|

| Marines cross the Matanikau River aboard a permanent ferry, complete with landing stages at both ends. The raft was fashioned by Marine engineers from 55-gallon fuel drums. (Official USMC photo) |

The Actions along the Matanikau—sometimes referred to as the Second and Third Battles of the Matanikau—were two separate but related engagements, which took place in the months of September and October 1942, among a series of engagements between the United States and Imperial Japanese naval and ground forces around the Matanikau River on Guadalcanal (island in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia) during the Guadalcanal Campaign. These particular engagements—the first taking place between 23 and 27 September, and the second between 6 and 9 October—were two of the largest and most significant of the Matanikau actions.

The Matanikau River area included a peninsula called Point Cruz, the village of Kokumbona, and a series of ridges and ravines stretching inland from the coast. Japanese forces used the area to regroup from attacks against U.S. forces on the island, to launch further attacks on the U.S. defenses that guarded the Allied airfield (called Henderson Field) located at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal, as a base to defend against Allied attacks directed at Japanese troop and supply encampments between Point Cruz and Cape Esperance on western Guadalcanal, and as a location for watching and reporting on Allied activity around Henderson Field.

In the first action, elements of three U.S. Marine battalions under the command of U.S. Marine Major General Alexander Vandegrift attacked Japanese troop concentrations at several points around the Matanikau River. The Marine attacks were intended to “mop-up” Japanese stragglers retreating towards the Matanikau from the recent Battle of Edson’s Ridge, to disrupt Japanese attempts to use the Matanikau area as a base for attacks on the Marine Lunga defenses, and to destroy any Japanese forces in the area. The Japanese—under the overall command of Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi—repulsed the Marine attacks. During the action, three U.S. Marine companies were surrounded by Japanese forces, took heavy losses, and barely escaped with assistance from a U.S. Navy destroyer and landing craft manned by U.S. Coast Guard personnel.

In the second action two weeks later, a larger force of U.S. Marines successfully crossed the Matanikau River, attacked Japanese forces under the command of newly arrived generals Masao Maruyama and Yumio Nasu, and inflicted heavy casualties on a Japanese infantry regiment. The second action forced the Japanese to retreat from their positions east of the Matanikau and hindered Japanese preparations for their planned major offensive on the U.S. Lunga defenses set for later in October 1942 that resulted in the Battle for Henderson Field.

Background

On 7 August 1942, Allied forces (primarily American) landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of neutralizing the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal Campaign. Taking the Japanese by surprise, by nightfall on 8 August the Allied landing forces had secured Tulagi and nearby small islands, as well as an airfield, later called Henderson Field by Allied forces, under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal.

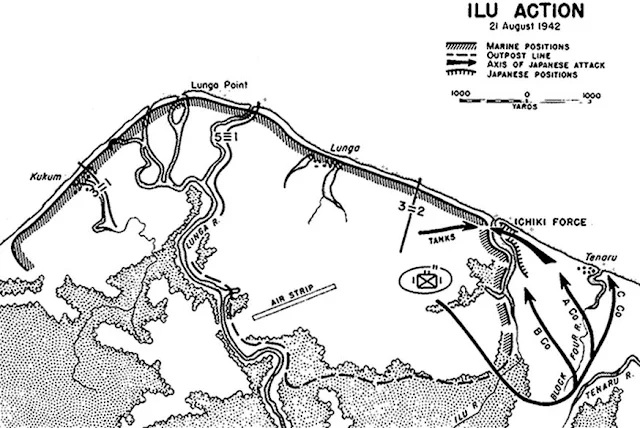

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army’s 17th Army—a corps-sized command based at Rabaul and under the command of Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake—with the task of retaking Guadalcanal from Allied forces. The 17th Army, by this time heavily involved with the Japanese campaign in New Guinea, had only a few units available to send to the southern Solomons area. Of these units, the 35th Infantry Brigade under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi was at Palau, the 4th (Aoba) Infantry Regiment was in the Philippines and the 28th (Ichiki) Infantry Regiment was embarked on transport ships near Guam. The different units began to move towards Guadalcanal immediately, but Ichiki’s regiment—being the closest—arrived first. The “First Element” of Ichiki’s unit—consisting of about 917 soldiers—landed from destroyers at Taivu Point, east of the Lunga perimeter, on 19 August, attacked the U.S. Marine defenses, and were almost completely annihilated during the resulting Battle of the Tenaru on 21 August.

