The attack on the military forces of the U.S. at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, did not just happen nor was it a quick reaction to initiatives instituted by President Roosevelt. The Japanese believed that they were being pushed into a corner by Roosevelt and felt that they must act to protect the Empire. Gordon Prange in At Dawn We Slept describes pre-attack events in detail. The description of these events note the mistakes made on each side.

1937

July: The Japanese Army invaded north China from Manchuria, eight years of combat with the Chinese began.

December: The gunboat U.S.S. Panay, while on routine duty in Chinese waters, was attacked by Japanese aircraft. We do not know if the attack was intentional or an accident but Roosevelt looked for ways to punish Japan. Nothing became of this incident because the Japanese government apologized, paid for all damages, and promised to protect American nationals.

1938

October: With the continued German military rearmament program and European leadership capitulation at the Munich conference, President Roosevelt asked Congress for $500 million to increase America’s defense forces. This action was done because he believed that Germany was a threat to the U.S. The Japanese saw this build up as a direct threat to their Empire because the U.S. was the only country in the Pacific which could impede their expansion.

1939

February: Japan continues its conquest of China by occupying Hainan Island off the southern coast. This occupation improved Japan’s ability to interdict maritime trade routes.

Because the U.S. was the primary military threat in the Pacific, Japan had prepared war plans to deal with this problem, and the U.S. had similar war plans aimed at Japan. The Japanese plan was to conduct one large naval battle against the American Navy, destroying it, resulting in the inability of the U.S. to interfere with Japanese expansion throughout Asia. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto assumed command of Japan’s Combined Fleet in August of 1939. Having lived in America for several years, he knew Americans, the type of people we were, and he knew that this war plan was impractical. He needed a new plan which would remove the threat of U.S. intervention from his flank.

1940

January: Sometime between January and March 1940 Yamamoto devised his plan to destroy the U.S. Navy in Hawaii and demoralize the American people. Prange asks the question “Why did Yamamoto think that this attack would crush American morale since he knew them?” but he does not answer his own question. No actions were implemented to put the plan in action.

July: Trade sanctions followed by a trade embargo were imposed resulting in increased ill-will and additional political problems with Japan. These trade actions were imposed because Roosevelt was attempting to stop Japanese expansion.

1941

January: Admiral Yamamoto begins communicating with other Japanese officers, asking them if an attack on Pearl Harbor would be possible. The final outcome of these discussions was the attack was possible but would be difficult.

Secrecy and surprise were the two elements which were most important to the success of this plan. With that said one wonders how secure was the flow of information around the Imperial Naval Staff, because on 27 January 1941, Joseph C. Gerow, the U.S. Ambassador to Japan, wired Washington that he had learned information that Japan, in the event of trouble with the U.S., was planning a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

No one in Washington believed the information. If someone had believed this information, the Pearl Harbor attack possibly could have been avoided. While many thought that war was possible, no one believed that the Japanese could surprise us.

Most senior American military experts believed that the Japanese would attack Manila in the Philippine Islands. Manila’s location threatened the sea lanes of communications as the Japanese military forces moved south. Another thought to location of attack was toward the north into Russia because of the war in Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union.

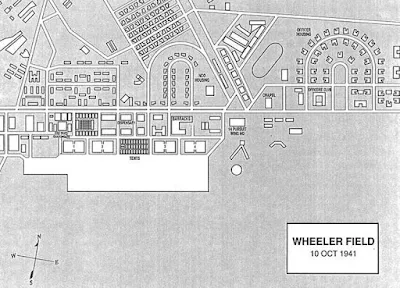

February: As the Japanese were conducting preliminary planning for the attack, Americans were preparing to defend American property. Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, Commanding General of the Hawaiian Department, prepared Hawaii for attack. Defense of the islands was an Army responsibility though the Navy did play a major role in preparing to repel an attack.

Admiral Kimmel planned on taking his fleet out of the harbor and confronting the enemy at sea.

With this in mind both officers communicated with their seniors in Washington attempting to obtain additional men and equipment to insure a proper defense of all military installations on Oahu. At this time, war production of the U.S. was still limited resulting with the dispersal of material around the world trying to fill everyone’s needs: Britain, Russia, the Philippines and Hawaii.

