|

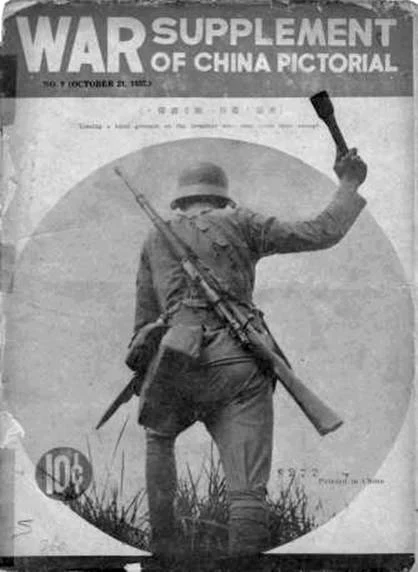

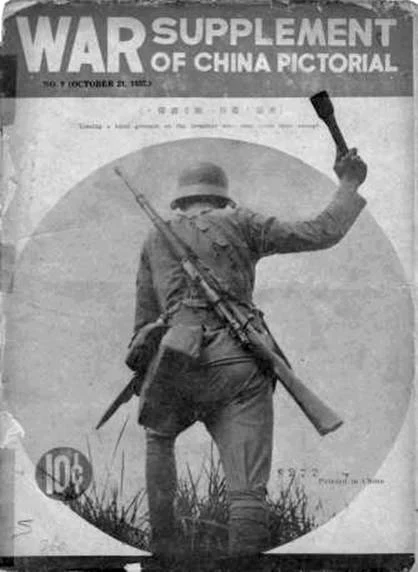

| National Revolutionary Army soldiers march to the front in 1939. |

The

Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China and the

Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to

Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part of World War II, and

often regarded as the beginning of World War II in Asia. It was the largest

Asian war in the 20th century and has been described as "the Asian

Holocaust", in reference to the scale of Japanese war crimes against Chinese

civilians. It is known in China as the War of Resistance against Japanese

Aggression.

On

18 September 1931, the Japanese staged the Mukden incident, a false flag event

fabricated to justify their invasion of Manchuria and establishment of the

puppet state of Manchukuo. This is sometimes marked as the beginning of the

war. From 1931 to 1937, China and Japan engaged in skirmishes, including in

Shanghai and in Northern China. Chinese Nationalist and Communist forces,

respectively led by Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, had fought each other in

the Chinese Civil War since 1927. In late 1933, Chiang Kai-shek encircled the

Chinese Communists in an attempt to finally destroy them, forcing the

Communists into the Long March, resulting in the Communists losing around 90%

of their men. As a Japanese invasion became imminent, Chiang still refused to

form a united front before he was placed under house arrest by his subordinates

who forced him to form the Second United Front in late 1936 in order to resist

the Japanese invasion together.

The

full-scale war began on 7 July 1937 with the Marco Polo Bridge incident near

Beijing, which prompted a full-scale Japanese invasion of the rest of China.

The Japanese captured the capital of Nanjing in 1937 and perpetrated the

Nanjing Massacre. After failing to stop the Japanese capture of Wuhan in 1938,

then China's de facto capital at the time, the Nationalist government relocated

to Chongqing in the Chinese interior. After the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression

Pact, Soviet aid bolstered the National Revolutionary Army and Air Force. By

1939, after Chinese victories at Changsha and with Japan's lines of

communications stretched deep into the interior, the war reached a stalemate.

The Japanese were unable to defeat Chinese Communist Party forces in Shaanxi,

who waged a campaign of sabotage and guerrilla warfare. In November 1939,

Chinese nationalist forces launched a large scale winter offensive, and in

August 1940, communist forces launched the Hundred Regiments Offensive in

central China.

In

December 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and declared

war on the United States. The US increased its aid to China under the

Lend-Lease Act, becoming its main financial and military supporter. With Burma

cut off, the United States Army Air Forces airlifted material over the

Himalayas. In 1944, Japan launched Operation Ichi-Go, the invasion of Henan and

Changsha. In 1945, the Chinese Expeditionary Force resumed its advance in Burma

and completed the Ledo Road linking India to China. China launched large

counteroffensives in South China and repulsed a failed Japanese invasion of

West Hunan and recaptured Japanese occupied regions of Guangxi.

Japan

formally surrendered on 2 September 1945, following the atomic bombings of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Soviet declaration of war and subsequent invasions of

Manchukuo and Korea. The war resulted in the deaths of around 20 million

people, mostly Chinese civilians. China was recognized as one of the Four

Policemen, regained all territories lost, and became one of the five permanent

members of the United Nations Security Council. The Chinese Civil War resumed

in 1946, ending with a communist victory and the Proclamation of the People's

Republic of China in 1949.

Names

In

China, the war is most commonly known as the "War of Resistance against

Japanese Aggression", and shortened to "Resistance against Japanese

Aggression" or the "War of Resistance". It was also called the

"Eight Years' War of Resistance", but in 2017 the Chinese Ministry of

Education issued a directive stating that textbooks were to refer to the war as

the "Fourteen Years' War of Resistance", reflecting a focus on the

broader conflict with Japan going back to the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

According to historian Rana Mitter, historians in China are unhappy with the

blanket revision, and (despite sustained tensions) the Republic of China did

not consider itself to be in an ongoing war with Japan over these six years. It

is also referred to as part of the "Global Anti-Fascist War".

In

contemporary Japan, the name "Japan–China War" is most commonly used

because of its perceived objectivity. When the invasion of China proper began

in earnest in July 1937 near Beijing, the government of Japan used "The

North China Incident", and with the outbreak of the Battle of Shanghai the

following month, it was changed to "The China Incident".

The

word "incident" was used by Japan, as neither country had made a

formal declaration of war. From the Japanese perspective, localizing these conflicts

was beneficial in preventing intervention from other countries, particularly

the United Kingdom and the United States, which were its primary source of

petroleum and steel respectively. A formal expression of these conflicts would

potentially lead to an American embargo in accordance with the Neutrality Acts

of the 1930s. In addition, due to China's fractured political status, Japan

often claimed that China was no longer a recognizable political entity on which

war could be declared.

Other Names

In

Japanese propaganda, the invasion of China became a crusade, the first step of

the "eight corners of the world under one roof" slogan. In 1940,

Japanese prime minister Fumimaro Konoe launched the Taisei Yokusankai. When

both sides formally declared war in December 1941, the name was replaced by

"Greater East Asia War".

Although

the Japanese government still uses the term "China Incident" in

formal documents, the word Shina is considered derogatory by China and

therefore the media in Japan often paraphrase with other expressions like

"The Japan–China Incident", which were used by media as early as the

1930s.

The

name "Second Sino-Japanese War" is not commonly used in Japan as the

China it fought a war against in 1894 to 1895 was led by the Qing dynasty, and

thus is called the Qing-Japanese War, rather than the First Sino-Japanese War.

Another

term for the second war between Japan and China is the "Japanese invasion

of China", a term used mainly in foreign and Chinese narratives.

Background

The

origins of the Second Sino-Japanese War can be traced to the First

Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), in which China, then under the rule of the Qing

dynasty, was defeated by Japan and forced to cede Taiwan and recognize the full

and complete independence of Korea in the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Japan also

annexed the Senkaku Islands, which Japan claims were uninhabited, in early 1895

as a result of its victory at the end of the war. Japan had also attempted to

annex the Liaodong Peninsula following the war, though was forced to return it

to China following the Triple Intervention by France, Germany, and Russia. The

Qing dynasty was on the brink of collapse due to internal revolts and the

imposition of the unequal treaties, while Japan had emerged as a great power

through its efforts to modernize. In 1905, Japan defeated the Russian Empire in

the Russo-Japanese War, gaining Dalian and southern Sakhalin and establishing a

protectorate over Korea.

Warlords in the Republic of China

In

1911, factions of the Qing Army uprose against the government, staging a revolution

that swept across China's southern provinces. The Qing responded by appointing

Yuan Shikai, commander of the loyalist Beiyang Army, as temporary prime

minister in order to subdue the revolution. Yuan, wanting to remain in power,

compromised with the revolutionaries, and agreed to abolish the monarchy and

establish a new republican government, under the condition he be appointed

president of China. The new Beiyang government of China was proclaimed in March

1912, after which Yuan Shikai began to amass power for himself. In 1913, the

parliamentary political leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated; it is generally

believed Yuan Shikai ordered the assassination. Yuan Shikai then forced the

parliament to pass a bill to strengthen the power of the president and sought

to restore the imperial system, becoming the new emperor of China.

