|

| First tank in Bastogne, "Cobra King," M4A3E2 Jumbo. |

by A. Harding Ganz

Bigonville was rough.

With intelligence of advancing German armor, Reserve Command (CCR) had been

committed on the right flank, as the other two combat commands of the American

4th Armored Division continued to slug north toward Bastogne and the

beleaguered paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division. Colonel Wendell

Blanchard, commander of CCR, had the 37th Tank, 53rd Armored Infantry and 94th

Armored Field Artillery Battalions, when the command jumped off on 23 December

1944. The Reconnaissance Platoon of the 37th Tank preceded the advance

guard—Team B (B Company, 37th Tank, and B Company, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalions)—as

far as the 25th Cavalry's outpost, where Lieutenant Marion Harris pulled the

platoon aside and waved the column on.

The approach march to

contact, along the sheer, ice-covered secondary road was difficult, and tanks

and half-tracks skidded out of control. Initially, Team B received no fire, nor

observed any enemy, save an enormous pair of very large enemy tank tracks

looming before it in the new-fallen snow.

But as the team

approached Flatzbourhof—the Bigonville-Holts railroad station—it began to

receive tank, anti-tank and machine gun fire from the railroad building and

adjacent woods. Captain Jimmie Leach, commander of B Company, 37th Tank

Battalion and of Team B, deployed his force along the railroad embankment,

while the artillery pounded the nearby woods and German positions beyond the

railroad station.

As expected, the

Germans were quick to counterattack, with white-clad paratroopers, reinforced

by two self-propelled guns and a captured M4 Sherman tank. Just as quickly, B

Company, 37th Tank Battalion tanks, firing from their positions behind the

railroad embankment, dispatched all three German vehicles, halting the

counterattack. During the fight, it was Sherman against Sherman, with Captain

Leach's gunner coming out a winner.

As darkness fell Team B

was ordered to hold its position, while Lieutenant Colonel Creighton W.

Abrams Jr., commanding the 37th Tank Battalion, attempted to maintain the

momentum of his attack by sending the tanks of A Company through Team B, and

those of C Company around its right flank. However, stubborn resistance by

tank-reinforced troopers of the German 13th Parachute Regiment, mines and

casualties, brought the attack to a standstill a full mile away from

Bigonville, the CCR objective. A Company, 37th Tank Battalion's passage of B

Company, 37th Tank Battalion's lines was aborted due to numerous vehicles lost

to snow-covered mines, including Lieutenant John Whitehill's command tank; and

C Company, 37th Tank Battalion's attack was likewise aborted because of the

loss of nine tank commanders, including the commanding officer, Captain Charlie

Trover, who was killed.

During the cold, clear

night with outposts alert, the CCR tankers, redlegs (artillerymen) and doughs

(infantrymen) received some badly needed replacements. They repaired their

vehicles and reorganized their troops and crews for the next morning's attack.

On the 24th, Team B's

tanks and doughs attacked again, fighting their way into the very center of

Bigonville, where the tough troopers of the German 5th Parachute Division had

to be blasted out house by house. Small arms and panzerfaust fire continued

to take its toll. Lieutenant Bob Cook, B Company, 37th Tank Battalion's

executive officer and 3rd Platoon leader, went down with a rifle bullet in his

chest. He was briefly captured by the Germans while he was attempting to find

the accompanying medic jeep, but abandoned as the B Company doughs advanced.

As the Bigonville

battle continued, Colonel Abrams ordered a blocking and screening position,

without its infantry, to the north of town. No sooner had its tanks moved into

position, than a flight of four American P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers,

thinking them enemy, made two bombing and strafing attacks on them. Captain

Leach and his tank crews tossed out red smoke grenades, and frantically

attempted to uncover the red recognition panels for identification, while the

battalion S-3, Captain Bill Dwight, radioed Colonel Abrams to call off the "friendlies."

There were no casualties—luckily the U.S. fliers had missed everyone and

everything.

When the mopping up was

over, Bigonville and the surrounding area yielded some 400 prisoners of war

and 100 enemy dead to the tenacious CCR attackers.

With Bigonville

secured, CCR looked forward to spending a restful Christmas Day, feasting on a

turkey dinner. The battalions were much under strength, and the 37th Tank

Battalion in particular, had just completed a 160-mile road march up from

Lorraine and the Saarland, where it had been supporting the newly-arrived 87th "Golden

Acorn" Infantry Division in the Westwall fighting.

When alerted for the "fire

call" run to the Ardennes, the 4th Armored Division had just been pulled

out of line in Lorraine after a month of slugging from the Seille valley to the

German border. Mud and mines had restricted the tanks, overcast had grounded

the tactical air support, and the revitalized German defense had skillfully

parried every thrust—all of which combined to deny Patton a breakthrough.

