The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, running from 1939 to the defeat of Germany in 1945. At its core was the Allied naval blockade of Germany, announced the day after the declaration of war, and Germany’s subsequent counter-blockade. It was at its height from mid-1940 through to the end of 1943. The Battle of the Atlantic pitted U-boats and other warships of the Kriegsmarine (German navy) and aircraft of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) against the Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Navy, the United States Navy, and Allied merchant shipping. The convoys, coming mainly from North America and predominantly going to the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, were protected for the most part by the British and Canadian navies and air forces. These forces were aided by ships and aircraft of the United States from September 13, 1941. The Germans were joined by submarines of the Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) after their Axis ally Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940.

As an island nation, the United Kingdom was highly dependent on imported goods. Britain required more than a million tons of imported material per week in order to be able to survive and fight. In essence, the Battle of the Atlantic was a tonnage war: the Allied struggle to supply Britain and the Axis attempt to stem the flow of merchant shipping that enabled Britain to keep fighting. From 1942 onwards, the Germans also sought to prevent the build-up of Allied supplies and equipment in the British Isles in preparation for the invasion of occupied Europe. The defeat of the U-boat threat was a pre-requisite for pushing back the Germans, Winston Churchill later wrote,

The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome.

The outcome of the battle was a strategic victory for the Allies—the German blockade failed—but at great cost: 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships were sunk for the loss of 783 U-boats.

The name “Battle of the Atlantic” was coined by Winston Churchill in February 1941. It has been called the “longest, largest, and most complex” naval battle in history. The campaign started immediately after the European war began, and lasted six years. It involved thousands of ships in more than 100 convoy battles and perhaps 1,000 single-ship encounters, in a theatre covering thousands of square miles of ocean. The situation changed constantly, with one side or the other gaining advantage, as new weapons, tactics, counter-measures, and equipment were developed by both sides. The Allies gradually gained the upper hand, overcoming German surface raiders by the end of 1942 and defeating the U-boats by mid-1943, though losses to U-boats continued to war’s end.

On March 5, 1941, First Lord of the Admiralty A.V. Alexander asked Parliament for “many more ships and great numbers of men” to fight “the Battle of the Atlantic,” which he compared to the Battle of France, fought the previous summer. The first meeting of the cabinet’s “Battle of the Atlantic Committee” was on March 19. Churchill claimed to have coined the phrase “Battle of the Atlantic” shortly before Alexander’s speech, but there are several examples of earlier usage.

Following the use of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany in the First World War, countries tried to limit, even abolish, submarines. The effort failed. Instead, the London Naval Treaty required submarines to abide by “cruiser rules,” which demanded they surface, search and place ship crews in “a place of safety” (for which lifeboats did not qualify, except under particular circumstances) before sinking them, unless the ship in question showed “persistent refusal to stop...or active resistance to visit or search.” These regulations did not prohibit arming merchantmen, but doing so, or having them report contact with submarines (or raiders), made them de facto naval auxiliaries and removed the protection of the cruiser rules. This made restrictions on submarines effectively moot.

In 1939, the Kriegsmarine lacked the strength to challenge the combined British Royal Navy and French Navy (Marine Nationale) for command of the sea. Instead, German naval strategy relied on commerce raiding using capital ships, armed merchant cruisers, submarines and aircraft. Many German warships were already at sea when war was declared, including most of the available U-boats and the “pocket battleships” (Panzerschiffe) Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee which had sortied into the Atlantic in August. These ships immediately attacked British and French shipping. U-30 sank the liner SS Athenia within hours of the declaration of war—in breach of her orders not to sink passenger ships. The U-boat fleet, which was to dominate so much of the Battle of the Atlantic, was small at the beginning of the war; many of the 57 available U-boats were the small and short-range Type IIs, useful primarily for minelaying and operations in British coastal waters. Much of the early German anti-shipping activity involved minelaying by destroyers, aircraft and U-boats off British ports.

With the outbreak of war, the British and French immediately began a blockade of Germany, although this had little immediate effect on German industry. The Royal Navy quickly introduced a convoy system for the protection of trade that gradually extended out from the British Isles, eventually reaching as far as Panama, Bombay and Singapore. Convoys allowed the Royal Navy to concentrate its escorts near the one place the U-boats were guaranteed to be found, the convoys. Each convoy consisted of between 30 and 70 mostly unarmed merchant ships.

