Bunker Hill reported to Rear Adm. Patrick N.L. Bellinger, Commander, Air Force, Atlantic Fleet, on 25 June while she headed southward. As the ship approached Hampton Roads, Va., on the 27th the operational planes of Carrier Air Group (CVG) 17 flew out from Naval Air Station (NAS) Norfolk, Va., and introduced themselves to their new home by making a simulated attack against Bunker Hill. The fighters swarmed the ship, followed by the dive bombers and torpedo planes of the group’s other two squadrons.

When the group boarded Bunker Hill the following day the ship loaded 36 Vought F4U-1 Corsairs of Fighting Squadron (VF) 17, Lt. Cmdr. John T. Blackburn in command, 16 Curtiss SB2C-1 Helldivers each of Bombing Squadrons (VBs) 7 and 17, 18 Grumman TBF-1 Avengers of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 17, a single Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat, and one Grumman J2F-2A Duck. The ship marked her first aircraft landings and launchings while she worked up with the embarked air group in Chesapeake Bay (28 June–1 July). Additional training followed, as did refueling, provisioning, and loading ammunition while alternatively at Hampton Roads on the 1st, the next day at Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk, then Chesapeake Bay and the York River on the 5th, and on the 11th back to Hampton Roads. The Navy also established new designations for carriers on 15 July, and the directive limited the previous broadly applied CV symbol to Enterprise (CV-6), Saratoga (CV-3), Ranger (CV-4), and to Essex (CV-9) class aircraft carriers.

Bunker Hill and CVG-17 turned southward for the ship’s shakedown in the Caribbean on that date (15 July–10 August 1943). The carrier anchored at Port of Spain, Trinidad, on the 20th, and took part in exercises in the Gulf of Paria (21 July–6 August), before she swung around for home. The training included shipboard gunnery exercises and carrier qualifications for the pilots. The handling crews on the flight deck and hangar deck honed their skills, and the jeep and tractor drivers discovered new ways of pulling planes under and around the other planes. When Bunker Hill returned to NOB Norfolk she disembarked the air group and that the pilots and the aircrew spent a further three weeks training and perfecting their tactics.

The ship stood out of Norfolk for New England waters, her flight deck conspicuously empty and quiet after the flight operations of the shakedown (11–22 August 1943), and moored at South Boston for a final post-repair overhaul and last-minute additions. Workers and sailors inspected equipment, calibrated the radar, bore-sighted the guns, and greased the flight deck arresting-gear, while working parties brought on board supplies for the long voyage to the Pacific. She then (4–6 September) cleared Boston and steamed for Virginian waters, mooring at Lambert’s Point, Va., on the 5th before mooring at NOB Norfolk.

Bunker Hill embarked CVG-17, comprising 36 F4U-1s of VF-17, 36 SB2C-1s of VB-17, 18 TBF-1s of VT-17, and a lone TBF-1 assigned to the ship, and set out for the Pacific Fleet to fight the Japanese on 8 September 1943. The ship passed down the east coast, crossed the Caribbean, and moored at Cristóbal in the Panama Canal Zone on 16 September. The crew enjoyed a couple of final nights ashore in the Canal Zone, the first with some liberty in Cristóbal. The following day the carrier passed through the canal and entered the Pacific, where the liberty party stormed ashore for a second night when she moored at Balboa. Bunker Hill resumed the voyage on the 18th, and steamed up the western Mexican and Californian coastlines. The vast majority of the crew sailed unaware of their ultimate destination, but Capt. Ballentine announced on the 20th that they were off on their “Glorious Adventure,” but had to make one last stop, and she moored at NAS San Diego on North Island, Calif., on the 26th.

While the ship lay at North Island VF-17 temporarily detached and journeyed to serve with Aircraft, Solomons, in Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides [Vanuatu]. The Americans were just introducing Corsairs operationally, and Navy logisticians determined that getting aircraft parts to an island might prove comparatively easier than attempting to keep pace with the ship’s movements. Bunker Hill used the intervening time to ferry 960 men, which brought the grand total of sailors and marines on board to 2,593 officers and men, along with their 36 Grumman F6F-3 Hellcats of VF-18, 21 F4U-1 and two Eastern FG-1 Corsairs of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 113, 21 F4U-1s, a trio of FG-1s, and a single Eastern FM-1 Wildcat of VMF-422, along with the Seabees of Naval Construction Battalion 92, to Pearl Harbor in the Territory of Hawaii (28 September–2 October). Including the remaining planes of the group from VB-17 and VT-17, aircraft packed the flight deck and the hangar deck. The crowded conditions compelled the ship to curtail operations en route, except for the general quarters alarm which sounded each and every morning an hour before sunrise to keep the crew sharp and alert. The aircraft from the other three ferried squadrons went ashore at various stations, while those of the air group went to NAS Kaneohe Bay. Bunker Hill joined Task Groups (TGs) 59.13 and 19.15 for exercises (6–9 and 17–19 October, respectively) to further prepare for war.

By 21 October 1943, CVG-17 assumed ship-based status, and as part of TG 53.3, Bunker Hill got underway to the South Pacific for fleet tactical exercises. Initiating neophytes into the Order of Shellbacks into King Neptune’s Court on 26 October enlivened the various drills and drab routine of duties. When the ship anchored at Palikulo Bay at Espíritu Santo on 5 November, the task organization changed, and Bunker Hill joined Rear Adm. Alfred E. Montgomery’s Southern Carrier Group. The change occurred because of the newly organized Fast Carrier Task Force, TF 50, Rear Adm. Charles A. Pownall in command, four task groups that contained a powerful concentration of carriers. Pownall served double-hatted as he also led the Carrier Interceptor Group (TG 50.1), built around Lexington (CV-16), Yorktown (CV-10), and small aircraft carrier Cowpens (CVL-25). The Northern Carrier Group (TG 50.2), Rear Adm. Arthur W. Radford, numbered Enterprise (CV-6), Belleau Wood (CVL-24), and Monterey (CVL-26). The Southern Carrier Group (TG 50.3), Rear Adm. Montgomery, fought with Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence (CV-22). The Relief Carrier Group (TG 50.4), Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman, sailed to war with Saratoga (CV-3), with CVG-12 embarked, and Princeton (CVL-23).

While the first two groups took part in operations across the Central Pacific, the latter two groups steamed in the South Pacific for Operation Cartwheel, the Allied plan to advance toward Rabaul, on New Britain in the Bismarcks. The Japanese had overrun the islands and heavily fortified and garrisoned them, in particular, turning Rabaul and its environs into a veritable fortress. Cartwheel consisted of different phases including Operation Cherryblossom—landings by the 3rd Marine Division, Maj. Gen. Allen H. Turnage, USMC, of the I Marine Amphibious Corps, Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, USMC, at Cape Torokina near Empress Augusta Bay, Bougainville, in the Australian Territory of New Guinea, on 1 November 1943. Rear Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson led the III Amphibious Force that landed and supported the marines. Aircraft, Solomons, including the Thirteenth Air Force, naval, marine, and Royal New Zealand Air Force planes struck enemy airfields, vessels, and troops across the region in the days preceding the landings. Fifth Air Force aircraft also flew strikes from their fields in Australia, primarily against targets around Rabaul. The cruisers and destroyers of TF 39, Rear Adm. Aaron S. Merrill, shelled targets in the area, and later bombarded Japanese airfields on Shortland Island in the Solomons. The enemy returned fire and damaged destroyer Dyson (DD-572), and one of their planes hurt Wadsworth (DD-516) by a near-miss with a bomb.

In addition, Sherman directed Saratoga and Princeton to launch their planes against Japanese airfields and installations in the Northern Solomons at Buka, which lies across the Buka Strait from Bougainville, and against Bonis on the peninsula of the same name on Bougainville, on the 1st. The admiral and his staff intended for the raids to diminish Japanese aerial resistance against the landings at Cape Torokina. The attackers took off before dawn, which resulted in considerable confusion and delays in effecting their rendezvous, but they struck the enemy determinedly. A Combat Air Patrol (CAP) averaging 38 fighters in the meantime rotated over the beaches and disrupted major Japanese aerial counterattacks. The Americans claimed to splash or damaged 33 Japanese aircraft, and to sink or damage nine cargo ships, 11 barges, and other coastal craft, while losing three planes.

Rear Adm. Ōmori Sentarō led a Japanese force of two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and six destroyers that attempted to counterattack the transports off Bougainville. Merrill took four light cruisers and eight destroyers and intercepted and turned back Ōmori during the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay on the night of 1 and 2 November 1943. Japanese 8-inch gunfire damaged light cruiser Denver (CL-58); a torpedo punched into Foote (DD-511); and enemy gunfire and a collision damaged Spence (DD-512) and Thatcher (DD-514). Charles Ausburne (DD-570), Claxton (DD-571), Dyson, Spence, and Stanly (DD-478) sank Japanese destroyer Hatsukaze, which also collided with heavy cruiser Myōkō; and U.S. gunfire sank light cruiser Sendai and damaged heavy cruisers Haguro and Myōkō. In addition, destroyers Samidare and Shiratsuyu collided during the night surface action. Enemy planes attacked the U.S. ships as they retired and damaged Montpelier (CL-57), but the preliminary air strikes the previous day prevented the Japanese from counterattacking decisively. Sherman followed suit after the Japanese aerial attacks and launched planes for a second (planned) strike on Buka.