Having achieved a brilliant reputation as it slashed across France after the

Normandy breakout, the 4th Armored was bitter about the casualties it had

suffered in the November offensive. Knocked-out tanks were strewn along the

way in what was considered an atrocious misuse of armor; and after a shouting

match with his corps commander, Major General John S. Wood, the 4th Armored's

beloved commanding general, was relieved by Lieutenant Gen. George S. Patton

Jr., 3rd Army commander.

But Patton gave the 4th

his own chief of staff, Major General Hugh Gaffey, who had commanded the 2nd

Armored in Sicily. "Gimlet-eyed Gaffey," the laconic Texan with

immaculate riding breeches and "boots you could use as a mirror," had

a style completely unlike the bluff, good-natured "P" Wood. But he

was coolly efficient, and the 4th was an experienced war machine.

On 22 December 1944,

the 4th Armored, under Milikin's new III Corps in Belgium, jumped off to drive

on Bastogne where the 101st "Screaming Eagles" Airborne Division was

surrounded by the German offensive of the Battle of the Bulge.

The counterattack cut

into the still-expanding torrent of the German offensive, and resistance

stiffened north of the Sure River. Patton, who had promised to reach Bastogne "by

Christmas," found his advance stalling. On the 24th, Milikin decided to

regroup his forces to concentrate more power for the relief of Bastogne. Two

battalions of the 80th "Blue Ridge" Infantry Division were trucked

over to reinforce the armor, and the boundary of the 26th "Yankee"

Division was extended to include the Bigonville area, thereby releasing CCR

to the 4th Armored Division.

By doctrine and

practice, CCR was not employed tactically. Its TO&E headquarters was much

smaller than those of Combat Commands A and B (CCA, CCB) and it was only

intended to administratively control units not in the line. But Gaffey

employed the reserve tactically, to meet the threat to the right flank at

Bigonville, and now he intended to shift it around to the left, to seek a weak

spot in the German front.

CCR had just turned in

on Christmas eve, when it received orders for a 27-mile night road march from

Bigonville around to Neufchateau highway leading to Bastogne. Attended by

appropriate griping, the column crossed the initial point (IP) an hour after

midnight under radio listening silence, with the reconnaissance platoon jeeps

and light tanks of the 37th Tank Battalion leading as the point.

Then came the advance

guard, comprising the light tank company (D Company, 37th Tank Battalion

[–]), B Company, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion mounted in half-tracks, and a

squad of C Company, 24th Armored Engineers to clear obstacles.

Five minutes back came

the main body of the combat command, with the rest of Lieutenant Colonel

Creighton W. (Abe) Abrams' 37th Tank Battalion and Lieutenant Colonel George

Jaques' 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion; the M7 105 mm Priest self-propelled

howitzers of Lieutenant Colonel Robert Parker's 94th Armored Field Artillery

with C Battery of 155 mm towed howitzers attached from the 177th Field Artillery;

two gun companies, of the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and other

attachments. Service and supply elements came separately, under CCR Trains

command.

The Christmas eve night

was clear and cold, lit by a nearly full moon, while flares and explosions

illuminated the northern horizon at Bastogne. As the column twisted through the

dark forest areas, bleary-eyed drivers tried to focus on the cat-eye blackout

markers of the vehicle ahead. In the open half-tracks, armored doughs dozed

fitfully and stomped their frozen feet to regain circulation. There were some

400 vehicles in the column that stretched over 16 miles of road space. Standing

operating procedures called for an eight-miles-per-hour rate-of-march at a

50-yard closed interval at night (15 miles per hour at a 100-yards open

interval by day), with a one minute interval between company march units and

five minutes between battalion march groups (serials), giving a time length of

about two hours. Thus, the vanguard of the column had already pulled into its

assembly area south of Vaux while the rest of the column was still closing on

the release point (RP) at Molinfaing.

As the troops topped

off their vehicles and got a cat-nap their commanders attended a conference

for planning the Christmas Day attack. If there were prayers, they were silent

and individual. CCR's mission was flank protection, with the main drive still

to be mounted by CCB, in the center. The three combat commands were deployed

abreast, each comprising a tank battalion, an armored infantry battalion, a

direct support armored field artillery battalion, and the normal attachments;

a company each from the tank destroyer, engineer, medical,

ordnance-maintenance and anti-aircraft artillery battalions, a troop from the

cavalry/reconnaissance squadron and the MP platoon, as well as supporting II

Corps artillery.

In Lorraine, each

combat command had operated with two battalion-sized task forces, the tank and

armored infantry battalions cross-reinforcing each other. But because of the constricted

terrain in the Ardennes, there was only one ridge-running road on the axis of

advance of each combat command: the Arlon-Martelange highway for CCA; a

secondary road through Chaumont for CCB, bounded by the Strainchamps and Burnon

creeks; and the Neufchateau highway for CCR—a zone of advance eight miles wide.

Thus, the tank and armored infantry companies were paired as teams to leap-frog

from village to village, with the infantry and tank battalion commanders

working closely together. Normal practice for the three company teams was to

leap-frog from assault to reserve, to support, with a team's turn to lead

coming up every third turn.