However,

there was little support for an imperial restoration among the general population,

and protests and demonstrations soon broke out across the country. Yuan's attempts

at restoring the monarchy triggered the National Protection War, and Yuan

Shikai was overthrown after only a few months. In the aftermath of Shikai's

death in June 1916, control of China fell into the hands of the Beiyang Army

leadership. The Beiyang government was a civilian government in name, but in

practice it was a military dictatorship with a different warlord controlling

each province of the country. China was reduced to a fractured state. As a

result, China's prosperity began to wither and its economy declined. This

instability presented an opportunity for nationalistic politicians in Japan to

press for territorial expansion.

Twenty-One Demands

In

1915, Japan issued the Twenty-One Demands to extort further political and commercial

privilege from China, which was accepted by the regime of Yuan Shikai. Following

World War I, Japan acquired the German Empire's sphere of influence in Shandong

province, leading to nationwide anti-Japanese protests and mass demonstrations

in China. The country remained fragmented under the Beiyang Government and was

unable to resist foreign incursions. For the purpose of unifying China and

defeating the regional warlords, the Kuomintang (KMT) in Guangzhou launched the

Northern Expedition from 1926 to 1928 with limited assistance from the Soviet

Union.

Jinan Incident

The

National Revolutionary Army (NRA) formed by the Kuomintang swept through

southern and central China until it was checked in Shandong, where

confrontations with the Japanese garrison escalated into armed conflict. The

conflicts were collectively known as the Jinan incident of 1928, during which

time the Japanese military killed several Chinese officials and fired artillery

shells into Jinan. According to the investigation results of the Association of

the Families of the Victims of the Jinan massacre, it showed that 6,123 Chinese

civilians were killed and 1,701 injured. Relations between the Chinese

Nationalist government and Japan severely worsened as a result of the Jinan incident.

Reunification of China (1928)

As

the National Revolutionary Army approached Beijing, Zhang Zuolin decided to retreat

back to Manchuria, before he was assassinated by the Kwantung Army in 1928. His

son, Zhang Xueliang, took over as the leader of the Fengtian clique in

Manchuria. Later in the same year, Zhang declared his allegiance to the

Nationalist government in Nanjing under Chiang Kai-shek, and consequently,

China was nominally reunified under one government.

1929 Sino-Soviet war

The

July–November 1929 conflict over the Chinese Eastern Railroad (CER) further

increased the tensions in the Northeast that led to the Mukden Incident and

eventually the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Soviet Red Army victory over

Xueliang's forces not only reasserted Soviet control over the CER in Manchuria

but revealed Chinese military weaknesses that Japanese Kwantung Army officers

were quick to note.

The

Soviet Red Army performance also stunned the Japanese. Manchuria was central to

Japan's East Asia policy. Both the 1921 and 1927 Imperial Eastern Region Conferences

reconfirmed Japan's commitment to be the dominant power in the Northeast. The

1929 Red Army victory shook that policy to the core and reopened the Manchurian

problem. By 1930, the Kwantung Army realized they faced a Red Army that was

only growing stronger. The time to act was drawing near and Japanese plans to

conquer the Northeast were accelerated.

Chinese Communist Party

In

1930, the Central Plains War broke out across China, involving regional commanders

who had fought in alliance with the Kuomintang during the Northern Expedition,

and the Nanjing government under Chiang. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) previously

fought openly against the Nanjing government after the Shanghai massacre of 1927,

and they continued to expand during this protracted civil war. The Kuomintang

government in Nanjing decided to focus their efforts on suppressing the Chinese

Communists through the Encirclement Campaigns, following the policy of

"first internal pacification, then external resistance".

After

the defeat of the Chinese Soviet Republic by the Nationalists, the Communists

retreated on the Long March to Yan'an. The Nationalist government ordered

local warlords to continue the campaign against the Communists rather than

focus on the Japanese threat. A December 1936 coup by two Nationalist

Generals, the Xi'an Incident, forced Chiang Kai-shek to accept a United Front

with the Communists to oppose Japan.

Invasion of Manchuria and Northern China

The

internecine warfare in China provided excellent opportunities for Japan, which

saw Manchuria as a limitless supply of raw materials, a market for its

manufactured goods (now excluded from the markets of many Western countries as

a result of Depression-era tariffs), and a protective buffer state against the

Soviet Union in Siberia. As a result, the Japanese Army was widely prevalent in

Manchuria immediately following the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War

in 1905, where Japan gained significant territory in Manchuria. As a result of

their strengthened position, by 1915 Japan had negotiated a significant amount

of economic privilege in the region by pressuring Yuan Shikai, the president of

the Republic of China at the time. With a widened range of economic privileges

in Manchuria, Japan began focusing on developing and protecting matters of

economic interests. This included railroads, businesses, natural resources, and

a general control of the territory. With its influence growing, the Japanese

Army began to justify its presence by stating that it was simply protecting its

own economic interests. However militarists in the Japanese Army began pushing

for an expansion of influence, leading to the Japanese Army assassinating the

warlord of Manchuria, Zhang Zuolin. This was done with hopes that it would

start a crisis that would allow Japan to expand their power and influence in

the region. When this was not as successful as they desired, Japan then decided

to invade Manchuria outright after the Mukden incident in September 1931.

Japanese soldiers set off a bomb on the Southern Manchurian Railroad in order

to provoke an opportunity to act in "self defense" and invade

outright. Japan charged that its rights in Manchuria, which had been

established as a result of its victory in 1905 at the end of the Russo-Japanese

War, had been systematically violated and there were "more than 120 cases

of infringement of rights and interests, interference with business, boycott of

Japanese goods, unreasonable taxation, detention of individuals, confiscation

of properties, eviction, demand for cessation of business, assault and battery,

and the oppression of Korean residents".

After

five months of fighting, Japan established the puppet state of Manchukuo in

1932, and installed the last Emperor of China, Puyi, as its puppet ruler.

Militarily too weak to challenge Japan directly, China appealed to the League

of Nations for help. The League's investigation led to the publication of the

Lytton Report, condemning Japan for its incursion into Manchuria, causing Japan

to withdraw from the League of Nations. No country took action against Japan

beyond tepid censure. From 1931 until summer 1937, the Nationalist Army under

Chiang Kai-shek did little to oppose Japanese encroachment into China.

Incessant

fighting followed the Mukden Incident. In 1932, Chinese and Japanese troops

fought the 28 January battle. This resulted in the demilitarization of

Shanghai, which forbade the Chinese to deploy troops in their own city. In Manchukuo

there was an ongoing campaign to pacify the Anti-Japanese Volunteer Armies that

arose from widespread outrage over the policy of non-resistance to Japan. On 15

April 1932, the Chinese Soviet Republic led by the Communists declared war on

Japan.

In

1933, the Japanese attacked the Great Wall region. The Tanggu Truce established

in its aftermath, gave Japan control of Rehe Province, as well as a

demilitarized zone between the Great Wall and Beijing-Tianjin region. Japan

aimed to create another buffer zone between Manchukuo and the Chinese

Nationalist government in Nanjing.

Japan

increasingly exploited China's internal conflicts to reduce the strength of its

fractious opponents. Even years after the Northern Expedition, the political

power of the Nationalist government was limited to just the area of the Yangtze

River Delta. Other sections of China were essentially in the hands of local

Chinese warlords. Japan sought various Chinese collaborators and helped them

establish governments friendly to Japan. This policy was called the

Specialization of North China, more commonly known as the North China

Autonomous Movement. The northern provinces affected by this policy were

Chahar, Suiyuan, Hebei, Shanxi, and Shandong.

This

Japanese policy was most effective in the area of what is now Inner Mongolia

and Hebei. In 1935, under Japanese pressure, China signed the He–Umezu

Agreement, which forbade the KMT to conduct party operations in Hebei. In the

same year, the Chin–Doihara Agreement was signed expelling the KMT from Chahar.

Thus, by the end of 1935 the Chinese government had essentially abandoned

northern China. In its place, the Japanese-backed East Hebei Autonomous Council

and the Hebei–Chahar Political Council were established. There in the empty

space of Chahar the Mongol military government was formed on 12 May 1936. Japan

provided all the necessary military and economic aid. Afterwards Chinese

volunteer forces continued to resist Japanese aggression in Manchuria, and

Chahar and Suiyuan.

Some

Chinese historians believe the 18 September 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria

marks the start of the War of Resistance. Although not the conventional Western

view, British historian Rana Mitter describes this Chinese trend of historical

analysis as "perfectly reasonable". In 2017, the Chinese government

officially announced that it would adopt this view. Under this interpretation,

the 1931–1937 period is viewed as the "partial" war, while 1937–1945

is a period of "total" war. This view of a fourteen-year war has

political significance because it provides more recognition for the role of

northeast China in the War of Resistance.

