by Jack Nissen

Among the Allied troops storming ashore in the Dieppe landing on that fateful morning of 19 August 1942 was a young Royal Air Force sergeant, Jack Nissenthall. His mission: to find out how advanced German radar was. A radar expert himself, he knew so much about the British installations that he carried cyanide to take in case he was taken prisoner; as well, the eleven men of the South Saskatchewan Regiment who were his guard had orders to shoot to kill, should he fall into German hands. But in the blood-bath that followed, Sergeant Nissenthall saw all but one of his eleven-man escort die under enemy fire. The survivor, Leslie Thrussell, now lives in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. All these years later, the former sergeant, now Jack Nissen, has an electronics business in Thornhill, Ontario, just north of Toronto, but he’s never forgotten that bitter day.

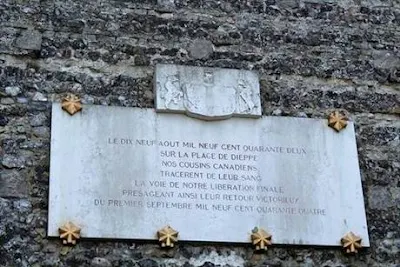

Charlie Sawden, Graham Mavor, Silver Stewart and John Morrison. These are the names of young Canadians who perished on a gloriously sunny day in August 1942. Their average age was twenty-one. They had volunteered for a military operation they were told would bring relief and eventual victory to the hard-pressed Allies in the war against Hitler.

The Second World War was three years old, yet despite the morale-boosting propaganda we had yet to win a decisive battle anywhere. Each month we lost almost a million tons of shipping to German U-boats; food line-ups in Britain became longer and longer, individual rations smaller and smaller.

The Japanese had taken Singapore, Hong Kong, a large portion of China, the Philippines and had invaded India. The Germans were in Moscow’s suburbs and their armies were angling south to the oilfields of the Caucasus and the Middle East. In June, Tobruk had fallen and General Erwin Rommel’s armies had at last entered Egypt. Mussolini prepared to lead the victory parade into Cairo on a beautiful white stallion.

There is little doubt that in mid-1942 the French had every reason to believe the main fighting was over and the Axis powers, Germany, Italy and Japan, had conquered. It was during this period that men of the Canadian 2nd Division prepared for a reconnaissance in force on the northern French port of Dieppe. With no victories to their credit and their military commanders still discredited after the ejection from France at Dunkirk two years earlier, the Allied commanders were striving to set up a new set of military guidelines and disciplines for the hoped-for return to the mainland.

Hitler and propaganda minister Josef Goebbels had boasted of the huge concrete emplacements and massive guns along the French coast to repel invaders. The Wehrmacht, the German Armed Forces, was a highly successful professional; the Allies the apprentices. Nevertheless, we were confronted with the knowledge that the war would never be won until we returned to the continent and defeated the Germans occupying France. It also would have to be done before the battle-hardened German Army returned from the Soviet Union, which in 1942 seemed on the verge of defeat.

A powerful, probing military reconnaissance was required to allow us to verify theories and develop the naval, army, air and communications equipment required when we stormed the German defenses on the return to France. An army of heroes was required—tough troops of high morale to carry out the most hazardous of war operations, a massive commando raid on German-occupied France.

The raid eventually took place on 19 August 1942 and, as is well known, it was a bloody and devastating confrontation. By twelve o’clock that day one thousand Canadians had been killed and more than one thousand others captured. The Royal Air Force lost 105 aircraft, more than twice the number lost in any big battle during the Battle of Britain. Together with the large material losses, the traumatic shock of the disaster rammed home the idiocy of those who insisted the return to the continent would be a “piece of cake.”

Over the years many writers have described the Dieppe raid as utterly useless and a debacle. Every military man knows a reconnaissance or scouting expedition, however small, always yields useful intelligence. On this raid, in which I took part as an agent of the British Air Ministry, we gleaned a storehouse of strategic information which allowed us to set up a whole series of undreamed of military disciplines that are still valid today.

