|

| Commander W. S. Sampson, VPB-106, Commanding Officer, 1945, front row, second from right. |

by Frank F. Smith

On 14 July 1944 orders were issued announcing the

reformation of Bombing Squadron 106, Commander William S. Sampson, USN,

commanding. The first official action on the part of the commanding officer of

VB-106 was to take possession and put the officers to work. On the 17th, the

squadron was ousted from its offices at NAS San Diego and directed to set up

shop at Naval Auxiliary Station, Camp Kearney.

During August and September, five Consolidated PB4Y-1’s and

three PB4Y-2 Privateers were acquired for training purposes. The former were

battle-happy boxers but the ground crews worked like beavers and kept them

flying. There was training and schooling in recognition, coding and

communications, navigation, Link trainer, survival and ditching, anti-submarine

warfare, and talks by Consolidated-Vultee representatives on the PB4Y-2, to

mention but a few of the tortures inflicted on all hands. Next came

familiarization flights, where the crews were put through night flying drills,

formation tactics, and overland and overwater navigational flights in search

sectors designated by FAW-14. Then there were several overland navigational and

ferry flights to San Francisco, to Litchfield Park (the PB4Y-2 modification

center in Arizona), and to NAS Hutchinson, Kansas, and NAS Jacksonville,

Florida.

By October the squadron had been officially re-designated

Patrol Bombing Squadron 106. Fourteen out of fifteen PB4Y-2’s permanently

assigned to the squadron had been received. And the complement of officers and

enlisted men was virtually complete, with sixty officers and 164 enlisted men.

Flight training went into high gear with simulated and live bombing exercises,

against both land and sea targets, and flare illumination and attack with

miniature bombs on ships and submarines. In addition, there was extensive

training in camera gunnery exercises with fighter aircraft for opposition,

glide and horizontal bombing attacks and radar coastal patrols.

Simulated trans-Pacific flights were successfully completed

in November, and the important task of “shaking down” the crews and making them

into a well-knit, smooth-working team was accomplished. In certain cases, men

who were not adapted to their jobs due to physical or other incapacities were

replaced by better qualified men. Overall, the crews were welded into a

smooth-running unit by the coaching of patrol plane commanders, chiefs and the

more experienced enlisted men.

The advance echelon, consisting of Lieutenant Commander

Chuck Thompson, Lieutenants Grant Younger and “Smitty” Smith, Ensigns Bob

Brown, Bob Hartle, Hank Schnieder, and Bill Barry, and seventy-two enlisted

men, departed by ship for Hawaii during the month. The stage was set for the

trans-Pacific flight to Hawaii, at that time the longest overwater air route in

the world, and the curtain was up. For some this was an old story, especially

for the old hands of VPB-106, but for most it was a new experience, one entered

into with mixed emotions—of not unnatural trepidation and eagerness for the

adventure. Takeoffs were made at night. Each night was the same. Close to

thirty-five tons of airplane, stowed gear and humanity were taxied out to the

end of the runway. Hatches battened down. The engines were run up, one by one,

and the mags given a final check. Brakes were released, props overcame the

inertia of the stationary object, the wheels began to roll and the strip lights

went by. Lights from the operations tower lighted up the interior of the plane

for a fleeting instant as it passed by. More strip lights. Faster, faster. The

nose wheel was off the deck now. Speed, more speed. Only two more strip lights

to go, then one. Throttles were all the way forward, the engines pulling 51-28,

all they would take, as the aircraft became airborne. Soon the lights of San

Diego faded back into the distance, and there was only the night ahead and

dependence on four Pratt & Whitney engines, the skill of those at the controls,

the stars for navigation. and a faith that none would fail.

Lieutenants Frank Liek and Ed Leonard led off the first of

these trans-Pacific flights on 5 December. Unusual weather so delayed further

departures that the last flights did not leave Kearney until the 21st.

Lieutenant Commander Benny Caldwell and Lieutenant Joe Huder were forced to

turn back at the equi-time point because of excessive fuel consumption. But

they went the full distance on their second try. Unpredicted headwinds made it

impossible for seven of the squadron’s fifteen aircraft to proceed directly to

NAS Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii.

Six landed at Hilo and one at Molokai for refueling.