1937:

Full-scale invasion of China

On

the night of 7 July 1937, Chinese and Japanese troops exchanged fire in the

vicinity of the Marco Polo (or Lugou) Bridge about 16 km from Beijing. The

initial confused and sporadic skirmishing soon escalated into a full-scale

battle.

Unlike

Japan, China was unprepared for total war and had little military-industrial

strength, no mechanized divisions, and few armored forces.

Within

the first year of full-scale war, Japanese forces obtained victories in most major

Chinese cities.

Battle of Beiping–Tianjin

On

11 July, in accordance with the Goso conference, the Imperial Japanese Army

General Staff authorized the deployment of an infantry division from the Chōsen

Army, two combined brigades from the Kwantung Army and an air regiment composed

of 18 squadrons as reinforcements to Northern China. By 20 July, total Japanese

military strength in the Beijing-Tianjin area exceeded 180,000 personnel.

The

Japanese gave Sung and his troops "free passage" before moving in to

pacify resistance in areas surrounding Beijing (then Beiping) and Tianjin.

After 24 days of combat, the Chinese 29th Army was forced to withdraw. The

Japanese captured Beijing and the Taku Forts at Tianjin on 29 and 30 July

respectively, thus concluding the Beijing-Tianjin campaign. By August 1937,

Japan had occupied Beijing and Tianjin.

However,

the Japanese Army had been given orders not to advance further than the Yongding

River. In a sudden volte-face, the Konoe government's foreign minister opened

negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek's government in Nanjing and stated:

"Japan wants Chinese cooperation, not Chinese land." Nevertheless,

negotiations failed to move further. The Ōyama Incident on 9 August escalated

the skirmishes and battles into full scale warfare.

The

29th Army's resistance (and poor equipment) inspired the 1937 "Sword

March", which—with slightly reworked lyrics—became the National

Revolutionary Army's standard marching cadence and popularized the racial

epithet guizi to describe the Japanese invaders.

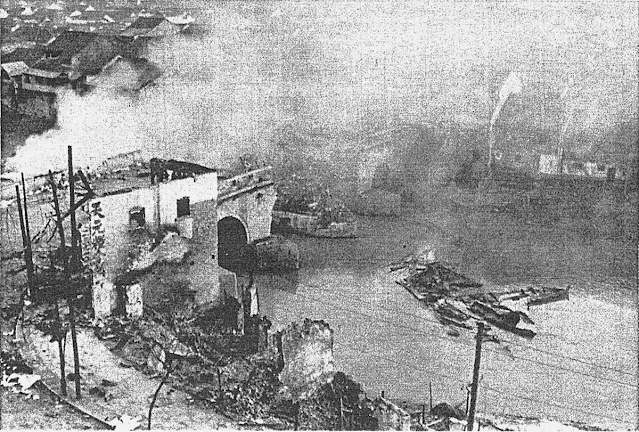

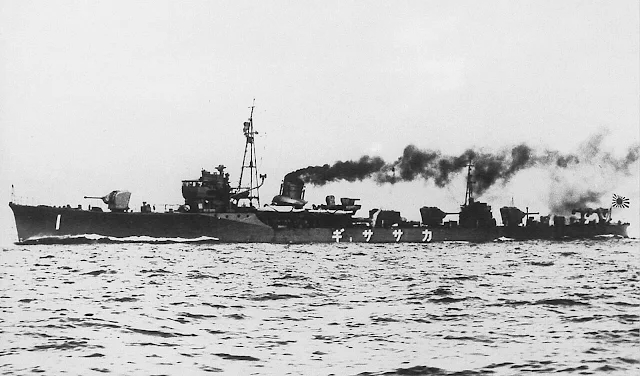

Battle of Shanghai

The

Imperial General Headquarters (GHQ) in Tokyo, content with the gains acquired

in northern China following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, initially showed

reluctance to escalate the conflict into a full-scale war. Following the shooting

of two Japanese officers who were attempting to enter the Hongqiao military

airport on 9 August 1937, the Japanese demanded that all Chinese forces withdraw

from Shanghai; the Chinese outright refused to meet this demand. In response,

both the Chinese and the Japanese marched reinforcements into the Shanghai area.

Chiang concentrated his best troops north of Shanghai in an effort to impress

the city's large foreign community and increase China's foreign support.

On

13 August 1937, Kuomintang soldiers attacked Japanese Marine positions in

Shanghai, with Japanese army troops and marines in turn crossing into the city

with naval gunfire support at Zhabei, leading to the Battle of Shanghai. On 14

August, Chinese forces under the command of Zhang Zhizhong were ordered to

capture or destroy the Japanese strongholds in Shanghai, leading to bitter

street fighting. In an attack on the Japanese cruiser Izumo, Kuomintang planes

accidentally bombed the Shanghai International Settlement, which led to more

than 3,000 civilian deaths.

In

the three days from 14 to 16 August 1937, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) sent

many sorties of the then-advanced long-ranged G3M medium-heavy land-based

bombers and assorted carrier-based aircraft with the expectation of destroying

the Chinese Air Force. However, the Imperial Japanese Navy encountered

unexpected resistance from the defending Chinese Curtiss Hawk II/Hawk III and

P-26/281 Peashooter fighter squadrons; suffering heavy (50%) losses from the

defending Chinese pilots (14 August was subsequently commemorated by the KMT as

China's Air Force Day).

The

skies of China had become a testing zone for advanced biplane and new-generation

monoplane combat-aircraft designs. The introduction of the advanced A5M

"Claude" fighters into the Shanghai-Nanjing theater of operations,

beginning on 18 September 1937, helped the Japanese achieve a certain level of

air superiority. However the few experienced Chinese veteran pilots, as well as

several Chinese-American volunteer fighter pilots, including Maj. Art Chin,

Maj. John Wong Pan-yang, and Capt. Chan Kee-Wong, even in their older and

slower biplanes, proved more than able to hold their own against the sleek A5Ms

in dogfights, and it also proved to be a battle of attrition against the

Chinese Air Force. At the start of the battle, the local strength of the NRA

was around five divisions, or about 70,000 troops, while local Japanese forces

comprised about 6,300 marines. On 23 August, the Chinese Air Force attacked

Japanese troop landings at Wusongkou in northern Shanghai with Hawk III

fighter-attack planes and P-26/281 fighter escorts, and the Japanese intercepted

most of the attack with A2N and A4N fighters from the aircraft carriers Hosho

and Ryujo, shooting down several of the Chinese planes while losing a single

A4N in the dogfight with Lt. Huang Xinrui in his P-26/281; the Japanese Army

reinforcements succeeded in landing in northern Shanghai. The Imperial Japanese

Army (IJA) ultimately committed over 300,000 troops, along with numerous naval

vessels and aircraft, to capture the city. After more than three months of

intense fighting, their casualties far exceeded initial expectations. On 26 October,

the IJA captured Dachang, a key strong-point within Shanghai, and on 5

November, additional reinforcements from Japan landed in Hangzhou Bay. Finally,

on 9 November, the NRA began a general retreat.

Japan

did not immediately occupy the Shanghai International Settlement or the

Shanghai French Concession, areas which were outside of China's control due to

the treaty port system. Japan moved into these areas after its 1941 declaration

of war against the United States and the United Kingdom.

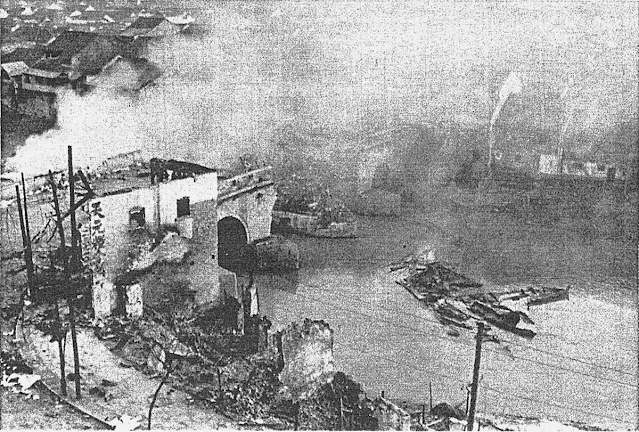

Battle of Nanjing and Massacre

In

November 1937, the Japanese concentrated 220,000 soldiers and began a campaign

against Nanjing. Building on the hard-won victory in Shanghai, the IJA

advanced on and captured the KMT capital city of Nanjing (December 1937) and

Northern Shanxi (September – November 1937).

