The M5 13-ton high-speed tractor was a World War II era artillery tractor that was used by the US Army from 1942 to tow medium field artillery pieces.

Design

The M5 high-speed tractor was a fully tracked artillery tractor designed to tow artillery pieces that weighed up to 16,000 pounds (7,300 kg). It could tow the gun and carry the gun's ammunition, the crew and their equipment.

The M5 was developed from the prototype T13 high-speed tractor, it shared the latter's Continental R6572 in-line six-cylinder petrol engine which developed 235 horsepower (175 kW) at 2,900 rpm and, like the T13 before it, derived its tracks and its vertical volute spring suspension from the Stuart tank. The M5 had a maximum road speed of 35 miles per hour (56 km/h) with a range of 125 miles (201 km).

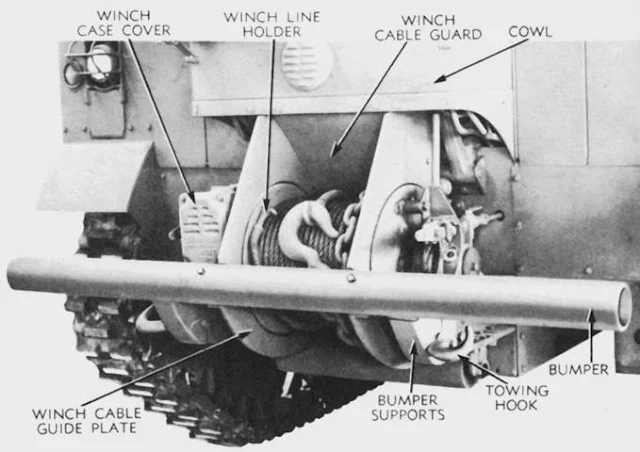

To assist in the movement and placement of its gun, the M5 high-speed tractor was equipped with a front mounted engine-driven winch that had a maximum pull of 17,000 pounds (7,700 kg) and was fitted with roller below the winch that permitted pulling of loads behind the tractor.

Type: Artillery tractor

Place of origin: United States

Used by:

US Army

Belgian Army

Japan Self-Defense Forces

Austrian Armed Forces

Yugoslav People’s Army

Lebanese Army

Pakistan Army

Wars:

World War II

Korean War

1958 Lebanon crisis

Lebanese Civil War

Designed: 1942

Manufacturer: International Harvester

Produced: May 1943-September 1945

Number built: 5,873

Variants: 5

Weight: 27,600 lb (12,500 kg)

Length: 5.03 m (16 ft 6 in)

Width: 2.54 m (8 ft 4 in)

Height: 2.69 m (8 ft 10 in)

Crew: 1 + 10

Armor: none

Main armament: 1 x M2 Browning machine gun

Engine:

Continental R6572 six-cylinder petrol engine

235 hp (175 kW) at 2,900 rpm

Power/weight: 15.0 hp/t

Suspension: VVSS

Operational range: 125 mi (201 km)

Maximum speed: 35 mph (56 km/h)

Production

The design of the M5 high-speed tractor was standardized in October 1942, with production being undertaken by International Harvester, the design was to evolve into five marks. The M5 was accepted into US Army service as the standard gun tractor used to tow the 105 mm Howitzer M2, the 4.5-inch gun M1 and the 155 mm howitzer M1. Standard ammunition stowage was:

105 mm howitzer M2 – 56 rounds

4.5-inch gun M1 – 38 rounds

155 mm howitzer M1 – 24 rounds

M5 high-speed tractor

Production of the original M5 high-speed tractor began in May 1943, running for 24 months with a total of 5,290 tractors produced. They had a simple folding top with side curtains for the protection of the gun crew from the elements, the driver was located in the front centre and there were inwards facing seats for total crew of 9. After 1944 the vehicles were fitted with the M49C ring mount that allowed it to be armed with an M2 Browning machine gun for local and air defense.

M5A1 high-speed tractor

Introduced in May 1945, the M5A1 high-speed tractor introduced a new steel cab with the driver moving to the front left and forwards facing seats for the crew for a total crew of 11. A total of 589 M5A1s were produced before production ceased in August 1945.