Immediately after the raid, Lord Mountbatten initiated hard-hitting discussions at his headquarters in Richmond Ter-race, Whitehall. Participants in the raid, regardless of rank, were assembled and ordered to criticize every aspect of the operation. From these sessions plans emerged that facilitated the invasion of Normandy.

In the early hours of 6 June 1944, seven thousand vessels took up positions in the storm-swept seas, under the very noses of dozens of superb enemy radars, without a single shot being fired. The silence of the German guns has puzzled writers and historians over the years, for the German radar-controlled guns were known for their deadly accuracy. They could hit a rowboat at ten miles.

Was it really a miracle and sheer good luck that got our armies ashore in exactly the right places and times on that historic occasion? The truth is that the landings were the culmination of two years of top secret hard work, planning, production and subterfuge initiated by Lord Mountbatten immediately after the sessions that followed the Dieppe raid. Naval, army and communications equipment, together with a mass of radar countermeasure devices, were conceived, tested and mass produced for landings that preceded the big target, the Normandy beaches.

When the Canadians landed at Dieppe, they were stymied by a high seawall which ran the length of the beach and which the Churchill tanks could not scale. For the most part, the thirty tanks had to lay back on the water line and exchange fire with entrenched German guns until they were knocked out.

Canadian engineers could not clear the land mines or penetrate the beach defenses because they could not survive under the withering fire of the German gunners in the beachfront hotels. Lord Mountbatten swore that would never happen again.

In 1944 the situation was different: there were hundreds of specialized tanks and aids to invasion that gave us the edge in the first few hours of D-Day.

There were tanks that swam ashore with the troops to ensure that flesh was not pitted against steel. There were armored “flails” which exploded mines in the path of advancing men. There were tanks to lay carpets of coir matting over the sand and shale to avoid the repetition of another Dieppe fiasco, when our tank tracks were wrecked by shale pebbles. Other armored vehicles could toss a huge stack of explosive at a pillbox and demolish it instantly. Churchill tanks, with their superstructures removed, overcame what had been a major obstacle at Dieppe: they would position themselves against a seawall and allow their companions to ride up and over the top. Other tanks had booms to set up temporary bridges which allowed their companions to traverse tank traps and even ride up the base of a cliff. Flamethrower tanks developed at Fort Suffield, Alberta, speeded up the disposal of other strongpoints.

This strange assortment of armored vehicles was developed between Dieppe and D-Day as part of a whole series of aids to invasion that played a large part in the successful landings on the Canadian and British beaches. The Americans, who elected not to use this equipment, suffered a far worse disaster at Omaha Beach on D-Day than had the Canadians at Dieppe. The incredible D-Day naval navigation was not due to normal navigational skill, but the use for the first time of a device developed by and for the RAF. It was a precision air navigational aid known to thousands of Canadian airmen as GEE. Its accuracy was such that a bomber could check its position within fifty yards when 200 miles inside Germany. When used shipboard in the English Channel for sweeping mines and marking the areas, its accuracy was phenomenal. All navigation and position-taking in those dark stormy seas of D-Day were carried out by naval adaptation of the Goon Box, as GEE was affectionately called. Due to its universal use during the invasion, some people feel G-Day would have been more apt than D-Day.

All this wonderful equipment, training and expertise would have been useless if the hundreds of German guns had gone into action on the enormous concentration of ships, some just a mile or two off the coast. A field marshal by then, Rommel made an order that day to the gun crews that had been to the point. “The enemy must be annihilated before he reaches a battlefield. We must stop him in the water, not only delaying him, but by destroying all his equipment while it is still afloat.”

A method had to be found to get the ships close to shore during the darkness without being pulverized by the hundreds of radar-controlled guns. It was the Director-General of Signals and Radar for the RAF, Sir Victor Tait of Winnipeg, who masterminded a plan to dupe the Germans on a once-only basis. It was he who coordinated the ultra-secret stratagems and radar countermeasures.

