Our ships and aircraft sank many German submarines during the Great Patriotic War. One of them—the U-250—was raised by divers, towed to a wharf and dismantled. Our Navy obtained valuable data on the enemy's newest and most secret naval weapons.

The secret of acoustic homing torpedoes still had not been completely figured out by the British, and none other than Churchill appealed to Stalin with a message in which he requested that one of the captured torpedoes be handed over to the British Admiralty. Here the participants in the sinking, raising, and dismantling of the boat recount the events of those years.

The Sinking

Capt. 2nd Rank A. P. Kolenko (Reserves), former commander of the Guards Patrol Boat MO-103

Lieutenant Werner Schmidt was commanding officer of the U-250. In 1935 he had sailed as an officer on the battleship Schlesien and later on the cruiser Konigsberg. However, before the war the thirst for glory coaxed him into entering the Air Force. In 1939 he took part in the minelaying in the English Channel. Then, having become a bomber commander, he took part in raids on London, Liverpool, Glasgow, Belgrade, Suez and Alexandria. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Schmidt participated in aerial bombing attacks.

In 1942 he obtained a transfer to the submarine fleet, which then was still successfully operating in the Atlantic against the British. Going through accelerated training in 1942, Schmidt took command of the submarine U-250, which had been built at Kiel. However, he wound up cruising not the Atlantic but the Baltic. By that time, Capt. Schmidt had two Iron Crosses.

On 12 June 1944, the U-250 moved to the eastern part of the Gulf of Finland. Observing none of our ships in Nerva Bay, she moved on to Vyborg Bay. At 1240 hours on 30 June, she succeeded in sinking the motor patrol boat MO-105 and, seven hours later at 1940 hours, the U-250 had its inglorious end not far from Bjorko Zund.

As the prisoners (six, including Werner Schmidt) told us, the boat suffered serious damage after the explosives of the very first depth charges which we released. But because the engines were still operating, the captain still had hope of evading us. Soon one of the depth charges from the second series exploded directly next to the boat's hull. Water rushed into the resulting hole and quickly flooded the engine compartment. The batteries started giving off chlorine, and the men started fainting. Communication among the different compartments was disrupted. "It must be kept in mind that all of this happened so fast that I couldn't anticipate it beforehand," stated Schmidt during the interrogation. And so ended the first and last combat cruise of the German U-250.

The Raising

Capt. 3rd Rank A. D. Razuvayev (Reserve), former diver group leader

In early August 1944, the Black Sea Fleet Salvage Detachment in which I served was ordered to raise the U-250, which had been sunk at the northern inlet to Bjorko Zund.

It was planned to examine the boat, enter it, and remove documents and charts. For three days we attempted to carry out this mission in light diving gear, but due to the explosions the hatches were twisted and it proved impossible to open them. Then the command began to consider methods of raising the boat.

To prevent our raising the submarine, the German Naval Command ordered the Fifth Torpedo Boat Flotilla to drop thirty depth charges on her and lay twelve mines in the work area. Small submarine chasers and motor gunboats repeatedly repulsed enemy attempts to break through to the area where we were working. During the day, enemy guns fired upon our ships, so that we decided to work at night. The divers had to work five to seven hours per day under difficult conditions: storms, gunnery fire, and darkness.

When darkness set in, diver I. P. Fedorchenko slipped into the water, circled the boat, and established that it was lying on its bottom on the peak of a rock bank at a depth of 27 meters, with a stern trim of 5 degrees and a 14 degree list to starboard. The boat had substantial damage: a hole measuring approximately 30 square meters on the starboard side of the engine compartment (the right diesel had been ripped from its base and thrown toward the port side), a hole measuring approximately 2.75 square meters in the bow section, a dent on the starboard side of the first section (in the area of the torpedo tubes), a dent in the starboard side of the stern section, and the roof of the conning tower hatch was ripped off.

It was initially decided to raise the boat with two 200-ton pontoons. To this end, we cleared away two tunnels under the boat bottom and, removing stones from them, slipped two double 8-inch lines through the tunnels.

The raising began the next night. However, toward evening a force eight wind blew up and raised high waves. The pontoons flew up to the surface. The wind pushed them toward the enemy coast and tossed them onto a bar. Everything had to be done over again. Rather than repeat the first attempt to raise the boat, a new method was devised which used four pontoons instead of two.

Having recovered the pontoons which had been carried away that night, the next day we were already able to take advantage of a fog and resume work. However, the fog unexpectedly cleared away, and the enemy resumed his rapid shelling. Our supporting minesweepers quickly laid a smoke screen, but we had to move off.

During the next two nights we finished all preparatory work and on the third night began the general pumping of the pontoons. In two hours the water surface began to seethe and foam, and sparbuoys secured to the submarine bow and stern lay flat—it had begun to surface. Soon the conning tower could be seen out of the water, and after it appeared the deck, from which water poured with a roar.

The tug F-2 and the salvage ship Tsitsiliya, covered by the smokescreen laid by the submarine chasers, towed the U-250 to Koyvisto, where it was examined and the pontoons were securely strengthened and pumped fuller.

