by Cal Ritchey

The letter entrusted to Captain Ilia Tolstoy and Lieutenant Brooke Dolan II, in July 1942, may have been one of the most unusual pieces of mail to leave Washington over the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The strangest thing about the letter, aside from its destination—Lhasa, Tibet—was the addressee: Jeisum Jampel Ngawang Lobzang Yishey Tenzing Gyatso. The name belonged to a Tibetan child born on 6 June 1935, who in 1940 was installed as the 14th Dalai Lama, secular and religious ruler of Tibet's population.

Tolstoy and Dolan, both members of the fledgling Office of Strategic Services (OSS), had been assigned to carry the letter to the Dalai Lama as part of a two-pronged mission with both military and diplomatic implications.

There were sound reasons behind the trip, though it's not clear exactly who—or which group—originated the mission. In April 1942, the Japanese had succeeded in cutting the Burma Road at Lashio, near the Chinese border. Since nearly all military supplies for Chinese and Allied forces in China were shipped via the Burma Road, loss of the route was a serious blow to the prosecution of the war in China, and military planners in Washington, India, and China were anxiously searching for an alternate route.

Tolstoy and Dolan were charged with delivering the letter from Roosevelt to the Dalai Lama, which would initiate informal diplomatic ties between the two nations, and hopefully would enable the Army officers to carry out the second—and more important—part of their mission: to investigate the possibility of transporting supplies from India to China by way of Tibet.

Because the mission was not only dangerous—it meant months of riding over treacherous mountains—but was to be kept secret for strategic reasons, William J. "Wild Bill" Donovan, head of the OSS, was handed the task of getting the job done. In turn, Donovan chose Tolstoy to lead the expedition; Tolstoy selected Dolan as his second man because Dolan had some experience as an explorer in western China during the 1930s.

Very little was known about Tibet in American circles. In fact, in 1942 a club of Americans who had visited Tibet could have met comfortably in a closet. They included an ex-diplomat named Rockhill, who went to Tibet during the later years of the nineteenth century; Suydam Cutting, an explorer, and his wife, in the 1930s; and Theos Bernard, an Arizonian turned Buddhist monk, also in the 1930s.

In the opening decade of the twentieth century, however, the British had engaged in a mini-war against Tibet, and had won trade rights, and it was the British who had the most knowledge of the country, though they had no real authority there.

In a letter dated 2 July 1942, Donovan wrote to Secretary of State Hull requesting State Department assistance for Tolstoy and Dolan in negotiating British permission to leave India and enter Tibet—one right which the British did exercise.

On 3 July, Hull wrote to Roosevelt informing him of the mission and enclosing a draft of a letter for the President's signature, which Tolstoy and Dolan were to carry to Tibet.

The text of the letter (printed on page 625 of the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1942, China, series published by the U.S. State Department, Washington, D.C.) was nothing exciting:

Your Holiness:

Two of my fellow countrymen, Ilia Tolstoy and Brooke Dolan, hope to enter your Pontificate and the historic and widely famed city of Lhasa. There are in the United States of America many persons, among them myself, who, long and greatly interested in your land and people, would highly value such an opportunity.

As you know, the people of the United States, in association with those of twenty-seven other countries, are now engaged in a war which has been thrust upon the world by nations bent on conquest who are intent upon destroying freedom of thought, of religion, and of action everywhere. The United Nations are fighting today in defense of and for preservation of freedom, confident that we shall be victorious because our cause is just, our capacity is adequate, and our determination is unshakable.

I am asking Ilia Tolstoy and Brooke Dolan to convey to you a little gift in token of my friendly sentiment toward you.

With cordial greetings, (etc.),

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The gift was a $2,800 gold chronographic watch.

The letter was innocuous, and gave no hint of the true nature of the Tolstoy/Dolan mission—nor did it mention that the two men were in fact U.S. Army officers. This was at the specific request of Donovan; in his 2 July letter to Hull, Donovan had said that "we feel it desirable to avoid any mention of the military status of these two men in any negotiations."

In the July heat of Washington, the two men left to begin their mission. The first stage of the trip was by air to Delhi, India. Donovan saw them off at the airport personally; possibly he handed them Roosevelt's letter at the last minute.

The two men carried 290 pounds of equipment, plus 27 pounds each of personal gear. Tolstoy carried a camera, and took some 2,500 photographs during the trip.

In India they reported to Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell, commander of the China-Burma-India theater; Stilwell had been advised of the mission and apparently supported the effort. Tolstoy and Dolan were to keep Stilwell informed, as much as possible, of the progress of their journey.