Some British naval officials, particularly the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, sought a more ‘offensive’ strategy. The Royal Navy formed anti-submarine hunting groups based on aircraft carriers to patrol the shipping lanes in the Western Approaches and hunt for German U-boats. This strategy was deeply flawed because a U-boat, with its tiny silhouette, was always likely to spot the surface warships and submerge long before it was sighted. The carrier aircraft were little help; although they could spot submarines on the surface, at this stage of the war they had no adequate weapons to attack them, and any submarine found by an aircraft was long gone by the time surface warships arrived. The hunting group strategy proved a disaster within days. On September 14, 1939, Britain’s most modern carrier, HMS Ark Royal, narrowly avoided being sunk when three torpedoes from U-39 exploded prematurely. U-39 was forced to surface and scuttle by the escorting destroyers, becoming the first U-boat loss of the war. The British failed to learn the lesson from this encounter: another carrier, HMS Courageous, was sunk three days later by U-29.

Escort destroyers hunting for U-boats continued to be a prominent, but misguided, technique of British anti-submarine strategy for the first year of the war. U-boats nearly always proved elusive, and the convoys, denuded of cover, were put at even greater risk.

German success in sinking Courageous was surpassed a month later when Günther Prien in U-47 penetrated the British base at Scapa Flow and sank the old battleship HMS Royal Oak at anchor, immediately becoming a hero in Germany.

In the South Atlantic, British forces were stretched by the cruise of Admiral Graf Spee, which sank nine merchant ships of 50,000 GRT in the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans during the first three months of war. The British and French formed a series of hunting groups including three battlecruisers, three aircraft carriers, and 15 cruisers to seek the raider and her sister Deutschland, which was operating in the North Atlantic. These hunting groups had no success until Admiral Graf Spee was caught off the mouth of the River Plate by an inferior British force. After suffering damage in the subsequent action, she took shelter in neutral Montevideo harbor and was scuttled on December 17, 1939.

After this initial burst of activity, the Atlantic campaign quieted down. Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander of the U-boat fleet, had planned a maximum submarine effort for the first month of the war, with almost all the available U-boats out on patrol in September. That level of deployment could not be sustained; the boats needed to return to harbor to refuel, re-arm, re-stock supplies, and refit. The harsh winter of 1939–40, which froze over many of the Baltic ports, seriously hampered the German offensive by trapping several new U-boats in the ice. Hitler’s plans to invade Norway and Denmark in the spring of 1940 led to the withdrawal of the fleet’s surface warships and most of the ocean-going U-boats for fleet operations in Operation Weserübung.

The resulting Norwegian campaign revealed serious flaws in the magnetic influence pistol (firing mechanism) of the U-boats’ principal weapon, the torpedo. Although the narrow fjords gave U-boats little room for maneuver, the concentration of British warships, troopships and supply ships provided countless opportunities for the U-boats to attack. Time and again, U-boat captains tracked British targets and fired, only to watch the ships sail on unharmed as the torpedoes exploded prematurely (due to the influence pistol), or hit and failed to explode (because of a faulty contact pistol), or ran beneath the target without exploding (due to the influence feature or depth control not working correctly). Not a single British warship was sunk by a U-boat in more than 20 attacks. As the news spread through the U-boat fleet, it began to undermine morale. The director in charge of torpedo development continued to claim it was the crews’ fault. In early 1941 the problems were determined to be due to differences in the earth’s magnetic fields at high latitudes and a slow leakage of high-pressure air from the submarine into the torpedo’s depth regulation gear. These problems were solved by about March 1941, making the torpedo a formidable weapon.

Early in the war, Dönitz submitted a memorandum to Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the German navy’s Commander-in-Chief, in which he estimated effective submarine warfare could bring Britain to her knees because of her dependence on overseas commerce. He advocated a system known as the Rudeltaktik (the so-called “wolf pack”), in which U-boats would spread out in a long line across the projected course of a convoy. Upon sighting a target, they would come together to attack en masse and overwhelm any escorting warships. While escorts chased individual submarines, the rest of the “pack” would be able to attack the merchant ships with impunity. Dönitz calculated 300 of the latest Atlantic Boats (the Type VII), would create enough havoc among Allied shipping that Britain would be knocked out of the war.