In addition on the following day, Saratoga and Princeton sent two coordinated strikes against the enemy airfields. Planes from Princeton bombed and strafed antiaircraft positions at Bonis, cut down a number of Japanese soldiers, and set fire to barrels of aviation gasoline stored along the edges of the runway. Hellcats furthermore strafed a couple of cargo ships. The enemy fought back fiercely and threw up heavy antiaircraft fire, largely from 13.2 and 20 millimeter guns. The Japanese sought to prevent the Allies from establishing their air power on Bougainville, and continued to concentrate cruisers and destroyers of the Second Fleet, Rear Adm. Takagi Takeo, in Simpson Harbor at Rabaul. On only 14 hours’ notice, Sherman led Saratoga, Princeton, and their screen northward to attack the fleet, at one point taking advantage of foul weather to cloak their approach. On the morning of 5 November 1943, the carriers launched their aircraft from a position about 220 miles south-southeast of Rabaul against the vessels in Simpson Harbor.

“As our planes approached,” VF-23’s historian reflected, “the harbor was protected by an umbrella of terrific anti-aircraft fire, the likes of which our boys had never experienced before, and hope never to see again. Japanese fighter planes swarmed the sky, Zekes [Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 carrier fighters], Tonys [Kawasaki Ki-61 Hiens], Hamps [A6M3-32s]—everything the enemy could get airborne.” The U.S. carrier planes damaged heavy cruisers Atago, Chikuma, Maya, Mogami, and Takao, light cruisers Agano and Noshiro, and destroyers Amagiri and Fujinami. The battle exhausted the surviving aircrewmen, and Sherman ordered the ships to come about and make speed to the southward to be within range of Allied shore based fighters. The results pleased Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., Commander South Pacific Area, but the surviving Japanese ships at Rabaul continued to threaten the Allies and so he resolved to launch another attack.

Bunker Hill readied to join the fighting as she anchored in Palikulo Bay (5–7 November 1943). News of the strikes circulated among the “scuttlebutt” (rumors) on board Bunker Hill and the following day, while the carrier and her consorts steamed as TG 50.3.1 toward what many men thought would be the area of Bougainville to join the fighting there, the pilots and crews of CVG-17 attended briefings to ready themselves to carry out Operation Plan 16-E-43—an attack against Rabaul. On the 9th her embarked air group counted 32 F6F-3s of VF-18, 33 SB2C-1s of VB-17, 18 TBF-1Cs of VT-17, and a lone TBF-1C assigned to the ship (and Montgomery). “On the night [the 10th] before the attack we were fed a big dinner,” Frank Petriello of Bunker Hill’s ship’s company remembered. “The chaplain offered benediction on the PA system. I had the feeling it was like the condemned man getting his last meal.” The next morning dawned ironically on Armistice Day, 11 November 1943, as the squadrons from Bunker Hill entered the war in earnest.

Saratoga and Princeton operated to the east as they launched their planes first during the forenoon watch beginning at 0830. Low clouds reduced visibility and impeded their strike but they bore in on their foes. Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence steamed to the southeastward as they sent the first of their aircraft aloft an hour later. Some dozen Hellcats and 24 Corsairs flew from ashore as CAP over Montgomery’s ships, enabling him to launch most of his operational aircraft. The weather continued to interfere with the raiders and they inflicted only minimal damage, though they claimed to splash 24 planes while losing seven of their own, and sank destroyer Suzunami, and damaged light cruisers Agano and Yūbari, and destroyers Naganami, Urakaze, and Wakatsuki. The stark weather compelled Sherman to cancel a second wave, but Montgomery recovered, refueled, and rearmed the first wave and prepared to send them out again at 1325.

The Japanese retaliated with a huge strike of their own and threw more than 100 aircraft against the Southern Carrier Group. Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence steamed with their flight decks crammed with aircraft and appeared to be vulnerable but unbeknownst to the Japanese, the U.S. ships tracked the inbound planes on their radar and dispatched their CAP, both the fighters from ashore, and those freshly refueled and armed. The fighters ripped into the enemy and the carriers and their escorts fired a devastating antiaircraft barrage that accounted for destroying an estimated 40 enemy planes for the loss of 11. The land-based Hellcats and Corsairs splashed an entire attack group of 14 Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 carrier attack planes (Kates), and then landed on the carriers to refuel and rearm, before they returned to the fierce fighting. The combination of the radar, fighters, and gunfire ensured that the enemy failed to hit a single ship.

The battle witnessed the introduction to combat of the Helldivers from VB-17. Furthermore, Hispanic pilot Lt. (j.g.) Eugene A. Valencia, USNR, of VF-9 flew an F6F-3 Hellcat from Essex and shot down a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 carrier fighter over Rabaul. Valencia scored 23 confirmed victories during WWII and his decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross. According to Glen A. Boren, who against regulations kept a diary of his experiences as a sailor on board Bunker Hill throughout the war, the Hellcat pilots of VF-18, “made a score of 18 dive bombers and four torpedo planes and 12 Zeros. Our pilots made a wonderful showing for the first time in action. The men had only 2 months of training in the F6F and very little gunnery.” Bunker Hill’s gun crews accounted for six of these planes with other “possibles.”

Bunker Hill’s entry into the war included VF-17 flying CAP for the task group as the air group’s fighters accompanied the bombers and torpedo planes to the target. Ens. Ira C. Kepford, USNR, once confined to quarters for ten days for mock dogfighting a USAAF North American P-51 Mustang above the city of Norfolk, received the Navy Cross for the battle on 11 November 1943 when he shot down three Aichi D3A1 Type 99 carrier bombers (Vals) and one Kate. He would survive the war as an ace with 16 victories. The squadron received credit for destroying 28.5 Japanese airplanes and damaging 18 others.

The battle also marked the increased use of new but untried impulse ammunition, known as the VT 5-inch/38 cal. type Mk. 32. When ships of TF 67 bombarded Japanese positions in Munda on New Georgia in the Solomons on 5 January 1943, Japanese planes counterattacked the force. A dive bomber attacked Helena (CL-50) but she splashed the attacker with a proximity fuzed projectile in the second salvo from her 5-inch guns off the south coast of Guadalcanal. The ammunition made its appearance with the 5-inch gun crews on board Bunker Hill and proved to be the answer to enemy dive-bombing attacks.

Adm. Halsey wrote a (second) endorsement letter on 12 November 1943 to Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, however, concerning the Report of Action on the 11th. The letter disagreed with Boren’s account in regards to VT-17. Halsey “does not fully concur,” the admiral said, with the torpedo squadron’s performance and that it “must be classed as poor,” and that “mal-functioning of torpedo releasing gear and erratic torpedo performance appear to have combined to produce disheartening results.” Rear Adm. Montgomery received orders to immediately investigate the material condition and state of training of the torpedo squadron, specifically to ascertain whether Mk-8 detonators were installed, and whether adaptive countermeasure devices were rendered inoperative. Halsey did note the “creditable performance” of Bunker Hill in repelling “her first heavy air attack.” The raid all but eliminated any major threat to the landings on Cape Torokina, and helped to secure the extended Allied supply lines in the region.

Following the raids the group refueled at Palikulo Bay on 14 November 1943, and still as TG 50.3.1 stood out the next day for Nauru, the westernmost of the Gilbert Islands [Kiribati]. Pownall led TF 50 in two days (18–19 November) of air attacks on the Japanese in the Gilbert group during Operation Galvanic—the occupation of those islands. Bunker Hill, Enterprise (CV-6), Essex, Lexington, Saratoga, Yorktown, Belleau Wood, Cowpens, Independence, Monterey (CVL-26), and Princeton comprised the main carriers. Eight escort carriers, Barnes (CVE-20), Chenango (CVE-28), Coral Sea (CVE-57), Corregidor (CVE-58), Liscome Bay (CVE-56), Nassau (CVE-16), Sangamon (CVE-26), and Suwanee (CVE-27), covered the approach of the assault shipping and the landings. Bunker Hill rendezvoused with the rest of TG 50.3 on the 15th–16th to fight under the auspices of Operation Plan 53-43.

While Pownall struck those targets, Sherman’s TG 50.4 attacked Nauru in support. Princeton and her consorts refueled at a position not far from Nanomea and then steamed northeast, and covered the garrison groups while they steamed en route to Makin and Tarawa. The carriers then (on the 19th) launched three strikes that blasted the islands and crated the runways, rendering them unserviceable. In the all-day attack, Princeton’s Hellcats splashed two Japanese fighters that attempted to interfere with the air coverage.

Bunker Hill in the meantime supported the V Amphibious Corps, comprising the 2nd Marine Division and soldiers of the 27th Infantry Division, when they landed against bitter Japanese resistance on Tarawa, and on Abemama and Makin Atolls. While Allied cruisers and other warships shelled Betio [Bititu Island] at Tarawa in a pre-invasion shelling to soften up the island defenses on 17 November 1943, Bunker Hill steamed with the rest of the Southern Carrier Group in an attempt to lure the Japanese fleet from their stronghold at Truk in the Caroline Islands. Air and surface bombardments of Betio commenced as ground troops assaulted Tarawa.

