The Battle of Tassafaronga, sometimes referred to as the Fourth Battle of Savo Island or, in Japanese sources, as the Battle of Lunga Point, was a nighttime naval battle that took place on November 30, 1942, between United States (US) Navy and Imperial Japanese Navy warships during the Guadalcanal campaign. The battle took place in Ironbottom Sound near the Tassafaronga area on Guadalcanal.

In the battle, a US warship force of five cruisers and four destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright attempted to surprise and destroy a Japanese warship force of eight destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka. Tanaka’s warships were attempting to deliver food to Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

Using radar, the US warships gained surprise, opened fire, and sank one of the Japanese destroyers. Tanaka and the rest of his ships reacted quickly and launched numerous Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes at the US warships. The Japanese torpedoes hit and sank one US cruiser and heavily damaged three others, enabling the rest of Tanaka’s force to escape with no significant additional damage but also without completing the intended supply mission. Although a severe tactical defeat for the US, the battle had little strategic impact; the Japanese were unable to take advantage of the victory to further resupply or otherwise assist in their ultimately unsuccessful efforts to recapture Guadalcanal from Allied forces.

Background

On August 7, 1942, U.S. and some Allied forces landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings were meant to deny the Japanese access to bases that they could use to threaten supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and to secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of neutralizing the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings began the six-month Guadalcanal campaign.

The 2,000 to 3,000 Japanese personnel on the islands were taken by surprise, and by nightfall on August 8 the 11,000 Allied troops, under the command of Lieutenant General Alexander Vandegrift, secured Tulagi and nearby small islands as well as the Japanese airfield under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. The Allies later renamed the airfield Henderson Field. Allied aircraft operating out of Henderson were called the “Cactus Air Force” (CAF) after the Allied code name for Guadalcanal. To protect the airfield, the U.S. Marines established a perimeter defense around Lunga Point. Reinforcements over the next two months increased the number of U.S. troops at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal to more than 20,000.

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army’s 17th Army, a corps-sized command based at Rabaul and under the command of Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, the task of retaking the island. Units of the 17th Army began to arrive on Guadalcanal on August 19 to drive Allied forces from the island.

Because of the threat by CAF aircraft based at Henderson Field, the Japanese were rarely able to use large, slow transport ships to deliver troops and supplies to the island. Instead, the Japanese used warships based at Rabaul and the Shortland Islands to carry their forces to Guadalcanal. The Japanese warships, mainly light cruisers and destroyers from the Eighth Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, were usually able to make the round trip down “The Slot” to Guadalcanal and back in a single night, thereby minimizing their exposure to CAF air attack. Delivering the troops in this manner, however, prevented most of the soldiers’ heavy equipment and supplies, such as heavy artillery, vehicles, and much food and ammunition, from being carried to Guadalcanal with them. These high-speed warship runs to Guadalcanal occurred throughout the campaign and were later called the “Tokyo Express” by Allied forces and “Rat Transportation” by the Japanese.

The Japanese attempted several times between August and November 1942 to recapture Henderson Field and drive Allied forces from Guadalcanal, to no avail. The last attempt by the Japanese to deliver significant additional forces to the island failed during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal of November 12–15.

On November 26, Japanese Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura took command of the new Eighth Area Army at Rabaul. The new command encompassed both Hyakutake’s 17th Army in the Solomons and the 18th Army in New Guinea. One of Imamura’s first priorities upon assuming command was the continuation of the attempts to retake Henderson Field and Guadalcanal. The Allied offensive at Buna in New Guinea, however, changed Imamura’s priorities. Because the Allied attempt to take Buna was considered a more severe threat to Rabaul, Imamura postponed further major reinforcement efforts to Guadalcanal to concentrate on the situation in New Guinea.