This was in stark contrast to the traditional view of submarine deployment up until then, in which the submarine was seen as a lone ambusher, waiting outside an enemy port to attack ships entering and leaving. This had been a very successful tactic used by British submarines in the Baltic and Bosporus during World War I, but it could not be successful if port approaches were well patrolled. There had also been naval theorists who held submarines should be attached to a fleet and used like destroyers; this had been tried by the Germans at Jutland with poor results, since underwater communications were in their infancy. (Interwar exercises had proven the idea faulty.) The Japanese also adhered to the idea of a fleet submarine, following the doctrine of Mahan, and never used their submarines either for close blockade or convoy interdiction. The submarine was still looked upon by much of the naval world as “dishonorable,” compared to the prestige attached to capital ships. This was true in Kriegsmarine as well; Raeder successfully lobbied for the money to be spent on capital ships instead.

The Royal Navy’s main anti-submarine weapon before the war was the inshore patrol craft, which was fitted with hydrophones and armed with a small gun and depth charges. The Royal Navy, like most, had not considered anti-submarine warfare as a tactical subject during the 1920s and 1930s. Unrestricted submarine warfare had been outlawed by the London Naval Treaty; anti-submarine warfare was seen as ‘defensive’ rather than dashing; many naval officers believed anti-submarine work was drudgery similar to mine sweeping; and ASDIC was believed to have rendered submarines impotent. Although destroyers also carried depth charges, it was expected these ships would be used in fleet actions rather than coastal patrol, so they were not extensively trained in their use. The British, however, ignored the fact that arming merchantmen, as Britain did from the start of the war, removed them from the protection of the “cruiser rules,” and the fact that anti-submarine trials with ASDIC had been conducted in ideal conditions.

The German occupation of Norway in April 1940, the rapid conquest of the Low Countries and France in May and June and the Italian entry into the war on the Axis side in June transformed the war at sea in general and the Atlantic campaign in particular in three main ways:

Britain lost her biggest ally. In 1940, the French Navy was the fourth largest in the world. Only a handful of French ships joined the Free French Forces and fought against Germany, though these were later joined by a few Canadian-built corvettes. With the French fleet removed from the campaign, the Royal Navy was stretched even further. Italy’s declaration of war meant that Britain also had to reinforce her Mediterranean Fleet and establish a new group at Gibraltar, known as Force H, to replace the French fleet in the Western Mediterranean.

The U-boats gained direct access to the Atlantic. Since the English Channel was relatively shallow, and was partially blocked with minefields by mid-1940, U-boats were ordered not to negotiate it and instead travel around the British Isles to reach the most profitable hunting grounds. The German bases in France, at Brest, Lorient, La Pallice (near La Rochelle), were about 450 miles (720 km) closer to the Atlantic than the bases on the North Sea. This greatly improved the situation for U-boats in the Atlantic, enabling them to attack convoys further west and letting them spend longer time on patrol, doubling the effective size of the U-boat force. The Germans later built huge fortified concrete submarine pens for the U-boats in the French Atlantic bases, which were impervious to Allied bombing until the Tallboy bomb was developed. From early July, U-boats returned to the new French bases when they had completed their Atlantic patrols.

British destroyers were diverted from the Atlantic. The Norwegian Campaign and the German invasion of the Low Countries and France imposed a heavy strain on the Royal Navy’s destroyer flotillas. Many older destroyers were withdrawn from convoy routes to support the Norwegian campaign in April and May and then diverted to the English Channel to support the withdrawal from Dunkirk. By the summer of 1940, Britain faced a serious threat of invasion. Many destroyers were held in the Channel, ready to repel a German invasion. They suffered heavily under air attack by the Luftwaffe’s Fliegerführer Atlantik. Seven destroyers were lost in the Norwegian campaign, another six in the Battle of Dunkirk and a further 10 in the Channel and North Sea between May and July, many to air attack because they lacked an adequate anti-aircraft armament. Dozens of others were damaged.

The completion of Hitler’s campaign in Western Europe meant U-boats withdrawn from the Atlantic for the Norwegian campaign now returned to the war on trade. So at the very time the number of U-boats on patrol in the Atlantic began to increase, the number of escorts available for the convoys was greatly reduced. The only consolation for the British was that the large merchant fleets of occupied countries like Norway and the Netherlands came under British control. After the German occupation of Denmark and Norway, Britain occupied Iceland and the Faroe Islands, establishing bases there and preventing a German takeover.

It was in these circumstances that Winston Churchill, who had become Prime Minister on May 10, 1940, first wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt to request the loan of fifty obsolescent U.S. Navy destroyers. This eventually led to the “Destroyers for Bases Agreement” (effectively a sale but portrayed as a loan for political reasons), which operated in exchange for 99-year leases on certain British bases in Newfoundland, Bermuda and the West Indies, a financially advantageous bargain for the United States but militarily beneficial for Britain, since it effectively freed up British military assets to return to Europe. A significant percentage of the U.S. population opposed entering the war, and some American politicians (including the U.S. Ambassador to Britain, Joseph P. Kennedy) considered Britain and her allies might actually lose. The first of these destroyers were only taken over by their British and Canadian crews in September and all needed to be rearmed and fitted with ASDIC. It was to be many months before these ships contributed to the campaign.