Shortest time for the flight was fourteen hours thirteen minutes, while the

longest flight was eighteen hours twenty minutes to Molokai. Ten more minutes

and those tanks would have been bone dry.

Until 10 February 1945, the squadron was based at NAS

Kaneohe. It was at Kaneohe that a run of bad luck had begun for Lieutenant Burt

Knust who was photo officer for the squadron. While on a final approach to

Kaneohe, a Grumman Duck collided with his aircraft. The collision was heard

rather than felt by the crew. The Duck struck the number one prop of the PB4Y-2

and then went underneath it. No injuries were sustained by Lieutenant Knust’s

crew, and he brought the aircraft in for a successful landing. Five days later,

Lieutenant Knust and his full crew took off from Kaneohe on a routine patrol

flight, flying a temporarily assigned PB4Y-1. While on the return leg and while

approximately 200 miles from Oahu, Lieutenant Knust started to let down from

8,000 feet to avoid unfavorable weather conditions at that altitude. Transfer

of fuel from the auxiliary wing tanks was in progress. At about 2,000 feet the

pilot noticed flames around the cowl flaps of number two engine. Although the

flow of fuel to number two was stopped, the flames spread over the wing.

Shortly thereafter number one engine cut out. Neither prop could be feathered.

Bombs were jettisoned, but time did not permit closure of the bomb bay doors.

The aircraft took an uncontrollable turn to port, the port wing striking the

water, resulting in the aircraft cartwheeling. It broke up on impact, with the

center wing section and one bomb bay tank being the only parts to remain

afloat. All but one of the crew members survived the crash, and were picked up

some thirty hours later by a Navy patrol craft.

By February, Kaneohe and FAW-2 had bid goodbye to VPB-106,

which had now been transferred to Tinian. The flight from Kaneohe was made in

easy stages, flying by day with night stopovers. First stop point was Johnston

Island, that dot of treeless sand in the middle of nowhere, which is nothing

more than a wayside gas station for skytravelers flying between the Hawaiian

and Marshall Islands. The second night was spent at battle-scarred,

boomerang-shaped Kwajalein. From there it was an eight-hour flight to West

Field, Tinian.

The first patrols were flown on the 18th, these being

barrier patrols in the path of Admiral Richmond Turner’s TF 51, en route to Iwo

Jima to launch amphibious assault operations against that island.

During the succeeding twelve days, interdictory patrols were

flown daily, covering the withdrawal and refueling operations of TF 58,

subsequent to its second strike against Tokyo on the 25th. Meanwhile, screening

flights continued covering TF 51, assaulting Iwo Jima. From the 26th through

the 28th, aircraft of the squadron were called upon to assist in screening

operations while units of TF 58 were rendezvousing and refueling preparatory to

striking Okinawa. In addition to providing cover for these two task forces,

squadron aircraft acted as a flying communication center for relaying messages

between various task groups of the fleet and also assisted units, including the

fueling units, in joining up with one another.

The old adage that bad luck runs in threes caught up with

Lieutenant Burt Knust when, on 16 February, in attempting a landing at West

Field, Tinian, the starboard landing gear of his Privateer buckled and gave

way. He managed to keep the plane from ground looping and no one was even so

much as scratched. However, the plane was damaged beyond repair, and after

rather extensive salvage and stripping operations, it was finally laid to rest

amongst other forgotten and broken-down hulks.

Lieutenants Jim Schultz with crew 14 and Ed Ashley with crew

15 drew enemy blood first when, during a photo and recon mission over Truk

Lagoon on 20 February, they teamed up to strafe a lugger which was plying

across the northern fleet anchorage, and also military barracks on Param

Island. Barracks and ship were left smoking. Less than a week later, Lieutenant

Ashley and the same crew went out gunning for Japanese picket boats, found two

near the Borodino Guntos and left one seriously damaged, the other moderately

damaged.

March, the first full month of combat operations, was a hard

one with 114 combat missions flown. The availability of Iwo Jima as a staging

area had the effect of lengthening the radius of Empire-bound search sectors

from Tinian. Generally, these sector searches ran from 2,000 to 2,400 miles,

lasting sixteen hours, with refueling at Iwo Jima on the return leg.

It was 5 March when the strip on Iwo Jima was sufficiently

improved for operational use. At that time, only two invasion beaches, Mt.