The 37th Tank Battalion

had three medium tank companies and one light tank company, supported by the M4

105 mm assault gun and 81 mm mortar platoons of Headquarters Company. Since

each of the 37th's three medium companies were down to nine of ten tanks

instead of seventeen, they often maneuvered as one unit (rather than in three

platoons), deploying from column into line, wedge, echelon, or line of sections

formation, depending on terrain. If serious resistance was expected, the

armored doughs left their thin-skinned half-tracks and "married up"

with the tanks in the attack position just short of the line of departure (LD),

mounting a squad on the rear deck of each tank. The platoon leaders mounted

their counterparts tanks to facilitate control by using the tank company

radio frequency. The tank company commanding officer commanded the team's

assault until the infantrymen dropped off and went into action on their own.

Each team advance would

be preceded by direct fire from the supporting team, a sharp artillery

concentration on call by the forward observer in his tank, and tactical air

support by P-47 fighter planes, if available. The few air controllers were

normally at combat command headquarters.

The commander of the

37th Tank Battalion was chunky, 29-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Creighton W.

(Abe) Abrams, who was already making a fighting name for himself. In 1944 campaigns,

Abrams' aggressive leadership of the 37th, under the skillful direction of

Colonel Bruce C. Clarke of CCA, did much to establish "P" Wood's 4th

Armored as Patton's favorite division. (When the German Ardennes offensive

began, Clarke had gone to CCB of the 7th Armored with a brigadier general's

star and was blunting the German drive in the St. Vith sector as the 4th fought

toward Bastogne.) Abe's combat philosophy was simple: "Our operations are

all based on violence," and "Go east, it's the quickest way home."

Abrams had developed

the 37th Tank as a finely-honed fighting unit. His staff not only functioned

well as such, but he often used his staff officers to direct his attacks. They

would monitor both battalion and company radio frequencies, leaving the

company commanders free to handle their units, yet the battalion commanding

officer was kept in close touch with the situation.

As the 105 mm assault

gun tank of each company was frequently grouped with the battalion assault gun platoon,

so too did Abe take the seventeenth tank from each of the medium companies and

give them to his S-2, S-3 and liaison officer (LNO). These headquarters tanks,

with those of the commanding officer and executive officer, received names

beginning with "T," just as the company tank name began with the

company letter. Thus, Abe rode in "Thunderbolt VI" (he would wear out

seven M4's during the war), with its name painted on its flanks in letters

eight inches high on a background of billowing white clouds punctured by

jagged red streaks of lightning. "We can always spot his tank," said

A Company, 37th Tank Battalion's Lt. John Whitehill, "because it doesn't

roll ahead like others. It gallops." And in the hatch was Abe, his long,

black unlighted cigar clenched in his teeth, aggressively jutting forward,

looking like "just another gun." He led by courageous example, and

the 37th's motto was "Courage Conquers."

The 53rd Armored

Infantry Battalion was still absorbing reinforcements from the Lorraine

fighting. The armored infantry had long since discarded their 57 mm anti-tank

guns as useless against German panzers, and the anti-tank platoon of each of

the three rifle companies was used as a fourth rifle platoon or as replacements.

Though badly under their TO&E strength of ten men (excluding the half-track

driver), the three rifle squads of each platoon augmented their firepower by

mounting an additional machine gun on their half-track, and by trading tanker

jackets for Browning automatic rifles (BAR) and Thompson submachine guns

(Tommy guns). The rifle platoon leaders each had a 60 mm mortar squad and a

light machine gun squad with two .30-caliber light machine guns to provide fire

support, backed up by the battalion assault gun, mortar and machine gun platoon.

The commander of the

53rd Armored Infantry Battalion was Lt. Col. George L. Jaques, "Jigger

Jakes," whom his fellow Bay Stater, Abrams, addressed over the radio as "Sadsack."

In fast-moving armored combat, nicknames were preferred to the daily changing

SOI call signs, and voice recognition as authentication. More orthodox than

the tanker, "going by the book," Jaques was ably seconded by his

battalion executive officer, Major Henry A. Crosby. The 53rd Armored Infantry

Battalion was an experienced outfit.

Both battalion

commanders had more tactical experience and expertise than their CCR commander,

and it was Abe who head the final drive to Bastogne.

At 1100 hours on

Christmas Day, the drive began. The German combat outpost line was quickly scattered

as CCR tanks roared down the highway, firing as they went. In fact, the only

obstacles encountered were those emplaced earlier by American engineers

withdrawing from the onslaught of the German offensive. The 37th's S-3, Captain

Bill Dwight, had hit a mine on the night road march in his tank "Tonto."

It was an American mine, "fortunately," and only broke a track block,

which was soon replaced. While returning to his command post the next day, Abe

hit another mine that tossed him out of his peep—unscratched—but totaled the

peep and crippled his driver. "Another lesson about marking minefields,"

wryly observed the 37th Tank Battalion's executive officer, Major Ed Bautz.

