|

| Signal photographic companies included technicians for the maintenance and repair of cameras. |

|

| Camera equipment laid out for inspection. |

|

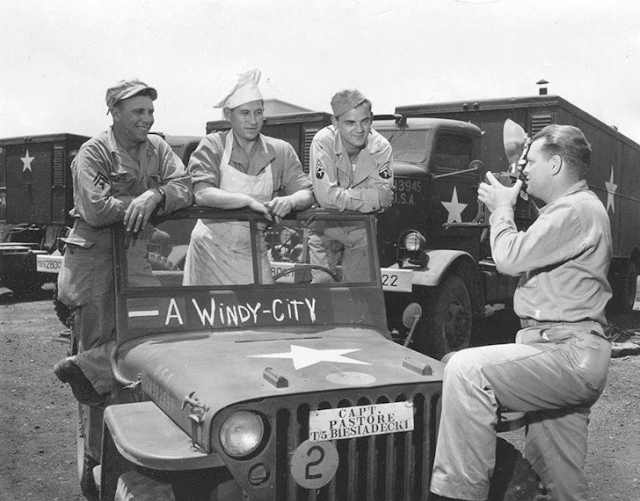

| Cameras were used to photograph everything from the home front to combat. Here a cameraman takes the picture of some service troops in North Africa. |

|

| Combat camera teams of the 163rd Signal Photographic Company stand for inspection with their still and motion picture cameras set up. |

|

| Signal Corps photographer Sgt. George O. Miehle takes a photo of Sgt. Carl T. Delbridge of the 66th Division in his foxhole. |

|

| Navy photographer William Barr snapped this dramatic moment as a kamikaze exploded on the flight deck of the USS Enterprise, May 14, 1945. |

|

| Barr also took this shot after a TBM Avenger missed the arresting wire during landing and crashed into parked planes onboard the Enterprise, April 11, 1945. |

|

| Corporal Hugh McHugh, shown with his 4×5 Speed Graphic PH-104, was killed by a sniper January 15, 1945 in Belgium. |

|

| A German newsreel cameraman focuses on an armored column moving into the Soviet Union. Like their American and British counterparts, German cameramen superbly documented the war. |

|

| Emil Edgren shot this image of an American GI with a Browning Automatic Rifle looking at a B-17 that crash-landed in a Belgian field. |

|

| A helmetless American paratrooper from the 82nd Airborne Division carrying a tommygun in full gallop across a Belgian field was captured by the lens of Emil Edgren. |

|

| A dead German soldier photographed by Emil Edgren. |

|

| This photo of General Douglas MacArthur at the microphone was taken by Charles Restifo during the Japanese surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri. |

|

| Charles Restifo behind his 4×5 PH-104 camera. Although big and bulky, the PH-104 used large-format sheet film that resulted in crisp, detailed photos. |

|

| Charles Restifo’s photograph of the desolation at Hiroshima. He was one of the first photographers allowed into the destroyed, radioactive city. |

|

| William Wilson’s color photograph of a temporary U.S. war cemetery on the northern coast of Sicily, 1944. |

No comments:

Post a Comment