Suribachi, and the landing strip area (less than one-third of the island) had

been won from the Japanese.

Lieutenant Commanders Mears and Caldwell, and Lieutenant

Knust, together with pilots from VPB-116, made the first landings and takeoffs

for PB4Y aircraft on combat missions from Iwo after its invasion by U.S.

Marines. Japanese snipers continued to operate near the airstrip for some time

thereafter, and Lieutenant Schultz’s Privateer was shot at during one takeoff.

In those early days, when Iwo was far from being secured, the No. 1 airstrip,

or south field, was scarcely long enough to accommodate fighters, let alone

four-engine bombers, and was being lengthened by Seabees working under combat

conditions. It had many soft spots where bomb craters had been hurriedly

filled. The control tower consisted of a portable radio mounted on a jeep. As

if this didn’t make it difficult enough to get in and out of the strip, the approach

had to be made too close to Mt. Suribachi for comfort, especially when weather

restricted visibility which was usually the case. Our troops were shelling the

northern part of the island from Mt. Suribachi and since the arc of their fire

went directly over the airstrip, fire had to be withheld before planes could

land safely. Finally, the end of the strip had not been cleared of enemy mines

and the take-off path subjected planes to Japanese anti-aircraft and rifle

fire.

Lieutenant Joe Swiencicki’s crew strafed, bombed and set

fire to a couple of pickets near the Honshu coast despite accurate

anti-aircraft fire. Lieutenant Frank Leik’s boys took on a sub chaser and also

encountered a Mavis flying boat near Borodino Gunto but were dissuaded from

closing the attack by a Nick fighter and the proximity of the enemy-held

strips. Lieutenant Commander Jerry Barlow and crew took three anti-aircraft

hits in a seventy-minute battle with two highly maneuverable picket boats while

he made four runs and started a good-sized fire on one. Lieutenant Commander

Mears chased a big Emily flying boat which escaped by ducking into a cloud, and

Lieutenant Commanders Goodloe and Loewer teamed up against two heavily-armed

steel pickets close to the Japanese mainland. Goodloe’s bombardier made a drop

straddling the smaller of the two ships. A mass of flames, smoke, a split ship,

a slick and debris, all within a few seconds, bore witness to a job well done.

While on a photo mission over Truk Lagoon, Lieutenant Ben Joy’s crew caught a

lugger towing two barges and blew them out of the water.

It fell to Lieutenant Joe Huber and Lieutenant John

Ripplinger and their crews to inflict the greatest damage on the enemy during

the month of March. They teamed up with Iwo-based rocket-packing Venturas of

VPB-151 to sink two tough picket boats, earning them a well-done from the

commander, Navy Search and Bombardment Group, Tinian, who, himself, was patrol

plane commander of one of the Venturas. Lieutenant Huber’s plane sustained

serious damage to its elevator control and tail surfaces and a large hole in the

fuselage by the radar station, from medium anti-aircraft. At the end of the

month, Lieutenant “Hob” Hoblin was forced to feather a prop 900 miles from base

and had no alternative but to make for Clark Field in the Philippines, some

fifty miles distant. After fighting his way through a tropical storm of almost

typhoon intensity, he landed safely with three engines at Clark Field.

During the first weeks of April, a combination of excellent

radar technique, good hunting weather, alert tactics, and accurate bombing

added a 200-foot picket boat of 1,500-tons to the list of kills. At the

beginning of the second week in April, part of the squadron was based at

Central Field, Iwo Jima, under a rotational relief plan whereby approximately

six to eight aircraft and crews were stationed at Iwo while the balance stood

by at Tinian. This change in operations cut a long haul to the Empire in half

and at the same time doubled the bomb load potential as well as permitting

closer and longer inspections of the Empire coastline and coastal shipping. Except

on rare occasions, Japan’s coastal shipping was conspicuous by its absence.

However, the picket boat trade continued to flourish, though these boats stayed

closer to the mainland after the capture of Iwo Jima. They still were

well-armed, highly maneuverable, and even more dangerous targets, since with

stepping up of the B-29 raids on Japan the need for weather information and

early detection of such raids, which only the picket boats could provide, had

magnified the importance of their work.