Between 29 August and 7 September, Japanese destroyers (called “Tokyo Express” by Allied forces), plus a convoy of slow barges, delivered the 6,000 men of Kawaguchi’s brigade, including the rest of Ichiki’s regiment (called the Kuma Battalion) and much of the Aoba regiment, to Guadalcanal. General Kawaguchi and 5,000 of the troops landed 20 mi (32 km) east of the Lunga Perimeter at Taivu Point. The other 1,000 troops—under the command of Colonel Akinosuke Oka—landed west of the Lunga Perimeter at Kokumbona. During this time, Vandegrift continued to direct efforts to strengthen and improve the defenses of the Lunga perimeter. Between 21 August and 3 September, he relocated three Marine battalions—including the 1st Raider Battalion, under U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson (Edson’s Raiders)—from Tulagi and Gavutu to Guadalcanal.

Kawaguchi’s Center Body of 3,000 troops began their attacks on a ridge south of Henderson Field beginning on 12 September in what was later called the Battle of Edson’s Ridge. After numerous frontal assaults, Kawaguchi’s attack was repulsed with heavy losses for the Japanese, who retreated back into the jungle on 14 September. Oka’s assault in the west and the Kuma Battalion’s assault in the east were also repulsed by the U.S. Marines over the same two days. Kawaguchi’s units were ordered to withdraw west to the Matanikau Valley to join with Oka’s unit on the west side of the Lunga Perimeter. Most of Kawaguchi’s men reached the Matanikau by 20 September.

As the Japanese regrouped west of the Matanikau, the U.S. forces concentrated on shoring up and strengthening their Lunga defenses. On 18 September, an Allied naval convoy delivered 4,157 men from the 3rd Provisional Marine Brigade (U.S. 7th Marine Regiment) to Guadalcanal. These reinforcements allowed Vandegrift—beginning on 19 September—to establish an unbroken line of defense completely around the Lunga perimeter.

The Japanese immediately began to prepare for their next attempt to recapture Henderson Field. The 3rd Battalion, 4th (Aoba) Infantry Regiment had landed at Kamimbo Bay on the western end of Guadalcanal on 11 September, too late to join Kawaguchi’s attack on the U.S. Marines. By then, though, the battalion had joined Oka’s forces near the Matanikau. Subsequent Tokyo Express runs—beginning on 15 September—brought food and ammunition—as well as 280 men from the 1st Battalion, Aoba Regiment—to Kamimbo on Guadalcanal.

U.S. Marine Lieutenant General Vandegrift and his staff were aware that Kawaguchi’s troops had retreated to the area west of the Matanikau and that numerous groups of Japanese stragglers were scattered throughout the area between the Lunga Perimeter and the Matanikau River. Two previous raids by Marines—on 19 and 29 August—had killed some of the Japanese forces camped in that area but had failed to deny the location as an assembly area and defensive position for the Japanese forces threatening the western portion of the Marine defenses. Vandegrift, therefore, decided to conduct another series of small unit operations around the Matanikau Valley. The purpose of these operations was to “mop-up” the scattered groups of Japanese troops east of the Matanikau and to keep the main body of Japanese soldiers off-balance to prevent them from consolidating their positions so close to the main Marine defenses at Lunga Point. The first operation was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Chesty Puller with a start date of 23 September. The operation would be supported by artillery fire from the U.S. 11th Marine Regiment.

