Cape Torokina is a promontory at the north end of Empress Augusta Bay, along the central part of the western coast of Bougainville, in Papua New Guinea.

This cape formed the southern end of the landing zone where I Marine Amphibious Corps performed an amphibious invasion on November 1, 1943 during Operation Cherry Blossom. The small Puruata Island is located just off the coast to the west of Cape Torokina. The cape and island form a beach to the north which is subject to heavy surf.

The cape was relatively isolated, with a poor trail system to supply the area. A wide swamp stretched inland from the beach area, and the island was heavily forested. During the landing, the cape was the location of a Japanese 75mm gun that inflicted heavy damage upon the landing craft.

Following the landing, an airfield was constructed at the cape. Twenty-five miles of roads were also built around the area.

The Landings at Cape Torokina were the beginning of the Bougainville campaign in World War II, between the military forces of the Empire of Japan and the Allied powers. The amphibious landings by the United States Marine Corps and the United States Army during the month of November 1943 on Bougainville Island in the Solomon Islands of the South Pacific.

The Japanese forces defending Bougainville were part of the General Harukichi Hyakutake 17th Army. This formation reported to the Eighth Area Army under General Hitoshi Imamura at Rabaul, New Britain. The main concentrations of Japanese troops were as follows:

Northern Bougainville: approx. 6,000

Shortland Islands: approx. 5,000

Cape Torokina area: approx. 2,000.

The Bougainville invasion was the ultimate responsibility of Admiral William F. Halsey, commander U.S. Third Fleet, at his headquarters at Nouméa, New Caledonia. The landings were under the personal direction of Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson, commander Third Fleet Amphibious Forces, aboard his flagship attack transport George Clymer. Also aboard was Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, USMC, commander I Marine Amphibious Corps. Vandegrift had already been promoted to Commandant of the Marine Corps, but was asked by Halsey to command the landing force at Bougainville following the accidental death of the original commander, Major General Charles Barrett.

Loaded aboard five attack transports were the men of the 3rd Marine Division (reinforced), Major General Allen H. Turnage commanding. With General Turnage aboard the Hunter Liggett was Commodore Lawrence F. Reifsnider, who had responsibility for the transports as well as three attack cargo ships.

The first wave went ashore along an 8,000-yard front north of and including Cape Torokina at 07:10 hours on 1 November 1943. The 9th Marines assaulted the western beaches while the 3rd Marines took the eastern beaches and the cape itself. The 3rd Marine Raider Battalion captured Puruata Island about 1,000 yards west of the cape.

Because of the possibility of an immediate Japanese counterattack by air units, the initial assault wave landed 7,500 Marines by 07:30 hours. These troops seized the lightly defended area by 11:00 hours, suffering 78 killed in action while virtually annihilating the 270 troops of the Japanese 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment that were defending the area around the beachhead.

Sergeant Robert A. Owens, from Company A, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in eliminating a Japanese 75 mm gun that had been shelling the landing force, after it had destroyed four landing craft and damaged ten others. At the cost of his life, Owens approached the gun emplacement, entered it through the fire port, and drove the crew out the back door.

In the space of eight hours, Admiral Wilkinson’s flotilla unloaded about 14,000 men and 6,200 tons of supplies. He then took his ships out of the area out of fear of an overnight attack by Japanese surface ships. As it turned out, an American force of four light cruisers and eight destroyers encountered a Japanese force of two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and six destroyers in the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay that night (morning of 2 November).

The remainder of the 3rd Marine Division, as well as the US 37th Infantry Division under Major General Robert S. Beightler, and Advance Naval Base Unit No. 7 were landed at Cape Torokina throughout November. As late as Thanksgiving, the beachhead was still under hostile fire. As the sixth echelon of the invasion force was unloading, Japanese artillery fired on the landing ships, inflicting casualties. The Marines silenced these guns the following day.

Torokina Airfield, also known as Cape Torokina Airfield, is a former World War II airfield located at Cape Torokina, Bougainville.

The 3rd Marine Division landed on Bougainville on 1 November 1943 at the start of the Bougainville Campaign, establishing a beachhead around Cape Torokina. Small detachments of the 25th, 53rd, 71st and 75th Naval Construction Battalions landed with the Marines and the 71st Battalion was tasked with establishing a 5,150 feet (1,570 m) by 200 feet (61 m) fighter airfield that would become Torokina Airfield. The airfield became operational on December 10, 1943 when VMF-216 landed with 18 F4U Corsairs.