At dawn on 18 November 1943, planes flying from Bunker Hill began to pound Japanese dugouts, gun emplacements, and shore installations. Bunker Hill’s airmen furnished such call support as they could as the marines stormed ashore in the horrific battle. At nightfall, 16 enemy torpedo bombers assailed the invasion fleet. The fighters of the CAP intercepted and claimed to splash at least four of the bombers, but nine broke through and assailed Montgomery’s carriers, three toward Bunker Hill and Essex, and six against Independence. Bunker Hill opened fire and claimed six of the assailants, and a destroyer downed another (five confirmed in total). One of the enemy planes dropped a torpedo that punched into Independence, killing 17 men and wounding 43 more, and the carrier retired from the battle to lick her wounds.

Lt. (j.g.) Armand G. Manson, USNR, of VF-18 made the 4,000th landing on board Bunker Hill on 23 November. On the 24th Japanese submarine I-175 torpedoed and sank Liscome Bay 20 miles southwest of Butaritari Island, killing 645 men—272 men survived. The submarine escaped. Through that date aircraft flew 2,278 close support, CAP, and antisubmarine sorties, and dropped 203.5 tons of bombs on enemy targets with very few casualties or losses to the planes or airmen. The F6F-3 Hellcats of VF-1 from Barnes and Nassau landed on the airstrip at Tarawa as the first planes of the garrison air force on the 25th. Once the marines secured the islands a carrier group remained in the area for an additional week as a protective measure. Bunker Hill came about from the Battle of Tarawa as she detached from TG 50.3 and joined TG 50.4 as Flagship Gilberts on the 26th to cover the fighting on Makin.

Until December 1943, Bunker Hill patrolled the area around the Gilberts accompanied by battleships while forces on shore converted the islands into American base. Rear Adm. Willis A. Lee swung back southward toward further action in the Solomons, and planes from Bunker Hill’s CVG-17 and Monterey’s CVG-30 screened his five battleships, Alabama (BB-60), Indiana (BB-58), North Carolina (BB-55), South Dakota (BB-57), and Washington (BB-56), and a dozen destroyers during the voyage. Along the way, Lee hurled another air and naval gunfire strike against enemy-held Nauru on 8 December 1943. The Japanese deployed few aircraft on the island and the raiders achieved meager results, claiming the destruction of at least eight planes while losing four. Vought OS2U-3 and Naval Aircraft Factory OS2N-1 Kingfishers from Observation Squadrons (VOs) 6 and 9, embarked on board the battleships strafed and photographed the area around the barracks when the ships ceased fire. A shore battery hit Boyd (DD-544) while she rescued some downed aviators and she came about for repairs.

Bunker Hill arrived back at Espíritu Santo for some rest and relaxation on 12 December, although the island weather proved less than ideal with great amounts of both rain and resulting mud. The air group made the ship’s company jealous when they received permission to fly to Bomber Field No. 3 on the island to spend ten days living on the beach, and then flying back to the ship for meals while exclaiming the food ashore was terrible. Tons of mail from home finally caught up with the crew, and the men appreciated the short-lived break from the war. Capt. Conrad E. Ekstrom, the executive officer, was detached on 15 December 1943 and ordered to the U.S. for pre-commissioning duty with an escort carrier detail. Cmdr. Charles A. Ferriter, who had received the Navy Cross for “extraordinary heroism and distinguished service” while in command of minesweeper Whippoorwill (AM-35) in the Philippines, relieved Ekstrom. When the Japanese bombed the Cavite Navy Yard on 10 December 1941, Ferriter disregarded the falling bombs, exploding ordnance, and burning fuel and “displayed extraordinary courage and determination in proceeding into the danger zone and towing disabled surface craft alongside docks to a safe zone. This prompt and daring action undoubtedly saved the crews from serious danger and saved the vessels for further war service.” Ferriter in particular took Peary (DD-226) in tow as the flames touched off a catastrophic explosion of torpedo warheads in an overhaul shop.

The ship and her air group prepared for more fighting and the group numbered 39 F6F-3s of VF-18, 33 SB2C-1s of VB-17, 18 TBF-1Cs of VT-17, and one flag TBF-1C on the 21st. The following day Bunker Hill joined the Third Fleet and acted as flagship for TG 37.2 when she cleared the harbor for what were to be a series of raids against Japanese shipping at Kavieng, New Ireland. The Japanese also overrun the island as part of their conquest of Rabaul and fortified and garrisoned it, though not as strongly as Rabaul. The Allies nonetheless decided to attack the port as part of their plan to isolate the Japanese forces in the region, and to cover Operation Backhander—marine landings scheduled for the following day on Cape Gloucester, New Britain. Christmas thus brought Bunker Hill’s crew no holiday cheer as they found themselves deeper within enemy territory as part of Operation Plan 19-43 TG 37.2’s Operations Order 2-43. The ship launched her air group’s planes against the enemy, and the U.S. pilots noticed early-on that their Japanese counterparts did not appear as determined to engage them as they once had been, leading to few dogfights. Letting their guard down also led to maximum damage inflicted against enemy harbor shipping, and in spite of heavy antiaircraft fire planes sank Japanese transport Tenryu Maru, and damaged minesweepers W.21 and W.22 and transport (ex-armed merchant cruiser) Kiyozumi Maru. Only then did the Japanese pilots fight back, and some Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 attack planes (Bettys) half-heartedly pursued the American ships, which escaped unscathed.

The lack of strong enemy resistance and the need to further support the fighting on Cape Gloucester led Halsey to order the ships to raid Kavieng again. The directive reached the vessels of the task group as they steamed halfway back to base but they swung around for a second raid on the harbor. New intelligence indicated that the raid concerned the Japanese and they decided to reinforce their garrison on New Ireland. Light cruisers Noshiro and Oyodo, and destroyers Akikaze and Yamagumo, sailed from Truk for Operation BO-3—transporting approximately 600 men of the 51st Infantry Battalion, 1st Mixed Independent Regiment, and nearly 1,500 tons of ammunition and equipment (30 December 1943–1 January 1944).

Bunker Hill counted 36 F6F-3s of VF-18, 23 SB2C-1s of VB-17, 15 TBF-1Cs and five TBF-1s of VT-17, and a lone TBF-1C, while Monterey sailed with 23 F6F-3s of VF-30 and three TBF-1Cs and five TBF-1s of VT-30 as they approached the New Year of 1944. On the morning of 1 January they launched their aircraft against the Japanese, who detected them at 0827 and sounded the alert and their ships prepared to sortie. This time therefore, the enemy fighters rose to offer stiffer air resistance and met the attackers in a determined clash in the skies above Kavieng when the latter swept in at 0842. The Japanese ships threw up a huge volume of antiaircraft fire, and Noshiro alone shot 63 5.9–inch, 29 3-inch, and 1,612 25 and 13.2 millimeter rounds. Despite the loss of two Hellcats and a bomber the attackers claimed to splash 14 enemy aircraft and damage another dozen. A carrier plane also dropped a bomb that struck Noshiro on her starboard side and knocked out the No. 2 turret. A second bomb splashed into the water off the starboard bow and narrowly missed the cruiser, but the concussion caused flooding in the forward powder magazine. The attack killed ten of Noshiro’s crewmen and she departed in company with Oyodo and Yamagumo for repairs at Truk, which they reached the following day.

The U.S. ships retired only to receive Halsey’s orders for a third strike against Kavieng. Bunker Hill and Monterey refueled and turned their prows yet again toward New Ireland. The carriers launched their raiders on 4 January 1944, and when the American and Japanese planes tangled above the now familiar port the former only claimed to splash two of the latter. The enemy aircraft lunged vengefully for the ships but the CAP splashed several as the task group came about without any damage to the ships. The trio of raids further weakened the enemy in the area after the fighting at Rabaul and the Allies subsequently bypassed them in their advance on the Japanese home islands.

The task group charted course for the Central Pacific and Bunker Hill anchored in Segond Channel at Espíritu Santo while the group flew ashore to Lugan Airfield (7–19 January 1944), and she then (19–20 January) moved and anchored in the lagoon at Funafuti in the Ellice Islands [Tuvalu]. The carrier shifted to TF 58, Rear Adm. Mitscher, and five days later to TG 58.3. The F6F-3Ns of Night Fighting Squadron (VF(N) 76, equipped with AN/APS-6 radar for their deadly work, detached from Essex and landed on board Bunker Hill on the 25th, before Essex fueled and stood out to attack the Japanese garrisons of Kwajalein, Maloelap, and Wotje during Operation Flintlock—the occupation of the Marshall Islands. The Allies needed the Marshalls to provide bases for the forthcoming assaults on the Marianas and the eventual liberation of the Philippines. Mitscher commanded a vast assemblage of carriers including Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Essex, Intrepid (CV-11), Saratoga, Yorktown, Belleau Wood, Cabot (CVL-28), Cowpens, Langley (CVL-27), Monterey, and Princeton. Land-based planes of TF 57, Rear Adm. John H. Hoover, also supported the landings. Bunker Hill fueled southwest of Jaluit Atoll in the Marshalls on the 28th as she steamed toward the battle.