It was Sir Victor who sent me to Dieppe in 1942 to verify that the Freya radar had become precision radar. Once he had verified this, he ordered the mass production of radar countermeasure equipment. This ultra-secret equipment was codenamed Mandrel. At the throw of a switch, a curtain could be drawn across a Freya radar screen. After some flying tests two months after Dieppe, it was given limited secret service. High-powered Mandrel transmitters were mass produced for installation on two hundred ships for D-Day.

It was Dieppe and the impetus it gave the development of special devices that supplied us the key to victory. Without that 1942 reconnaissance, we would never have developed the systems that enabled us to land safely in Normandy in 1944.

|

| This German map made after the Dieppe Raid shows where the main Canadian forces landed along with the locations of the commando attacks. |

|

| Oblique aerial photograph of Dieppe taken in June, 1945, showing the Red beach. |

|

| This aerial photograph shows the town of Dieppe in 1942 with details added. |

|

| A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment training on a beach near Seaford, Sussex, in July 1942. |

|

| The Casino and the beach as seen on an old postcard. |

|

| The concrete barriers, wire fencing, and other obstacles on the beach show how well the Germans fortified the Dieppe beach. |

|

| A German MG34 medium machine gun emplacement, Dieppe, August 1942. |

|

| Canadian soldiers aboard an LCA (landing craft assault) during a practice prior to the Dieppe raid. |

|

| Personnel of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps in England treating "casualties" during rehearsal in England for raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Canadian troops disembarking from landing craft during training exercise before the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Final training exercise prior to assault landing at Dieppe. |

|

| Final training exercise prior to assault landing at Dieppe. |

|

| A low-level aerial reconnaissance photograph of the Dieppe waterfront taken by the Army Co-operation Command a few days before the raid. |

|

| “Zero Hour”. Sketch by B J Mullen of No. 4 Commando. |

|

| “Through the German Minefield”. Sketch by B J Mullen of No. 4 Commando. |

|

| “Withdraw from Beach”. Sketch by B J Mullen of No. 4 Commando. |

|

| “Rescue of US Airman in Channel”. Sketch by B J Mullen of No. 4 Commando. |

|

| Lieut. Com. J. P. Scatchard (third from left), Lieut. House (first left) on the bridge of HMS Garth. |

|

| HMS Locust. |

|

| A chassure of the type which attempted to enter the harbor at Dieppe. |

|

| Unidentified Hunt Class destroyer of the Royal Navy bombarding Dieppe during Operation Jubilee. |

|

| An Allied naval vessel putting down a smoke screen off the French coast. Behind the smoke screen some of the landing craft are visible. In the foreground are infantry and naval personnel. |

|

| Boston Mark IIIs of No. 88 Squadron RAF tuned up to take part in the Dieppe raid. Serial number Z2216 nearest camera. |

|

| The type of bombs carried by the Boston aircraft taking part in the raid. |

|

| Pilot of one of the Boston aircraft making final notes - pin-pointing his particular objective. |

|

| Air crews of Boston aircraft awaiting their turn to take off on the raid. |

|

| Air crews of Boston aircraft awaiting their turn to take off on the raid. |

|

| Bostons tuned up to take part in the raid. |

|

| Bomb-aimer in the nose of a Boston aircraft taking part in the raid. |

|

| On the way. One of the Bostons taking off for the Dieppe raid. |

|

| A fighter formation taking part in the raid. Aircraft of Fighter Command were an essential "rib" of the "umbrella" which covered the raid from the air. |

|

| Bombs being released from a Douglas Boston bomber over the target area. Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada troops readying to go ashore at Dieppe. |

|

| The last men leaving HMS Berkeley as she settled down in the water after being bombed during the Combined Operations daylight raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Part of the floating reserve at Dieppe. Unarmored landing craft carrying Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal circling off Dieppe previous to landing this unit on the main beaches. |