The early U-boat operations from the French bases were spectacularly successful. This was the heyday of the great U-boat aces like Günther Prien of U-47, Otto Kretschmer (U-99), Joachim Schepke (U-100), Engelbert Endrass (U-46), Victor Oehrn (U-37) and Heinrich Bleichrodt (U-48). U-boat crews became heroes in Germany. From June until October 1940, over 270 Allied ships were sunk: this period was referred to by U-boat crews as “the Happy Time” (“Die Glückliche Zeit”). Churchill would later write: ...”the only thing that ever frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

The biggest challenge for the U-boats was to find the convoys in the vastness of the ocean. The Germans had a handful of very long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor aircraft based at Bordeaux and Stavanger which were used for reconnaissance. The Condor being a converted civilian airliner, this was a stop-gap solution for Fliegerführer Atlantik. Due to ongoing friction between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine, the primary source of convoy sightings was the U-boats themselves. Since a submarine’s bridge was very close to the water, their range of visual detection was quite limited. The best source proved to be the codebreakers of B-Dienst.

In response, the British applied the techniques of operations research to the problem and came up with some counter-intuitive solutions to the problem of protecting convoys. It was realized the area of a convoy increased by the square of its perimeter, meaning the same number of ships, using the same number of escorts, was better protected in one convoy than in two. A large convoy was as difficult to locate as a small one. Moreover, reduced frequency (fewer large convoys carry the same cargo, and large convoys take longer to assemble) also reduced the chances of detection. Therefore, a few large convoys with apparently few escorts were safer than many small convoys with a higher ratio of escorts to merchantmen.

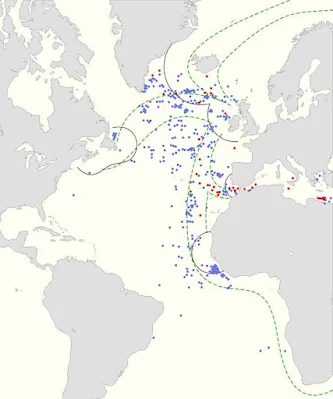

Instead of attacking the Allied convoys singly, U-boats were directed to work in wolf packs (Rudel) coordinated by radio. German codebreaking efforts at B-Dienst had succeeded in deciphering the British Naval Cypher No. 3, allowing the Germans to estimate where and when convoys could be expected. The boats spread out into a long patrol line that bisected the path of the Allied convoy routes. Once in position, the crew studied the horizon through binoculars looking for masts or smoke, or used hydrophones to pick up propeller noises. When one boat sighted a convoy, it would report the sighting to U-boat headquarters, shadowing and continuing to report as needed until other boats arrived, typically at night. Instead of being faced by single submarines, the convoy escorts then had to cope with groups of up to half a dozen U-boats attacking simultaneously. The most daring commanders, such as Kretschmer, penetrated the escort screen and attacked from within the columns of merchantmen. The escort vessels, which were too few in number and often lacking in endurance, had no answer to multiple submarines attacking on the surface at night as their ASDIC only worked well against underwater targets. Early British marine radar, working in the metric bands, lacked target discrimination and range. Moreover, corvettes were too slow to catch a surfaced U-boat.

Pack tactics were first used successfully in September and October 1940, to devastating effect, in a series of convoy battles. On September 21, convoy HX 72 of 42 merchantmen was attacked by a pack of four U-boats, losing eleven ships sunk and two damaged over two nights. In October, the slow convoy SC 7, with an escort of two sloops and two corvettes, was overwhelmed, losing 59% of its ships. The battle for HX 79 in the following days was in many ways worse for the escorts than for SC 7. The loss of a quarter of the convoy without any loss to the U-boats, despite very strong escort (two destroyers, four corvettes, three trawlers, and a minesweeper) demonstrated the effectiveness of the German tactics against the inadequate British anti-submarine methods. On December 1, seven German and three Italian submarines caught HX 90, sinking 10 ships and damaging three others. The success of pack tactics against these convoys encouraged Admiral Dönitz to adopt the wolf pack as his primary tactic.