The carriers launched their first strikes on 29 January, D-Day minus two. Aircraft from eight escort carriers flew cover and antisubmarine patrols, and scout planes assisted naval bombardments. Bunker Hill’s planes hit Kwajalein and Ebeye Islands while she steamed north to Eniwetok Atoll to rain destruction on Japanese airfields. On the 30th Hellcats and Douglas SBD-5 Dauntlesses from TG 52.8, comprising Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Yorktown, and Belleau Wood sank Japanese auxiliary submarine chasers Cha 18 and Cha 21 at Kwajalein; auxiliary submarine chasers Cha 14, Cha 19, and Cha 28 at Mili; and damaged cargo vessel Katsura Maru at Eniwetok. Phelps (DD-360) subsequently finished off the crippled enemy merchantman.

The ship considered the operation a complete success despite the sacrifice and loss of 13 members of Bunker Hill’s valiant air group. The raids wiped-out the Japanese air strength on the islands. Raymond Clapper, famed commentator and news analyst, embarked on board Bunker Hill to report on the battle. The journalist untiringly went aloft as a passenger in one of the ship’s planes in order to better view the landings. As the aircraft joined up following the strike, his plane collided with a second, and both spiraled into the water, killing Clapper and all the other airmen.

Due to the curious sequence of coincidences in which Bunker Hill conducted missions against the enemy on every major holiday, she facetiously earned the nickname “The Holiday Express,” from news correspondents often hitching a ride to report from the front. The list of holiday raids was impressive: New Britain on Armistice Day 1943; Tarawa on Thanksgiving Day 1943; the Christmas Day 1943 attack on Kavieng, New Ireland; the second strike against Kavieng on New Year’s Day 1944; and a raid on the Marshall Islands on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s birthday on 30 January 1944.

Marines and soldiers landed on islands at Kwajalein and Majuro on 31 January 1944. Into the first three days of February planes from TG 58.3, Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman, bombed Japanese aircraft and airfields at Engebi Island at Eniwetok. Through 7 February TG 58.4, Rear Adm. Samuel P. Ginder, later supplemented Sherman. Additional landings occurred on Kwajalein, Namur, and Roi on the 1st of February.

The ship anchored in Majuro on 5 February 1944, where Capt. John J. Ballentine was promoted to rear admiral, and received the Silver Star and Legion of Merit for “daring and skillful leadership of a carrier flagship in the South Pacific.” Capt. Thomas B. Jeter, the former exec and navigator of Enterprise, relieved Ballentine on that eventful day. Several days later, beginning on the morning of 16 February, Capt. Jeter learned that his first mission as commanding officer would be to assault Truk in Operation Hailstone—one of the covering operations for the liberation of the Marshalls. The ship fought under Operation Plan 2-44 while part of TG 58.3. While en route, the crew became spooked when a fighter flying CAP splashed an enemy patrol plane, possibly meaning there might be others around and that the element of surprise could be lost. The Americans attained tactical surprise on 17 February 1944, however, and their planes destroyed Japanese shore installations and filled the lagoon with smoking and fast-sinking ships.

During the two-day attack Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, whose forces included TF 58, launched 1,250 combat sorties that dropped 400 tons of bombs and torpedoes, and battleships and cruisers added to the destruction as they unleashed their guns against the enemy as the attackers sank 37 Japanese ships aggregating 200,000 tons and damaged installations. The vessels sunk included light cruiser Naka, training cruiser Katori, destroyers Fumizuki, Maikaze, Oite, and Tachikaze, armed merchant cruiser Akagi Maru, auxiliary submarine depot ship Heian Maru, submarine chasers Ch 24 and Ch 29, aircraft transport Fujikawa Maru, minesweeper Shonan Maru No. 15, transports Aikoku Maru, Amagisan Maru, Gosei Maru, Hanakawa Maru, Hokuyo Maru, Kensho Maru, Kiyozumi Maru, Matsutani Maru, Momokawa Maru, No. 6 Unkai Maru, Reiyo Maru, Rio de Janeiro Maru, San Francisco Maru, Seiko Maru, Taihō Maru, Yamagiri Maru, and Zukai Maru, fleet tankers Fujisan Maru, Hoyo Maru, No. 3 Tonan Maru, and Shinkoku Maru, water carrier Nippo Maru, auxiliary vessel Yamakisan Maru, army cargo ships Nagano Maru and Yubai Maru, merchant cargo ship Taikichi Maru, and motor torpedo boat Gyoraitei No. 10.

Three waves of Helldivers and Avengers of VB-17 and VT-17, and TBF-1Cs of VT-25 flying from Cowpens, swarmed Naka as she attempted to escape from Truk. The ship dodged the attackers’ first two waves but the planes of the third wave dropped a torpedo and a bomb that both slammed into the cruiser and she broke in half and sank, taking 240 men with her about 35 miles west of the lagoon. Akagi Maru and her escorts, Katori, Maikaze, Nowaki, and Shonan Maru No. 15, attempted to slip out of Truk and make for home at Yokosuka during the morning watch, but aircraft from Bunker Hill, Intrepid, Yorktown, and Cowpens worked over the convoy and sank the armed merchant cruiser, torpedoed and strafed the training cruiser, and shot up Maikaze. Iowa (BB-61), New Jersey (BB-62), heavy cruisers Minneapolis (CA-36) and New Orleans (CA-32), and Burns (DD-588) and Radford (DD-446) blasted the escapees with their heavy salvoes and finished off Katori, Maizake, and Shonan Maru No. 15 northwest of Truk. Nowaki fled and survived. Burns detached from TG 50.9 and sank submarine chaser Ch 24 west of Truk.

Hailstone eliminated enemy surface resistance from Truk, but Bunker Hill paid a steep price for the victory. Antiaircraft fire killed Lt. (j.g.) George L. Glass, a Helldiver pilot with VB-17 (BuNo 00093), and his radioman ARM2c Claude W. Aunspaugh, when they attacked an enemy supply ship and the Helldiver crashed into Truk Lagoon and exploded. Twelve radar-equipped TBF-1C Avengers from VT-10, embarked on board Enterprise, carried out the first U.S. carrier-launched night bombing raid and scored several hits on ships in the lagoon. Night fighter detachments of F6F-3N Hellcats and F4U-2N Corsairs fitted with AN/APS-6 radar from VF(N)s 76 and 101 operated from four carriers, four of the specially equipped Hellcats on board Bunker Hill, and on occasion were vectored against enemy night raiders. The first night a Japanese aerial torpedo struck Intrepid, but despite steering problems Intrepid returned for repairs to Pearl Harbor. The very next day pilots pressed home the strikes again, but the devastating attacks of the previous day left few targets. Still, Lt. (j.g.) Newton B. Birkes, AOM2c Frederick S. McKenzie, and AMM3c Stanley S. Stump of VT-17 were declared missing in action when their TBF-1C (BuNo 47812) failed to return to Bunker Hill.

On 19 February 1944, Bunker Hill received Operation Plan 3-44 and on the 22nd responded to the directive and turned toward Tinian in the Marianas. Ens. Robert W. Bice, a pilot with VF(N)-76, made four strafing runs on a Japanese airfield but became separated from the other members of his squadron. All returned to Bunker Hill except for Bice and Ens. Jack R. Bertie. Despite wounds in his left arm and leg, Bertie engaged in a dogfight with enemy fighters over Tinian and claimed to shoot down three Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 carrier fighter (Zeros). In pain the entire way back to the carriers, he managed to land on board Essex. He also related a story about seeing Ens. Bice abreast of him during the last strafing run. Bertie then recalled he was “suddenly in the middle of a number of Zeros,” and stated he believed Bice was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. The battle marked Bice’s first, and last, mission.

The carriers launched raids on Japanese vessels in Tanapag harbor at Saipan in the Marianas on the 23rd. F6F-3s of VFs 9 and 5, SBD-5s of VBs 9 and 5, and TBF-1, TBF-1C, and TBM-1Cs of VTs 9 and 5 from Essex and Yorktown (in TG 58.2), respectively, damaged cargo ship Shoan Maru; and planes from Bunker Hill sank cargo vessel Seizan Maru off Tinian. Planners specifically chose Tinian to eliminate further bases from which the Japanese could resist and which the U.S. could soften the Japanese home islands up for a final invasion. Aircraft flew through weak air resistance and easily shot up targets on the ground almost at will. Nonetheless, the action did not pass without casualties, and the loss of one pilot shot down and one missing weighed heavily on the men.

Bunker Hill turned eastward for Hawaiian waters (28 February–4 March 1944), and completed voyage repairs and upkeep while in dry dock at Pearl Harbor Navy Yard (6–9 March). The air group detached while their carrier accomplished the work, and VF(N)-76 did so temporarily to Ford Island. War Correspondents Davis J. Beaufort, Spencer Davis, and W. Eugene Smith left the ship, and Smith would continue on as an acclaimed photographer despite being wounded on Okinawa in the Ryūkyū Islands. The ship wrapped-up the yard work and, sans CVG-17, landed a new air group, CVG-8, which flew on from NAS Pu'unene, Maui, T.H. Four night fighting Hellcats of VF(N)-76 also joined the carrier, and she then (15–20 March) steamed for Majuro under Movement Order 2-44. The day after Bunker Hill anchored in the atoll, CVG-8 reported 41 F6F-3s of VF-8, 32 SB2C-1Cs of VB-8, 22 TBF-1Cs of VT-8, and a flag F6F-3 on board, along with the four F6F-3Ns.