Supply Crisis

Due to a combination of the threat from CAF aircraft, US Navy PT boats stationed at Tulagi, and a cycle of bright moonlight, the Japanese had switched to using submarines to deliver provisions to their forces on Guadalcanal. Beginning on November 16, 1942, and continuing for the next three weeks, 16 submarines made nocturnal deliveries of foodstuffs to the island, with one submarine making the trip each night. Each submarine could deliver 20 to 30 tons of supplies, about one day’s worth of food, for the 17th Army, but the difficult task of transporting the supplies by hand through the jungle to the frontline units limited their value to sustain the Japanese troops on Guadalcanal. At the same time, the Japanese tried to establish a chain of three bases in the central Solomons to allow small boats to use them as staging sites for making supply deliveries to Guadalcanal, but damaging Allied airstrikes on the bases forced the abandonment of this plan.

On November 26, the 17th Army notified Imamura that it faced a critical food crisis. Some front-line units had not been resupplied for six days and even the rear-area troops were on one-third rations. The situation forced the Japanese to return to using destroyers to deliver the necessary supplies.

Eighth Fleet personnel devised a plan to help reduce the exposure of destroyers delivering supplies to Guadalcanal. Large oil or gas drums were cleaned and filled with medical supplies and food, with enough air space to provide buoyancy, and strung together with rope. When the destroyers arrived at Guadalcanal they would make a sharp turn, the drums would be cut loose, and a swimmer or boat from the shore could pick up the buoyed end of the rope and return it to the beach, where the soldiers could haul in the supplies.

The Eighth Fleet’s Guadalcanal Reinforcement Unit, based in the Shortland Islands and under the command of Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka, was tasked by Mikawa with making the first of five scheduled runs using the drum method on the night of November 30. Tanaka’s unit was centered on the eight ships of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 2, with six destroyers assigned to carry from 200 to 240 drums of supplies apiece, to Tassafaronga at Guadalcanal. Tanaka’s flagship Naganami along with Takanami acted as escorts. The six drum-carrying destroyers were Kuroshio, Oyashio, Kagerō, Suzukaze, Kawakaze, and Makinami. To save weight, the drum-carrying destroyers left their reloads of Type 93 torpedoes (Long Lances) at the Shortlands, leaving each ship with eight torpedoes, one for each tube.

After the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, US Vice Admiral William Halsey, commander of Allied forces in the South Pacific, had reorganized US naval forces under his command, including, on November 24, the formation of Task Force 67 (TF67) at Espiritu Santo, comprising the heavy cruisers USS Minneapolis, New Orleans, Pensacola, and Northampton, the light cruiser Honolulu, and four destroyers (Fletcher, Drayton, Maury, and Perkins). US Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright replaced Thomas Kinkaid as commander of TF67 on November 28.

Upon taking command, Wright briefed his ship commanders on his plan for engaging the Japanese in future, expected night battles around Guadalcanal. The plan, which he had drafted with Kinkaid, stated that radar-equipped destroyers were to scout in front of the cruisers and deliver a surprise torpedo attack upon sighting Japanese warships, then vacate the area to give the cruisers a clear field of fire. The cruisers were then to engage with gunfire from 10,000 yards (9,100 m) to 12,000 yards (11,000 m). The cruisers’ floatplanes would scout and drop flares during the battle.

On November 29, Allied intelligence personnel intercepted and decoded a Japanese message transmitted to the 17th Army on Guadalcanal alerting them to Tanaka’s supply run. Informed of the message, Halsey ordered Wright to take TF67 to intercept Tanaka off Guadalcanal. TF67, with Wright flying his flag on Minneapolis, departed Espiritu Santo at 27 knots (31 mph; 50 km/h) just before midnight on November 29 for the 580 miles (930 km) run to Guadalcanal. En route, destroyers Lamson and Lardner, returning from a convoy escort assignment to Guadalcanal, were ordered to join up with TF67. Lacking the time to brief the commanding officers of the joining destroyers of his battle plan, Wright assigned them a position behind the cruisers. At 17:00 on November 30, Wright’s cruisers launched one floatplane each for Tulagi to drop flares during the expected battle that night. At 20:00, Wright sent his crews to battle stations.