Japanese

forces inflicted heavy casualties on the Chinese soldiers defending the city,

killing approximately 50,000 of them including 17 Chinese generals. Upon the

capture of Nanjing, Japanese committed massive war atrocities including mass

murder and rape of Chinese civilians after 13 December 1937, which has been

referred to as the Nanjing Massacre. Over the next several weeks, Japanese

troops perpetrated numerous mass executions and tens of thousands of rapes. The

army looted and burned the surrounding towns and the city, destroying more than

a third of the buildings.

The

number of Chinese killed in the massacre has been subject to much debate, with

estimates ranging from 100,000 to more than 300,000. The numbers agreed upon by

most scholars are provided by the International Military Tribunal for the Far

East, which estimate at least 200,000 murders and 20,000 rapes.

The

Japanese atrocities in Nanjing, especially following the Chinese defense of

Shanghai, increased international goodwill for the Chinese people and the

Chinese government.

The

Nationalist government re-established itself in Chongqing, which became the wartime

seat of government until 1945.

1938

By

January 1938, most conventional Kuomintang forces had either been defeated or

no longer offered major resistance to Japanese advances. KMT forces won a few

victories in 1938 (the Battle of Taierzhuang and the Battle of Wanjialing) but

were generally ineffective that year. By March 1938, the Japanese controlled

almost all of North China. Communist-led rural resistance to the Japanese

remained active, however.

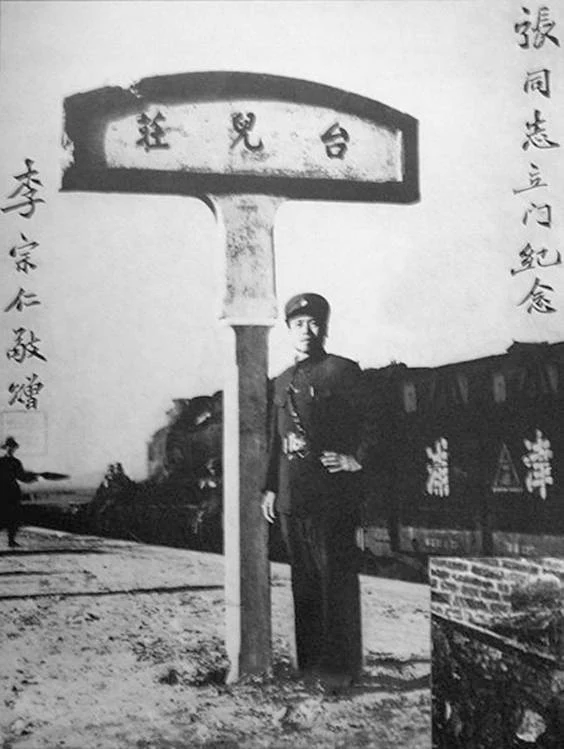

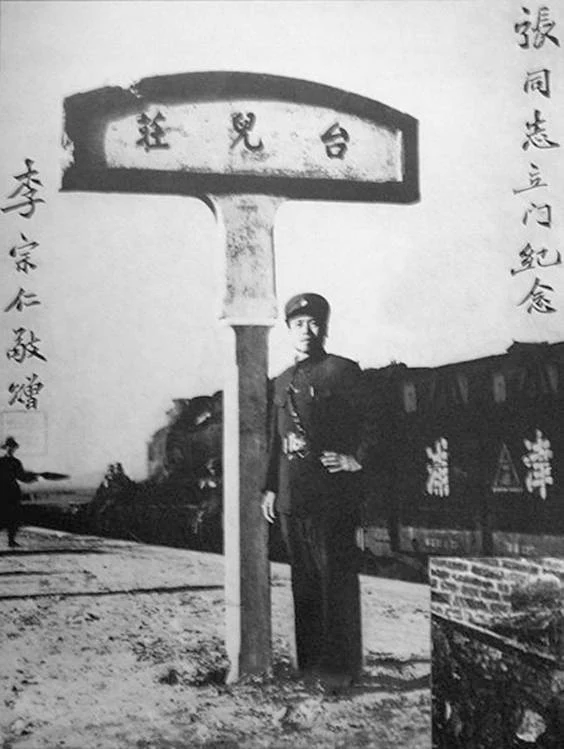

Battles of Xuzhou and Taierzhuang

With

many victories achieved, Japanese field generals escalated the war in Jiangsu

in an attempt to wipe out the Chinese forces in the area. The Japanese managed

to overcome Chinese resistance around Bengbu and the Teng xian, but were fought

to a halt at Linyi.

The

Japanese were then decisively defeated at the Battle of Taierzhuang

(March–April 1938), where the Chinese used night attacks and close-quarters

combat to overcome Japanese advantages in firepower. The Chinese also severed

Japanese supply lines from the rear, forcing the Japanese to retreat in the

first Chinese victory of the war.

The

Japanese then attempted to surround and destroy the Chinese armies in the Xuzhou

region with an enormous pincer movement. However the majority of the Chinese

forces, some 200,000–300,000 troops in 40 divisions, managed to break out of

the encirclement and retreat to defend Wuhan, the Japanese's next target.

Battle of Wuhan

Following

Xuzhou, the IJA changed its strategy and deployed almost all of its existing

armies in China to attack the city of Wuhan, which had become the political,

economic and military center of China, in hopes of destroying the fighting

strength of the NRA and forcing the KMT government to negotiate for peace. On 6

June, they captured Kaifeng, the capital of Henan, and threatened to take

Zhengzhou, the junction of the Pinghan and Longhai railways.

The

Japanese forces, numbering some 400,000 men, were faced by over 1 million NRA

troops in the Central Yangtze region. Having learned from their defeats at

Shanghai and Nanjing, the Chinese had adapted themselves to fight the Japanese

and managed to check their forces on many fronts, slowing and sometimes

reversing the Japanese advances, as in the case of Wanjialing.

To

overcome Chinese resistance, Japanese forces frequently deployed poison gas and

committed atrocities against civilians, such as a "mini-Nanjing

Massacre" in the city of Jiujiang upon its capture. After four months of

intense combat, the Nationalists were forced to abandon Wuhan by October, and

its government and armies retreated to Chongqing. Both sides had suffered tremendous

casualties in the battle, with the Chinese losing up to 500,000 soldiers killed

or wounded, and the Japanese up to 200,000.

Communist Resistance

After

their victory at Wuhan, Japan advanced deep into Communist territory and redeployed

50,000 troops to the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei Border Region. Elements of the Eighth

Route Army soon attacked the advancing Japanese, inflicting between 3,000 and

5,000 casualties and resulting in a Japanese retreat. The Eighth Route Army carried

out guerilla operations and established military and political bases. As the

Japanese military came to understand that the Communists avoided conventional

attacks and defense, it altered its tactics. The Japanese military built more

roads to quicken movement between strongpoints and cities, blockaded rivers and

roads in an effort to disrupt Communists supply, sought to expand militia from

its puppet regime to conserve manpower, and use systematic violence on

civilians in the Border Region in an effort to destroy its economy. The

Japanese military mandated confiscation of the Eighth Route Army's goods and

used this directive as a pretext to confiscate goods, including engaging in

grave robbery in the Border Region.

With

Japanese casualties and costs mounting, the Imperial General Headquarters attempted

to break Chinese resistance by ordering the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

and Imperial Japanese Army Air Service to launch the war's first massive air

raids on civilian targets. Japanese raiders hit the Kuomintang's newly

established provisional capital of Chongqing and most other major cities in

unoccupied China, leaving many people either dead, injured, or homeless.

Yellow River Flood

The

1938 Yellow River flood was a man-made flood from June 1938 to January 1947

created by the intentional destruction of levees on the Yellow River in

Huayuankou, Henan by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) during the Second

Sino-Japanese War. The first wave of floods hit Zhongmu County on 13 June 1938.

NRA

commanders intended the flood to act as a scorched earth defensive line against

the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces. There were three long-term strategic

intentions behind the decision to cause the flooding: firstly, the flood in

Henan safeguarded the Guanzhong section of the Longhai railway, a major

northwestern route used by the Soviet Union to send supplies to the NRA from

August 1937 to March 1941. Secondly, the flooding of significant portions of

land and railway sections made it difficult for the Japanese military to enter

Shaanxi, thereby preventing them from invading the Sichuan basin, where the

Chinese wartime capital of Chongqing and China's southwestern home front were

located. Thirdly, the floods in Henan and Anhui destroyed much of the tracks

and bridges of the Beijing–Wuhan railway, the Tianjin–Pukou railway and the

Longhai railway, thereby preventing the Japanese from effectively moving their

forces across Northern and Central China. In the short term, the NRA aimed to

use the flood to halt the rapid transit of Japanese units from Northern China

to areas near Wuhan.