|

| “Calgary”. |

|

| A Churchill tank from the Calgary Regiment abandoned on the beach. The regiment’s nickname for the tank (“Buttercup”) can be seen on its side. |

|

| Another view of the same wrecked Churchill tank bogged down in the Dieppe sand. |

|

| Another view of the immobilized “Cougar”. |

|

| Another view of “Cat”. |

|

| A “3” is painted on hull side of the beached TLC 3 and “Chief” is flying a command pennant on the turret antenna. Later, a German sailor removed the pennant from the turret as a trophy. |

|

| The ‘Circle F1’ on the turret of this Churchill tank indicate that it is “Chief”. This German soldier is posing next to the tank holding a machete in his right hand. |

|

| A reworked Churchill Mark I ‘F3’ (“Company”) of the Calgary Regiment's "C" Squadron Headquarters knocked out at Dieppe. |

|

| Another view of “Company”. |

|

| This is the left side view of “Company” facing east. Down the beach is TLC 3 No. 159 with “Beetle” to the left of it. Note the pieces of the waterproofing on the turret side. |

|

| This is another view of “Company” with German troops examining the captured tank. Laying on the beach in the foreground is a louver extension from another tank. |

|

| Canadian wounded and abandoned Churchill tanks after the Dieppe Raid. A landing craft is on fire in the background. |

|

| A casualty on the beach at Dieppe by Alfred Hierl. |

|

| German troops examining an abandoned Churchill tank of the Calgary Regiment, left behind during the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Canadian and British dead at Dieppe, August 1942. |

|

| A fallen Canadian soldier lies on the beach with a Daimler scout car and two Churchill tanks in the background. |

|

| Landing craft on fire, Canadian dead in the foreground. A concrete gun emplacement on the right covers the beach; the steep gradient can clearly be seen. |

|

| Abandoned vehicles and landing craft litter the beach. |

|

| Dieppe's chert beach and cliff immediately following the raid on 19 August 1942. A Dingo Scout Car has been abandoned. |

|

| Daimler scout car “Hound” abandoned on the beach. |

|

| Another view of the Daimler scout car “Hector”. |

|

| German soldiers examine Churchill tanks abandoned by Allied soldiers as they were evacuated. Note the Tac signs and the intact exhaust. |

|

| Another view of “Betty”, from the front. |

|

| British and Canadian prisoners resting at Dieppe, August 1942. |

|

| Allied prisoners rest by the roadside, guarded by Germans, Dieppe. |

|

| Canadian soldiers, their backs to the sea wall, await evacuation from the beach. |

|

| Three Canadian soldiers gather around their supplies in the shelter of the sea wall at Dieppe. |

|

| Some of the Canadian troops resting on board a destroyer after the Combined Operations daylight raid on Dieppe. The strain of the operation can be seen on their faces. |

|

| Destroyer ORP Ślązak (Silesian) of the Polish Navy arriving back at Portsmouth from Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| A wounded Canadian soldier being disembarked from the Polish Navy destroyer ORP Ślązak (Silesian) at Portsmouth on return from Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| No. 3 Commando returning to Newhaven after the Dieppe raid. |

|

| Evacuation of wounded soldiers following the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Canadian survivors of the Dieppe Raid, upon their return to England on 19 August 1942. Note the German prisoner at lower right. |

|

| A wounded Canadian soldier being disembarked from the Polish Navy destroyer ORP Ślązak (Silesian) at Portsmouth on return from Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| Back on the dock in England, troops discuss their experiences at Dieppe. |

|

| Soldiers who took part in the raid on Dieppe, returning to England. |

|

| A German prisoner, Unteroffizier Leo Marsiniak, being escorted at Newhaven. He was captured at the gun battery at Varengeville by No. 4 Commando. |

|

| Armed Canadian soldier escorting a German prisoner who was captured during the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Lt Col The Lord Lovat, CO of No. 4 Commando, at Newhaven after returning from the raid. |