Tanaka’s force departed the Shortlands just after midnight on November 30 for the run to Guadalcanal. Tanaka attempted to evade Allied aerial reconnaissance aircraft by first heading northeast through Bougainville Strait before turning southeast and then south to pass through Indispensable Strait. Paul Mason, an Australian coastwatcher stationed in southern Bougainville, reported by radio the departure of Tanaka’s ships from Shortland and this message was passed to Wright. At the same time, a Japanese search aircraft spotted an Allied convoy near Guadalcanal and communicated the sighting to Tanaka who told his destroyer commanders to expect action that night and that, “In such an event, utmost efforts will be made to destroy the enemy without regard for the unloading of supplies.”

Battle

Prelude

At 21:40 on November 30, Tanaka’s ships sighted Savo Island from Indispensable Strait. The Japanese ships were in line ahead formation, interval 600 meters (660 yd), in the order of Takanami, Oyashio, Kuroshio, Kagerō, Makinami, Naganami, Kawakaze, and Suzukaze. At this same time, TF67 entered Lengo Channel en route to Ironbottom Sound. Wright’s ships were in column in the order Fletcher, Perkins, Maury, Drayton, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Pensacola, Honolulu, Northampton, Lamson, and Lardner. The four van destroyers led the cruisers by 4,000 yards (3,700 m) and the cruisers steamed 1,000 yards (910 m) apart.

At 22:40, Tanaka’s ships passed south of Savo about 3 miles (5 km) offshore from Guadalcanal and slowed to 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h) as they approached the unloading area. Takanami took station about 1 mile (2 km) seaward to screen the column. At the same time, TF67 exited Lengo Channel into the sound and headed at 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h) towards Savo Island. Wright’s van destroyers moved to a position slightly inshore of the cruisers. The night sky was moonless with between 2 miles (3 km) and 7 miles (11 km) of visibility. Because of extremely calm seas which created a suction effect on their pontoons, Wright’s cruiser floatplanes were delayed in lifting off from Tulagi harbor, and would not be a factor in the battle.

At 23:06, Wright’s force began to detect Tanaka’s ships on radar near Cape Esperance on Guadalcanal about 23,000 yards (21,000 m) away. Wright’s destroyers rejoined the column as it continued to head towards Savo. At the same time, Tanaka’s ships, which were not equipped with radar, split into two groups and prepared to shove the drums overboard. Naganami, Kawakaze, and Suzukaze headed for their drop-off point near Doma Reef while Makinami, Kagerō, Oyashio, and Kurashio aimed for nearby Tassafaronga. At 23:12, Takanami’s crew visually sighted Wright’s column, quickly confirmed by lookouts on Tanaka’s other ships. At 23:16, Tanaka ordered unloading preparations halted and “All ships attack.”

Action

At 23:14, operators on Fletcher established firm radar contact with Takanami and the lead group of four drum-carrying destroyers. At 23:15, with the range 7,000 yards (6,400 m), Commander William M. Cole, commander of Wright’s destroyer group and captain of Fletcher, radioed Wright for permission to fire torpedoes. Wright waited two minutes and then responded with, “Range on bogies [Tanaka’s ships on radar] excessive at present.” Cole responded that the range was fine. Another two minutes passed before Wright responded with permission to fire. In the meantime, the US destroyers’ targets escaped from an optimum firing setup ahead to a marginal position passing abeam, giving the American torpedoes a long overtaking run near the limit of their range. At 23:20, Fletcher, Perkins, and Drayton fired a total of 20 Mark 15 torpedoes towards Tanaka’s ships. Maury, lacking SG radar and thus having no contacts, withheld fire.

At the same time, Wright ordered his force to open fire. At 23:21, Minneapolis complied with her first salvo, quickly followed by the other American cruisers. Cole’s four destroyers fired star shells to illuminate the targets as previously directed then increased speed to clear the area for the cruisers to operate.