March: Nagao Kita, Honolulu’s new Consul General arrives on Oahu with Takeo Yoshikawa, a trained spy. As the military of both countries prepared for possible war, the planners needed information about the opponent.

The U.S. knew that Hawaii was full of Japanese intelligence officers but because of our constitutional rights very little could be done. Untrained agents like Kohichi Seki, the Honolulu consulate’s treasurer, traveled around the island noting all types of information about the movement of the fleet. When the attack occurred the Japanese had a very clear picture of Pearl Harbor and where individual ships were moored.

April: During the time period U.S. intelligence officers continued to monitor Japanese secret messages.

American scientists had developed a machine, code named “Magic” which gave U.S. intelligence officers the ability to read Japanese secret message traffic. “Magic” provided all types of high quality information but because of preconceived ideas in Washington some data was not followed up on and important pieces of the pre-attack puzzle were missed.

Japanese consular traffic was also intercepted which provided additional intelligence. While the U.S. had all the data needed to arrive at a clear picture of Japanese intentions, the Navy had an internal struggle between the Office of Naval Intelligence and the War Plans Division about which department should be the primary collection office. When the War Plans Division was finally designated the first in line for data, all of the Navy’s intelligence collection was degraded.

To further complicate this problem the Army had its own intelligence office, G-2. At times the Army and the Navy did not talk to each other, again reducing the ability to divine Japan’s intentions. Finally, Washington did not communicate all the available information that was received to all commands, at times thinking that such a transmission would result in duplication. All in all, the U.S. knew that Japan was going to expand its war but the question remained, where? If U.S. intelligence people had communicated, preparations for the attack could have been improved.

May: Admiral Nomura informed his superiors that he had learned Americans were reading his message traffic. No one in Tokyo believed that their code could have been broken. The code was not changed.

If the Japanese had changed their code, the surprise of the attack would have occurred as it did but would we have been as poorly prepared or could the result have been even worse? This mistake would have impacted follow-on actions through 1942.

July: Throughout the summer Yamamoto trained his forces. His staff and the Naval General Staff finalized the planning of the attack: what route to travel on, how much fuel would be required for the trip, what U.S. ships would be in the harbor and where they would be moored.

The Japanese planners also had to coordinate their own requirement of additional military action around Indochina. Which action was more important and which would provide the greatest gain had to be worked out.

November: Tokyo sends Saburo Kurusu, an experienced diplomat to Washington as a special envoy to assist Ambassador Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, who continued to seek a diplomatic solution.

Japan wanted the U.S. to agree to its southern expansion diplomatically but if they were unsuccessful, they would go to war.

On the 16th the first units, submarines involved in the attack, departed Japan.

On the 26th the main body, aircraft carriers and escorts, began the transit to Hawaii.

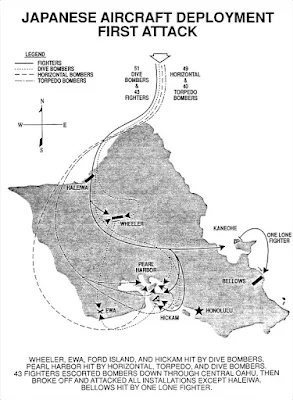

December 7th: At 0750, Hawaiian time, the first wave of Japanese aircraft began the attack. Along with the ships in Pearl Harbor, the air stations at Hickam, Wheeler, Ford Island, Kaneohe and Ewa Field were attacked.

For two hours and twenty minutes, Japanese aircraft bombed and shot up these military targets. When the second wave returned to their carriers, 2,403 people had been killed and 1,178 were wounded. Eighteen ships of different sizes had been sunk or damaged and seventy-seven aircraft of all types had been destroyed.

Only twenty-nine Japanese aircraft were shot down by American return fire, most during the attack of the second wave. This number of planes downed is significant but had the defenses of Hawaii been prepared the number would have been greater.

|

| December 7, 1941 Oahu map showing the Japanese flights paths and ship arrangements around Ford Island. |

|

| Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941 with a few present-day facilities. |

No comments:

Post a Comment