|

| British commandos who took part in the raid on Dieppe, returning to England. |

|

| Troops who took part in the raid on Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| Captain J.C.H. Anderson, of the Royal Regiment of Canada, reports what happened on the beach to a Canadian brigadier. |

|

| Crewman with a Douglas Boston aircraft of the Royal Air Force, used in the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Group photo of pilots who took part in the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| In a smoky railway carriage, an American nurse chats to British soldiers who are going on leave after participating in the Allied commando raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Infantrymen of the Essex Scottish Regiment who took part in the raid on Dieppe, after their return to England, 23 August 1942. |

|

| Personnel of the Calgary Regiment who took part in the raid on Dieppe, after their return to England, 23 August 1942. |

|

| Members of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry kneeling at the graves of comrades killed at Dieppe, 1 September 1942. |

|

| Captains E.L. McGivern and J.H. Medhurst examine a German pillbox at Dieppe, 3 September 1944. |

|

| Canadian soldiers marching through liberated Dieppe in September 1944. |

|

| Brig W. Basil Wedd, 1st Canadian Army HQ, placing a wreath on the graves of soldiers killed at Dieppe, 23 September 1944. |

|

| LCol Cecil Merritt, VC, South Saskatchewan Regiment, captured at Dieppe, upon his return to England, 21 April 1945. |

|

| A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment, note the placement of the 3-inch howitzer in the front hull plate. |

|

| A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment, note the Mark I's cast one-piece turret and the absence a mantlet. |

|

| A German soldier watching from a sandbag position on the coast. |

|

| Canadian troops embarking in landing craft during training exercise before the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| A general view of some of the small naval craft covering the landing during the Combined Operations daylight raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Landing craft of the assault troops taking part in Operation Jubilee, Dieppe, 19 August 1942. On the left, a smoke screen produced to conceal them from enemy fire. |

|

| Laying a smoke screen off Dieppe. The smoke screen offered additional protection to the Allied Forces since it helped to conceal their movements from the German forces. |

|

| Fighting in Dieppe. |

|

| Mk.I and Mk.II Churchills and a Bren Gun Carrier on the beach at Dieppe after the raid. “Buttercup” in the middle background. |

|

| In the aftermath of the failed Dieppe Raid, a German soldier stands on the beach watching a British landing craft (TLC 5) burn. |

|

| A reworked Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment's "B" Squadron Headquarters knocked out at Dieppe. |

|

| A reworked Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment's "B" Squadron Headquarters knocked out at Dieppe. |

|

| Another view of Churchill tank "Beetle". |

|

| Another view of “Cat”. |

|

| Canadian casualties litter the Dieppe beach among ruined and abandoned tanks. |

|

| Canadian tanks got bogged down on the pebbled beaches at Dieppe and very few ever made their objective of getting up the cliffs and into the town. |

|

| View looking east along the main beach at Dieppe showing damaged Churchill tanks of the Calgary Regiment. |

|

| Another wrecked Churchill on the beach at Dieppe. |

|

| Churchill tanks and Tank Landing Craft on Dieppe beach. |

|

| A knocked out Churchill Mark II of Regimental Headquarters, The Calgary Regiment at Dieppe. |

|

| Tending to the wounded near a Tank Landing Craft. |

|

| Knocked out vehicles on the Dieppe beach. |

|

| Churchill tank knocked out on Dieppe beach. |

|

| Churchill tank knocked out on Dieppe beach. |

|

| Churchill tank knocked out on Dieppe beach. |

|

| Green Beach after the Dieppe raid. |

|

| Dead Canadians at Dieppe. |

|

| A Landing Craft, Tank grounded on the Dieppe beach. |

|

| An LCT on the beach at Dieppe. |

|

| A Landing Craft Assault on the beach at Dieppe after the raid. |

|

| Canadian dead and a Tank Landing Craft on the Dieppe beach. |

|

| Allied armaments lying just off the beach at Dieppe following the landing onshore. |