September Action

Prelude

The U.S. Marine plan called for Puller’s battalion to march west from the Lunga perimeter, scale a large terrain feature called Mount Austen, cross the Matanikau River, and then reconnoiter the area between the Matanikau and Kokumbona village. At the same time, the 1st Raider Battalion—now under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith—was to cross at the mouth of the Matanikau to explore the area between the river, Kokumbona, and further west towards Tassafaronga. The Marines thought that there were about 400 Japanese in that area.

The number of Japanese troops in the Matanikau Valley was actually much higher than the Marine estimate. Believing that the Allies might attempt a major amphibious landing near the Matanikau River, Kawaguchi assigned Oka’s 124th Infantry Regiment—numbering about 1,900 men—to defend the Matanikau. Oka deployed his “Maizuru” Battalion around the base of Mount Austen and along the west and east banks of the Matanikau River. The rest of Oka’s force was located west of the Matanikau, but in position to respond quickly to any Allied attacks in that area. Including other Japanese troops located near Kokumbona, total Japanese forces in the general Matanikau area numbered about 4,000.

Action

The 930 men of Puller’s battalion marched west from the Lunga perimeter early on the morning of 23 September. Later that morning, Puller’s troops chased away two Japanese patrols that were reconnoitering the Marine Lunga defenses. Puller’s battalion then camped for the night and prepared to climb Mount Austen the next day.

At 17:00 on 24 September, as Puller’s men hiked up the northeast slope of Mount Austen, they surprised and killed a bivouac of 16 Japanese soldiers. The noise from the skirmish alerted several companies of Oka’s Maizuru Battalion, who were emplaced nearby. The Maizuru troops quickly attacked Puller’s Marines, who took cover and returned fire. Acting on Oka’s orders, the Japanese slowly disengaged while withdrawing towards the Matanikau River, and the engagement was over by nightfall. The Marines counted 30 dead Japanese and had suffered 13 dead and 25 wounded. Puller radioed headquarters and requested help to evacuate the wounded. Vandegrift replied that he would send the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment (2/5) as reinforcements the next day.

2/5—under Lieutenant Colonel David McDougal—rendezvoused with Puller’s unit early on 25 September. Puller sent his casualties back to the Lunga perimeter with three companies of his battalion and continued on with the mission with his remaining company (Company C), his headquarters staff, and 2/5, and they bivouacked for the night between Mount Austen and the Matanikau River.

On the morning of 26 September, Puller and McDougal’s troops reached the Matanikau River and attempted to cross over a bridge previously built by the Japanese that was called the “one-log bridge.” Because of resistance by about 100 Japanese defenders around the bridge, the Marines instead proceeded north along the east bank of the Matanikau to the sand spit on the coast at the mouth of the river. Oka’s troops repulsed a Marine attempt to cross the Matanikau at the sand spit as well as another attempt to cross the one-log bridge later in the afternoon. In the meantime, Griffith’s Raider battalion—along with Merritt A. Edson, commander of the 5th Marine Regiment—joined Puller and McDougal’s troops at the mouth of the Matanikau.

Edson brought with him a “hastily devised” plan of attack—primarily written by Lieutenant Colonel Merrill B. Twining, a member of Vandegrift’s division staff—that called for Griffith’s Raiders—along with Puller’s Company C—to cross the one-log bridge and then outflank the Japanese at the river mouth/sand spit from the south. At the same time, McDougal’s battalion was to attack across the sand spit. If the attacks were successful, the rest of Puller’s battalion would land by boat west of Point Cruz to take the Japanese by surprise from the rear. Aircraft from Henderson Field—as well as Marine 75 mm (2.95 in) and 105 mm (4.1 in) artillery—would provide support for the operation. The Marine offensive would begin the next day, on 27 September.