As Baker Company of the

53rd Armored Infantry Battalion cleaned out Vaux-les-Rosieres, the armored

spearhead continued up the highway toward Bastogne, ten miles ahead.

The German main line of

resistance was probably astride the highway itself, covering the primary armor

approach. But the available intelligence, such as it was, was not of much help.

Red-penciled enemy symbols cluttered the situation maps, many with question

marks. (It is now known that it was the 5th Parachute Division that had

responsibility for protecting the German southern flank, while the 26th

Volksgrenadier Division invested Bastogne, launching attacks in conjunction

with the 15th Panzergrenadier and Panzer Lehr Divisions.)

To avoid possible

minefields astride the highway, the armored attack swung off the hardtop beyond

Vaux into a secondary road that might be less defended. The terrain was fairly

open—snow-covered fields, patches of dark woods, and stone-built farm villages

dotted the countryside. D Company's light tanks and M18 Hellcat tank

destroyers outposted the flank beyond Petite Rosiers, while C Troop, 25th

Cavalry Squadron, screened the open flank to the west. Now, the main attack

began to pick up momentum. Team A tanks and infantry drove into Nives supported

by Team C, and then Team C passed through the town before it was cleared, on

its way to Cobreville. There radio contact with battalion was lost, but C Company,

37th Tank Battalion's commander, Lt. Charles Boggess, who had taken over the

tank company only two days before, acted on his own initiative and continued

the attack. While his team cleared the town, Boggess dismounted from his tank

around 1400 hours to reconnoiter an area where the road crossed a small creek,

and found the bridge had just been blown. Colonel Abrams called up his

tank-bulldozer, which crumpled a nearby stone wall and pushed it into the gap

so the drive would continue—it was moving again by 1530 hours.

Since the Cobreville

bridge had been prepared for demolition, it was likely that Remoiville would be

defended. Four artillery battalions pounded the town for ten minutes, while the

supporting Shermans blasted the stone buildings: "Gunner! Kraut

bazooka! Barn! HE! Traverse right! Steady … On! Eight hundred! Fire!"

Then Team A charged into the dust and rubble, with the tanks firing high

explosive rounds and spraying machine gun fire everywhere. B Company, 53rd

Armored Infantry Battalion, came in to help in the house-to-house fighting—it

was toss a grenade through a window, kick open the door, leap in and to the

side, and spray the room with Tommy gun fire. High-velocity tank shells

screamed through the upper floors, sending plaster dust flying. By 1800, 327

prisoners of war had been rounded up from the 3rd Battalion, 14th Parachute

Regiment.

The advance had already

rolled through Remoiville, but leading elements encountered a crater in the

road as dusk fell. B Company, 37th Tank Battalion, worked around to the left

and took up positions in and around Remoiville overlooking Remichampagne,

while infantry screened the woods to the west. CCR was now abreast of CCB,

which was in sight across the gorge of Burnon Creek, after having finally

driven the German paratroopers out of Chaumont. CCA had likewise slugged ahead

up the Arlon highway, but now the Germans were reinforcing their front to stop

the 4th Armored.

On Christmas night, the

infantry line companies dug in fronting on the Bois de Cohet and Remichampagne,

six miles from Bastogne. The 94th Armored Field Artillery had displaced by

battery up from Juseret to just south of Sure, from where its 105 mm

self-propelled howitzers could range to 12,000 yards, or almost to the outpost

lines of the 101st Airborne Division.

During the evening, a

German counterattack came down the highway from Sibret, but was warded off by

tank destroyer and artillery barrages.

The 37th Tank Battalion

and 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion command posts moved into Cobreville, and

the command post of CCR relocated to Vaux. The command posts were set up in

towns now, with the stone buildings providing both warmth and protection from

shell fragments, and the radios from the headquarters tracks were remoted

inside.

Colonel Blanchard came

forward to meet with Abrams, Jaques and Crosby. CCB was still slated to flank

onto the Arlon highway and enter Bastogne. Accompanying CCB was a fretting

Major General Maxwell Taylor, who had been on leave in the States when his

101st Airborne entrucked for the Ardennes. Now, he was impatient to rejoin his

command.

CCR was to cover the

left flank, advancing through Remichampagne and Clochimont, then turning left

toward Sibret, which was held in strength. The battalion commanders were

vehemently opposed to attacking Sibret. Instead they urged a drive directly to

Bastogne. Blanchard was concerned about the left flank thus being exposed, but

finally gave in at about 0300 hours stating, recalls Major Crosby, "that

if we failed it was on our heads and not his as he was refusing to take any

responsibility." The battalion commanders then issued oral attack orders

to their company commanders—armored units didn't take time to draw up

five-paragraph field orders.