Mitscher took TF 58, including 11 carriers, back to sea again for Operation Desecrate I—a series of attacks on Japanese garrisons and vessels at Palau, Ulithi, Woleai, and Yap in the Western Carolines (30–31 March 1944), just east of Mindanao in the Philippines. Planners intended for these strikes to eliminate Japanese opposition to landings at Hollandia on northern New Guinea and to gather photographic intelligence for future battles. The increasingly seasoned Bunker Hill cleared the atoll on the 22nd under Operation Order 4-44 as part of TG 58.2 and made for the Carolines once again. Bunker Hill’s directive aimed her toward Palau, the westernmost of the Caroline Group. The TBF-1C and TBM-1C Avengers of VTs 2, 8, and 16 flying from Bunker Hill, Hornet (CV-12), and Lexington, sowed extensive minefields in the approaches to the Palaus in the first U.S. large scale daylight tactical use of mines by carrier aircraft. In two days of operations, Bunker Hill’s Hellcats claimed to splash 11 enemy planes and destroyed several others on the ground.

As the ships retired eastward they launched raids against Woleai on April Fool’s Day 1944. The attackers encountered light resistance both in the air and on the ground and worked over the defenders. Ens. John R. Galvin, USNR, flying a Hellcat (BuNo 40695) from VF-8 off Bunker Hill, bailed out of his damaged plane just a short distance from the target. Rescued by a friendly ship when the crew put a rubber raft over the side, he then helped hold off a Japanese attempt to capture him by firing on the enemy and forcing them back. Ens. Warner W. Delesdernier’s Hellcat (BuNo 25824) was also shot down over Woleai. The rescuers failed to find him and he was declared missing in action shortly after.

These raids continued through 1 April 1944 and altogether claimed to destroy 157 Japanese aircraft, and wreaked havoc with the enemy vessels trapped within the atoll and sank destroyer Wakatake; aircraft transport Goshu Maru; submarine chaser Ch 6; auxiliary submarine chasers Cha 22, Cha 26, Cha 53, and No. 5 Showa Maru; Patrol Boat No. 31; netlayer No. 5 Nissho Maru; fleet tankers Akebono Maru, Amatsu Maru, Iro, Ose, and Sata; tankers Amatsu Maru and Asashio Maru; transports Gozan Maru, Nagisan Maru, No. 18 Shinsei Maru, Raizan Maru, and Ryuko Maru; guardboats Ibaraki Maru and No. 2 Seiei Maru; repair ship Akashi; salvage vessel Urakami Maru; torpedo transport and repair ship Kamikaze Maru; army cargo ships Chuyo Maru, Kibi Maru, and Shoei Maru; army tanker No. 2 Unyo Maru; and army cargo ships Bichu Maru (outside Palau harbor) and Teisho Maru (in the channel west of Palau), and, at Angaur, small craft Akebono Maru, Chichibu Maru, Hinode Maru, Kiku Maru, No. 3 Akita Maru, Toku Maru, Ume Maru, Yae Maru, and Yamato Maru. In addition, TF 58 planes damaged submarine chaser Ch 35, netlayer Shosei Maru, tanker No. 2 Hishi Maru, and army cargo ship Hokutai Maru at Palau. The devastation from the raiders and the minefields denied the harbor to the enemy for an estimated six weeks. Allied submarines and aircraft made great efforts to rescue downed pilots and aircrewmen, which boosted their morale and thus effectiveness, and although the Americans lost 25 planes, submarines, including Harder (SS-257), rescued 26 of 44 airmen.

Bunker Hill returned to Majuro and anchored in the atoll (6–13 April 1944) as she prepared to sail with Vice Adm. Mitscher and TF 58 to support the assault of the Army’s I Corps at Aitape and Tanahmerah Bay (Operation Persecution) and at Humboldt Bay on Hollandia (Operation Reckless) on the north coast of New Guinea. The ship fought again as part of TG 58.2, this time under Operation Order 5-44. The balance of the attack force rendezvoused northwest of Manus in the Admiralty Islands early on the 20th. They encountered excellent visibility with a clear sky and no moon on 21 April until about 0300, when a squall overtook the formation from directly astern and reduced visibility to several hundred yards. The bad weather dogged them until just before 0436, at which time Covering Force Baker (Fire Support Group Charlie), TG 75.3, of the Central Attack Group, detached for their assigned fire support area. Five heavy and seven light carriers launched preliminary strikes on Japanese airfields around Hollandia, Sawar, and Wakde.

The following day the carriers covered landings at Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay, and Humboldt Bay. A possible submarine sound contact compelled the ships to urgently maneuver at various courses and speeds until the sonar teams evaluated the echoes as false. Phoenix (CL-46) logged the weather on 22 April as “intermittently squally’, but added triumphantly that “while still as much as 40 miles from our objective, the glare of a fire was visible against the sky, apparently a memento of our recent bombing attacks.” Aircraft sank Japanese army cargo ship Kansei Maru off Sarmi, and Navy planes sent small cargo vessels No. 2 Hihode Maru and No. 51 Ume Maru to the bottom off Mapia Island. Of all the missions flown by Bunker Hill’s air squadrons only one successfully resulted in the sinking of an enemy cargo ship. The landings secured their beachheads and Hollandia became a major staging area for the next phase of the New Guinea campaign. Bunker Hill returned to Majuro to get ready for her next endeavor.

The ship received Operation Order 6-44 by dispatch on the 27th, and then cleared the atoll to join the task force when it again visited Truk with devastating power (29–30 April). Planes attacked Japanese shipping, oil and ammunition dumps, aircraft facilities, and other installations. Enemy naval aircraft fiercely counterattacked the U.S. formations, and once again the fighters of the CAP intercepted the attackers, only 25 miles from the ships. A few managed to break through, but caused no damage to Bunker Hill, though friendly fire damaged Tingey (DD-539) in TG 58.2. Bunker Hill lost a rare fighter from VF(N)-76 on 22 May when Lt. (j.g.) Julian Jolliff, piloting his Hellcat (BuNo 26104) over Majuro, was shot down and declared missing in action shortly after. The ship anchored in Majuro (4–21 May), and then (21–23 May) trained at sea with TG 58.2.5 before returning to the anchorage.

Following that all too fleeting break, Bunker Hill set out with TG 58.3 to support Operation Forager—the invasion of the Marianas. Mitscher led TF 58, which included Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Essex, Hornet, Lexington, Wasp (CV-18), Yorktown, Bataan, Belleau Wood, Cabot, Cowpens, Langley, Monterey, Princeton, and San Jacinto. The Americans began the assault by landing on Saipan. The carriers sent their first fighter sweeps against the island on 11 June and continued for the next three days. Mitscher threw additional strikes against the Japanese garrison on Saipan 13 June. On that date, Bunker Hill’s CVG-8 reported 37 F6F-3s of VF-8, 33 SB2C-1Cs of VB-8, 13 TBF-1Cs and five TBM-1Cs of VT-8, a flag F6F-3, and four F6F-3Ns of VF(N)-76 on board. American carrier planes sank aircraft transport Keiyo Maru, which had been damaged in the fighter sweep on 11 June, and annihilated a convoy of small cargo vessels and sank Myogawa Maru, No. 11 Shinriki Maru, Sekizen Maru, Shigei Maru, and Suwa Maru. Hellcats also attacked a Japanese convoy spotted the previous day and damaged fast transport T.1 southwest of the Marianas. Bunker Hill lost two more pilots and their crew when a TBM-1C Avenger (BuNo 16933) piloted by Lt. (j.g.) Franklin R. Swenson, and a TBF-1C (BuNo 47864) flown by Lt. G.A. Wildhack failed to return from their missions and were declared missing.

The Japanese also shot down Cmdr. William I. Martin, VT-10’s commanding officer, while he flew a mission in a TBM-1C from Enterprise. The pilot parachuted into the sea off Red Beach Three and prior to his rescue observed that the Japanese had marked pre-sited artillery ranges to the reef offshore with red and white pennants. Planners disseminated Martin’s valuable intelligence to the approaching amphibious forces. Enterprise planes supported the marines and soldiers when they stormed Saipan on 15 June.

Japanese planes operating from ashore attacked the ships that evening and at about 1820, F6F-3s of VF-51 from San Jacinto (CVL-30) flying CAP splashed six of seven “dive bombers,” likely Yokosuka D4Y1 Type 2 Judys, approaching the carriers at high altitude. At 1909 seven twin-engined bombers tentatively identified as Yokosuka P1Y Frances’ attacked from ahead. Some of the attackers dropped torpedoes at least one of which passed Enterprise close aboard to port. In addition, other ships in the formation fired antiaircraft guns and 40 millimeter rounds struck Enterprise several times, killing one man and wounding 26 others, and causing superficial damage to her superstructure.