The Marine attack on the morning of 27 September did not make much headway. Griffith’s Raiders were unable to advance at the one-log bridge over the Matanikau, suffering several casualties, including the death of Major Kenneth D. Bailey and the wounding of Griffith. A flanking attempt by the Raiders further upstream also failed. The Japanese, who had reinforced their units at the mouth of the Matanikau during the night with additional companies from the 124th Infantry Regiment, repulsed the attacks by McDougal’s men.

As a result of “garbled” messages from Griffith because of a Japanese air raid on Henderson Field that disrupted the Marine communication’s net, Vandegrift and Edson believed that the Raiders had succeeded in crossing the Matanikau. Therefore, Puller’s battalion was ordered to proceed with the planned landing west of Point Cruz. Three companies of Puller’s battalion, under Major Otho Rogers, landed from nine landing craft just west of Point Cruz at 13:00. Rogers’ Marines pushed inland and occupied a ridge, called Hill 84, about 600 yd (550 m) from the landing area. Oka—recognizing the seriousness of this landing—ordered his forces to close on Rogers’ Marines from both the west and east.

Soon after occupying the ridge, Rogers’ men came under heavy fire from two directions from Oka’s forces. Major Rogers was hit by a mortar shell that blew him in half, killing him instantly. Captain Charles Kelley—commander of one of the companies—took command and deployed the Marines in a perimeter defense around the ridge to fight back. The Marines on Hill 84 were without radio communication and thus could not call for help. The Marines improvised by using white undershirts to spell out the word “H-E-L-P” on the ridge. A Cactus Air Force (the name for the Allied aircraft operating out of Henderson Field) SBD Dauntless supporting the operation spotted the undershirt message and relayed the message to Edson by radio.

Paul Moore, Jr., a Marine veteran who participated in the battle, described it:

Each... [platoon] was to run across the sandspit until they were opposite the bank, wade across the river, and attack the Japanese battalion, which was dug in with automatic weapons and hand grenades and mortars in the bank.... Well, one platoon went over and got annihilated. Another platoon went over and got annihilated. Then another... we all realized it was insane... But if you’re a Marine, you’re ordered across the goddamn beach and you go.

Edson received a message from the Raider Battalion reporting their failure to cross the Matanikau. Edson, speaking to those around him, stated, “I guess we better call them off. They can’t seem to cross the river.” Puller angrily replied, “You’re not going to throw these men away!” apparently in reference to his men trapped on the west side of the Matanikau, and “stormed” off toward the beach where, with the help of his personal signalman, Puller was able to hail the Navy destroyer USS Monssen that was supporting the operation. Once aboard Monssen, Puller and the destroyer led 10 landing craft towards Point Cruz and established communications with Kelley on the ridge by signal flag.

By this time, Oka’s troops had moved into position to completely cut off the Marines on Hill 84 from the coast. Therefore, Monssen—coordinated by Puller—began to blast a path between the ridge and the beach. After about 30 minutes of firing by the destroyer, the way was clear for the Marines to escape to the beach. Despite taking some casualties from their own artillery fire, most of the Marines made it to the beach near Point Cruz by 16:30. Oka’s troops put heavy fire on the Marines at the beach in effort to keep them from successfully evacuating, and the U.S. Coast Guard crews manning the U.S. landing craft responded with their own heavy fire to cover the Marines’ withdrawal. Under fire, the Marines boarded the landing craft and successfully returned to the Lunga perimeter, ending the action. U.S. Coast Guard Signalman First Class Douglas Albert Munro—Officer-in-Charge of the group of Higgins boats—was killed while providing covering fire from his landing craft for the Marines as they evacuated the beach and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for the action, to date the only Coast Guardsman to receive the decoration.

Aftermath

The results of the action were gratifying to the Japanese, still recovering from their defeat at Edson’s Ridge two weeks prior. Oka’s troops counted 32 bodies of U.S. Marines around Hill 84, and they captured 15 rifles and several machine guns that the Marines left behind. Major General Akisaburo Futami—chief of staff for the 17th Army at Rabaul—noted in his diary that this action was “the first good news to come from Guadalcanal.”