On 9 March 1944, the Japanese shelled the airfield and forced the squadrons that were based there to take off to avoid damage to their aircraft. Royal New Zealand Air Force squadrons also began operating from the airfield from January 1, 1944. Units assigned to the airfield included:

United States Navy

VC-40 operating Grumman TBF Avengers

ACORN 13

VF(N)-75 operating Vought F4U Corsairs

United States Marine Corps

VMTB-233 operating TBF Avengers

VMF-211 operating F4U Corsairs

VMF-212 operating F4U Corsairs

VMF-215 operating F4U Corsairs

VMF-216 operating F4U Corsairs

VMF(N)-531 operating Lockheed PV-1 Ventura night-fighters

Royal New Zealand Air Force

No. 19 Squadron operating F4U Corsairs

Postwar

Today the airfield is no longer used and most of the runway is overgrown with vegetation.

|

| Map of Bougainville Island showing the US Marine landing zone around Cape Torokina (in Empress Augusta Bay), as well as the location of Japanese bases around the island. |

|

| Map depicting the initial US landings on Bougainville, 1 November 1943. |

|

| A map depicting the Japanese Counterattack on Bougainville during World War II which took place between 9 and 17 March 1944. |

|

| Men of the 3rd Marine Division clamber down a cargo net into an LCM waiting to land them at Torokina on the morning of D-day. |

|

| A Marine dive bomber from VMSB-144 turns gently toward the beachhead area prior to peeling off in one of the prelanding airstrikes at Torokina on D-Day morning. |

|

| The final run in of an LCVP to the beach, while a torpedo-bomber of Marine Air Group 14 makes a last pass at the smoking jungle. |

|

| On the beach at last, 3rd Division Marines fan out on the double to get across the exposed shoreline and plunge, already deployed for combat, into Bougainville jungle. |

|

| Infantrymen of the 3rd Marines come ashore under heavy fire at H-Hour, Cape Torokina, Bougainville on D-Day, 1 November 1943. |

|

| 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines engaged during the landing at Cape Torokina. |

|

| Mopping up Japanese bunkers, two wary Marines of the 3rd Regiment help to make Cape Torokina safe for democracy. |

|

| Surf was extremely rough and many boats broached on the 9th Marines’ beaches. Reading from left to right in background, lie Cape Torokina, Torokina Island, and Puruata Island. |

|

| Mopping up on Torokina Island, a platoon of the 2nd Raider Battalion finds the going tough, despite the fact that only seven Japanese garrisoned the labyrinthine jungles of the tough little island. |

|

| Demolition men of the 3rd Raider Battalion landed on Torokina Island on 3 November, but found that supporting arms had already killed or driven off all Japanese. |

|

| Raiders move up the muddy Piva Trail to safeguard the flank of the beachhead. |

|

| 3rd Defense Battalion anti-aircraft gunners deliver trial fire in order to obtain best ballistic data for the 90mm gun which has just been set up overlooking Cape Torokina. |

|

| Infighting at Koromokina Lagoon took place when Japanese troops of the 54th Infantry came down from Rabaul and attempted a counterlanding against the 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines, on 7 November. |

|

| Sergeant Herbert J. Thomas was awarded the Medal of Honor at Koromokina Lagoon for his heroism in smothering a grenade’s explosion with his own body. |

|

| As were many other American airfields in the Pacific, Torokina Field on Bougainville was literally cut out overnight from the dense jungle which surrounded Empress Augusta Bay. |

|

| Torokina Fighter Field, November 13, 1943. Snaking logs for use in construction of field facilities. |

|

| Torokina Fighter Field, November 15, 1943. 71st Seabees grading taxiway. |

|

| Torokina Fighter Field, December 2, 1943. West end of the field, taken from the control tower. |

|

| First plane to land on the still uncompleted airfield at Cape Torokina. |

|

| RNZAF P-40 taking off from Torokina airfield. |

|

| Marine F4U Corsairs of VMF-216 on Torokina airfield. |

|

| Torokina Fighter Field, December 10, 1943. |

|

| Marine F4U of VMF-216 on Torokina airfield. |

|

| Marine Corsairs of VMF-214 at Cape Torokina. |

|

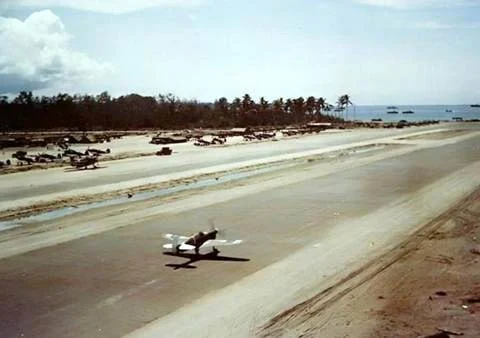

| View of Torokina airfield, Bougainville. Aircraft lining the strip include Vought F4U Corsair fighters, Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers and Lockheed PV Ventura patrol bombers. |

|

| Torokina airfield and Empress Augusta Bay. |

|

| Torokina airfield and Empress Augusta Bay. |