As dawn broke on 26

December, CCR moved over frozen ground with Team B under Captain Jimmie Leach,

in "Blockbuster III," in the lead. Teams A and C laid down a base of

fire into the Bois de Cohet and Remichampagne. Lieutenant Don Guild, in his

forward observer (FO) tank, prepared to lift fires as the attack went in.

Suddenly P-47 fighters, probably from the 362nd Fighter Group, appeared

overhead. They had not been called in, and there was no forward air controller

to coordinate their actions, but they flew in, bombing and strafing only a few

hundred yards ahead of the tanks, and sent the Germans diving for cover.

Nonetheless, house-to-house fighting gave Team B a two-hour fight before the

town was secured at 1055.

Meanwhile, the armored

column passed through Remichampagne and, finding the Burnon Creek bridge

intact, continued on up the road to the crossroads to Clochimont. There,

Lieutenant Guild dismounted from his FO's tank, and personally captured about a

dozen Germans who were cowering in their slit trenches from the fierce assault.

Moments after joining

Leach at the crossroads and reviewing the situation, Colonel Abrams ordered A

Company, 37th Tank Battalion, to seize the high ground to the left of Clochimont.

But as A Company, 37th Tank Battalion, arrive don position, its tanks received

several rounds of anti-tank fire from a position down the road to the right of

Abrams in "Thunderbolt." "Gunner! Steady...On! Twelve hundred!

Fire!" Once again Abrams proved he had the best tank crew in the 37th. "Target!

Cease fire!"

By now, the 37th Tank

Battalion was down to 20 of its 53 TO&E medium tanks, and the 53rd Armored

Infantry Battalion was short 230 riflemen. While Abrams and Jaques were

coordinating their planning, hundreds of C-47 transport planes thundered low

over them, heading for Bastogne like flocks of fat geese. Red, yellow and blue

parachutes with supplies began blossoming out over the town. But so did ugly

bursts of German flak, and several planes arched down streaming flames. Since

Leach's Team B had gotten this far rather easily, Abrams was ready to drive for

Bastogne, and radioed the division commander directly. The other two combat commands

had made less than a mile each on the 26th. At 1400, Gaffey telephoned Patton

who quickly gave his approval for Abrams to move on Bastogne.

CCR artillery prepared

to fire on Assenois. A and C Batteries, which had displaced forward to Nives,

would fire on the woods north of town, B Battery on the south edge of the town,

and the 155's of C Battery, 177th Field Artillery, on the center. Additionally,

the three artillery battalions with a neighboring CCB were also tied in, to

give a total of 13 batteries to annihilate any enemy force in Assenois. D and A

Companies, 37th Tank Battalion, were to overwatch the Sibret road on the left

flank and give warning of any German tank movement.

Abrams then called his

S-3, Captain Bill Dwight, to bring up Team C from reserve. Lieutenant Boggess

mounted the battalion commander's tank for a briefing at the Clochimont

crossroads. There had been no reconnaissance up the road, but the area was

known to be strongly defended. Abe told him simply, "Get to those men in

Bastogne." The Charlie Company commander called his eight tank commanders

together and told them he would lead and set the speed of the attack. "You

all know we've got to get to those men in the town. All you've got to do is

keep 'em rollin' and follow me. It won't be any picnic, but we'll make it."

At 1620 hours, Abe gave

the familiar hand signal, "Let 'er roll," and the tanks moved out.

Boggess picked up speed, tracks squealing, and charged right through Clochimont

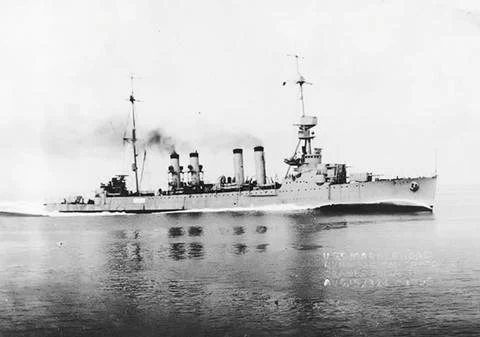

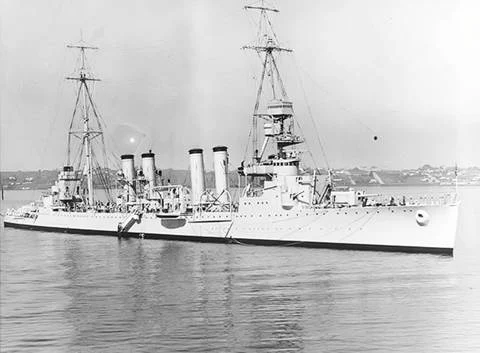

toward Assenois, guns firing. Three miles to go. Boggess in C-8, "Cobra

King," fired straight ahead, Lieutenant Walter Wrolson in the second tank

fired to the right, the third tank to the left. The Shermans pumped fire in all

directions, firing on the move, with their gyrostabilizers enabling them to

maintain the momentum of the attack. "I used the 75 like a machine gun,"

said "Cobra King's" gunner, Corporal Milton Dickerman. Boggess had

instructed him to choose his own targets. "Murphy was plenty busy throwing

in the shells. We shot twenty-one rounds in a few minutes and I don't know how

much machine gun stuff."