On 15 September the tugs towed the submarine to Kronstadt. This was accomplished by the salvage ships Sirena and Tsitsiliya, submarine chasers and motor patrol boats. They moved quite slowly—at a speed of two knots, so that the convoy took 35 hours to reach Kronstadt.

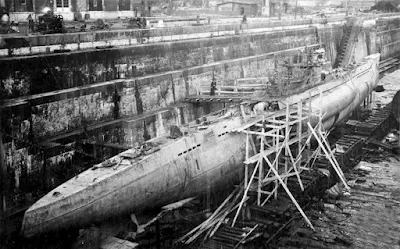

On the second day after arrival, the submarine was placed in drydock.

The Dismantling

My very first acquaintance with the submarine U‑250 led to the conclusion that it belonged to the VII-C series.

Upon inspection of the submarine it became clear that the bow section held racks containing the G7A steam torpedo, while the stern compartment contained a T‑V electric homing torpedo with a proximity fuse, a weapon which—like the fuse—was unknown to us. The No. 1 torpedo tube was empty (the torpedo fired from it had sunk the patrol boat MO‑105), but the others were loaded; in two other bow tubes there were G7E electric torpedoes, and T-V homing torpedoes were in one bow tube and in the stern tubes.

Obtaining information on the construction of the torpedoes required that they be removed from the tubes and be dismantled. This did not seem easy. First, as the commander of the U-250 had indicated, there were devices aboard the boat to explode it under certain circumstances. (In fact, we found more than twenty such devices in the battery compartment. However, fortunately for us, they were damaged and did not work.) And during removal of torpedoes even from the tubes in good working order they might explode because of such secret devices, so that this type of work was performed only by specially trained teams. They also informed us that the T-V torpedoes had camouflets (devices causing an explosion when attempts were made to dismantle them).

Secondly, removal of the torpedoes from the boat was complicated by the fact that all the tubes had been ripped from the flanges securing them to the pressure hull and had been substantially twisted, so that the torpedoes in them were wedged in. A torpedo lying on racks in the stern compartment had been knocked out of position and was blocked by the starboard electric propulsion motor, which had fallen on it. As a result, there were deep dents in the torpedo casing, one of the hand holes was ripped open, and the afterbody was filled with water. The torpedo loader in the stern section was completely wrecked, and the one in the bow section was heavily damaged.

Initially we decided to rebuild the torpedo loaders and install a special device to transfer the torpedoes from the submarine to the dock wall. Then we proceeded to the actual removal of the torpedoes and the raising of them to the wall. In addition, we had to allow for the fact that all of the torpedoes had inertial and proximity fuses and were armed. It was possible that while the submarine had been lying on the bottom as well as while it had been raised and towed to Kronstadt, streams of water might have flowed in through the slightly open bow torpedo tube shutters and turned the fuse spinners, thereby arming the torpedoes. The explosion of depth charges and the deformation of the torpedo tubes also affected the fuses. This made it impossible for us to tolerate not only sharp blows, but even the slightest shocks to the torpedoes.

During removal of the T-V torpedoes and one of the G7E torpedoes from the bow tubes, it was observed that the bolts of the tail sections of the torpedoes were sheared and that only electric cables and air lines were attaching them to the instrument sections. To prevent the cables from parting and the electrical circuits from being damaged, both parts of the broken torpedoes had to be joined by special attachments, for which large longitudinal windows had to be cut in the torpedo tubes by means of torches. The reinforced torpedoes were successfully removed from the tubes by use of a hand winch.

As we proceeded to unload the T-V torpedoes we knew that they might conceal booby traps. We were particularly aware that in some booby traps the Germans used a photo element which would cause an explosion when light penetrated the casing. Therefore, the torpedoes were dismantled at night under a red light.

After we succeeded in dismantling all the torpedoes safely, we began to study the apparatus removed from them. Naturally, the acoustic-guidance instruments and the influence fuses were of particular interest.

As a result of the studies performed we obtained valuable information not only on the acoustic system but also on other systems. Thus, it was shown that the G7A and G7E were fitted with the previously unknown FAT and LUT maneuvering instruments.

|

| U-250 in the dry dock at Kronstadt. |

|

| The crew of MO-103 which was involved in the sinking of the U-250. |

|

| On 14 September 1944 the submarine was raised, towed into Koivisto and then into Kronstadt where it was put in dry dock. |

|

| The heavily damaged section of U-250. |

|

| U-250. |

|

| U-250. |

|

| U-250. |

|

| Removing the dead bodies of German submariners. |

|

| Removing the dead bodies of German submariners. |

|

| Removing the dead bodies of German submariners. |

|

| Removing the dead bodies of German submariners. |

|

| U-250. |

|

| U-250. |

|

| U-250. |

|

| Five of the six survivors in Russian captivity. Center: commander of the submarine, Werner-Karl Schmidt. |

|

| The former commander of the U-250, Werner-Karl Schmidt, is watching the work on his submarine in the Kronstadt dock. |

No comments:

Post a Comment