Once in Delhi, they opened negotiations with Tibetan officials through Frank Ludlow, Additional British Political Officer for the Tibetan area, who was stationed in Lhasa. Most of the Delhi-Lhasa communication was probably by mail; there is no evidence of a telephone line connecting Lhasa with any area outside the country, though there was a telephone from Gyantse—first major town on the road to Lhasa, and also the point of the farthest British military outpost in the country—to Lhasa. In any case, the telephone would have been unreliable; the Tibetans frequently appropriated the copper wire, which came in handy for all sorts of non-communicatory uses.

By September 1942, Tolstoy and Dolan had received the okay to go as far as Lhasa. They left Delhi by train through Calcutta to Siliguri, near Darjeeling, where a tiny bit of India pokes northward between Nepal and Bhutan to Sikkim on the Tibetan border. At Siliguri they acquired an interpreter named Sandup, who brought his wife and infant daughter along for the ride.

In a National Geographic article of August 1946, Tolstoy reported that they drove in old Ford touring cars to Gangtok, the jump-off point for expeditions into Tibet. At Gangtok they were briefed by Sir Basil John Gould, Political Officer for Sikkim and British Representative for Bhutan and Tibet. Gould spoke Tibetan, and despite his sixty years, had made the difficult journey to Lhasa several times.

After hiring a pack train from the Maharaja of Sikkim, the party—now increased to seven by the addition of two local natives as cook and camp boy—left Gangtok in October.

At Yatung, the first overnight stop in Tibet which could be called a village, they were initiated into the harrowing round of parties which the Tibetans seemed anxious to give and receive where any governmental function was involved. Here they received the 'Red Arrow Letter,' a piece of red cotton cloth about 16 inches by 24 inches. It was a pass sent by the Dalai Lama; carried by an outrider a day or two in advance of the main party, it served to alert each village that an important party of travelers was approaching.

In Gyantse they were met by Major Gloyne, acting British Trade Agent, Lieutenant Finch, and Dr. G. H. F. Humphries, as well as a color guard of Indian Army sepoys. On the second day at Gyantse, Dolan came down with pneumonia, and despite sulfa treatments from Humphries, the trip was delayed almost a month. Tolstoy did manage to use the telephone two or three times to talk to Ludlow in Lhasa, however. On 4 December, the party, now accompanied by Dr. Humphries and two Tibetan soldiers sent as guards started for Lhasa.

They arrived at Lhasa about a week later, and were met by Ludlow, H. Fox, a British radio operator, and various members of the Tibetan government. Chinese delegates were there as well: the Chinese had had official representatives in Tibet for many years, off and on, and in fact China regarded Tibet as an autonomous region of China—a point which was to present a problem later.

After the requisite round of parties, Tolstoy and Dolan were informed that they were to meet with the Dalai Lama at 9:20 a.m. on 20 December—an hour chosen by court astrologers as being the most auspicious.

At the appointed hour, Tolstoy and Dolan appeared at the Potala, the 1,000-roomed home of the Dalai Lama, and were briefed on court protocol before being led into the throne room, where, Tolstoy reported, the young Dalai Lama sat sternly despite his youth, accompanied by the Regent of Tibet, an older man appointed to rule the nation until the Dalai Lama became of age at eighteen.

The traditional rituals were observed, including the transfer of Roosevelt's letter from Tolstoy to the Dalai Lama, thus completing the first part of the mission. It also marked the first time a President of the United States had communicated with a reigning Dalai Lama. In addition to the gold watch, Tolstoy and Dolan presented their own personal gift: a silver ship model. (The Dalai Lama later provided gifts for Roosevelt, including three rare gold Tibetan coins.)

With the rituals out of the way, the official reception was declared at an end, but Tolstoy and Dolan were granted a private half-hour audience with the Dalai Lama. Neither the Foreign Relations series, nor Tolstoy's National Geographic article records what was said, but at some point during their stay in Lhasa the Tibetans asked for a powerful radio transmitter; a request which caused some consternation in the State Department, who were afraid the Chinese would read into the gift official United States recognition of Tibet as a sovereign nation. (Roosevelt's letter had carefully been addressed to the Dalai Lama as head of the religious organization of Tibet, rather than in his governmental function, for that reason.) The radio was eventually delivered in November 1943.

In January, Tolstoy and Dolan made what appears to be a second request to be allowed to travel on through Tibet to China. The indications are that the two men waited until they were in Lhasa before attempting to pressure the Tibetan government for permission to finish their trip.

