by Kemp Tolley, Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy (Retired)

By late January 1942, Surabaya, Java, was the last remaining Far East Allied base of any real importance. As is usually the case, those of us there in the junior ranks knew no more of the actual state of affairs than one's own eyeballs assessed. The high command was not much better off. Japanese planes controlled the air. P-36s, P-40s and Brewster Buffaloes had no chance against the superb Zeros. Where were they coming from? Admiral Nagumo's powerful carrier force—the one that had hit Pearl? Where would the next landing be? Nobody knew.

The small Allied naval forces had been dealt a staggering blow when on 10 December the British battleship Prince of Wales and battlecruiser Repulse had gone down off Malaya in short order under enemy bombs and torpedoes. There remained only a few cruisers: British Exeter, Australian Perth and Hobart, American Boise, Houston and Marblehead Dutch de Ruyter and Java, and a handful of destroyers, the thirteen American ones of World War I vintage and lacking any anti-aircraft armament worthy of the name. The dozen small Dutch subs had taken heavy losses and the remaining crews were exhausted. As for the twenty-seven American subs, they might as well have been on the moon; their torpedoes were next to worthless. All were joined in combined command under U.S. Admiral Thomas C. Hart, who operated under enormous handicaps. There was no means of effective communication between ships of various nationalities, no common maneuvering doctrine, all compounded by a conflict of ideas as to how this little group of heterogeneous ships could be best utilized.

I had arrived in Surabaya on 23 January, skippering the largely Filipino-manned two-masted schooner USS Lanikai. We had island-hopped from Manila in just less than a month, narrowly evading Japanese naval and air units en route. Surabaya seemed to be safety at last. The big, modern heavy cruiser Houston lay alongside Holland pier and a number of Allied destroyers dotted the harbor. To my uninformed mind this seemed like the end of the great retreat and the place to begin the long march back.

The cruise south had left my small store of khaki uniforms in tatters, so I went aboard Houston for replacements from her small stores. Coming ashore, as I went aboard, was Commander Paul Talbot, his face beet-red from exposure to the sun. I found the ship jubilant over the report he had just made as commander of our first offensive foray against the enemy. For all its modest size it had been the biggest American sea battle since Santiago and our first naval victory in a war where some sort of triumph was desperately needed to boost a sadly drooping morale.

The Japanese had found the almost unopposed occupation of Tarakan, Borneo, so unexpectedly easy that they had speeded up their next operation, the capture of oil-rich Balikpapan, next down the coast. The U.S. submarine Sturgeon had spotted the force en route and emptied her forward tubes in a spread. There were two flame-accompanied explosions seen through the periscope, giving rise to the sub's laconic report that, "Sturgeon no longer virgin." Unfortunately, as post-war information revealed, Sturgeon's lost virginity resulted in premature twins. The villain? Faulty torpedoes, most of which in those earlier days were duds or prematures that all but killed the effectiveness of American submarines for offensive purposes during the war's first two years.

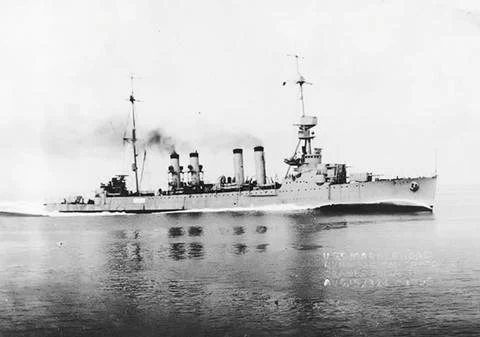

Though making no kills, at least Sturgeon's information gave the Allies a target. But their quiver was far from full and the bow weak. Cruiser USS Boise, escorted by one destroyer, was headed for repairs at Tjilatjap, on Java's south coast. She had run onto a submerged pinnacle on 21 January. Coral formations grew with the speed of summer cabbage in that tepid sea, where Japanese "fishermen," looking for something more over the decades than just the finny tribe, were more familiar with Indonesian rocks and shoals than their stay-at-home opponents.

Boise had been part of U.S. Rear Admiral William A. Glassford's striking force of old light cruiser Marblehead and six World War I destroyers, all the Allies could muster for the defense of the east flank of an island chain 3,000 miles long. Of all the Far East ships, only Boise was radar-equipped, so her loss was serious.

Marblehead, to which Glassford shifted his flag, had one turbine out of commission and could make only 15 knots. But she and the remaining destroyers filled up on Boise oil and set off north to beard the dragon.