Because of her closer proximity to Wright’s column, Takanami was the target of most of the Americans’ initial gunfire. Takanami returned fire and launched her full load of eight torpedoes, but was quickly hit by American gunfire and, within four minutes, was set afire and incapacitated. As Takanami was destroyed, the rest of Tanaka’s ships, almost unnoticed by the Americans, were increasing speed, maneuvering, and preparing to respond to the American attack. All of the American torpedoes missed. Historian Russell S. Crenshaw, Jr. postulates that had the twenty-four Mark 15 torpedoes fired by U.S. Navy destroyers during the battle not been fatally flawed, the outcome of the battle might have been different.

Tanaka’s flagship, Naganami, reversed course to starboard, opened fire and began laying a smoke screen. The next two ships astern, Kawakaze and Suzukaze, reversed course to port. At 23:23, Suzukaze fired eight torpedoes in the direction of the gun flashes from Wright’s cruisers, followed by Naganami and Kawakaze which fired their full loads of eight torpedoes at 23:32 and 23:33 respectively.

Meanwhile, the four destroyers at the head of the Japanese column maintained their heading down the Guadalcanal coast, allowing Wright’s cruisers to pass on the opposite course. Once clear of Takanami at 23:28, Kuroshio fired four and Oyashio fired eight torpedoes in the direction of Wright’s column and then reversed course and increased speed. Wright’s cruisers maintained the same course and speed as the 44 Japanese torpedoes headed in their direction.

At 23:27, as Minneapolis fired her ninth salvo and Wright prepared to order a course change for his column, two torpedoes, from either Suzukaze or Takanami, slammed into her forward half. One warhead exploded the aviation fuel storage tanks forward of turret one and the other knocked out three of the ship’s four firerooms. The bow forward of turret one folded down at a 70-degree angle and the ship lost power and steering control. Thirty-seven men were killed.

Less than a minute later a torpedo hit New Orleans abreast of turret one and exploded the ship’s forward ammunition magazines and aviation gasoline storage. The blast severed the ship’s entire bow forward of turret two. The bow twisted to port, damaging the ship’s hull as it was wrenched free by the ship’s momentum, and sank immediately off the aft port quarter. Everyone in turrets one and two perished. New Orleans was forced into a reverse course to starboard and lost steering and communications. A total of 183 men were killed. Herbert Brown, a seaman in the ship’s plotting room, described the scene after the torpedo hit,

I had to see. I walked alongside the silent turret two and was stopped by a lifeline stretched from the outboard port lifeline to the side of the turret. Thank God it was there, for one more step and I would have pitched head first into the dark water thirty feet below. The bow was gone. One hundred and twenty five feet of ship and number one main battery turret with three 8 inch guns were gone. Eighteen hundred tons of ship were gone. Oh my God, all those guys I went through boot camp with - all gone.

Pensacola followed next astern in the cruiser column. Observing Minneapolis and New Orleans taking hits and slowing, Pensacola steered to pass them on the port side and then, once past, returned to the same base course. At 23:39, Pensacola took a torpedo abreast the mainmast. The explosion spread flaming oil throughout the interior and across the main deck of the ship, killing 125 of the ship’s crew. The hit ripped away the port outer driveshaft and the ship took a 13-degree list and lost power, communications, and steering.

Astern of Pensacola, Honolulu’s captain chose to pass Minneapolis and New Orleans on the starboard side. At the same time, the ship increased speed to 30 knots (35 mph; 56 km/h), maneuvered radically, and successfully transited the battle area without taking any damage while maintaining main battery fire at the rapidly disappearing Japanese destroyers.

The last cruiser in the American column, Northampton, followed Honolulu to pass the damaged cruisers ahead to starboard. Unlike Honolulu, Northampton did not increase speed or attempt any radical maneuvers. At 23:48, after returning to the base course, Northampton was hit by two of Kawakaze’s torpedoes. One hit 10 feet (3 m) below the waterline abreast the after engine room, and four seconds later, the second hit 40 feet (12 m) further aft. The after engine room flooded, three of four shafts ceased turning, and the ship listed 10 degrees to port and caught fire. Fifty men were killed.