Nor were the U-boats the only threat. Following some early experience in support of the war at sea during Operation Weserübung, Fliegerführer Atlantik contributed small numbers of aircraft to the Battle of the Atlantic from 1940 onwards. These were primarily Fw 200 Condors and (later) Junkers Ju 290s, used for long-range reconnaissance. The Condors also bombed convoys that were beyond land-based fighter cover and thus defenseless. Initially, the Condors were very successful, claiming 365,000 tons of shipping in early 1941. These aircraft were few in number, however, and directly under Luftwaffe control; in addition, the pilots had little specialized training for anti-shipping warfare, limiting their effectiveness.

The Germans received help from their allies. From August 1940, a flotilla of 27 Italian submarines operated from the BETASOM base in Bordeaux to attack Allied shipping in the Atlantic, initially under the command of Rear Admiral Angelo Parona, then of Rear Admiral Romolo Polacchini. The Italian submarines had been designed to operate in a different way than U-Boote, and they had a number of flaws that needed to be corrected (for example huge conning towers, slow speed when surfaced, lack of modern torpedo fire control), which meant that they were ill suited for convoy attacks, and performed better when hunting down isolated merchantmen on distant seas, taking advantage of their superior range and living standards. While initial operation met with little success (only 65,343 GRT sunk between August and December 1940), the situation improved gradually over time, and up to August 1943 the 32 Italian submarines that operated there sank 109 ships of 593,864 tons, for 17 subs lost in return, giving them a subs-lost-to-tonnage sunk ratio similar to Germany’s in the same period, and higher overall. The Italians were also successful with their use of “human torpedo” chariots, disabling several British ships in Gibraltar.

Despite these successes, the Italian intervention was not favorably regarded by Dönitz, who characterized Italians as “inadequately disciplined” and “unable to remain calm in the face of the enemy.” They were unable to cooperate in wolf pack tactics or even reliably report contacts or weather conditions and their area of operation was moved away from those of the Germans.

Amongst the more successful Italian submarine commanders that operated in the Atlantic were Carlo Fecia di Cossato, commander of the submarine Tazzoli, and Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia, commander of the Archimede and then of the Leonardo da Vinci.

ASDIC (also known as SONAR) was a central feature of the Battle of the Atlantic. One crucial development was the integration of ASDIC with a plotting table and weapons (depth charges and later Hedgehog) to make an anti-submarine warfare system.

ASDIC produced an accurate range and bearing to the target, but could be fooled by thermoclines, currents or eddies, and schools of fish, so it needed experienced operators to be effective. ASDIC was effective only at low speeds. Above 15 knots (28 km/h) or so, the noise of the ship going through the water drowned out the echoes.

The early wartime Royal Navy procedure was to sweep the ASDIC in an arc from one side of the escort’s course to the other, stopping the transducer every few degrees to send out a signal. Several ships searching together would be used in a line, 1–1.5 mi (1.6–2.4 km) apart. If an echo was detected, and if the operator identified it as a submarine, the escort would be pointed towards the target and would close at a moderate speed; the submarine’s range and bearing would be plotted over time to determine course and speed as the attacker closed to within 1,000 yards (910 m). Once it was decided to attack, the escort would increase speed, using the target’s course and speed data to adjust her own course. The intention was to pass over the submarine, rolling depth charges from chutes at the stern at even intervals, while throwers fired further charges some 40 yd (37 m) to either side. The intention was to lay a ‘pattern’ like an elongated diamond, hopefully with the submarine somewhere inside it. To effectively disable a submarine, a depth charge had to explode within about 20 ft (6.1 m). Since early ASDIC equipment was poor at determining depth, it was usual to vary the depth settings on part of the pattern.

There were disadvantages to the early versions of this system. Exercises in anti-submarine warfare had been restricted to one or two destroyers hunting a single submarine whose starting position was known, and working in daylight and calm weather. U-boats could dive far deeper than British or American submarines (over 700 feet (210 m)), well below the 350-foot (110 m) maximum depth charge setting of British depth charges. More importantly, early ASDIC sets could not look directly down, so the operator lost contact on the U-boat during the final stages of the attack, a time when the submarine would certainly be maneuvering rapidly. The explosion of a depth charge also disturbed the water, so ASDIC contact was very difficult to regain if the first attack had failed. It enabled the U-boat to change position with impunity.