The invasion of Saipan penetrated the inner defensive perimeter of the Japanese Empire and thus triggered A-Go—a Japanese counterattack that led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Their 1st Mobile Fleet, Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō in command, included carriers Taihō, Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Chitose, Chiyōda, Hiyō, Junyō, Ryūhō, and Zuihō. The Japanese intended for their shore-based planes to cripple Mitscher’s air power in order to facilitate Ozawa’s strikes, which were to refuel and rearm on Guam. Japanese fuel shortages and inadequate training bedeviled A-Go, however, and U.S. signal decryption breakthroughs enabled attacks on Japanese submarines that deprived the enemy of intelligence, raids on the Bonin and Volcano Islands disrupted Japanese aerial staging en route to the Marianas, and their main attacks passed through U.S. antiaircraft fire to reach the carriers.

Throughout the day on 19 June 1944, TF 58 repelled Japanese air attacks and slaughtered their planes in what Navy pilots called the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” While the formation steered southeasterly courses at 1036, pickets reported Japanese aircraft approaching bearing 265°, distance 53 miles. Bunker Hill steamed near 14°46'N, 143°2'E, as she sounded general quarters and gunners manned every gun as they fired at enemy dive bombers screaming in for the kill. Gunfire splashed two aircraft that plunged upon her port quarter but they had enough time to release their bombs. A near miss scattered fragments that killed 1st Lt. Gordon A. Stallings, USMC, stationed at a 40-millimeter gun director at frame 45 port side, fatally wounded by a bomb fragment to his abdomen. Pieces of the bomb entered Sea1c G.F. Taphilias’ abdomen, killing the member of a plane handling crew as he fought the battle from his station near the deck edge elevator on the hangar deck. Bomb fragments wounded a further 83 men, who were treated at their battle stations or in sick bay. American fighters circling overhead sent two more enemy planes into the sea nearby, and shortly after noon four more Japanese bombers attacked Bunker Hill. Due to the heavy volume of fire poured out from her gun crews both port and starboard, the Japanese failed to inflict any further damage.

The following afternoon Mitscher launched an air attack at extreme range on the retreating Japanese ships. South Dakota received cursory information indicating the composition of Ozawa’s fleet as four battleships, six carriers, six cruisers, and a dozen destroyers, supported by “a number” of oilers. The ship recorded the estimated range to reach the enemy ships as “approximately 250 miles,” adding ominously that this meant that the planes were to fly at “…the extreme range limit for an air strike.”

Bunker Hill’s airmen launched into the ether and passed a group of six oilers and three destroyers, going on to hit a large carrier protected by a battleship, two cruisers, and several more destroyers. The American bombers flew through a hail of antiaircraft fire to bomb and strafe enemy targets, and received severe damage before flying back to the carrier. The torpedo bombers came next, flying through heavy defensive fire and the billowing smoke from several burning enemy vessels. Helldivers and Avengers from Bunker Hill scored two bomb hits on Hiyō, and an Avenger from Belleau Wood delivered the death blow. American carrier planes sank Hiyō and fleet oilers Gen'yo Maru and Seiyo Maru, and damaged Zuikaku, Chiyōda, Junyō, Haruna, heavy cruiser Maya, destroyers Samidare and Shigure, and fast fleet tanker/seaplane carrier Hayasui.

Bunker Hill’s squadrons faced a difficult day on 20 June 1944, as enemy resistance stiffened. Two pilots from VB-8, Lt. (j.g.) Palmer Touw, flying an SB2C-1C Helldiver (BuNo 00302), as well as Lt. (j.g.) Robert Benshimol and crew (BuNo 00329), all went missing over the Marianas, as did an F6F-3 Hellcat piloted by Ens. E.J. Donner (BuNo 40344), and an F6F-3N (BuNo 65976) flown by Lt. (j.g.) N.L. Davidson from VF(N)-76. Ens. William H. Ransom of VB-8 flew an SB2C-1C (BuNo 18335) during the mission that crashed and Ransom perished in the Helldiver’s demise. Lt. Cmdr. Ronald W. Hoel, an ace with VF-8, was rescued after ditching his Hellcat (BuNo 25760) into the sea. Pilots continued long-range, exhausting searches for any straggling Japanese ships, while on board Bunker Hill, tired gun crews stayed at their battle stations day and night. Seventeen aircraft went down though the majority of the pilots were saved. SB2C-1C Helldivers marked three of the missing planes from Bunker Hill, and their pilots and crews were quickly designated as missing in action.

The carrier aircraft returned on rapidly emptying fuel tanks in the gathering darkness, and the night degenerated into chaos as pilots desperately sought carriers or ditched in the water. Men on board the ships anxiously monitored radar plots and radios, South Dakota recording a VHF transmission “indicating many planes going in water due to being out of gasoline.” Despite the risk of Japanese submarine attacks, Mitscher ordered his ships to show their lights to guide the returning aircraft, thus saving lives when the planes consumed fuel and fell into the sea. Cruisers also fired star shells to illuminate the area, and destroyers rescued many of the men who entered the water.

An SB2C-1C Helldiver of VB-2 from Hornet, which had been waved off with Very signals, attempted to land on Bunker Hill at 2056 but crashed into the barriers before going up on its nose, causing the prop to lodge into the deck and hold the aircraft in that position. The pilot, radioman, and sailors working on the flight deck all escaped without injuries, but a few minutes later at 2108 a TBM-1C (BuNo 25528) of VT-31 from Cabot attempted to land on board Bunker Hill. The Landing Signal Officer waved him off and fired Very signals to indicate a fouled deck but Ens. James Jones Jr., the Avenger pilot, persevered and crashed into the Helldiver as sailors desperately struggled to clear the plane. The collision caused the Avenger to veer to starboard where its wing hit a gun mount, tearing it off. The careening plane then hit the tail of the crashed Helldiver causing the Avenger to flip over onto its back and crash into the ship’s island structure. The Avenger caught fire but the crash and salvage crewmen quickly extinguished the flames. The smashup killed Cmdr. W.C. Smith, Sea1c J.J. Bieber, and Sea1c R.A. Kaster, and inured four other men. Jones suffered first and second-degree burns to his face, arms, and legs. Men jettisoned both aircraft over the side, along with the body of Sea1c Bieber, because they could not remove him from the tangled wreckage. Sailors finally cleared the deck and Bunker Hill resumed flight operations at 2144.

After the carriers recovered the last of the aircraft, the formation turned to westerly courses. Albacore (SS-218) and Cavalla (SS-244) furthermore sank Taihō and Shōkaku in separate attacks during the battle, respectively, and Japanese suicide aircraft narrowly missed Wasp. The Japanese lost 395 carrier planes and an estimated 50 land-based aircraft from Guam. The Americans lost 130 aircraft and 76 pilots and aircrew.

Following the American victory Bunker Hill swung around and anchored at Eniwetok to give her crew a much needed rest (23–27 June). The brief respite proved illusory, however, when she embarked planes of VF-8, VB-8, and VT-8 of CVG-8 and VF-19, VB-19, and VT-19 of CVG-19, and turned seaward for refresher training (27 June–7 July). On the 7th the ship recorded her 10,000th landing. The bloody fighting on Saipan continued but organized resistance ended on 9 July, on the 21st the III Marine Amphibious Corps, Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, USMC, landed on Guam, and three days later the Americans stormed ashore on Tinian. Bunker Hill cleared Eniwetok under Operation Order 10-44 as part of TG 58.3 and next (14–23 July) supported the landings on Guam and Tinian. The ship’s squadrons unleashed some 70 tons of ordnance on the enemy on Tinian on the 18th. The following day called for another bombardment mission, only this time Bunker Hill pulled back while her air group dropped bombs from above and the battlewagons shelled the Japanese with their 16-inch guns. The grueling fighting for the Marianas established the islands as bases from which bombers could reach the Japanese home islands. In addition, the seizure of the islands protected the northern flank of the Allied line of advance from the Central Pacific to the Philippines, toward which the amphibious forces of the Southwest Pacific also thrust.

The task group then (25–28 July 1944) turned southwestward under Operation Order 11-44 and the carriers launched aircraft that attacked Japanese installations and shipping at Fais, Ngulu, Palau, Sorol, Ulithi, and Yap. While the targets seemed meager, an F6F-3 Hellcat pilot of Fighting Eight flying from Bunker Hill scanned the vast expanse of blue sea and sighted guardboat Ryojin Maru off the west coast of Babelthuap, which he promptly blew out of the water with a direct hit by a well-placed bomb. A Hellcat also damaged landing ship T.150, which VF-8’s fighters finished off the next day. F6F-3 Hellcats of VF-51 from San Jacinto splashed an Aichi E13A1 Type 0 reconnaissance floatplane (Jake) and then strafed minelayer Sokuten, touching off her mines, which sank the vessel. Hellcats of VF-51 also damaged destroyer Samidare 30 miles north of Babelthuap, Palau. Samidare later ran aground and Batfish (SS-310) further hurt the ship, and the crew subsequently scuttled her.