As soon as he had

cleared Clochimont Boggess called Abe for artillery fire on Assenois. Abrams

radioed, "Concentration Number Nine, play it soft and sweet." Almost

immediately the town seemed to erupt in a chaos of explosions. At the edge of

the town, Boggess called for the artillery to lift 200 yards, and barreled on

in without pausing. But there was German fire, even if erratic; Lieutenant

Chamberlain's FO peep was hit and he went into a ditch, and it was Lt. Billy

Wood in a Cub plane overhead who finally got the fire lifted.

Leaning into friendly

artillery fire cut losses from enemy resistance, but Assenois was a murky haze

of shell bursts and the dust of collapsing houses. Tank commanders in combat

usually road with head and shoulders out of the hatch because visibility

through the periscope was too limited; but Boggess had to pull his hatch down

to three or four inches above the turret roof because shell splinters were

singing off the armor. Dirt from an earlier enemy shell burst had smeared the

driver's periscope, and Hubert Smith "sorta guessed at the road." In

addition, the left brake locked and the "Cobra King" swerved up a

side street. Two other tanks also took wrong turns.

Walt Green's C Company

infantrymen had been following in their half-tracks but artillery fire was

still coming in and they piled out of their open-topped, thin-skinned vehicles

to seek any shelter they could find in the town. Simultaneously, the

defenders emerged from the cellars, and the armored doughs mixed it up with the

German paratroopers and Volksgrenadiers well into the night.

Nineteen-year-old

Private Jimmy Hendrix went swinging into two 88 mm gun crews with his M1

rifle, forcing them to surrender. He then silenced two machine guns and dragged

a dying GI from a burning half-track, all of which earned him the Congressional

Medal of Honor. Abrams followed into the confusion that was Assenois, and

even dismounted his tank to help wrestle a fallen telephone pole off a tank to

keep the attack moving.

Boggess cleared

Assenois with three tanks as dusk fell. A gap in the column had opened that

gave the Germans a chance to throw some Teller mines onto the roadway from a

dark treeline, and blow up a following half-track. Dwight was right behind in

his Sherman, "Tonto," and helped clear the wreckage and toss the

mines aside. The column moved forward again, running a gauntlet of

panzerfausts, mines and small arms fire. Four more half-tracks were lost. Dwight

was simultaneously trying to raise Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe and the

101st Airborne—"Tony, this is one of Hugh's boys, over"—on channel

20 assigned the command, but to no avail.

Up ahead "Cobra

King" lead the spearhead. Dickerman slammed three main gun rounds into an

old camouflaged concrete pillbox, and the bow gunner, Harold Hafner,

traversed his machine gun through a chow line of appalled German soldiers

standing under the snow-covered fir trees, knocking them over like bowling

pins. Suddenly the tanks debouched from the woods into an open field where

multi-colored supply parachutes dotted the snow. Boggess slowed as he

approached a line of foxholes, and called "Come on out, this is the Fourth

Armored." No answer from the wary GI's. Finally a khaki-clad figure

emerged to shake his hand. "I'm Lieutenant Webster of the 326th

Engineers, 101st Airborne Division. Glad to see you." At 1645 hours, CCR

logged in its journal: "Hole opened to surrounded forces at Bastogne …"

"Tonto" was

the fourth tank to arrive, followed by more half-tracks and other tanks, as

paratroopers gathered around, beginning to realize the siege was finally over.

Noting the clean-shaven faces Dwight muttered, "Well, things don't look so

Goddam rough around here to me." The airborne felt that discipline and

morale were closely related. One of the paratroopers asked the veteran tank

battalion S-3 if all tanks were commanded by officers, rather like the Air

Corps, as there were three officers in the first four tanks. Dwight said no.

But it was a significant observation; leadership in the 4th Armored was up

front. Dwight then met McAuliffe who had come up to the perimeter. To his

salute, the general replied, "Gee, I am mighty glad to see you."

Abrams joined them shortly thereafter.

Back at Assenois, B

Company, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, under Lt. Robert "Potsi"

Everson was committed to help clean out the town, some 500 POWs and heavy

artillery pieces including four 88 mm guns and a battery of 105 mm howitzers

finally were taken. A Company, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, passed through

to clear the dense woods northeast of the town. Lieutenant Frank Kutak, though

wounded in both legs, nonetheless directed the company from his peep as the

armored doughs worked through the fir trees. A and B Company tankers of the 37th

Tank Battalion defended the left flank of the corridor. That same night the

division G-4, Lieutenant Colonel Knestrick, led a column of supply trucks and

ambulances through to Bastogne, escorted by D Company, 37th Tank Battalion's

light tanks. Wrote Patton happily—if with hyperbole—to his wife, Beatrice, "The

relief of Bastogne is the most brilliant operation we have thus far performed

and is in my opinion the outstanding achievement of this war."