1939–1943

By

1939, the Nationalist army had withdrawn to the southwest and northwest of

China and the Japanese controlled the coastal cities that been centres of

Nationalist power. From 1939 to 1945, China was divided into three regions:

Japanese-occupied territories (Lunxianqu), the Nationalist-controlled region

(Guotongqu), and the Communist-controlled regions (Jiefangqu, or liberated

areas).

From

the beginning of 1939, the war entered a new phase with the unprecedented defeat

of the Japanese at Battle of Suixian–Zaoyang and First Battle of Changsha.

In

1939, Mao Zedong wrote The Greatest Crisis under Current Conditions, calling

for more active resistance against Japan and for the strengthening of the

Second United Front.

The

Chinese launched their first large-scale counter-offensive against the IJA in December

1939; however, due to its low military-industrial capacity and limited experience

in modern warfare, this offensive was defeated. Afterwards Chiang could not

risk any more all-out offensive campaigns given the poorly trained,

under-equipped, and disorganized state of his armies and opposition to his

leadership both within the Kuomintang and in China in general. He had lost a

substantial portion of his best trained and equipped troops in the Battle of

Shanghai and was at times at the mercy of his generals, who maintained a high

degree of autonomy from the central KMT government.

During

the offensive, Hui forces in Suiyuan under generals Ma Hongbin and Ma Buqing

routed the Imperial Japanese Army and their puppet Inner Mongol forces and

prevented the planned Japanese advance into northwest China. Ma Hongbin's

father Ma Fulu had fought against Japanese in the Boxer Rebellion. General Ma

Biao led Hui, Salar and Dongxiang cavalry to defeat the Japanese at the Battle

of Huaiyang. Ma Biao fought against the Japanese in the Boxer Rebellion.

After

1940, the Japanese encountered tremendous difficulties in administering and

garrisoning the seized territories, and tried to solve their occupation

problems by implementing a strategy of creating friendly puppet governments favorable

to Japanese interests in the territories conquered. This included prominently

the regime headed by Wang Jingwei, one of Chiang's rivals in the KMT. However,

atrocities committed by the Imperial Japanese Army, as well as Japanese refusal

to delegate any real power, left the puppets very unpopular and largely

ineffective. The only success the Japanese had was to recruit a large

Collaborationist Chinese Army to maintain public security in the occupied

areas.

Japanese Expansion

By

1941, Japan held most of the eastern coastal areas of China and Vietnam, but

guerrilla fighting continued in these occupied areas. Japan had suffered high

casualties which resulted from unexpectedly stubborn Chinese resistance, and

neither side could make any swift progress in the manner of Nazi Germany in

Western Europe.

By

1943, Guangdong had experienced famine. As the situation worsened, New York

Chinese compatriots received a letter stating that 600,000 people were killed

in Siyi by starvation.

Second Phase: October 1938 – December

1941

During

this period, the main Chinese objective was to drag out the war for as long as

possible in a war of attrition, thereby exhausting Japanese resources while it

was building up China's military capacity. American general Joseph Stilwell

called this strategy "winning by outlasting". The NRA adopted the

concept of "magnetic warfare" to attract advancing Japanese troops to

definite points where they were subjected to ambush, flanking attacks, and

encirclements in major engagements. The most prominent example of this tactic

was the successful defense of Changsha in 1939, and again in the 1941 battle,

in which heavy casualties were inflicted on the IJA.

Local

Chinese resistance forces, organized separately by both the CCP and the KMT,

continued their resistance in occupied areas to make Japanese administration

over the vast land area of China difficult. In 1940, the Chinese Red Army

launched a major offensive in north China, destroying railways and a major coal

mine. These constant guerilla and sabotage operations deeply frustrated the

Imperial Japanese Army and they led them to employ the Three Alls policy—kill

all, loot all, burn all. It was during this period that the bulk of Japanese

war crimes were committed.

By

1941, Japan had occupied much of north and coastal China, but the KMT central

government and military had retreated to the western interior to continue their

resistance, while the Chinese communists remained in control of base areas in

Shaanxi. In the occupied areas, Japanese control was mainly limited to

railroads and major cities ("points and lines"). They did not have a

major military or administrative presence in the vast Chinese countryside,

where Chinese guerrillas roamed freely.

From

1941 to 1942, Japan concentrated most of its forces in China in an effort to defeat

the Communist bases behind Japan's lines. To decrease guerilla's human and material

resources, the Japanese military implemented its Three Alls policy ("Kill

all, loot all, burn all"). In response, the Communist armies increased

their role in production activities, including farming, raising hogs, and

cloth-making.

Relationship Between the Nationalists and the Communists

After

the Mukden Incident in 1931, Chinese public opinion was strongly critical of

Manchuria's leader, the "young marshal" Zhang Xueliang, for his

non-resistance to the Japanese invasion, even though the Kuomintang central

government was also responsible for this policy, giving Zhang an order to

improvise while not offering support. After losing Manchuria to the Japanese,

Zhang and his Northeast Army were given the duty of suppressing the Red Army in

Shaanxi after their Long March. This resulted in great casualties for his

Northeast Army, which received no support in manpower or weaponry from Chiang

Kai-shek.

In

the Xi'an Incident that took place on 12 December 1936, Zhang Xueliang kidnapped

Chiang Kai-shek in Xi'an, hoping to force an end to KMT–CCP conflict. To secure

the release of Chiang, the KMT agreed to a temporary ceasefire with the Communists.

On 24 December, the two parties agreed to a United Front against Japan; this

had salutary effects for the beleaguered Communists, who agreed to form the New

Fourth Army and the 8th Route Army under the nominal control of the NRA. In addition,

Shaan-Gan-Ning and Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei border regions were created, under the

control of the CCP. In Shaan-Gan-Ning, Communists in the Shaan-Gan-Ning Base

Area fostered opium production, taxed it, and engaged in its trade—including

selling to Japanese-occupied and KMT-controlled provinces. The Red Army fought

alongside KMT forces during the Battle of Taiyuan, and the high point of their

cooperation came in 1938 during the Battle of Wuhan.

The

formation of a united front added to the legality of the CCP, but what kind of

support the central government would provide to the communists were not settled.

When compromise with the CCP failed to incentivize the Soviet Union to engage

in an open conflict against Japan, the KMT withheld further support for the

Communists. To strengthen their legitimacy, Communist forces actively engaged

the Japanese early on. These operations weakened Japanese forces in Shanxi and

other areas in the North. Mao Zedong was distrustful of Chiang Kai-shek, however,

and shifted strategy to guerrilla warfare in order to preserve the CCP's

military strength.

Despite

Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions, and

the rich Yangtze River Valley in central China, the distrust between the two

antagonists was scarcely veiled. The uneasy alliance began to break down by

late 1938, partially due to the Communists' aggressive efforts to expand their

military strength by absorbing Chinese guerrilla forces behind Japanese lines.

Chinese militia who refused to switch their allegiance were often labeled

"collaborators" and attacked by CCP forces. For example, the Red Army

led by He Long attacked and wiped out a brigade of Chinese militia led by Zhang

Yin-wu in Hebei in June 1939. Starting in 1940, open conflict between

Nationalists and Communists became more frequent in the occupied areas outside

of Japanese control, culminating in the New Fourth Army Incident in January

1941.

Afterwards,

the Second United Front completely broke down and Chinese Communists leader Mao

Zedong outlined the preliminary plan for the CCP's eventual seizure of power

from Chiang Kai-shek. Mao himself is quoted outlining the "721" policy,

saying "We are fighting 70 percent for self development, 20 percent for

compromise, and 10 percent against Japan". Mao began his final push for

consolidation of CCP power under his authority, and his teachings became the

central tenets of the CCP doctrine that came to be formalized as Mao Zedong

Thought. The Communists also began to focus most of their energy on building up

their sphere of influence wherever opportunities were presented, mainly through

rural mass organizations, administrative, land and tax reform measures favoring

poor peasants; while the Nationalists attempted to neutralize the spread of

Communist influence by military blockade of areas controlled by CCP and

fighting the Japanese at the same time.

Entrance of the Western Allies

Japan

had expected to extract economic benefits of its invasions of China and elsewhere,

including in the form of fuel and raw material resources. As Japanese aggression

continued, however, the United States responded with trade embargoes on various

goods, including oil and petroleum (beginning December 1939) and scrap iron and

munitions (beginning July 1940). The United States demanded that Japan

withdraw from China and also refused to recognize Japan's occupations of the

Indochinese countries. In spring 1941, trade negotiations between the United

States and Japan failed. In July 1941, the United States froze Japanese

financial assets and obtained Dutch and British agreements to also cut those

countries' oil exports to Japan. This in turn prompted the Japanese decision

to attack Pearl Harbor.