The belief ASDIC had solved the submarine problem, the acute budgetary pressures of the Great Depression, and the pressing demands for many other types of rearmament meant little was spent on anti-submarine ships or weapons. Most British naval spending, and many of the best officers, went into the battlefleet. Critically, the British expected, as in the First World War, German submarines would be coastal craft and only threaten harbor approaches. As a result, the Royal Navy entered the Second World War in 1939 without enough long-range escorts to protect ocean-going shipping, and there were no officers with experience of long-range anti-submarine warfare. The situation in Royal Air Force Coastal Command was even more dire: patrol aircraft lacked the range to cover the North Atlantic and could typically only machine-gun the spot where they saw a submarine dive.

Despite their success, U-boats were still not recognized as the foremost threat to the North Atlantic convoys. With the exception of men like Dönitz, most naval officers on both sides regarded surface warships as the ultimate commerce destroyers.

For the first half of 1940, there were no German surface raiders in the Atlantic because the German Fleet had been concentrated for the invasion of Norway. The sole pocket battleship raider, Admiral Graf Spee, had been stopped at the Battle of the River Plate by an inferior and outgunned British squadron. From the summer of 1940 a small but steady stream of warships and armed merchant raiders set sail from Germany for the Atlantic.

The power of a raider against a convoy was demonstrated by the fate of convoy HX 84 attacked by the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer on November 5, 1940. Admiral Scheer quickly sank five ships and damaged several others as the convoy scattered. Only the sacrifice of the escorting Armed Merchant Cruiser HMS Jervis Bay and failing light allowed the other merchantmen to escape. The British now suspended North Atlantic convoys and the Home Fleet put to sea to try to intercept Admiral Scheer. The search failed and Admiral Scheer disappeared into the South Atlantic. She reappeared in the Indian Ocean the following month.

Other German surface raiders now began to make their presence felt. On Christmas Day 1940, the cruiser Admiral Hipper attacked the troop convoy WS 5A, but was driven off by the escorting cruisers. Hipper had more success two months later, on February 12, 1941, when she found the unescorted convoy SLS 64 of 19 ships and sank seven of them. In January 1941, the formidable (and fast) battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which outgunned any Allied ship that could catch them, put to sea from Germany to raid the shipping lanes in Operation Berlin. With so many German raiders at large in the Atlantic, the British were forced to provide battleship escorts to as many convoys as possible. This twice saved convoys from slaughter by the German battleships. In February, the old battleship HMS Ramillies deterred an attack on HX 106. A month later, SL 67 was saved by the presence of HMS Malaya.

In May, the Germans mounted the most ambitious raid of all: Operation Rheinübung. The new battleship Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen put to sea to attack convoys. A British fleet intercepted the raiders off Iceland. In the Battle of the Denmark Strait, the battlecruiser HMS Hood was blown up and sunk, but Bismarck was damaged and had to run to France. Bismarck nearly reached her destination, but was disabled by an airstrike from the carrier HMS Ark Royal, and then sunk by the Home Fleet three days later. Her sinking marked the end of the warship raids. The advent of long-range search aircraft, notably the unglamorous but versatile PBY Catalina, largely neutralized surface raiders.

In February 1942, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen moved from Brest back to Germany in the “Channel Dash.” While this was an embarrassment for the British, it was the end of the German surface threat in the Atlantic. The loss of Bismarck, Arctic convoys, and the perceived invasion threat to Norway had persuaded Hitler to withdraw.

War had come too early for the German naval expansion project Plan Z. Battleships powerful enough to destroy any convoy escort, with escorts able to annihilate the convoy, were never achieved. Although the number of ships the raiders sank was relatively small compared with the losses to U-boats, mines, and aircraft, their raids severely disrupted the Allied convoy system, reduced British imports, and strained the Home Fleet.

The disastrous convoy battles of October 1940 forced a change in British tactics. The most important of these was the introduction of permanent escort groups to improve the co-ordination and effectiveness of ships and men in battle. British efforts were helped by a gradual increase in the number of escort vessels available as the old ex-American destroyers and the new British- and Canadian-built Flower-class corvettes were now coming into service in numbers. Many of these ships became part of the huge expansion of the Royal Canadian Navy, which grew from a handful of destroyers at the outbreak of war to take an increasing share of convoy escort duty. Others of the new ships were manned by Free French, Norwegian and Dutch crews, but these were a tiny minority of the total number, and directly under British command. By 1941 American public opinion had begun to swing against Germany, but the war was still essentially Great Britain and the Empire against Germany.

Initially, the new escort groups consisted of two or three destroyers and half a dozen corvettes. Since two or three of the group would usually be in dock repairing weather or battle damage, the groups typically sailed with about six ships. The training of the escorts also improved as the realities of the battle became obvious. A new base was set up at Tobermory in the Hebrides to prepare the new escort ships and their crews for the demands of battle under the strict regime of Vice-Admiral Gilbert O. Stephenson.