The action—described as “an embarrassing defeat” for the U.S. Marines—resulted in “finger-pointing” among the Marine commanders as they sought to attribute blame. Puller blamed Griffith and Edson, Griffith blamed Edson, and Twining blamed Puller and Edson. Colonel Gerald Thomas—Vandegrift’s operations officer—blamed Twining. The Marines, however, learned from the experience, and the defeat was the only one of that size suffered by U.S. Marine forces during the Guadalcanal campaign.

October Action

Prelude

The Japanese continued to deliver additional forces to Guadalcanal in preparation for their planned major offensive in late October. Between 1 and 5 October, Tokyo Express runs delivered troops from the 2nd Infantry Division, including their commander, Lieutenant General Masao Maruyama. These troops consisted of units from the 4th, 16th, and 29th Infantry Regiments. In an attempt to exploit the advantage gained in the September Matanikau action, Maruyama deployed the three battalions of the 4th Infantry Regiment with additional supporting units under Major General Yumio Nasu along the west side of the Matanikau River south of Point Cruz with three companies from the 4th Infantry Regiment placed on the east side of the river. Oka’s exhausted troops were withdrawn from the immediate Matanikau area. The Japanese units east of the river were to assist in preparing positions from which heavy artillery could fire into the U.S. Marines’ perimeter around Lunga Point.

Aware of the Japanese activity around the Matanikau, the U.S. Marines prepared for another offensive in the area with the objective of driving Japanese forces west and away from the Matanikau valley. Applying lessons learned from the September action, this time the Marines prepared a carefully coordinated plan of action involving five battalions: two from the 5th Marine Regiment, two from the 7th Marine Regiment, and one from the 2nd Marine Regiment augmented with Marine scout and sniper personnel (called the Whaling Group after its commander Colonel William J. Whaling). The 5th Marine’s battalions were to attack across the mouth of the Matanikau while the other three battalions were to cross the Matanikau inland at the “one-log bridge,” turn north, and attempt to trap the Japanese forces between themselves and the coast. This time the Marine division headquarters planned to retain control of the entire operation and carefully arranged detailed support for the operation from artillery and aircraft.

Action

On the morning of 7 October, the two 5th Marine battalions attacked west from the Lunga perimeter towards the Matanikau. With direct-fire support from 75 mm guns mounted on halftracks, plus additional troops supplied by the 1st Raider Battalion, the Marines forced 200 soldiers from the Japanese 3rd Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Infantry into a small pocket on the east side of the Matanikau about 400 yd (370 m) from the river mouth. The Japanese 2nd Company tried to come to the aid of their comrades in the 3rd Company but were unable to cross the Matanikau and took casualties from Marine gunfire. Meanwhile, the two 7th Marine battalions and the Whaling Group reached positions east of the one-log bridge unopposed and bivouacked for the night.

Oblivious of the U.S. Marine offensive, General Nasu sent the 9th Company of the 4th Infantry Regiment’s 3rd Battalion across the Matanikau on the evening of 7 October. The Japanese regimental commander received word of the U.S. Marine operation about 03:00 on 8 October and immediately ordered his 1st and 2nd battalions closer to the river to counter the Marine operation.

Rain on 8 October slowed the U.S. 7th Marines and the Whaling Group as they attempted to cross the Matanikau. Near evening the U.S. 3rd Battalion 2nd Marines reached the first ridge west of the Matanikau about 1 mi (1.6 km) from Point Cruz. Opposite their position on the east bank of the river, Company H from the U.S. 2nd Battalion 7th Marines unknowingly advanced into an exposed position between the Japanese 9th Company on the east bank and the rest of the Japanese 3rd Battalion on the west bank and was forced to withdraw. As a result, the Marines halted their attack for the night and prepared to resume it the next day. Unaware that the Marines threatened their positions on the west bank of the Matanikau, the Japanese commanders—including Maruyama and Nasu—ordered their units to hold in place.