Toward the end of April, word arrived that the squadron was

to move to Palawan, Philippines. Half the squadron was then at Iwo Jima and the

remainder at Tinian. Within two hours after the orders had been received at

Iwo, planes were taking off for Tinian. By 8 May, all of the squadron was based

at Palawan except for Lieutenant Jim Coughlan, whose plane was having landing

gear trouble.

By the end of May, almost 11,000 tons of enemy shipping had

been destroyed or seriously damaged, and three Japanese planes shot down and

three more damaged. Sector searches extended 2,000-plus miles, although a few

went out only 1,700 miles. Areas covered included the west coast of the

Celebes, the east coast of Borneo past Pare Pare, Balikpapan and the Makassar

satellite airfields, through Makassar Straits into the Java Sea, and the west

coast of Borneo past Brunei Bay, Kuching and Pontianak, and south into the Java

Sea.

May was crowded with action, culminating in the last days of

the month with the first close recon of Singapore to be made by a Navy

aircraft. Earlier in the war China-based B-29s had made an attack on that naval

bastion, but no further Allied recon was made. On 23 May, Lieutenant Commander

Goodloe’s crew extended a sector search to make the first photo recon of

Singapore, flying from the Philippines. After reaching the outer straits

Goodloe proceeded to make a clockwise circle of Singapore Island. He followed

Johore Straits past the former great British naval base, where two Japanese

heavy cruisers were located, and across the giant causeway connecting Singapore

with Malaya to the north. He then headed toward Singapore town and dock area

and the nearby airdromes. Several new fields were located and numerous photos

taken. Not a shot was fired at the Privateer which was flying between 8,000 and

9,000 feet. While on a retirement course over the huge Changi Point airdrome,

bombs were dropped on twin-engine planes in the revetment area, destroying one

or more of them.

Within a week, five more Privateers visited Singapore to

obtain pictures. However, this time the Japanese provided reception committees,

averaging from three to six Oscar, Tojo and Zeke fighters. A Jake made one

appearance and a hasty exit. In an engagement between Lieutenant Commander

Goodloe’s Privateer and an Oscar, the latter was smoked and went into a nose

dive, disappearing in a cloud bank. Later, both his Privateer and a Zeke took

some hits. While these dogfights were in progress, several Oscars with altitude

advantage were dropping bomb clusters on the Privateer but without success.

Once again, Goodloe obtained many excellent photos, despite the fighter

opposition and heavy anti-aircraft fire from both cruisers and the naval air

base area.

June was the worst month for the squadron. It started badly

on the first day and it never took a turn for the better. First of all, it was

Lieutenant Commander Pappy Mears and his crew, and two weeks later Lieutenant

Commander Goodloe and his crew. Six officers and seventeen enlisted men were

missing in action. Whatever damage the squadron inflicted upon the enemy during

the month, or during all its months of operations, could not balance out the

loss of these gallant pilots and aircrewmen.

Lieutenant Commander Mears led a two-plane section, composed

of his crew and Lieutenant Heyler’s of VPB-111, to make a close inspection of

shipping, the Japanese cruisers, airfields, and other military installations at

Singapore. Fired at by heavy anti-aircraft and attacked by nearly a dozen

Oscars, he continued on with the assigned mission, gunners from both Navy

planes holding off the Japanese fighters while the necessary photos were being

taken. One Oscar got a hit in the number three engine of Mears’ Privateer,

causing the engine to burst into flames and the plane to lose altitude. The

combined fire of the two planes kept the enemy fighters from closing. The fire

in the engine went out, only to reappear again. Then it was all over the

aircraft, and it was forced to ditch.

On 14 June, Lieutenant Commander Goodloe and crew flew a

long sector patrol to the Malay coast and up into the Gulf of Siam in search of

a Japanese convoy believed to have been in that general area. Lieutenant

Younger, who had the adjoining sector but was too far away to be of any

assistance, intercepted a message from Goodloe, saying he had one engine shot

out and was proceeding to Rangoon. Younger relayed this message back to base,

and Rangoon was promptly alerted. However, Rangoon reported no arrival and an

exhaustive search, which continued through the end of the month, was likewise

unavailing.