CCB widened the

corridor on 27 December, even as CCA of the 9th Armored came up on the left

flank, and the 35th Infantry Division came up on the right. The Germans had

already called off their Ardennes offensive. The high drama of the breakthrough

to Bastogne had passed into a bitter struggle of attrition in the winter

snows.

The breakthrough to

Bastogne vividly demonstrated what an elite armored unit in action can do.

Though understrength

and fighting under less than favorable conditions of terrain and weather, the

4th Armored Division brought overwhelming force to bear at the decisive point.

The battalion task

force organization was modified to one of joint infantry-tank company teams

that leap-frogged one another in a column of companies to maintain the momentum

of the attack.

The reserve company

passed through to attack the next objective even before the first objective had

been secured, keeping the enemy off guard.

The tanks'

gyrostabilizers enabled them to smother the defense with fire while moving

across the battle area, and leaning into friendly fire gave the defenders no

chance to recover.

Pre-planned and

hip-shoot artillery concentrations, air strikes, and organic supporting bases

of fire further overwhelmed the defenders.

True, such cavalier

tactics would be less successful against a well-prepared defense; but in this

instance, the Germans were not given time to prepare. Nonetheless, the

principle of bringing the full force of infantry, armor, artillery and air

power to bear at the point of the main effort remains valid today.

Of particular note is

the quality of personal leadership, both in direction and by example. The

company and even battalion commanders were well forward or leading in their

combat vehicles, providing leadership up front at the decisive point. Orders

were oral, simple and of the general "mission-type." This encouraged

initiative on the part of junior officers who knew where to go and were

confident their commanders were with or right behind them.

Lastly, at a time when

many were bewailing the inferiority of the American Sherman tank, the 4th

Armored maintained confidence in themselves and their equipment. For "armor"

was a concept, of a combined arms team, and when all elements were brought to

bear, they were bound to prevail.

Source Materials

4th Armored Division

operations are based on unit diaries, journals and after action reports, U.S.

Army Armor School special studies, Military History Institute oral history

projects, and published sources. Research in these materials was supported, in

part, by an Ohio State University, Newark Campus, research grant.

Drs. John Slonaker and

Richard Sommers and Ms. Phyllis Cassler of the U.S. Army Military History

Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, were very helpful, as was Mr.

William Hansen, Librarian of the U.S. Army Armor School, Fort Knox, Kentucky.

Interviews with

veterans were facilitated by Samuel Schenker and the late Frank Paskvan of the

4th Armored Division Association.

Correspondents include

Major Generals Edward Bautz Jr. (37th Tank Battalion) and DeWitt C. Smith Jr.

(B Company, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion); Colonels (Retired) Robert

Connolly (4th Division Adjutant and G-1), William Dwight (37th Tank Battalion),

and H. Ashton Crosby (53rd Armor Infantry Battalion); Charles Boggess (C

Company, 37th Tank Battalion) and especially Col. (Retired) James H. Leach (B

Company, 37th Tank Battalion) who helped revise the manuscript.

|

| 4th Armored Division advance to Bastogne, 25-27 December 1944. |

|

| An M4 medium tank of the 4th Armored Division, partially camouflaged with white paint, during the race to reach Bastogne. |

|

| Soldiers of the U.S. 28th Infantry Division are welcomed by the people of Bastogne, as they arrive there in September 1944. |

|

| American M4 medium tank amongst the ruins of a Belgian village. |

|

| U.S. Army tanks and vehicles take cover in a Belgian town during the German winter offensive that precipitated the Battle of the Bulge. |

|

| Much of the civilian population of Bastogne left the town with the approach of battle. Here, some of the townspeople, now refugees, seek safety. American troops have halted along the street, where no snow has fallen as of the date of this image. |

|

| Manning a lonely outpost along a road leading into Bastogne, soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division point their bazooka in the direction of an expected German attack. |

|

| Their rifles slung over their shoulders, three men of the 101st Airborne Division walk down a rubble-strewn Bastogne street past the bodies of fellow soldiers killed by German bombing the previous night. This photograph was taken on Christmas Day, 1944, and the beleaguered defenders of the town were relieved the following day. |

|

| American troops on a bombed-out street in Bastogne. |

|

| Supplies moving through Bastogne, 22 January 1945, on their way to the front-line troops. |

|

| GIs in a jeep stand guard at a cross-roads near Bastogne as the bodies of two Americans lie in the field where they fell. December 1944. |

|

| Two American soldiers man a foxhole near Bastogne with a .50-caliber machine gun which has been dismounted from a vehicle. Note the extra machine gun barrel at the left, propped up on two ammo boxes for cooling. A bazooka can also be seen to the right of the machine gun. |

|

| 4th Armored Division tanks deploy on the road to Bastogne. |

|

| Casualties on the road to Bastogne. |

|

| Crew of M4A1 tank of the 4th Armored Division add foliage to their vehicle in order to improve its camouflage, Winter 1944. |