During the night, the survivors of the Japanese 3rd Company, about 150 men, attempted to break out of their pocket and cross the sandbar at the mouth of the Matanikau. The 3rd Company soldiers overran two platoons from the 1st Raiders, who were not expecting an attack from that direction, and the resulting hand-to-hand melee left 12 Marines and 59 Japanese dead. The remaining 3rd Company survivors were able to cross the river and reach friendly lines. According to Frank J. Guidone, a Marine participant in the engagement, “The fight was hours of hell. There was yelling, screams of the wounded and dying; rifle firing and machine guns with tracers piercing the night–(a) combination of fog, smoke, and the natural darkness. Truly an arena of death.”

On the morning of 9 October, the U.S. Marines renewed their offensive west of the Matanikau. The Whaling Group and the 2nd Battalion 7th Marines—commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Herman H. Hanneken—reached the shoreline around Point Cruz and trapped large numbers of Japanese troops between themselves and the Matanikau River, where the Japanese took heavy losses from U.S. artillery and aircraft bombardment. Further west, Puller’s 1st Battalion, 7th Marines trapped the Japanese 2nd Battalion, 4th Infantry in a wooded ravine. After calling for massed artillery fire into the ravine, Puller added the fire of his battalion’s mortars to create, in Puller’s words, a “machine for extermination.” The trapped Japanese troops attempted several times to escape by climbing the opposite side of the ravine, only to be cut down in large numbers by massed Marine rifle and machine gun fire. Having received intelligence information that the Japanese were planning a large surprise offensive somewhere on Guadalcanal, Vandegrift ordered all the Marine units west of the Matanikau to disengage and return to the east side of the river, which was accomplished by the evening of 9 October.

Aftermath and Significance

The Marine offensive inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese 4th Infantry Regiment, killing around 700 Japanese troops. During this operation, 65 Marines were killed.

The same night that the U.S. Marine Matanikau operation ended on 9 October, Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake—the Japanese 17th Army commander—landed on Guadalcanal to personally lead the Japanese forces in their planned large offensive scheduled for later in October. Hyakutake was immediately briefed on the loss of the Japanese positions on the east bank of the Matanikau and the annihilation of one of the 4th Infantry Regiment’s battalions. Hyakutake communicated the news directly to the Army’s General Staff in Tokyo where Lieutenant General Moritake Tanabe of the Operations Division noted in his diary that the loss of the Matanikau position was a “very bad omen” for the planned October offensive.

The Japanese determined that the reestablishment of their forces on the east bank of the Matanikau would be prohibitive in terms of the number of troops required to accomplish it. Therefore, the Japanese devised a plan of attack for their scheduled offensive that sent many of their troops on a long and arduous journey to attack the U.S. Lunga perimeter from inland. The march—which began on 16 October—exhausted the Japanese troops involved to such an extent that it was later considered as one of the major factors in the decisive Japanese defeat in the subsequent Battle for Henderson Field from 23–26 October 1942. Thus, the failure of the Japanese to gain and hold a strong position on the Matanikau proved to have lasting strategic consequences in the battle for Guadalcanal, significantly contributing to the ultimate Allied victory in the campaign.

|

| U.S. Marine patrol crosses the Matanikau River on Guadalcanal, probably in late September or early October 1942. |

|

| U.S. Marine 155mm howitzer fires at Japanese forces on Guadalcanal west of the Matanikau River in late October 1942. |

|

| U.S. Marine forces in action in the Matanikau area, Guadalcanal, August 19, 1942. |

|

| Map of Matanikau action between U.S. Marines and Japanese forces, September 24-27, 1942, on Guadalcanal. |

|

| U.S. Matanikau offensive on Guadalcanal, October 7-9, 1942. |

|

| Map of Allied positions along Matanikau and Lunga Point, Guadalcanal, October 9, 1942. |

|

| Conoley's Action, 24-26 October 1942, near the Matanikau River, Guadalcanal. |