Four destroyers charged on ahead, Marblehead staggering along in the rear to provide support for the "cans" on their withdrawal in case of enemy pursuit. "Good luck going in, God speed coming out!" radioed Rear Admiral William Purnell, commanding all U.S. Asiatic Fleet ships. Allied overall naval commander Admiral Hart, who held a somewhat dim view of Glassford's general abilities as a combat commander, took care to direct Commander Talbot, division commander, to take charge. Then, in characteristic Hart form, he gave the final order, "Attack!" This was expanded by Talbot into, "Torpedo attack. Hold gunfire until fish are gone. Use initiative and prosecute the strike to your utmost."

That they did, opening the engagement against the wholly surprised Japanese at about 3 a.m., 24 January. Dutch air strikes the previous day had lit fires ashore that perfectly silhouetted the targets afloat. This was a melee in the full sense of the word. Twisting and turning at full speed through the transport lines, most of the torpedoes were fired at an unusual point-blank range. The few that connected, coupled with a lack of gunfire, gave the Japanese escort commander the idea they were being attacked by submarines off the harbor entrance. So he hightailed it out after them, leaving his charges wholly unprotected other than by their own feeble armament and several small patrol vessels.

Torpedoes expended, the Americans doubled back on erratic tracks, using their 4-inch guns, with the by now thoroughly confused enemy shooting at each other as well as at their elusive attackers.

The score was, unfortunately, not impressive: four transports out of twelve, plus a patrol boat, plus damage to other ships. But it was a plucky, well-handled effort with old ships, our first victory at sea in a war that so far had been all the other way. The tragedy was that ill luck had robbed the Americans of what might have been total annihilation of a sizable enemy force, had the two cruisers been on hand in proper operating condition, supported by aircraft then available on Java.

But much had been gained in both morale and knowledge. It was brought sharply home that such close-in tactics would not work with torpedoes. The run, in some cases, was too short for them to arm the exploders. In any case, the change of bearing was at such a high rate that the tubes could not be trained rapidly enough for effective aiming. Due to the violent turns at high speed, too often the deck guns could not be brought to bear in the poor light, which made it near impossible to see through the telescopic sights at targets which whizzed by at a high relative speed. The doctrine was perfect; the technique needed brushing up.

It is interesting to speculate on what might have been the outcome in the Far East had the Allied forces been properly coordinated by timely establishment of the combined command, to allow setting up joint signals, tactics, and, above all, taut military decisions with totally unified air, sea and ground effort. But that was not to be. Divided we fell, to suffer a humiliation that saw us evicted from the Far East not only for the relatively short duration of the war, but perhaps for all time. Militarily, the Yellow Man had come of age.

|

| Boise (CL-47) anchored in harbor, circa 1938-39. |

|

| Houston (CL-30) probably photographed in 1930, at the time of her completion. |

|

| Houston photographed during the early or middle 1930s. |

|

| Houston at Tsingtao, China, on 4 July 1933, "dressed overall" for the holiday. She is flying the four-star flag of Admiral Montgomery M. Taylor, Commander in Chief Asiatic Fleet, at her forepeak. |

|

| Houston in Manila Bay, Philippine Islands, in 1940-41, after her final modifications. |

|

| Houston officers and crew, circa 1931-1933, with her band seated on deck in front. Houston's Commanding Officer, Captain Robert A. Dawes, is seated in the center, behind the life ring. |

|

| Houston's starboard 5"/25 guns in action, during anti-aircraft battle practice off Chefoo, China, 1932-33. |

|

| President Franklin Delano Roosevelt seated in the well deck of Houston, with a shark he caught in Sullivan Bay, Galapagos Islands, July 1938. A sailfish is being hoisted up in the left distance. |

|

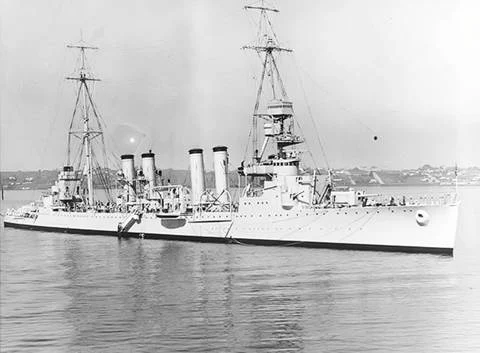

| Marblehead (CL-12) steaming at top speed during trials, 15 August 1924. |

|

| Marblehead being prepared for launching at the William Cramp & Son shipyard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 9 October 1923. |

|

| Marblehead in harbor, circa the early 1930s. The location may be San Diego, California. |

|

| Marblehead underway in San Diego harbor, California, 10 January 1935. Photographed from USS Dobbin (AD-3). |

|

| Marblehead in a Far Eastern harbor, circa the late 1930s. |

|

| Marblehead underway at sea, 10 May 1944. |

|

| Dutch cruiser De Ruyter deployed in the defense of Java, 1942. |

|

| Map of Naval Battle of Balikpapan, January 23-24, 1942. (Office of Naval Intelligence, U.S. Navy) |