M5A2 and M5A3 high-speed tractors

Introduced after WWII, the M5A2 high-speed tractor and M5A3 high-speed tractor were updated M5s and M5A1s with a horizontal volute spring suspension system instead of the original vertical volute spring suspension and new tracks that were 21 inches (53 cm) wide compared to the older tracks that were 11.625 inches (295.3 mm) wide.

M5A4 high-speed tractor

The M5A4 high-speed tractor reorganized the ammunition stowage boxes along the sides of the vehicle for easier access.

Users

World War II

The M5 high-speed tractor entered service with the US Army in 1943 and was one of the primary medium artillery prime movers along with the GMC CCKW 2½-ton 6x6 truck and the Diamond T 4-ton 6x6 truck. In 1944, 200 M5s were provided to an appreciative Soviet Union for use by the Red Army who quickly rushed them into service.

Post-war

The US Army continued to use the M5 during the Korean War, retiring them shortly afterwards. Post-war surplus M5s were supplied to Austria, Belgium, Japan, Lebanon, Pakistan and Yugoslavia.

A number of M5 Tractors were used in British Columbia, Canada, as carriers for rock drills. The Chapman "Drilmobile", manufactured by Chapman Motor & Machine Shop of Delta, British Columbia was designed specifically for logging road construction.

Surviving Examples

Surviving examples of the M5 high-speed tractors of various marks can be seen at:

2 pieces in the Robert Gill Collection militarymuseum.at, Vienna, Austria

Marshall Museum, Lexington, Virginia.

45th Infantry Division Museum, Oklahoma City.

Museum of the American G.I., College Station, Texas.

Armourgeddon Tank Driving, Husbands Bosworth, Leicestershire, England.

Museum of the Kansas National Guard, Topeka, Kansas.

Arkansas National Guard Museum, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Lewis Army Museum, Fort Lewis, Washington.

A mostly intact but rusting M5 or M5A4 Tractor, complete with Continental engine, PTO winch, six 5-round side-mount ammunition lockers, and M2 Browning ring-mount can be found parked beside Route 96 in New York state, a few miles east of the town of Phelps. It has been recently removed from this location and its whereabouts are unknown.

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor prime mover. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor, upper front view. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor, upper front view with compartments opened. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor, upper rear view showing open powder boxes and outside-hinged rear doors. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor underside. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor driver’s controls. |

|

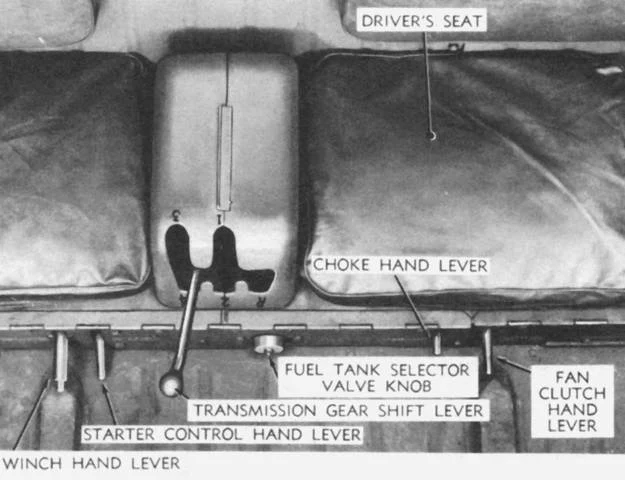

| M5 High-Speed Tractor controls at the front of the driver's seat. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor driver’s instrument panel. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor engine right side. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor engine left side. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor engine top view mounted in the vehicle. |

|

| Gar Wood Model US 15T winch on the M5 High-Speed Tractor. |

|

| Soldiers pulling 155mm howitzer with an M5 High-Speed Tractor, Camp Adair, Oregon, 1945. |

|

| M5 High-Speed Tractor dragging sleds of ammunition to the front on Saipan as a jeep equipped to lay wire waits on the side of the road. |

|

| Army personnel pulling a 155mm Howitzer with a International M5 High Speed Prime Mover during a test or demonstration. 1943. |