The last ships in Wright’s column, Lamson and Lardner, failed to locate any targets and exited the battle area to the east after being mistakenly fired on by machine guns from New Orleans. Cole’s four destroyers circled completely around Savo Island at maximum speed and reentered the battle area, but the engagement had already ended.

Meanwhile, at 23:44 Tanaka ordered his ships to break contact and retire from the battle area. As they proceeded up Guadalcanal’s coast, Kuroshio and Kagerō fired eight more torpedoes towards the American ships, which all missed. When Takanami failed to respond to radio calls, Tanaka directed Oyashio and Kuroshio to go to her assistance. The two destroyers located the burning ship at 01:00 on December 1 but abandoned rescue efforts after detecting American warships in the area. Oyashio and Kuroshio quickly departed the sound to rejoin the rest of Tanaka’s ships for the return journey to the Shortlands, which they reached 10 hours later. Takanami was the only Japanese warship hit by American gunfire and seriously damaged during the battle.

Aftermath

Takanami’s surviving crew abandoned ship at 01:30, but a large explosion killed many more of them in the water, including the destroyer division commander, Toshio Shimizu, and the ship’s captain, Masami Ogura. Of her crew of 244, 48 survived to reach shore on Guadalcanal and 19 of them were captured by the Americans.

Northampton’s crew was unable to contain the ship’s fires and list and began to abandon ship at 01:30. The ship sank at 03:04 about 4 miles (6 km) from Doma Cove on Guadalcanal. Fletcher and Drayton rescued the ship’s 773 survivors.

Minneapolis, New Orleans, and Pensacola were able to make it the 19 miles (31 km) to Tulagi on the morning of December 1 where they were berthed for emergency repairs. The fires on Pensacola burned for 12 hours before being extinguished. Pensacola departed Tulagi for rear area ports and further repair on December 6. After construction of temporary bows from coconut logs, Minneapolis and New Orleans departed Tulagi for Espiritu Santo or Sydney, Australia on December 12. All three cruisers required lengthy and extensive repairs. New Orleans returned to action in August, Minneapolis in September, and Pensacola in October 1943.

The battle was one of the worst defeats suffered by the US Navy in World War II, third only to the Attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Savo Island. The battle, along with the losses suffered during the Battle of Savo Island, Cape Esperance and the Naval Battles of Guadalcanal temporarily left the US Navy with only 4 operational heavy cruisers and 9 light cruisers in the entire Pacific Ocean. In spite of his defeat in the battle, Wright was awarded the Navy Cross, one of the highest American military decorations for bravery, for his actions during the engagement. Mitigating to some degree the destruction of his task force, Wright, in his after-action report, claimed that his force sank four Japanese destroyers and damaged two others. Halsey, in his comments on Wright’s report, placed much of the blame for the defeat on Cole, saying that the destroyer squadron commander fired his torpedoes from too great a distance to be effective and should have “helped” the cruisers instead of circling around Savo Island. The recriminations did not affect Coles’s career, who had won a Navy Cross of his own for actions during the Naval battles of Guadalcanal; he continued to lead destroyer squadrons in the Pacific and was later promoted to Rear Admiral.

Tanaka claimed to have sunk a battleship and two cruisers in the battle.

The results of the battle led to further discussion in the US Pacific Fleet about changes in tactical doctrine and the need for technical improvements, such as flashless powder. It was not until eight months later that the naval high command recognized there were serious problems with the functioning of the torpedoes. The Americans were still unaware of the range and power of Japanese torpedoes and the effectiveness of Japanese night battle tactics. In fact, Wright claimed that his ships must have been fired on by submarines since the observed position of Tanaka’s ships “make it improbable that torpedoes with speed-distance characteristics similar to our own” could have caused such damage, though Tanaka states that his torpedoes were fired at a range as short as three miles. The Americans would not recognize the true capabilities of their Pacific adversary’s torpedoes (particularly the surface-ship-fired Type 93 “Long Lance”) and night tactics until well into 1943. After the war, Tanaka said of his victory at Tassafaronga, “I have heard that US naval experts praised my command in that action. I am not deserving of such honors. It was the superb proficiency and devotion of the men who served me that produced the tactical victory for us.”