|

| Lt.Col. Creighton W. Abrams, Jr, CO, 37th Tank Battalion, December 1944. |

|

| Members of the 44th Armored Infantry, supported by M4 medium tanks of the 6th Armored Division, move in to attack German troops surrounding Bastogne, Belgium, 31 December 1944. |

|

| On the day after Christmas, 1944, Douglas C-47 transport aircraft drop provisions to American troops occupying Bastogne. |

|

| M8 howitzer motor carriage, with white sheets for winter camouflage, Bastogne, December 1944. |

|

| Weary troopers of the 101st Airborne Division march in two columns along a road on the outskirts of the Belgian crossroads town. |

Award of Bronze Star and Purple Heart to Pvt. Alfred E. Odle, 8th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored

Division: On the evening of 21/22 December, Pvt Odle participated in his unit's

drive north in an attempt to open the ring around Bastogne to relive the

defenders of the city. On 22 December 1944, as part of III Corps, the 4th Armored

Division was assigned the mission to advance northward to open a corridor into

Bastogne. They were to use the avenue of attack between the

Neufchateau-Bastogne Highway and the Aarlon-Bastogne highway and advance

northward as quickly as possible. The 8th Tank Battalion was part of Combat

Command B, and owned the western sector of the attack. They were to use the

north-south secondary roads in their advance. According to Cole's narrative of

the attack in the U.S. Army's Green Book series:

At

0600 on 22 December (H-hour for the III Corps counterattack) two combat

commands stood ready behind a line of departure which stretched from

Habay-la-Neuve east to Niedercolpach. General Gaffey planned to send CCA and

CCB into the attack abreast, CCA working along the main Arlon-Bastogne road

while CCB advanced on secondary roads to the west. In effect the two commands

would be traversing parallel ridge lines. Although the full extent of damage

done the roads and bridges during the VIII Corps withdrawal was not yet clear,

it was known that the Sure bridges at Martelange had been blown. In the event

that CCA was delayed unduly at the Sure crossing CCB might be switched east and

take the lead on the main road. In any case CCB was scheduled to lead the 4th Armored

Division into Bastogne.

On

the lesser roads to the west, General Dager's CCB, which had started out at

0430, also was delayed by demolitions. Nonetheless at noon of the 22d the 8th

Tank Battalion was in sight of Burnon, only seven miles from Bastogne, nor was

there evidence that the enemy could make a stand. Here orders came from General

Patton: the advance was to be continued through the night "to relieve

Bastogne." Then ensued the usual delay: still another bridge destroyed

during the withdrawal had to be replaced, and it was past midnight when light

tanks and infantry cleared a small German rear guard from Burnon itself.

Wary

of German bazookas in this wooded country, tanks and cavalry jeeps moved

cautiously over the frozen ground toward Chaumont, the next sizable village.

Thus far the column had been subject only to small arms fire, although a couple

of jeeps had been lost to German bazookas. But when the cavalry and light tanks

neared Chaumont antitank guns knocked out one of the tanks and the advance

guard withdrew to the main body, deployed on a ridge south of the village.

Daylight was near. CCB had covered only about a quarter of a mile during the

night, but because Chaumont appeared to be guarded by German guns on the

flanking hills a formal, time-consuming, coordinated attack seemed necessary.

During

the morning the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion and the twenty-two Shermans of

the 8th Tank Battalion that were in fighting condition organized for a sweep

around Chaumont to west and north, coupled with a direct punch to drive the

enemy out of the village. To keep the enemy occupied, an armored field

artillery battalion shelled the houses. Then, as the morning fog cleared away,

fighter-bombers from the XIX Tactical Air Command (a trusted friend of the 4th

Armored Division) detoured from their main mission of covering the cargo planes

flying supplies to Bastogne and hammered Chaumont, pausing briefly for a

dogfight with Luftwaffe intruders as tankers and infantry below formed a spellbound

audience. While CCB paused south of Chaumont and CCA waited for the Martelange

bridge to be finished, the Third Army commander fretted at the delay. He

telephoned the III Corps headquarters: "There is too much piddling around.

Bypass these towns and clear them up later. Tanks can operate on this ground

now." It was clear to all that General Patton's eye was on the 4th Armored

Division.

Apparently Odle was wounded some time during the evening of

21/22 December either while the Battalion was assembling for the attack or

moving forward. He stayed with his vehicle until the situation stabilized and

then he was evacuated and eventually made his way to a field hospital where he

was treated. It is interesting to note that the HQ got his ASN wrong and the

Field Hospital labeled the place of injury as Germany, and the date as 23 December.

Clerical errors of this type were common. Judging by the location of Hotte on

the map (blue arrow), it is likely that the Bronze Star citation is correct, as

the unit had already advanced a few kilometers to the north near Chaumont by

the 23rd.