|

| The Soviet Union received almost 200 M5 High Speed Tractors in 1944 and, as being notoriously short in prime movers, instantly deployed them to their heavy artillery units. |

|

| Another M5 High-Speed Tractor in Soviet service. Both photos show them towing the Soviet 152mm ML-20 Howitzer. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor, artillery prime mover, with .50 cal. machine gun on ring mount. |

|

| Tractor, High Speed, 13-ton, M5, with canvas cover, towing 155mm Howitzer for visiting dignitaries. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor with cover and ring mount removed. |

|

| Presentation of the three main artillery prime mover high speed tractors (HST), circa 1944. From Field Artillery Journal, April 1944. |

|

| Field artillery M5 High Speed Tractors with 155mm howitzers in tow, preparing for D-Day, southern England, late May/early June 1944. |

|

| 13-ton High Speed Tractor, M5, towing a 155mm Howitzer, M1, on the Route Nationale 13 (RN 13), circa June 1944. |

|

| M5A1 High Speed Tractor towing the M1 155mm Howitzer, Germany, 1945. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor, artillery, and vehicles of the 90th Infantry Division prepare to cross the flooded Moselle River via a newly constructed treadway bridge, Cattenom, France, November 1944. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor pulling two M10 Ammunition Trailers, Biak Island, New Guinea, 8 June 1944. |

|

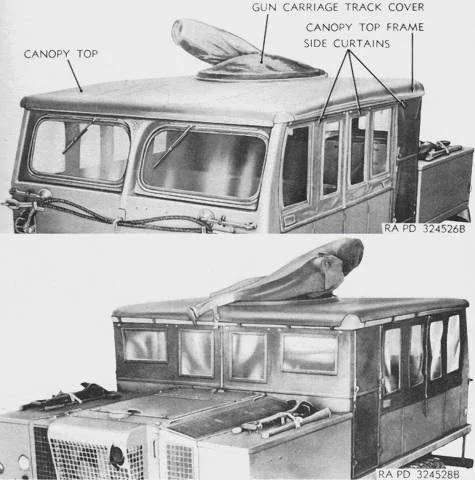

| M5 High-Speed Tractor with canopy top erected. |

|

| M5A1 High Speed Tractor, with a cab similar to the M4 High Speed Tractor, circa 1945. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor towing a 155 Howitzer M1. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor towing a 155 Howitzer M1 across a ponton bridge. |

|

| M5 high-speed tractor with canopy top and curtains. |

|

| M5 high-speed tractor with canopy top and curtains. |

|

| M5A1 High-Speed Tractor front view. |

|

| M5A1 High-Speed Tractor rear view with machine gun uncovered and the barrel secured. |

|

| M5A1 High-Speed Tractor driver’s controls. With the driver moved to the left front corner, the transmission's gear shift lever now appeared at his right instead of directly ahead. |

|

| M5A1 High-Speed Tractor. The shell boxes were moved to each side of the rear seat. Canvas covers were provided for protection when the boxes were not being loaded or unloaded. |

|

| M5A2 High-Speed Tractor. The new horizontal volute spring suspension dispensed with the frames attached to the hull, and dual wheels were used with the wide single-pin, center-guide track. |

|

| M5A2 High-Speed Tractor. A trailing idler wheel was retained with the suspension switch. |

|

| M5A2 High-Speed Tractor horizontal volute spring suspension is given here. The idler retained its own spring, and track tension was adjusted in a similar manner to the earlier suspension. |

|

| M5A3 High-Speed Tractor. The horizontal volute spring suspension was combined with the steel cab in the M5A3. |

|

| M5A4 High Speed Tractor, based on the M5A2 augmented with additional rearranged storage. The rearranged shell boxes lined the fenders and opened to the outside, easing access to their contents. |

|

| M5A3 high-speed tractor towing a 155mm “Long Tom” gun in Korea. |

|

| The M5 High Speed Tractor continued in use into the 1950s. A convoy with artillery prime movers in Korea. The leading vehicle is an M5 High Speed Tractor. |

|

| M5 High Speed Tractor, Fort Lewis Museum, towing a 155mm Howitzer. |