|

| An assault craft lying abandoned on the beach following the Dieppe Raid. The photo was taken by German personnel. |

|

| Sunk landing craft on Dieppe beach. |

|

| German soldiers amidst the wreckage and bodies on Dieppe beach. |

|

| The Dieppe Raid was a disaster. A view of the beach from a TLC. |

|

| A mine washed up on the beach at Dieppe. |

|

| Officer and soldiers examining a Churchill tank stuck on the Dieppe beach in front of the boardwalk after the battle, its left track broken. Wounded men lying on the ground are about to be evacuated. |

|

| German troops march Canadian POWs by a destroyed Churchill tank from the Dieppe operation. |

|

| Churchill T68176R “Betty”, one of the few tanks that actually made it up off the beach and into the Dieppe area and was later destroyed. |

|

| Bodies of dead Canadian soldiers near the Dieppe beach. |

|

| A German soldier inspects the damage and destruction along a street in Dieppe following the Allied raid. |

|

| Clearing the beach after the raid. |

|

| Dieppe after the battle. |

|

| Captured Canadian troops on the beach at Dieppe. A knocked out Churchill tank is in the background. |

|

| Canadian POWs, Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| German soldiers amidst the wreckage on Dieppe beach. |

|

| Canadian POWs. |

|

| Canadian and Allied soldiers take care of their own after being taken prisoner during the Dieppe Raid. |

|

| Canadian and Allied soldiers are paraded as prisoners of war by their captors. |

|

| British and Canadian soldiers being taken prisoner after the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| British and Canadian soldiers being taken prisoner after the raid on Dieppe. |

|

| Canadian and British prisoners of war help recover and care for their wounded comrades. |

|

| Canadian and British prisoners of war help recover and care for their wounded comrades. |

|

| Canadian and British prisoners of war help recover and care for their wounded comrades. |

|

| Allied soldiers taken prisoner by the Germans at Dieppe. |

|

| Allied prisoners recover following their assault on the towns of Dieppe, Puys, and Pourville. |

|

| Captured soldiers awaiting transshipment to prisoner of war camps. |

|

| Canadian prisoners escorted by German guards marching through Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| Canadian prisoners of war being led through Dieppe by German soldiers. |

|

| Commandos captured at Dieppe. |

|

| Canadian and Allied POWs at Dieppe. |

|

| The German burial parade. |

|

| Burial of a German casualty though some Canadian casualties were buried here, as well as some quite far away, apparently near German hospitals. |

|

| A wounded soldier is carried off the ship upon his return to England. |

|

| Exhausted but alive, these men are happy to be back in England after nine hours in the Dieppe inferno. |

|

| Jaunty raider who survived Dieppe returns wearing a German helmet as a trophy. His personal weapon is an American Thompson submachine gun. |

|

| Troops who took part in the raid on Dieppe, 19 August 1942. |

|

| Although they understood it as a 'raid', German propaganda portrayed it as an 'invasion catastrophe'. |

|

|

| Lt. Col. C.C. Merritt earned the Victoria Cross for his heroism during the Dieppe Raid; this recruitment poster (1943) uses his bravery as motivation for other men to enlist. |

|

| Advertisement depicting soldiers at Dieppe, published in the October 10, 1942, issue of the Toronto Star Weekly. |

|

| Advertisement for the 3rd Victory Bonds campaign, 1942. |

|

| Advertisement for the 3rd Victory Bonds campaign, 1942. |

|

| Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery, France. |

|

| Dieppe Cemetery, 1965. |

|

| Dieppe Cemetery, 1965. |

|

| LGen Crerar, LGen Simmonds and MGen Faulkes at a ceremony at the Dieppe Cemetery, 1965. |

|

| Canada Square, Dieppe, France. Commemorating the Canadian soldiers who died on the beach of Dieppe on 19 August 1942. |

|

| Memorial and Museum for Operation Jubilee 1942, Dieppe, France, 2008. |

No comments:

Post a Comment