The clues are contained in a stilted and querulous letter from the Tibetan Foreign Office to Tolstoy and Dolan, and reprinted in the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1943, China volume, page 622:

On the 21st day of 12th month [corresponding to January 1943] you two came to the Foreign Office and brought a letter. We sent it to the Regent through Kashag. When you arrived at Delhi the British Foreign Office, through Mr. Ludlow, said the two American gentlemen wanted to come to Tibet with the purpose of giving a letter and present to the Dalai Lama from Mr. Roosevelt. When the letters would be delivered you promised to return to India if the Tibetan Government does not want you to go to China. Now you said that you have received a telegram from the American Government saying that you must go to Kansu County of Lanchow, and ask Tibetan Government to allow you to go straight to China.

This is the first time that friendly relations were established between Tibet and the U.S.A. and Mr. Franklin D. Roosevelt also has sent letter and presents to the Dalai Lama. For above reasons the Tibetan Government allows you to go through and will not set a precedent which other foreigners can claim. So according to your wishes, you and your servants can proceed via Nagchu to Jyekundo and up to Sining. There are many dangers from robbers and thieves, so we are sending one of our monk officials or lay officer and one sergeant of Tashi Fort and five soldiers by the order of the Tibetan Government.

13th Day of 1st month, Water Sheep Year [corresponding to February 1943].

The wording of the letter seems to indicate that the question of the Chinese trip had either not been made clear previously, or had been left up in the air; the tone of the letter may be a reaction to the telegram, which may have been more firmly worded than prior requests, if there were any.

In any event, Tolstoy and Dolan left Lhasa in mid-March. Sandup, their interpreter, and his wife and daughter, turned back to India, and were replaced by two more Tibetans. The group marched north and east out of Lhasa, and on 21 March 1943, they crossed the upper Kyi River near Phongdo, about four days march from Lhasa.

By 3 April, they had crossed the divide of Langlu La, at 15,000 feet, which separates the Brahmaputra and Salween river systems. On 5 April they reached Nagchu Dzong, administrative center of northern Tibet, where they picked up additional supplies which had been sent ahead from Lhasa.

On 7 April they encountered their first serious snowstorm. They also met a huge tea caravan coming from Yushu in China, a 400-mile trip from Nagchu Dzong. The caravan had had one thousand yaks and twenty-five ponies when it left Yushu four months earlier; now it was down to seven hundred yaks and fifteen ponies, an indication of the difficulty of travel in the area.

They reached the eastern limits of the Dalai Lama's authority, a town called Pachen, on 19 April; here the Tibetan soldiers were sent back to Lhasa. By prior arrangement, a contingent of Chinese troops was to have met the party, but never appeared, and the native members of the Tolstoy/Dolan group refused to go on unless Tolstoy hired twenty-five riflemen to guard the travelers through the next few hundred miles, which was known to be infested with even more bandits than was normal for that part of the world.

On 23 April they began to climb to Tsangne La, a 16,000-foot pass rarely open in January, February or March; this pass would be a potential problem for any convoys supplying China. (The headwaters of the Salween, Yangtse and Mekong rivers arise in this general area.)

Shortly after crossing the pass, they drove off a band of strangers with machine gun fire, though there were apparently no injuries on either side.

On 12 May they encountered a unit of Chinese Mohammedan soldiers under the command of Major Ma Ying-Hsiang, who said he had been searching all the passes in the area for the group. These soldiers probably were the unit detailed to meet Tolstoy and Dolan at Pachen.

By 15 May they had been fifty-eight days en route from Lhasa, and at Yushu (Jyekundo) they sent a wireless message to Sining, still a month's travel to the northeast, to be forwarded to Stilwell in India, advising the general that they had made it as far as China.

They rested at Yushu for a few days before leaving there in late May. By 7 June they had reached Tra La, a small village between the Yangtse and Yellow Rivers, where Dolan shot a large bear. (In this area they saw as many as nine bears in one day, Tolstoy reported.) They crossed the Yehmatan Plains with its vicious swamps, where Tolstoy says they "camped for three nights virtually in water."

It took them a day and a half to cross the Ta River, 17 and 18 June; though the river was only 300 feet wide, it was exceptionally swift because of recent heavy rains. From the Ta they moved on to Tahopa Fort, where neither the telephone nor telegraph were operational. Tolstoy reported of Tahopa that sometimes, in summer, trucks were able to struggle up the rutted trails to reach the fort.

On the 89th day out of Lhasa they reached Hwangyan, only a few miles west of Sining. Shortly after passing Hwangyan, Tolstoy and Dolan left their ponies in the care of the native members of the party and rode in relative luxury into Sining in the car sent out by the governor of Tsinghai Province.

It had taken Tolstoy and Dolan nine months—October to June—to make the 1,500-mile trip, though they were delayed one month in Gyantse by Dolan's illness, and two months in Lhasa.