In February 1941, the Admiralty moved the headquarters of Western Approaches Command from Plymouth to Liverpool, where much closer contact with, and control of, the Atlantic convoys was possible. Greater co-operation with supporting aircraft was also achieved. In April, the Admiralty took over operational control of Coastal Command aircraft. At a tactical level, new short-wave radar sets that could detect surfaced U-boats and were suitable for both small ships and aircraft began to arrive during 1941.

The impact of these changes first began to be felt in the battles during the spring of 1941. In early March, Prien in U-47 failed to return from patrol. Two weeks later, in the battle of Convoy HX 112, the newly formed 3rd Escort Group of five destroyers and two corvettes held off the U-boat pack. U-100 was detected by the primitive radar on the destroyer HMS Vanoc, rammed and sunk. Shortly afterwards the U-99 was also caught and sunk, its crew captured. Dönitz had lost his three leading aces: Kretschmer, Prien, and Schepke.

Dönitz now moved his wolf packs further west, in order to catch the convoys before the anti-submarine escort joined. This new strategy was rewarded at the beginning of April when the pack found Convoy SC 26 before its anti-submarine escort had joined. Ten ships were sunk, but another U-boat was lost.

In June 1941, the British decided to provide convoy escort for the full length of the North Atlantic crossing. To this end, the Admiralty asked the Royal Canadian Navy on May 23, to assume the responsibility for protecting convoys in the western zone and to establish the base for its escort force at St. John’s, Newfoundland. On June 13, 1941 Commodore Leonard Murray, Royal Canadian Navy, assumed his post as Commodore Commanding Newfoundland Escort Force, under the overall authority of the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches, at Liverpool. Six Canadian destroyers and 17 corvettes, reinforced by seven destroyers, three sloops, and five corvettes of the Royal Navy, were assembled for duty in the force, which escorted the convoys from Canadian ports to Newfoundland and then on to a meeting point south of Iceland, where the British escort groups took over.

By 1941, the United States was taking an increasing part in the war, despite its nominal neutrality. In April 1941 President Roosevelt extended the Pan-American Security Zone east almost as far as Iceland. British forces occupied Iceland when Denmark fell to the Germans in 1940; the U.S. was persuaded to provide forces to relieve British troops on the island. American warships began escorting Allied convoys in the western Atlantic as far as Iceland, and had several hostile encounters with U-boats. A Mid-Ocean Escort Force of British, and Canadian, and American destroyers and corvettes was organized following the declaration of war by the United States.

In June 1941, the U.S. realized the tropical Atlantic had become dangerous for unescorted American as well as British ships. On May 21, the SS Robin Moor, an American vessel carrying no military supplies, was stopped by U-69 750 miles (1,210 km) west of Freetown, Sierra Leone. After its passengers and crew were allowed thirty minutes to board lifeboats, U-69 torpedoed, shelled, and sank the ship. The survivors then drifted without rescue or detection for up to eighteen days. When news of the sinking reached the U.S., few shipping companies felt truly safe anywhere. As Time magazine noted in June 1941, “if such sinkings continue, U.S. ships bound for other places remote from fighting fronts, will be in danger. Henceforth the U.S. would either have to recall its ships from the ocean or enforce its right to the free use of the seas.”

At the same time, the British were working on a number of technical developments which would address the German submarine superiority. Though these were British inventions, the critical technologies were provided freely to the U.S., which then renamed and manufactured them. In many cases this has resulted in the misconception these were American developments. Likewise, the U.S. provided the British with technology, including Catalina flying boats and Liberator bombers, that were important contributions to the war effort.

Aircraft ranges were constantly improving, but the Atlantic was far too large to be covered completely by land-based types. A stop-gap measure was instituted by fitting ramps to the front of some of the cargo ships known as Catapult Aircraft Merchantmen (CAM ships), equipped with a lone expendable Hurricane fighter aircraft. When a German bomber approached, the fighter was fired off the end of the ramp with a large rocket to shoot down or drive off the German aircraft, the pilot then ditching in the water and (hopefully) being picked up by one of the escort ships if land was too far away. Nine combat launches were made, resulting in the destruction of eight Axis aircraft for the loss of one Allied pilot.