Despite liberating the Marianas, Allied planners believed that a base in the western Carolines would support the advance toward the Philippines and selected the Palaus. To divert attention from the projected landings on Peleliu in those islands, ships thrust northwestward toward the Bonin and Volcano Islands. TG 58.1, Rear Adm. Joseph J. Clark, savaged Japanese Convoy 4804 about 25 miles northwest of Muko Jima in the Bonin Islands on 4 August, sinking destroyer Matsu, landing ship T 133, collier Ryuku Maru, transports Enju Maru, No. 7 Unkai Maru, Shogen Maru, and Tonegawa Maru, and cargo ship Hokkai Maru, and damaged Coast Defense Vessel No. 4 and Coast Defense Vessel No. 12. Planes from Cabot damaged fast transport T.4. Meanwhile, planes from TG 58.3, Rear Adm. Alfred E. Montgomery, bombed Japanese airfields on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, and aircraft from Bunker Hill and Lexington sank landing ship T.133 off the coast of Iwo Jima. The following day the Americans returned to the fight and Bunker Hill’s aircraft further damaged T.4 off Chichijima, and for good measure tore into T.2 and left her ablaze, though she too survived the aerial onslaught. The Japanese air resistance proved negligible but their fierce and accurate ground fire shot down and killed Lt. John B. Czerny of VF-8 in his Hellcat (BuNo 41291).

TF 58 became TF 38 on 27 August 1944, and aircraft of TG 38.4 and four escort carriers of Carrier Unit One, Rear Adm. William D. Sample, supported Operation Stalemate II—the landing of the 1st Marine Division on Peleliu. Bunker Hill sailed in TG 38.2.1 and followed Operations Plan 14-44 and Operation Order 2-44 as she hurled planes against the defenders on 7 September. The Japanese on Peleliu prepared their main line of resistance inland from the beaches to escape naval bombardment, and days of preliminary carrier air attacks in combination with intense naval gunfire failed to suppress the tenacious defenders.

The Americans continued on to sweep Japanese air power in the Philippines from their path, and Bunker Hill steamed as part of a battle group for the long awaited return to the those islands. Quick strikes against Davao, Mindanao, met lean resistance on 9 September 1944, and only two days later Bunker Hill’s planes sank two large freighters, heavily damaged five, and slightly damaged five more. Strafing runs accounted for an untold number of destroyed sampans and luggers, not to mention their Japanese crews and soldiers. An escorting destroyer picked up 44 dazed survivors from one of the latter craft.

As the squadrons went out against Alicante, Cebu, Fabric, and Legaspi, Zeros dueled Bunker Hill’s fighters on 13 September 1944. The pilots actively pursued one another in a frenzied scene in the air that continued back on Earth as well. When a downed Bunker Hill pilot (possibly Hellcat driver (BuNo 25261) Lt. (j.g.) E.F. Franze) crash landed at sea, a float plane from a cruiser rescued him against heavy opposition. Hellcats splashed several of the Zeros and went on to strafe ammunition and fuel dumps, hangers, barracks, and other installations.

The marines hit the beaches on Peleliu on 15 September 1944, but the Japanese who survived the preliminary air and naval bombardment exacted a fearsome toll of the leathernecks, so on the 17th Bunker Hill and her consorts returned to the battle and launched aircraft that flew air support missions for the marines and CAP over the ships. In spite of the bloodbath ashore, planners determined to advance the date for the landings in the Philippines, and consequently, Bunker Hull swung around and steamed toward those islands to further weaken the enemy before the landings, with Mitscher breaking his flag in the ship.

Japanese convoy MATA-27, consisting of passenger-cargo ship Hōfuku Maru, army cargo ships Surakaruta Maru and Yuki Maru, cargo vessel Nansei Maru, tanker Ogura Maru No. 1, and merchant tanker Shichiyo Maru, screened by escort ships CD-1, CD-3, CD-5, CD-7, minelayer Enoshima, and auxiliary cable layer Osei Maru, set out from Subic Bay on the morning of 21 September, bound for Takao, Japan. American aircraft sighted the convoy and at 1028 about 40 carrier planes attacked the ships north of the Manisloc Sea and sank all of the merchantman and CD-5. Only later did the Americans learn to their horror that 5,857-ton Hōfuku Maru carried 1,289 British and Dutch POWs, killing more than 1,000 of the helpless men. Their captors packed the captives into the “Hell ship” so tightly that they could not all lie down at once, and did not provide them with facilities so that the men traveled in their own filth and wallowed in misery as she steamed from Singapore to Japan, and stopped in Manila Bay to unload some of the sickest prisoners suffering from disease, thirst, and hunger. The guards stole their Red Cross medical parcels and at least 94 men died while the ship lay to in the bay. Hōfuku Maru resumed her journey but when the planes attacked the crew immediately abandoned ship and made no effort to release the prisoners from their mostly battened-down hatches. The enemy rescued 42 surviving Allied POWs, though the crewmen on one of the destroyers at first knocked them away with bamboo poles before they permitted them to board, and took them to work as slave laborers in the Japanese home islands. Some 242 POWs swam ashore and escaped with the help of Filipino guerilla fighters.

When the Japanese countered the threat and launched air opposition in the Philippines, the Hellcats of VF-8 flew cover while the dive bombers of VB-8 helped wreck Clark and Nichols Fields. This action cost the squadron the lives of Lt. (j.g). Roben D. Horne and his two-man crew of their SB2C-1C Helldiver (BuNo 01013). The next day Bunker Hill’s dive bombers struck and left the enemy seaplane base there in flames. Foul weather plagued air operations until the 24th, when aircraft flew from Bunker Hill’s flight deck to join a strike group that bombed Coron on Masbate, and made a fighter sweep over Negros and Panay. The group flew more than 700 miles to Coron and back, and off Calamian Island in Coron Bay sank Japanese flying boat support ship Akitsushima, cargo ship Kyokusan Maru and army cargo ship Taiei Maru; and damaged ammunition ship Kogyo Maru, army cargo ship Olympia Maru, cargo ships Ekkai Maru and Kasagisan Maru, supply ship Irako, oiler Kamoi and small cargo ship No. 11 Shonan Maru. Off Masbate, the planes sank auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 39 and auxiliary minesweeper Wa 7, merchant cargo ship Shinyo Maru, cargo ships No. 2 Koshu Maru and No. 17 Fukuei Maru, and transport Siberia Maru. Altogether the raiders sank 39 Japanese vessels including destroyer Satsuki. An aviator from Princeton made a forced water landing about five miles west of Milagros, and a Vought OS2U-3 of Observation Squadron (VO) 8 from Massachusetts (BB-59) later rescued the man. Not to be outdone, the Kingfisher attacked a damaged Japanese vessel and a pier as it flew the pilot to safety.

Bunker Hill exacted a heavy toll on the Japanese in the month of September 1944 and on the 28th anchored at Saipan to enjoy a rest, until a typhoon spoiled the short respite. The following day she turned for Ulithi, where she anchored during the first week of the month (1–7 October). On the 6th the night fighting Hellcats of VF(N)-76 detached from the ship, and she then formed TG 38.2.1 and shaped course to the northward under Operation Order 3-44. On 10 October the carriers launched 1,936 sorties against shipping and installations around southern Okinawa. Intelligence reports indicated the likelihood of enemy submarines in a channel between Okinawa and Yagaji-shima, and Enterprise’s second strike included some TBM-1Cs of VT-20 carrying depth charges, but the Avengers failed to locate the submarines. The other Avengers dropped incendiary bombs that started fires in the capital of Naha.

In total the U.S. strikes sank Japanese submarine depot ship Jingei, landing ship T.158, minelayer Takashima, and auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 87 north-northwest of Okinawa. In or near Naha harbor, Navy carrier-based aircraft sank auxiliary minesweepers No. 6 Hakata Maru and Shimpo Maru, guardboats No. 5 Daisei Maru, No. 26 Nansatsu Maru, and Yuki Maru; motor torpedo boats Gyoraitei Nos 493, 496, 498, 500, 805, 806, 810, 812, 813, 814, and Gyoraitei No. 820; army cargo ship Horai Maru; merchant cargo ships Fukura Maru, Koryu Maru, Taikai Maru, and Tetsuzan Maru. Elsewhere in the vicinity, Navy planes sank auxiliary minesweeper No. 1 Takunan Maru off Okino Daito Jima, and army cargo ship Hirota Maru off Miyako Jima, and merchant cargo ship Nanyo Maru off Kume Jima. TF 38 aircraft damaged Coast Defense Ship No. 5 and submarine chaser Ch 58 off Okinawa; and guardboat No. 6 Daisei Maru, cargo ship Toyosaka Maru, and merchant cargo ship No. 7 Takashima Maru outside Koniya harbor. The next day Bunker Hill provided CAP while airplanes from other carriers flew 61 sorties against northern Luzon and damaged escort destroyer Yashiro off San Vicente and cargo vessel No. 6 Banei Maru off Aparri.

Mitscher hurled air strikes against Japanese ships, aerodromes, and industrial plants on Formosa [Taiwan], regarded as the strongest and best-developed base south of the homeland proper, and on northern Luzon (12–13 October 1944). The enemy consequently fought vigorously, and an estimated 30 Zekes and Nakajima Ki-43 (Hayabusas) Oscars intercepted some of the American aircraft over southern Formosa, but Hellcats claimed to splash 18 without loss. Also in this same sweep the planes destroyed grounded enemy bombers, and other minor targets such as a radio station, sampans, and small fuel depots. When the Japanese attempted to seek vengeance later in the afternoon, Bunker Hill’s 5-inch guns and her CAP contributed to defeating the assault.