Following

the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war against Japan, and

within days China joined the Allies in formal declaration of war against Japan,

Germany and Italy. As the Western Allies entered the war against Japan, the

Sino-Japanese War would become part of a greater conflict, the Pacific theatre

of World War II. Japan's military action against the United States also

restrained its capacity to conduct further offensive operations in China.

After

the Lend-Lease Act was passed in 1941, American financial and military aid began

to trickle in. Claire Lee Chennault commanded the 1st American Volunteer Group

(nicknamed the Flying Tigers), with American pilots flying American warplanes

which were painted with the Chinese flag to attack the Japanese. He headed both

the volunteer group and the uniformed U.S. Army Air Forces units that replaced

it in 1942. However, it was the Soviets that provided the greatest material

help for China from 1937 into 1941, with fighter aircraft for the Nationalist

Chinese Air Force and artillery and armor for the Chinese Army through the

Sino-Soviet Treaty; Operation Zet also provided for a group of Soviet volunteer

combat aviators to join the Chinese Air Force in the fight against the Japanese

occupation from late 1937 through 1939. The United States embargoed Japan in

1941 depriving it of shipments of oil and various other resources necessary to

continue the war in China. This pressure, which was intended to disparage a

continuation of the war and bring Japan into negotiation, resulted in the

Attack on Pearl Harbor and Japan's drive south to procure from the resource-rich

European colonies in Southeast Asia by force the resources which the United

States had denied to them.

Almost

immediately, Chinese troops achieved another decisive victory in the Battle of

Changsha, which earned the Chinese government much prestige from the Western Allies.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to the United States, United Kingdom,

Soviet Union and China as the world's "Four Policemen"; his primary

reason for elevating China to such a status was the belief that after the war

it would serve as a bulwark against the Soviet Union.

Knowledge

of Japanese naval movements in the Pacific was provided to the American Navy by

the Sino-American Cooperative Organization (SACO) which was run by the Chinese

intelligence head Dai Li. Philippine and Japanese ocean weather was affected by

weather originating near northern China. The base of SACO was located in

Yangjiashan.

Chiang

Kai-shek continued to receive supplies from the United States. However, in

contrast to the Arctic supply route to the Soviet Union which stayed open

through most of the war, sea routes to China and the Yunnan–Vietnam Railway had

been closed since 1940. Therefore, between the closing of the Burma Road in

1942 and its re-opening as the Ledo Road in 1945, foreign aid was largely

limited to what could be flown in over "The Hump". In Burma, on 16

April 1942, 7,000 British soldiers were encircled by the Japanese 33rd Division

during the Battle of Yenangyaung and rescued by the Chinese 38th Division.

After the Doolittle Raid, the Imperial Japanese Army conducted a massive sweep

through Zhejiang and Jiangxi, now known as the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Campaign, with

the goal of finding the surviving American airmen, applying retribution on the

Chinese who aided them and destroying air bases. The operation started 15 May

1942, with 40 infantry battalions and 15–16 artillery battalions but was

repelled by Chinese forces in September. During this campaign, the Imperial

Japanese Army left behind a trail of devastation and also spread cholera,

typhoid, plague and dysentery pathogens. Chinese estimates allege that as many

as 250,000 civilians, the vast majority of whom were destitute Tanka boat

people and other pariah ethnicities unable to flee, may have died of disease.

It caused more than 16 million civilians to evacuate far away deep inward

China. 90% of Ningbo's population had already fled before battle started.

Most

of China's industry had already been captured or destroyed by Japan, and the Soviet

Union refused to allow the United States to supply China through the Kazakhstan

into Xinjiang as the Xinjiang warlord Sheng Shicai had turned anti-Soviet in

1942 with Chiang's approval. For these reasons, the Chinese government never

had the supplies and equipment needed to mount major counter-offensives.

Despite the severe shortage of matériel, in 1943, the Chinese were successful

in repelling major Japanese offensives in Hubei and Changde.

Chiang

was named Allied commander-in-chief in the China theater in 1942. American

general Joseph Stilwell served for a time as Chiang's chief of staff, while

simultaneously commanding American forces in the China-Burma-India Theater. For

many reasons, relations between Stilwell and Chiang soon broke down. Many

historians (such as Barbara W. Tuchman) have suggested it was largely due to

the corruption and inefficiency of the Kuomintang government, while others

(such as Ray Huang and Hans van de Ven) have depicted it as a more complicated

situation. Stilwell had a strong desire to assume total control of Chinese

troops and pursue an aggressive strategy, while Chiang preferred a patient and

less expensive strategy of out-waiting the Japanese. Chiang continued to

maintain a defensive posture despite Allied pleas to actively break the

Japanese blockade, because China had already suffered tens of millions of war

casualties and believed that Japan would eventually capitulate in the face of

America's overwhelming industrial output. For these reasons the other Allies

gradually began to lose confidence in the Chinese ability to conduct offensive

operations from the Asian mainland, and instead concentrated their efforts

against the Japanese in the Pacific Ocean Areas and South West Pacific Area,

employing an island hopping strategy.

Long-standing

differences in national interest and political stance among China, the United

States, and the United Kingdom remained in place. British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill was reluctant to devote British troops, many of whom had been

routed by the Japanese in earlier campaigns, to the reopening of the Burma

Road; Stilwell, on the other hand, believed that reopening the road was vital,

as all China's mainland ports were under Japanese control. The Allies' "Europe

first" policy did not sit well with Chiang, while the later British

insistence that China send more and more troops to Indochina for use in the

Burma Campaign was seen by Chiang as an attempt to use Chinese manpower to

defend British colonial possessions. Chiang also believed that China should

divert its crack army divisions from Burma to eastern China to defend the

airbases of the American bombers that he hoped would defeat Japan through

bombing, a strategy that American general Claire Lee Chennault supported but

which Stilwell strongly opposed. In addition, Chiang voiced his support of the

Indian independence movement in a 1942 meeting with Mohandas Gandhi, which

further soured the relationship between China and the United Kingdom.

American

and Canadian-born Chinese were recruited to act as covert operatives in

Japanese-occupied China. Employing their racial background as a disguise, their

mandate was to blend in with local citizens and wage a campaign of sabotage.

Activities focused on destruction of Japanese transportation of supplies

(signaling bomber destruction of railroads, bridges). Chinese forces advanced

to northern Burma in late 1943, besieged Japanese troops in Myitkyina, and

captured Mount Song. The British and Commonwealth forces had their operation in

Mission 204 which attempted to provide assistance to the Chinese Nationalist

Army. The first phase in 1942 under command of SOE achieved very little, but lessons

were learned and a second more successful phase, commenced in February 1943

under British Military command, was conducted before the Japanese Operation

Ichi-Go offensive in 1944 compelled evacuation.

1944

and Operation Ichi-Go

In

1944, the Communists launched counteroffensives from the liberated areas

against Japanese forces.

Japan's

1944 Operation Ichi-Go was the largest military campaign of the Second

Sino-Japanese War. The campaign mobilized 500,000 Japanese troops, 100,000

horses, 1,500 artillery pieces, and 800 tanks. The 750,000 casualty figure for

Nationalist Chinese forces are not all dead and captured, Cox included in the

750,000 casualties that China incurred in Ichigo soldiers who simply

"melted away" and others who were rendered combat ineffective besides

killed and captured soldiers.

In

late November 1944, the Japanese advance slowed approximately 300 miles from

Chongqing as it experienced shortages of trained soldiers and materiel.

Although Operation Ichi-Go achieved its goals of seizing United States air

bases and establishing a potential railway corridor from Manchukuo to Hanoi, it

did so too late to impact the result of the broader war. American bombers in

Chengdu were moved to the Mariana Islands where, along with bombers from bases

in Saipan and Tinian, they could still bomb the Japanese home islands.

After

Operation Ichigo, Chiang Kai-shek started a plan to withdraw Chinese troops

from the Burma theatre against Japan in Southeast Asia for a counter offensive

called "White Tower" and "Iceman" against Japanese soldiers

in China in 1945.

The

poor performance of Chiang Kai-shek's forces in opposing the Japanese advance

during Operation Ichigo became widely viewed as demonstrating Chiang's incompetence.

It irreparably damaged the Roosevelt administration's view of Chiang and the

KMT. The campaign further weakened the Nationalist economy and government revenues.

Because of the Nationalists' increasing inability to fund the military,

Nationalist authorities overlooked military corruption and smuggling. The

Nationalist army increasingly turned to raiding villages to press-gang peasants

into service and force marching them to assigned units. Approximately 10% of

these peasants died before reaching their units.