In spite of their defeat in the battle, the Americans had prevented Tanaka from landing the desperately needed food supplies on Guadalcanal, albeit at high cost. A second Japanese supply delivery attempt by 10 destroyers led by Tanaka on December 3 successfully dumped 1,500 drums of provisions off Tassafaronga, but strafing American aircraft sank all but 310 of them the next day before they could be pulled ashore. On December 7, a third attempt by 12 destroyers was turned back by US PT boats off Cape Esperance. The next night, two US PT boats torpedoed and sank the Japanese submarine I-3 as it attempted to deliver supplies to Guadalcanal. Based on the difficulties experienced trying to deliver food to the island, the Japanese Navy informed Imamura on December 8 that they intended to stop all destroyer transportation runs to Guadalcanal immediately. After Imamura protested, the navy agreed to one more run to the island.

The last attempt to deliver food to Guadalcanal by destroyers in 1942 was led by Tanaka on the night of December 11 and consisted of 11 destroyers. Five US PT boats met Tanaka off Guadalcanal and torpedoed his flagship Teruzuki, severely damaging the destroyer and injuring Tanaka. After Tanaka transferred to Naganami, Teruzuki was scuttled. Only 220 of the 1,200 drums released that night were recovered by Japanese army personnel on shore. Tanaka was subsequently relieved of command and transferred to Japan on December 29, 1942.

On December 12, the Japanese Navy proposed that Guadalcanal be abandoned. Despite opposition from Japanese Army leaders, who still hoped that Guadalcanal could eventually be retaken from the Allies, on December 31, 1942 Japan’s Imperial General Headquarters, with approval from the Emperor, agreed to the evacuation of all Japanese forces from the island and the establishment of a new line of defense for the Solomons on New Georgia. The Japanese evacuated their remaining forces from Guadalcanal over three nights between February 2 and February 7, 1943, conceding the hard fought campaign to the Allies. Building on their success at Guadalcanal and elsewhere, the Allies continued their campaign against Japan, ultimately culminating in Japan’s defeat and the end of World War II.

|

| U.S. Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright. |

|

| United States Navy Task Force 67 just before the Battle of Tassafaronga on November 30, 1942. USS Fletcher is in the foreground, followed by other destroyers and, in the distance, cruisers. |

|

| The U.S. Navy heavy cruiser USS Minneapolis (CA-36) underway at sea on 25 June 1938. She is wearing an “E” award, for engineering excellence, on her after smokestack. |

|

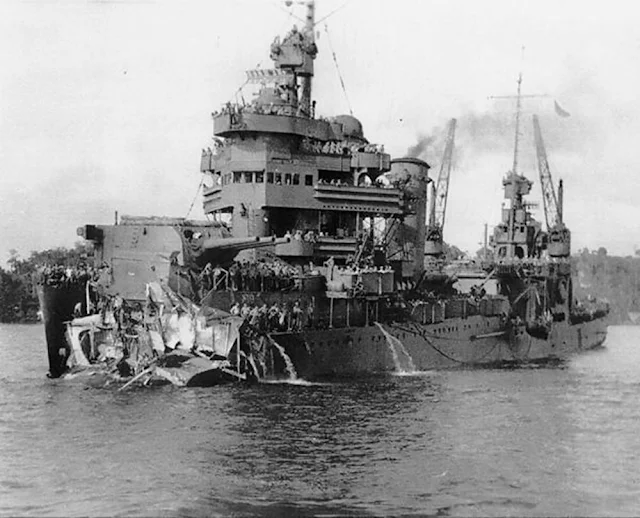

| USS New Orleans near Tulagi on 1 December 1942. The bow was blown off forward of turret two during the Battle of Tassafaronga the night before, killing 180+ of the ship’s crew. |

|

| US Navy chart of the Battle of Tassafaronga based on accounts by both Japanese and US participants. |