A 20-millimeter antiaircraft gun hit 25-year-old fighter pilot Lt. (j.g.) Norman W. Imel of VF-8, flying an F6F-5 (BuNo 58835) on a sortie against the enemy on 12 October 1944. Last seen by his fellow pilots bailing out of his Hellcat, rescuers failed to recover him and he was listed as missing in action. Only a year earlier, Imel was known as the “squadron character” that once had “wound up with seven Zekes on his tail on 29 March 1944.” Well-liked and respected, he was known on board Bunker Hill by his nickname, “Red.” After the war investigators learned that he ended up thousands of miles away in the notorious POW camp known as the “Torture Farm” at Ofuna, Japan. Well-known prisoners at Ōfuna included Olympian Lt. Louis S. Zamperini, USAAF, Maj. Gregory Boyington, USMC, and the ill-fated crews of submarines Perch (SS-176), Sculpin (SS-191), and Tang (SS-306), who all languished at the secret base. While not much is known of Imel’s capture after he bailed out, or of his journey to Japan as a POW, he arrived at the camp sometime in early 1945, but on 16 March died of pneumonia. Some of his fellow prisoners speculated that the camp doctor murdered him with a lethal injection of poison. His loss greatly affected crew morale, especially amongst the squadrons.

The Americans splashed more enemy planes and pilots the next day on the 13th, but unfortunately tragedy also struck VB-8 with the loss of three Bunker Hill pilots and two enlisted men during the raids on Formosa: SB2C-3 Helldiver (BuNo 19572) pilot Lt. (j.g.) Peter L. Evanoff, and his squadron mates, fellow Helldiver (BuNo 19504) crews Lt. (j.g.) Prentiss Newman and ARM2c Walter E. Carr, as well as Lt. (j.g.) Harwood S. Sharp, USNR (BuNo 19688), and his radioman ARM1c James R. Langiotti. On 14 October 1944, the fighters and bombers of CVG-8 returned to Formosa and fought through stiff resistance to claim 12 enemy planes in aerial combat and destroy another 20 on the ground. They did not neglect Japanese antiaircraft and other gun emplacements and knocked out several. During the course of the day a further 31 enemy planes were brought down over the task force with one of these claimed by a gun crew on board Bunker Hill.

Four days later carriers launched a strike on the airfields of northern Luzon and shipping lanes in the surrounding areas. Unleashing her busy squadrons once again, Bunker Hill pilots reported 25,000 tons of shipping sunk sinking. Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur, USA, Commander Southwest Pacific Area, intended to develop Leyte as an air and logistics base to support the liberation of the Philippines. On 20 October 1944, Bunker Hill thus steamed into position to support the landings on Leyte, and the following day moved to Cebu Island to bomb airfields and dispersal areas from which the enemy might attempt to harass the American assault forces.

With her support of the landings at Leyte completed, Bunker Hill and her screen came about on the 23rd and steamed in company with TG 30.4 to Seeadler Harbor at Manus for a brief rest (27 October–1 November). An exhausted CVG-8 detached from the ship and she then made for Saipan and anchored there three days later. CVG-4 reported for temporary duty at Saipan, and the following day the ship and her freshly embarked group set out once again for the war and rendezvoused with TG 38.4, Rear Adm. Ralph E. Davison, at 0940 on the 6th, when the carrier and her escorts became TG 38.4.1.

Bunker Hill marked the remainder of the month of November 1944 as a success while her planes hammered Japanese targets throughout the Philippines. Avengers of VT-4 sank a large floating dry dock with four torpedoes, damaged a medium cargo vessel. Antiaircraft fire shot down Ens. Joseph F. Zook of VT-4 and his TBM-1C (BuNo 45698) on 5 November, but he was fortuitously rescued. Around this same time, the ship sent another strike against Cavite Navy Yard that heavily damaged dock installations. The high winds and heavy seas of Typhoon Bill pounded the ship on the 7th and severely hampering planned operations against Japanese targets in and around Manila Bay. Once the typhoon passed, CVG-4 quickly resumed raids against the enemy shipping in Manila Bay and air facilities at Clark Field.

Allied cryptanalysts learned that the Japanese dispatched Convoys TA No. 3 and TA No. 4 to reinforce their troops on Leyte (8–9 November 1944). The enemy’s heavy casualties to date, especially during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, meant that they fought with inadequate numbers of escorts, and the ships sailed one day apart so as to enable their destroyers to escort TA No. 3 and then swing around to screen TA No. 4. Allied land-based planes of the Fifth Air Force sighted the convoys on the 9th and 37 Republic P-47 Thunderbolts escorted 32 North American B-25 Mitchells of the 38th Bomb Group as they flew from Morotai and sank transports Kashii Maru and Kozu Maru, and struck several other vessels.

The Allies decided to finish the job and Halsey hurled 347 planes of TG 38.1, Rear Adm. Montgomery, TG 38.3, Rear Adm. Sherman), and TG 38.4 at TA No. 3 and TA No. 4 as the convoys attempted to reach Ormoc City at Ormoc Bay, Leyte, on the 11th. Bunker Hill changed course with her sister carriers and their consorts to be within range to catapult aircraft. The U.S. planes sank destroyers Hamanami, Naganami, Shimakaze, and Wakatsuki; minesweeper W.30; army cargo ships Mikasa Maru, Saiho Maru, and Tensho Maru; and merchant cargo ship Taizan Maru (ex-St. Quentin). Carrier planes strafed the surviving soldiers as they straggled ashore, to prevent them from joining the fighting on land and oppose the U.S. advance, and in total the attackers killed more than 3,600 of the approximately 4,000 embarked troops.

The three carrier task groups shifted their targets and their aircraft pounded Japanese shipping and port facilities at Manila Bay and in central Luzon on 13 November 1944. Planes sink light cruiser Kiso, destroyers Hatsuharu and Okinami, and auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 116 at Manila, and elsewhere army cargo ships Eiwa Maru, Kakogawa Maru, Kinka Maru, Sekiho Maru, and Teiyu Maru, as well as merchant cargo ships Hatsu Maru, Seiwa Maru, Shinkoku Maru, and Taitoku Maru, and damaged destroyer Ushio. At Cavite, Navy carrier planes sank destroyers Akebono and Akishimo, fleet tanker Ondo, and guardboat Daito Maru. Aircraft also sank army cargo ship Heian Maru at Cabcaben, and auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 116 some 20 nautical miles west of Cavite.

Bunker Hill launched two final strikes the following day on the 14th. Despite a low ceiling and an intense smoke haze, her planes damaged some vessels and strafed enemy aircraft on the ground, destroying at least seven. Ens. Kenneth W. Watkins and Ens. William N. Ostlund, both flying F6F-5 Hellcats of VF-4 (BuNos 58596 and 70387, respectively) were shot down and declared missing in action during the mission. Watkins was “hit by AA fire and crashed in flames,” while Ostlund “was not seen after the dive. It is believed he was hit by AA fire and he did not survive the crash. He is listed as MIA.”

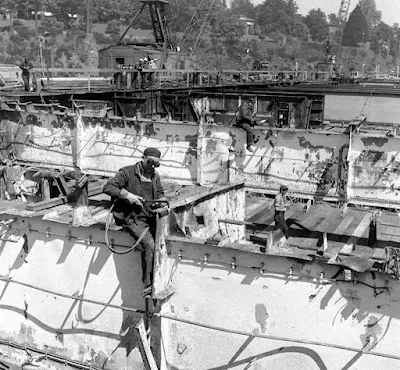

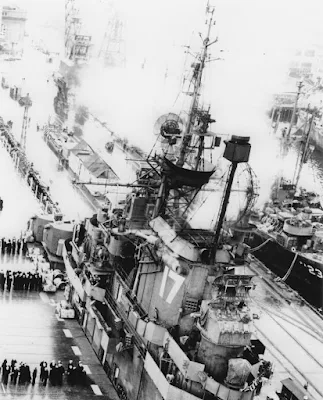

The operation over, TG 30.4 retired on the 16th to Ulithi, where CVG-4 transferred to Essex and CVG-15 boarded to return to the United States. Bedlam infused the atoll on 20 November 1944, when part of the Japanese Kikusai-tai Kaiten Group, comprising submarines I-36 and I-47 (I-37, the group’s third boat, attacked Palau), assailed the anchorage at Ulithi. The two submarines launched four kaiten human torpedoes during the mid-watch, at least one of which, most likely No. 1, Lt. (j.g.) Nishina Sekio, slipped into the lagoon and that morning sank oiler Mississinewa (AO-59). Sekio died in the assault but I-36 and I-47 escaped. Following that shock Bunker Hill stood out of the atoll as TG 30.9.9 for her scheduled voyage home and proceeded to Pearl Harbor (20 November–1 December) and from there to Bremerton, Wash., for a long-overdue yard period. The ship anchored in Sinclair Inlet at Bremerton at 1326 on the 6th, and then dry docked through the rest of the year and into the New Year. After the extensive work CVG-84 boarded with the group’s experienced pilots making up the ship’s fighter, torpedo, and bomber squadrons. Bunker Hill then (21–25 January 1945) steamed for NAS Alameda, Calif., where she embarked the FG-1s of VMF-221.