By

the end of 1944, Chinese troops under the command of Sun Li-jen attacking from

India, and those under Wei Lihuang attacking from Yunnan, joined forces in

Mong-Yu, successfully driving the Japanese out of North Burma and securing the

Ledo Road, China's vital supply artery. In Spring 1945 the Chinese launched

offensives that retook Hunan and Guangxi. With the Chinese army progressing

well in training and equipment, Wedemeyer planned to launch Operation Carbonado

in summer 1945 to retake Guangdong, thus obtaining a coastal port, and from

there drive northwards toward Shanghai. However, the atomic bombings of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Soviet invasion of Manchuria hastened Japanese

surrender and these plans were not put into action.

Foreign

Aid

Before

the start of full-scale warfare of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Germany had

since the time of the Weimar Republic, provided much equipment and training to

crack units of the National Revolutionary Army of China, including some

aerial-combat training with the Luftwaffe to some pilots of the pre-Nationalist

Air Force of China. A number of foreign powers, including the Americans,

Italians and Japanese, provided training and equipment to different air force

units of pre-war China. With the outbreak of full-scale war between China and

the Empire of Japan, the Soviet Union became the primary supporter for China's

war of resistance through the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact from 1937 to

1941. When the Imperial Japanese invaded French Indochina, the United States enacted

the oil and steel embargo against Japan and froze all Japanese assets in 1941,

and with it came the Lend-Lease Act of which China became a beneficiary on 6

May 1941; from there, China's main diplomatic, financial and military supporter

came from the U.S., particularly following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Overseas Chinese

Over

3,200 overseas Chinese drivers and motor vehicle mechanics embarked to wartime

China to support military and logistics supply lines, especially through

Indo-China, which became of absolute tantamount importance when the Japanese

cut-off all ocean-access to China's interior with the capture of Nanning after

the Battle of South Guangxi. Overseas Chinese communities in the U.S. raised

money and nurtured talent in response to Imperial Japan's aggressions in China,

which helped to fund an entire squadron of Boeing P-26 fighter planes purchased

for the looming war situation between China and the Empire of Japan; over a

dozen Chinese-American aviators, including John "Buffalo" Huang,

Arthur Chin, Hazel Ying Lee, Chan Kee-Wong et al., formed the original

contingent of foreign volunteer aviators to join the Chinese air forces (some

provincial or warlord air forces, but ultimately all integrating into the

centralized Chinese Air Force; often called the Nationalist Air Force of China)

in the "patriotic call to duty for the motherland" to fight against

the Imperial Japanese invasion. Several of the original Chinese-American

volunteer pilots were sent to Lagerlechfeld Air Base in Germany for

aerial-gunnery training by the Chinese Air Force in 1936.

German

Prior

to the war, Germany and China were in close economic and military cooperation,

with Germany helping China modernize its industry and military in exchange for

raw materials. Germany sent military advisers such as Alexander von

Falkenhausen to China to help the KMT government reform its armed forces. Some

divisions began training to German standards and were to form a relatively

small but well trained Chinese Central Army. By the mid-1930s about 80,000

soldiers had received German-style training. After the KMT lost Nanjing and

retreated to Wuhan, Hitler's government decided to withdraw its support of

China in 1938 in favour of an alliance with Japan as its main anti-Communist

partner in East Asia.

Soviet

After

Germany and Japan signed the anti-communist Anti-Comintern Pact, the Soviet

Union hoped to keep China fighting, in order to deter a Japanese invasion of

Siberia and save itself from a two-front war. In September 1937, they signed

the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact and approved Operation Zet, the formation

of a secret Soviet volunteer air force, in which Soviet technicians upgraded

and ran some of China's transportation systems. Bombers, fighters, supplies and

advisors arrived, headed by Aleksandr Cherepanov. Prior to the Western Allies,

the Soviets provided the most foreign aid to China: some $250 million in

credits for munitions and other supplies. The Soviet Union defeated Japan in

the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in May – September 1939, leaving the Japanese

reluctant to fight the Soviets again. In April 1941, Soviet aid to China ended

with the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact and the beginning of the Great

Patriotic War. This pact enabled the Soviet Union to avoid fighting against

Germany and Japan at the same time. In August 1945, the Soviet Union annulled

the neutrality pact with Japan and invaded Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, the Kuril

Islands, and northern Korea. The Soviets also continued to support the Chinese

Communist Party. In total, 3,665 Soviet advisors and pilots served in China,

and 227 of them died fighting there.

The

Soviet Union provided financial aid to both the Communists and the

Nationalists.

United States

The

United States generally avoided taking sides between Japan and China until

1940, providing virtually no aid to China in this period. For instance, the

1934 Silver Purchase Act signed by President Roosevelt caused chaos in China's

economy which helped the Japanese war effort. The 1933 Wheat and Cotton Loan

mainly benefited American producers, while aiding to a smaller extent both

Chinese and Japanese alike. This policy was due to US fear of breaking off

profitable trade ties with Japan, in addition to US officials and businesses

perception of China as a potential source of massive profit for the US by

absorbing surplus American products, as William Appleman Williams states.

From

December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS Panay and the Nanjing

Massacre swung public opinion in the West sharply against Japan and increased

their fear of Japanese expansion, which prompted the United States, the United

Kingdom, and France to provide loan assistance for war supply contracts to

China. Australia also prevented a Japanese government-owned company from taking

over an iron mine in Australia, and banned iron ore exports in 1938. However,

in July 1939, negotiations between Japanese Foreign Minister Arita Khatira and

the British Ambassador in Tokyo, Robert Craigie, led to an agreement by which

the United Kingdom recognized Japanese conquests in China. At the same time,

the US government extended a trade agreement with Japan for six months, then

fully restored it. Under the agreement, Japan purchased trucks for the Kwantung

Army, machine tools for aircraft factories, strategic materials (steel and

scrap iron up to 16 October 1940, petrol and petroleum products up to 26 June

1941), and various other much-needed supplies.

In

a hearing before the United States Congress House of Representatives Committee

on Foreign Affairs on Wednesday, 19 April 1939, the acting chairman Sol Bloom

and other Congressmen interviewed Maxwell S. Stewart, a former Foreign Policy

Association research staff and economist who charged that America's Neutrality

Act and its "neutrality policy" was a massive farce which only

benefited Japan and that Japan did not have the capability nor could ever have

invaded China without the massive amount of raw material America exported to

Japan. America exported far more raw material to Japan than to China in the

years 1937–1940. According to the United States Congress, the U.S.'s third

largest export destination was Japan until 1940 when France overtook it due to

France being at war too. Japan's military machine acquired war materials, automotive

equipment, steel, scrap iron, copper, oil, that it wanted from the United

States in 1937–1940 and was allowed to purchase aerial bombs, aircraft

equipment, and aircraft from America up to the summer of 1938. A 1934 U.S.

State Department memo even noted how Japan's business dealings with Standard

Oil of New Jersey company, under the leadership of Walter Teagle, made United

States oil the "major portion of the petroleum and petroleum products now

imported into Japan." War essentials exports from the United States to

Japan increased by 124% along with a general increase of 41% of all American

exports from 1936 to 1937 when Japan invaded China. Japan's war economy was

fueled by exports to the United States at over twice the rate immediately

preceding the war. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, Japan

corresponded to the following share of American exports.

Japan

invaded and occupied the northern part of French Indochina in September 1940 to

prevent China from receiving the 10,000 tons of materials delivered monthly by

the Allies via the Haiphong–Yunnan Fou Railway line.

On

22 June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union. In spite of non-aggression

pacts or trade connections, Hitler's assault threw the world into a frenzy of

re-aligning political outlooks and strategic prospects.

On

21 July, Japan occupied the southern part of French Indochina (southern Vietnam

and Cambodia), contravening a 1940 gentlemen's agreement not to move into

southern French Indochina. From bases in Cambodia and southern Vietnam,

Japanese planes could attack Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies. As

the Japanese occupation of northern French Indochina in 1940 had already cut

off supplies from the West to China, the move into southern French Indochina

was viewed as a direct threat to British and Dutch colonies. Many principal

figures in the Japanese government and military (particularly the navy) were

against the move, as they foresaw that it would invite retaliation from the

West.

On

24 July 1941, Roosevelt requested Japan withdraw all its forces from Indochina.

Two days later the US and the UK began an oil embargo; two days after that the

Netherlands joined them. This was a decisive moment in the Second Sino-Japanese

War. The loss of oil imports made it impossible for Japan to continue

operations in China on a long-term basis. It set the stage for Japan to launch

a series of military attacks against the Allies, including the attack on Pearl

Harbor on 7 December 1941.

