|

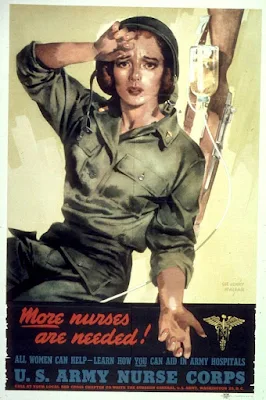

| "YOU ARE NEEDED NOW. JOIN THE ARMY NURSE CORPS." Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services. (03/09/1943 - 09/15/1945) |

Women have played an important role in the history of Fort Monroe over the years, but World War II was especially important as it was the first time in US Army history that women were officially allowed to serve in the Army, instead of simply as auxiliaries or “with” the Army, but not in it. This affected the status of both Army nurses and members of the Army Women’s Corps stationed at Fort Monroe. Women had unofficially filled many roles in the army for years. During World War I they were allowed official roles outside of the realm of nursing for the first time. However, in World War I the women serving with the Army, both as nurses and in other roles, still were not officially members of the military, and therefore did not receive benefits such as equal rank, pay, or veterans benefits.

This all changed during World War II. The Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps was established by Congress in 1942 as an auxiliary unit to the army, but in 1943 a new law was passed dropping the “Auxiliary” and women for the first time became full members of the army as part of the Women’s Army Corps in September 1943. (The Navy and Marine Corps had enlisted women during World War I). Thus by the time the first WAC officers arrived at Fort Monroe in late 1943, they were officially in the Army. According to Defender of the Chesapeake, “three second lieutenants [were] placed on duty with the post and two with the Coast Artillery School.” The first enlisted WACs arrived in January 1944. It seems that all the enlisted women at the fort were assigned to the Coast Artillery School.

There were also Army nurses stationed at Fort Monroe. These women had to wait slightly longer than the WAC to receive equal status to army men. They only received equality of rank, pay, and benefits in 1944, even though the Army Nurse Corps had been in existence since 1901. In 1944, there were twelve nurses stationed at Fort Monroe to staff the 139 bed station hospital according to an article published in the Altoona Tribune that May. The chief nurse was Lieutenant Elizabeth Steindel. She had entered the nurse corps with the (relative) rank of second lieutenant in July 1942, and was promoted to first lieutenant in October of that year. She served as chief nurse at Fort Monroe from April 6, 1943 to January 7, 1945, when was relieved by Captain Helen Jacobs in January 1945 in anticipation of being sent overseas. Steindel was still at Fort Monroe when she was promoted in Captain in April 1945. It is unknown if she was sent overseas before the war ended.

Some of the other nurses at Fort Monroe during World War II were Anna P. Heistand, Margaret W. Henninger, and Lillian B. Westerfield, who all received promotions to first lieutenant in April 1945, and Lois V. Ketran, who was promoted to first lieutenant in January 1945. Ketran was from Philadelphia and worked in the operating room at the fort’s station hospital.

Steindel was from Altoona, Pennsylvania. The article mentioned above described the physical exercises Steindel had her nurses participate in so that they would be ready for both the stress of their work at Fort Monroe and the rigors of potential deployments overseas. Although women at the time were officially barred from combat, nurses realized they were likely to be in harm’s way when sent overseas and wanted to be prepared. In September 1943, nurses at Fort Monroe started participating in “military drill and calisthenics,” and also had the use of tennis courts behind their quarters, a volleyball court, and an archery set. Although the tennis court is long gone, the nurses’ quarters, Building #167, still stands on Patch Road across from the hospital.

The nurses also had access to the officers’ clubs, which at the time were the Casemate Club, located in the Flagstaff Bastion, and the Beach Club, with beach access and a swimming pool, where the Paradise Ocean Club is today.

The clubs also offered other off-duty activities, and the nurses were usually allowed a half day a week off post. However, with only 12 nurses, the hospital would have kept them plenty busy as well. Each nurse had a daily seven hour shift, with about one full day off a month, and the possibility of leave every four months.

Although there were nurses at Fort Monroe before the WAC arrived, once they came, the WAC soon outnumbered the nurses. Although all nurses were granted officer ranks, the WAC included both enlisted and commissioned personnel. The first WACs officers arrived in late 1943. Eleven enlisted women arrived at Fort Monroe in January 1944. By the end of May, the contingent had grown to 58 WACs working for the Coast Artillery School, led by Lieutenant Mary E. Slack. The WAC was housed and fed separately from the men, and the unit included a staff of cooks, bakers, clerks, and others to make up a “normal company household” as a May 1944 Daily Press article termed it. Other women worked in “almost every non-combat duty to which soldiers are assigned… clerks and typists… artists and draftsmen … welders, parts clerks, drivers and a dispatcher in the motor pool; dark room technicians, a blueprint machine operator and motion picture projector operators.” Other positions open to them were listed to include “typists, draftsmen, artist, proofreaders, truck drivers and clerk-typists.” A February 1945 article, from the Hazelton, Pennsylvania, Plain Speaker listed other positions available in the WAC Detachment at the Coast Artillery School at Fort Monroe including linotype operator, photographer, photoengraver, retouch artist, stenographer, chauffeur, auto, file clerk, proofreader, message center clerk, messenger, and supply clerks.

Fort Monroe was not the only local post to have WACs. The Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation, in Newport News, Virginia, and Fort Story, near Cape Henry, also employed WACs, while Fort Lee near Richmond was a major WAC training center.

Most of the WACs at Fort Monroe were enlisted, but they still had access to recreation opportunities on post including “a modern theater [that] plays first-run motion pictures; two libraries,[…] a beach and tennis courts.” The article also specified that “two day rooms for recreation has [sic] been set up, one solely for the women’s use, and one to which they may invite their friends.”

Although Fort Monroe did not receive a WAC detachment until fairly late in World War II, the women clearly made an important impact on the fort, and, as advertising slogans of the day pointed out, each one also helped to “free a man to fight.” Army WACs, wherever they were stationed, helped break down gender stereotypes by taking jobs often previously held only by men. For example, women draftsmen, who were mentioned in both newspaper articles about the WAC at Fort Monroe, were extremely rare before World War II. Fort Monroe continued to have a WAC detachment until the Women’s Army Corps was disbanded in the 1970s and women were integrated into the army.

Army nurses were also breaking new ground during World War II. Even their physical fitness training at Fort Monroe was hammering away at gender stereotypes, due to the reasons given for the training described in the Altoona Tribune. The article was published only one month before D-Day, when US Army nurses were banned from landing on D-Day itself because of fears of bad press and the effect on home front moral if a nurse was killed or wounded that day (in contrast US Army nurses had landed on D-day in North Africa the year before, and British nurses went ashore on D-Day in Normandy in British sectors). However, the article frankly admits that “Army nurses, who in this war customarily minister to the wounded under fire and take the bumps of a combat soldier in anything from jeeps to transport planes, need and are getting more physical conditioning than ever before.” It later states that “if [Lieut.] Steindel has her way they will be in condition mentally and physically to go wherever the war may take them.”

Women played many important roles at Fort Monroe during World War II, from the more traditional role of nurse to newer jobs such as truck drivers and draftsmen. They contributed to both the work of Fort Monroe during World War II and to the opening of new opportunities for women. Civilian women also played important roles at Fort Monroe during World War II, such as with the fort’s YMCA and with the American Red Cross.

|

| "Nurses are needed now. Army Nurse Corps." Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services. (03/09/1943 - 09/15/1945) |

No comments:

Post a Comment