July was to be the last full month of combat operations for

the squadron. Lieutenants Liek and Jones and their crews started the month off

by destroying a string of motor barges and “Sugar Dogs.” Lieutenant

Swiencicki’s crew took over and bombed some warehouses at Kuching, Borneo, and

Lieutenant Vernon Smith’s crew destroyed three “Sugar Dogs” and strafed a

blockhouse, also at Kuching. About that time the airstrip was closed down for

two weeks repair, so a detachment of the squadron was sent to Mindoro to fly

patrols from that base. The remainder stayed at Palawan and took it easy, which

was not difficult to do.

The range factor was such that, operating from Mindoro, all

sectors were whitecappers except for one which took in both the west side of

Borneo and the island of the Natoena and Anambas groups, short of Singapore.

Accordingly, the shipyards at Kuching and Pontianak in Borneo were reduced to a

state of permanent inactivity by Lieutenants Schultz, Huber, Jones and McKoin.

Radar stations on the Anambas and Bintan Islands were worked over by

Lieutenants Jones and Younger. The Malay shipyards at Trengganu were plastered

by the crews of Lieutenants Meirhoffer and Ripplinger.

The hazardous Singapore recon flights ware continued,

sometimes in the company of 13th Air Force Lightnings. Nearly every crew flew

one or more of these patrols.

On 24 July, one year and two days after he had assumed

command, Commander Sampson, who had been ordered to FAW-17 to become executive

officer, handed over his squadron to the capable hands of Lieutenant Commander

Harry Hickman in a brief ceremony. He then shook hands with all present and

wished them God speed. For the original members of the squadron the end was at

hand. It was as simple as the beginning. In between, everyone had done his job

well. No commanding officer could have desired more than just that.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Warren

S. Hickox, former VPB-106 pilot, and Kenn Rust. Photographs and illustrations

provided by Frank F. Smith.

|

| VPB-106 “The Wolverators” insignia. |

|

| VPB-106 Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer. |

|

| VPB-106 Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer. |

|

| Crew of PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X397, VPB-106. |

|

| Crew of PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X385, VPB-106. |

|

| Crew of PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X393, VPB-106 |

|

| VPB-106 PB4Y-2 Privateer undergoing maintenance at Palawan Island, 1945. |

|

| VPB-106 PB4Y-2 Privateer, BuNo 59390, number X390, “Umbriaga,” parked off strip at Palawan, 1945. |

|

| Close-up of the nose artwork on “Umbriaga,” with “Sleepy Time Gal” nickname. The nose art has been revised. |

|

| PB4Y-2, “Umbriaga,” with “Sleepy Time Gal” nickname, with the revised nose art. |

|

| Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X390, “Umbriaga.” |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, BuNo 59390, number X390, original “Umbriaga” artwork; nicknamed “Sleepy Time Gal.” |

|

| Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, number 395, nose showing mission markings. |

|

| Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, number 395, nose showing mission markings. |

|

| Japanese “Sugar Dog” patrol boats being built in North Borneo, photographed by a VPB-106 plane, 1944. |

|

| Brunei Bay, Borneo, photographed from a VPB-106 aircraft in 1945. A Japanese submarine can be seen at left center. |

|

| Japanese “Sugar Dog” seen under attack by a VPB-106 aircraft on 12 January 1945. Many of these Japanese patrol boats were caught in open seas and strafed this way. |

|

| VPB-106 bomb dump on Palawan Island, circa 1945. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, ‘Tiger Pussy,’ number X384. |

|

| Close-up of nose artwork on same PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X384. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X384, of VPB-106, believed to be the same plane as in the photos on the previous page, but showing the artwork on the left side of the nose. |

|

| VPB-106 Privateer (BuAer 59818), number X818, seen at Palawan Island, 1945. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “Indian Made.” Was later coded number X505. |

|

| Close up of nose art PB4Y-2 Privateer, “Indian Made.” |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, number 448, “Modest O’Miss II.” |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “Lady of Leisure,” code unknown (almost completely covered by nose artwork). Note five victory kill flags. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “Blue Diamond,” number X396. Pilot’s name beneath cockpit is “Diamond Jim Schultz”; other names visible are “Delphey” and “Hoppy.” |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “Blue Diamond,” number X396. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “The Super-chief,” code unknown. Note “Lex Loci” at left. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “The Super-chief,” code unknown. Note “Lex Loci” at left. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer (BuAer 59370) of VPB-106, “Joy Rider,” number X370, flown by Lt. B. F. Joy, USNR. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer (BuAer 59370) of VPB-106, “Joy Rider,” number X370, flown by Lt. B. F. Joy, USNR. The nose art has been revised. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106, “Tarfu,” number 433X. Pilot’s name is “Flying Pole”; “Little Ann” above figure. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, VPB-106. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106. |