In

mid-1941, the United States government financed the creation of the American

Volunteer Groups (AVG), of which one the "Flying Tigers" reached

China, to replace the withdrawn Soviet volunteers and aircraft. The Flying

Tigers did not enter actual combat until after the United States had declared

war on Japan. Led by Chennault, their early combat success of 300 kills against

a loss of 12 of their newly introduced Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters heavily

armed with six 0.50-inch caliber machine guns and very fast diving speeds

earned them wide recognition at a time when the Chinese Air Force and Allies in

the Pacific and SE Asia were suffering heavy losses, and soon afterwards their

"boom and zoom" high-speed hit-and-run air combat tactics would be

adopted by the United States Army Air Forces.

Disagreements

existed both between the United States and the Nationalists, and within the

United States military, about the form of aid. Chennault contended that aid

should be in the form of building on the success of the Flying Tigers and go to

the US Fourteenth Air Force in China. Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell, who

was in charge of training Nationalist divisions equipped by the United States,

became increasingly frustrated by the Nationalists' refusal to use them to

fight the Japanese in Burma or in southeastern China.

The

Sino-American Cooperative Organization was an organization created by the SACO

Treaty signed by the Republic of China and the United States of America in 1942

that established a mutual intelligence gathering entity in China between the respective

nations against Japan. It operated in China jointly along with the Office of

Strategic Services (OSS), America's first intelligence agency and forerunner of

the CIA while also serving as joint training program between the two nations.

Among all the wartime missions that Americans set up in China, SACO was the

only one that adopted a policy of "total immersion" with the Chinese.

The "Rice Paddy Navy" or "What-the-Hell Gang" operated in

the China-Burma-India theater, advising and training, forecasting weather and

scouting landing areas for USN fleet and Gen Claire Chennault's 14th AF,

rescuing downed American flyers, and intercepting Japanese radio traffic. An

underlying mission objective during the last year of war was the development

and preparation of the China coast for Allied penetration and occupation. Fujian

was scouted as a potential staging area and springboard for the future military

landing of the Allies of World War II in Japan.

United Kingdom

After

the Tanggu Truce of 1933, Chiang Kai-Shek and the British government would have

more friendly relations but were uneasy due to British foreign concessions

there. During the Second Sino-Japanese War the British government would

initially have an impartial viewpoint toward the conflict urging both to reach

an agreement and prevent war. British public opinion would swing in favor of

the Chinese after Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen's car which had Union Jacks on it

was attacked by Japanese aircraft with Hugessen being temporarily paralyzed

with outrage against the attack from the public and government. The British

public were largely supportive of the Chinese and many relief efforts were untaken

to help China. Britain at this time was beginning the process of rearmament and

the sale of military surplus was banned but there was never an embargo on

private companies shipping arms. A number of unassembled Gloster Gladiator

fighters were imported to China via Hong Kong for the Chinese Air Force.

Between July 1937 and November 1938 on average 60,000 tons of munitions were

shipped from Britain to China via Hong Kong. Attempts by the United Kingdom and

the United States to do a joint intervention were unsuccessful as both

countries had rocky relations in the interwar era.

In

February 1941 a Sino-British agreement was forged whereby British troops would

assist the Chinese "Surprise Troops" units of guerrillas already

operating in China, and China would assist Britain in Burma.

When

Hong Kong was overrun in December 1941, the British Army Aid Group (B.A.A.G.)

was set up and headquartered in Guilin, Guangxi. Its aim was to assist

prisoners of war and internees to escape from Japanese camps. This led to the

formation of the Hong Kong Volunteer Company which later fought in Burma.

B.A.A.G. also sent agents to gather intelligence – military, political and

economic in Southern China, as well as giving medical and humanitarian

assistance to Chinese civilians and military personnel.

A

British-Australian commando operation, Mission 204 (Tulip Force), was

initialized to provide training to Chinese guerrilla troops. The mission

conducted two operations, mostly in the provinces of Yunnan and Jiangxi.

The

first operation commenced in February 1942 from Burma on a long journey to the

Chinese front. Due to issues with supporting the Chinese and gradual disease

and supply issues, the first phase achieved very little and the unit was withdrawn

in September.

Another

phase was set up with lessons learned from the first. Commencing in February

1943 this time valid assistance was given to the Chinese 'Surprise Troops' in

various actions against the Japanese. These involved ambushes, attacks on

airfields, blockhouses, and supply depots. The unit operated successfully

before withdrawal in November 1944.

Commandos

and members of SOE who had formed Force 136, worked with the Free Thai Movement

who also operated in China, mostly while on their way into Thailand.

After

the Japanese blocked the Burma Road in April 1942, and before the Ledo Road was

finished in early 1945, the majority of US and British supplies to the Chinese

had to be delivered via airlift over the eastern end of the Himalayas known as

"The Hump". Flying over the Himalayas was extremely dangerous, but

the airlift continued daily to August 1945, at great cost in men and aircraft.

French

Indochina

The

Chinese Kuomintang also supported the Vietnamese Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDD)

in its battle against French and Japanese imperialism. In Guangxi, Chinese

military leaders were organizing Vietnamese nationalists against the Japanese.

The VNQDD had been active in Guangxi and some of their members had joined the

KMT army. Under the umbrella of KMT activities, a broad alliance of

nationalists emerged. With Ho at the forefront, the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh

Hoi (Vietnamese Independence League, usually known as the Viet Minh) was formed

and based in the town of Jingxi. The pro-VNQDD nationalist Ho Ngoc Lam, a KMT

army officer and former disciple of Phan Bội Châu, was named as the deputy of

Phạm Văn Đồng, later to be Ho's Prime Minister. The front was later broadened

and renamed the Viet Nam Giai Phong Dong Minh (Vietnam Liberation League).

The

Viet Nam Revolutionary League was a union of various Vietnamese nationalist

groups, run by the pro Chinese VNQDD. Chinese KMT General Zhang Fakui created

the league to further Chinese influence in Indochina, against the French and

Japanese. Its stated goal was for unity with China under the Three Principles

of the People, created by KMT founder Dr. Sun and opposition to Japanese and

French Imperialists. The Revolutionary League was controlled by Nguyen Hai

Than, who was born in China and could not speak Vietnamese. General Zhang

shrewdly blocked the Communists of Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh from entering the

league, as Zhang's main goal was Chinese influence in Indochina. The KMT

utilized these Vietnamese nationalists during World War II against Japanese

forces. Franklin D. Roosevelt, through General Stilwell, privately made it

clear that they preferred that the French not reacquire French Indochina

(modern day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) after the war was over. Roosevelt

offered Chiang Kai-shek control of all of Indochina. It was said that Chiang

Kai-shek replied: "Under no circumstances!"

After

the war, 200,000 Chinese troops under General Lu Han were sent by Chiang

Kai-shek to northern Indochina (north of the 16th parallel) to accept the

surrender of Japanese occupying forces there, and remained in Indochina until

1946, when the French returned. The Chinese used the VNQDD, the Vietnamese

branch of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in French

Indochina and to put pressure on their opponents. Chiang Kai-shek threatened

the French with war in response to maneuvering by the French and Ho Chi Minh's

forces against each other, forcing them to come to a peace agreement. In

February 1946, he also forced the French to surrender all of their concessions

in China and to renounce their extraterritorial privileges in exchange for the

Chinese withdrawing from northern Indochina and allowing French troops to

reoccupy the region. Following France's agreement to these demands, the

withdrawal of Chinese troops began in March 1946.

Central

Asian Rebellions

In

1937, then pro-Soviet General Sheng Shicai invaded Dunganistan accompanied by

Soviet troops to defeat General Ma Hushan of the KMT 36th Division. General Ma

expected help from Nanjing, but did not receive it. The Nationalist government

was forced to deny these maneuvers as "Japanese propaganda", as it

needed continued military supplies from the Soviets.

As

the war went on, Nationalist General Ma Buqing was in virtual control of the Gansu

corridor. Ma had earlier fought against the Japanese, but because the Soviet

threat was great, Chiang in July 1942 directed him to move 30,000 of his troops

to the Tsaidam marsh in the Qaidam Basin of Qinghai. Chiang further named Ma as

Reclamation Commissioner, to threaten Sheng's southern flank in Xinjiang, which

bordered Tsaidam.

The

Ili Rebellion broke out in Xinjiang when the Kuomintang Hui Officer Liu Bin-Di

was killed while fighting Turkic Uyghur rebels in November 1944. The Soviet

Union supported the Turkic rebels against the Kuomintang, and Kuomintang forces

fought back.

Ethnic

Minorities

Japan

attempted to reach out to Chinese ethnic minorities in order to rally them to

their side against the Han Chinese, but only succeeded with certain Manchu,

Mongol, Uyghur, and Tibetan elements.

The