Technically, the mission had been a success in several ways: it had established some diplomatic ties between Tibet and the U.S., and it had proved that shipping goods through Tibet was at least possible. (In addition, Tolstoy may have prevented a Chinese-Tibetan war. On 17 April, he had sent a letter out to Merrell, Charge in India, reporting on rumors of Chinese and Tibetan troops moving toward each other. Subsequent investigation by authorities in India and China brought denials from the Chinese of any intent to invade Tibet.)

The feasibility of the route was another matter. Tolstoy estimated that about four thousand tons per year could be carried over the route; other authorities put the figures as low as one thousand tons—virtually useless except as a source of morale for the Chinese.

After much negotiation, Tibetan authorities agreed to give permission to use the route as long as no military goods—arms and munitions, etc.—were transported. Petroleum was acceptable, as was medicine and food, and a trial shipment of 50 tons was organized in India, but never sent.

The political factors involved in the decision to make use of the route were complicated. The Chinese claimed Tibet as part of their nation, and the U.S. could not deal exclusively with Tibet. On the other hand, Tibet considered herself independent; Tibetans were afraid to approve the route for fear that China would use the transport route as a way to solidify her claims on Tibet. But Tibet was also afraid not to approve the route, believing that China might then claim an act of aggression.

The Tibetans insisted on three-way negotiations dealing with the supply line: China, Tibet, and the United States. China refused any three-way discussion, believing that it might lead to U.S. recognition of an independent Tibet.

As late as mid-1944, the idea was still under consideration, but even though Tibet had long since given permission, the political problems were such that the idea was finally dropped.

Happily, it wasn't needed. The "Hump" airlift was moving thousands of tons each month into China, much more rapidly and with more certainty of delivery than any land route through Tibet could have done.

As far as Tolstoy, Dolan and their superiors were concerned, the mission was a success. Tolstoy was promoted to major (later to lieutenant colonel) and Dolan was promoted to captain. Tolstoy also received the Legion of Merit for "rare tact and diplomacy" in the execution of the mission.

Captain Dolan returned to China in 1945; he died there "in the service of his country," leaving his wife and seven-year-old daughter.

Lieutenant Colonel Tolstoy returned to civilian life; for a time he was associated with Marineland of Florida, and later entered private business in the Bahamas. Ilia Tolstoy died in 1970, at the age of sixty-eight.

A New York Times article on 2 June 1978 reported that the Jacques Marchais Center of Tibetan Art, at 933 Lighthouse Avenue, Staten Island, New York, was making plans to put on permanent exhibit a number of the 2,500 photographs taken by Tolstoy during his Tibetan mission.

|

| 14th Dalai Lama, at his enthronement ceremony, February 22, 1940 in Lhasa. |

|

| Captain Dolan (left) and Count Tolstoy inspect their equipment before undertaking their perilous equestrian journey from India, across the Himalayas into Tibet, and on to China. |

|

| Count Ilya Tolstoy, left, Captain Brooke Dolan, center, and a mounted Gurkha guide can be seen riding across Tibet in 1942. |

|

| Colonel Count Ilya Tolstoy (left) and Captain Brooke Dolan (right) are greeted by a Tibetan official. |

|

| Tibetan Cavalry welcomed Count Tolstoy and Captain Dolan when they rode into Lhasa on their secret mission to "Shangri-La." |

|

| Tolstoy's caravan climbed dangerous Himalayan mountain paths such as this one on their way to the Forbidden City of Lhasa. |

|

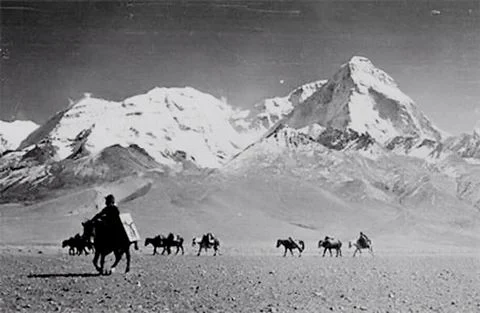

| A Tibetan outrider leads Tolstoy and his men into Tibet. |

|

| Loading the Riding Horses and Pack Mules on the river barge. |

|

| Lt. Col. Ilya Tolstoy and Capt. Brooke Dolan. |

|

| Lt. Col. Ilya Tolstoy and Capt. Brooke Dolan. |

|

| Tibetan officials such as these negotiated the possibility of allowing Roosevelt and Churchill to create a road from India to China via their mountainous kingdom. |

|

| The Stars and Stripes reach China. |

|

| Tolstoy (left) and Dolan (right) among Tibetan clergymen during 1942 mission. |

|

| Ilia Andreevich Tolstoy (1903-1970). |