|

| Members of VPB-106. |

|

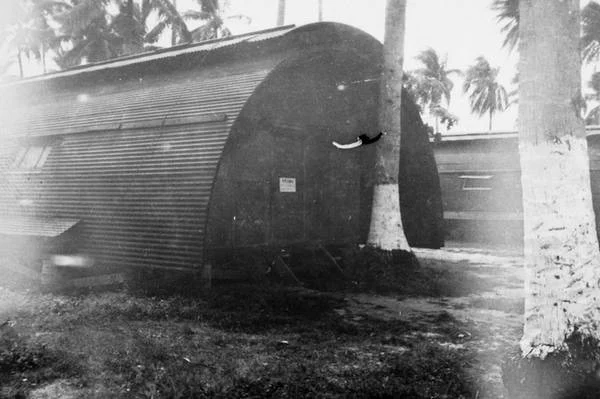

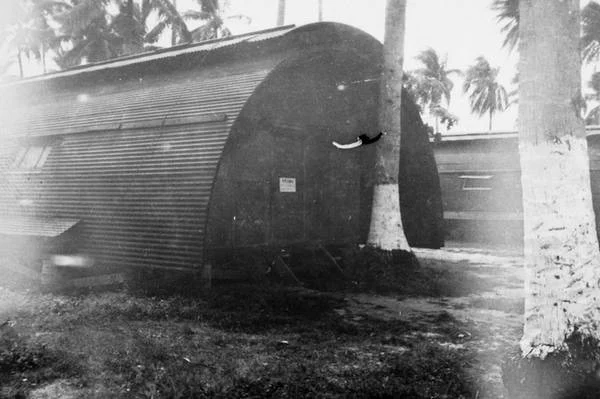

| VPB-106 crew quarters. |

|

| Quarters for crews of VPB-106. |

|

| Quarters for crews of VPB-106. |

|

| Airstrip and control tower with flying boats in background. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, VPB-106. |

|

| Crew of PB4Y-2 Privateer, VPB-106. |

|

| Crew quarters, VPB-106. |

|

| Manfred Herbert Mueller, Aviation Radioman Third Class, DFC, VPB-106. |

|

| Manfred Herbert Mueller, Aviation Radioman Third Class, DFC, VPB-106. |

|

| Air Medal Award Citation for Manfred Herbert Mueller. |

|

| Third Air Medal Award Citation for Manfred Herbert Mueller. |

|

| Distinguished Flying Cross Award Citation for Manfred Herbert Mueller. |

|

| Honorable Discharge of Manfred Herbert Mueller, Aviation Radioman Third Class, DFC, VPB-106. |

|

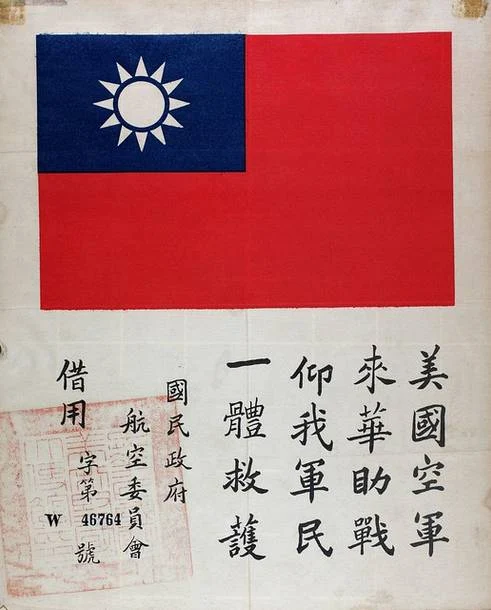

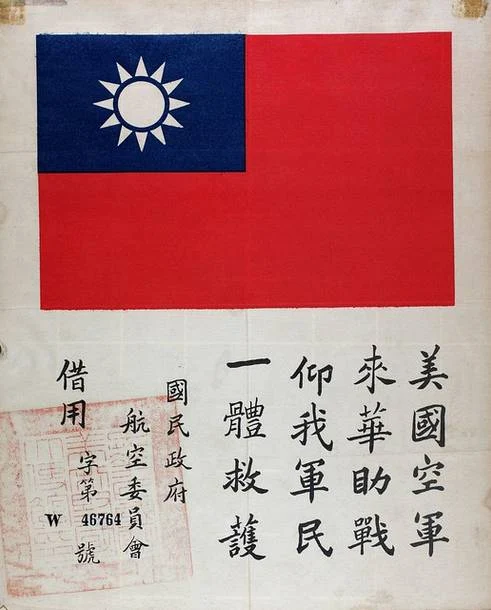

| Paper Blood Chit carried by crewmen of PB4Y-2 Privateers, VPB-106. |

|

| Notice of Air Medal Award and Temporary Citation for Daniel Edward Rego, Jr. |

|

| Air Medal Award Citation for Daniel Edward Rego, Jr. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, VPB-106. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, number Y491, “Tail Chaser,” VPB-106. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateers, VPB-106. |

|

| VPB-106 crew quarters, Iwo Jima. Mt. Suribachi in background. |

|

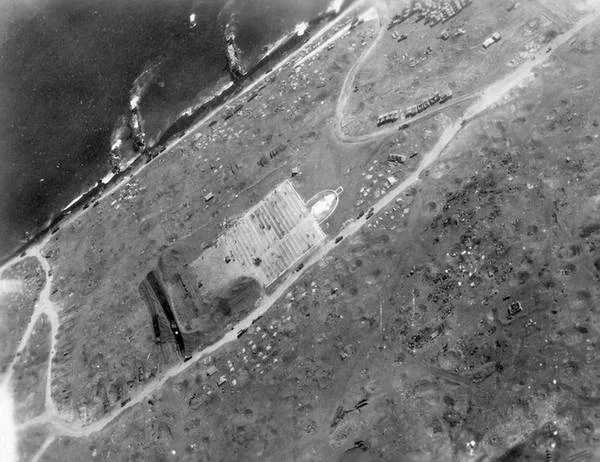

| Airfield, Iwo Jima. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateers of VPB-106. |

|

| Members of VPB-106. |

|

| Crew quarters, Iwo Jima. Note Grumman TBF Avenger in background. |

|

| Grumman J2F Duck, VPB-106. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, “Lucky-Leven,” VPB-106. |

|

| VPB-106 unit members. and PB4Y-2 Privateers in background. |

|

| VPB-106 crewmen pose on the tail of their PB4Y-2 Privateer. |

|

| Member of VPB-106 armed to the teeth. |

|

| Quonset hut quarters. |

|

| Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer BuNo 59412, number X412. |

|

| Crew of PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X412, VPB-106. Note “Barbara’s Daddy” under nose window. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, VPB-106. |

|

| Unnamed PB4Y-2 Privateer, number X390, VPB-106. |

|

| PB4Y-2 Privateer, “Off We Go,” VPB-106. The nose art and lettering has been digitally enhanced by an unknown party. |

|

| Member of VPB-106 in flight gear and survival equipment. |

|

| Strafing run by PB4Y-2, number X395, Crew III, VPB-106, Belawai, 6 June 1945. |

|

| Airfield rendered useless by bombing attacks of VPB-106. |

|

| Members of VPB-106 pose with a captured Japanese gun in front of the sign to the U.S. Naval Base, Tinian. |

|

| Members of VPB-106 pose in front of a Japanese anti-aircraft gun. |

|

| Remains of an installation on Iwo Jima, photographed by a member of VPB-106. |

|

| Remains of a Japanese battery on Iwo Jima, photographed by a member of VPB-106. |

|

| Remains of an installation on Iwo Jima, photographed by a member of VPB-106. |

|

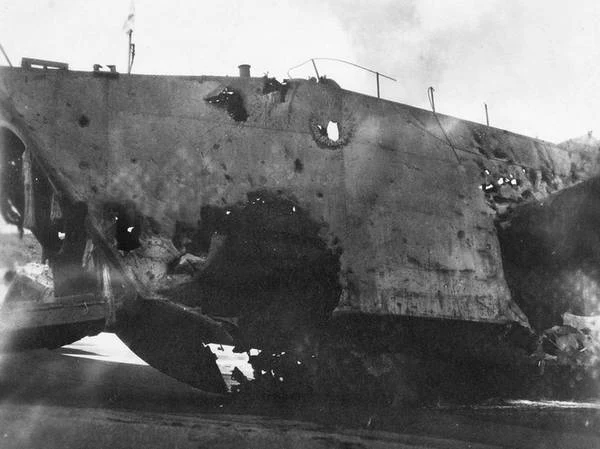

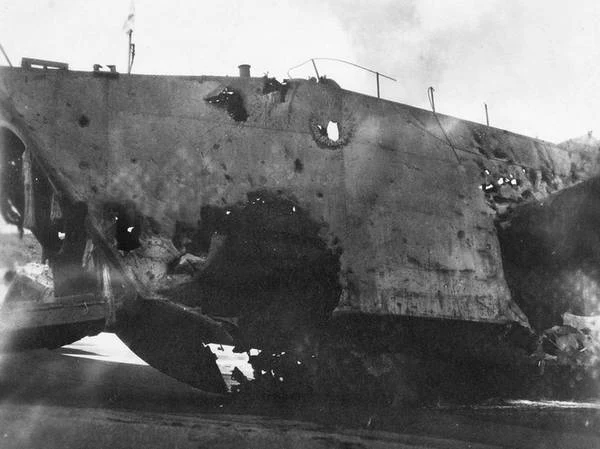

| Wreckage of Japanese No. 1 class landing ship beached and destroyed by American aircraft using it for target practice. The No.1-class landing ship (Dai 1 Gō-gata Yusōkan) was a class of amphibious assault ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, serving during and after World War II. The IJN also called them 1st class transporter (1-Tō Yusōkan). |

|

| Wreckage of Japanese No. 1 class landing ship. |

|

| Wreckage of Japanese No. 1 class landing ship. |

|

| VPB-106 unit members examine damage to Japanese No. 1 class landing ship. Was this ship a target for the aircraft of VPB-106 prior to the invasion of Iwo Jima? And was it used as target practice after the invasion? |

|

| 3rd Marine Division cemetery on Iwo Jima photographed by a member of VPB-106. |

|

| 3rd Marine Division cemetery on Iwo Jima. Mt. Suribachi in background. Photographed by a member of VPB-106. |

|

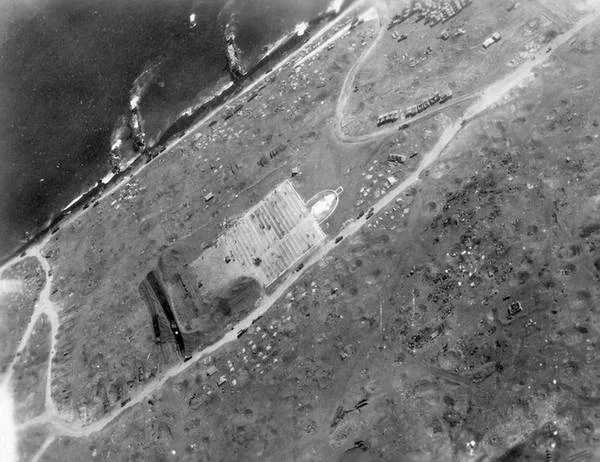

| Aerial view of 3rd Marine Division cemetery on Iwo Jima taken from a VPB-106 aircraft. |

|

| VPB-106 unit members examine knocked out Japanese HA-GO light tank on Iwo Jima. |

|

| VPB-106 members at the entrance to a Japanese bunker on Iwo Jima. |

|

| Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, number 767, VPB-106. |

|

| View from waist window of port wing of Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer of VPB-106 as landing gear is retracted after takeoff. |

|

| Paper Blood Chit carried by VPB-106 crews. |

|

| Surrender leaflet dropped on Japanese installations by aircraft of VPB-106. |

Excellent and accurate account of the VPB-106 squadron. My Great Uncle was the tail gunner aboard the Mears PB4Y-2 #59563, when it was shot down near Singapore with a loss of all 12 aboard.

ReplyDelete