Although the results gained by the CAM ships and their Hurricanes were not great in enemy aircraft shot down, the aircraft shot down were mostly Fw 200 Condors that would often shadow the convoy out of range of the convoy’s guns, reporting back the convoy’s course and position so that U-boats could then be directed on to the convoy. The CAM ships and their Hurricanes thus justified the cost in fewer ship losses overall.

One of the more important developments was ship-borne direction-finding radio equipment, known as HF/DF (high-frequency direction-finding, or Huff-Duff), which was gradually fitted to the larger escorts. HF/DF let an operator determine the direction of a radio signal, regardless of whether the content could be read. Since the wolf pack relied on U-boats reporting convoy positions by radio, there was a steady stream of messages to intercept. A destroyer could then run in the direction of the signal and attack the U-boat, or at least force it to submerge (causing it to lose contact), which might prevent an attack on the convoy. When two ships fitted with HF/DF accompanied a convoy, a fix on the transmitter’s position, not just direction, could be determined. The British also made extensive use of shore HF/DF stations, to keep convoys updated with positions of U-boats.

The radio technology behind HF/DF was simple and well understood by both sides, but the technology commonly used before the war used a manually-rotated aerial to fix the direction of the transmitter. This was delicate work, took quite a time to accomplish to any degree of accuracy, and since it only revealed the line along which the transmission originated a single set could not determine if the transmission was from the true direction or its reciprocal 180 degrees in the opposite direction. Two sets were required to fix the position. Believing this to still be the case, German U-boat radio operators considered themselves fairly safe if they kept messages short. The British, however, developed an oscilloscope-based indicator which instantly fixed the position the moment a radio operator touched his Morse key. It worked simply with a crossed pair of conventional and fixed directional aerials, the oscilloscope display showing the relative received strength from each aerial as an elongated ellipse showing the line relative to the ship. The innovation was a ‘sense’ aerial which when switched in, suppressed the ellipse in the ‘wrong’ direction leaving only the correct bearing. With this there was hardly any need to triangulate—the escort could just run down the precise bearing provided and use radar for final positioning. Many U-boat attacks were suppressed and submarines sunk in this way—a good example of the great difference apparently minor aspects of technology could make to the battle.

The way Dönitz conducted the U-boat campaign required relatively large volumes of traffic between U-boats and headquarters. This was thought to be safe as the radio messages were enciphered using the Enigma cipher machine, which the Germans considered unbreakable. In addition, the Kriegsmarine used much more secure operating procedures than the Heer (army) or Luftwaffe (air force). The machine’s three rotors were chosen from a set of eight (rather than the other services’ five). The rotors and their settings were changed every other day using a system of key sheets and “bigram tables” that were issued to operators. In 1939, it was generally believed at the British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park that naval Enigma could not be broken. Only the head of the German Naval Section, Frank Birch, and the mathematician Alan Turing believed otherwise.

The British codebreakers needed to know the wiring of the special naval Enigma rotors, and the destruction of U-33 by HMS Gleaner in February 1940 provided this information. In early 1941, the Royal Navy made a concerted effort to assist the codebreakers, and on May 9 crew members of the destroyer Bulldog boarded U-110 and recovered her cryptologic material, including bigram tables and current Enigma keys. The captured material allowed all U-boat traffic to be read for several weeks, until the keys ran out; the familiarity codebreakers gained with the usual content of messages helped in breaking new keys.

Throughout the summer and autumn of 1941, Enigma intercepts (combined with HF/DF) enabled the British to plot the positions of U-boat patrol lines and route convoys around them. Merchant ship losses dropped by over two-thirds in July 1941, and the losses remained low until November.

This Allied advantage was offset by the growing numbers of U-boats coming into service. The Type VIIC began reaching the Atlantic in large numbers in 1941; by the end of 1945, 568 had been commissioned. Although the Allies could protect their convoys in late 1941, they were not sinking many U-boats. The Flower-class corvette escorts could detect and defend, but they were not fast enough to attack effectively.

In October 1941, Hitler ordered Dönitz to move U-boats into the Mediterranean to support German operations in that theatre. The resulting concentration near Gibraltar resulted in a series of battles around the Gibraltar and Sierra Leone convoys. In December 1941, Convoy HG 76 sailed, escorted by the 36th Escort Group of two sloops and six corvettes under Captain Frederic John Walker, reinforced by the first of the new escort carriers, HMS Audacity, and three destroyers from Gibraltar. The convoy was immediately intercepted by the waiting U-boat pack, resulting in a brutal battle. Walker was a tactical innovator, his ships’ crews were highly trained and the presence of an escort carrier meant U-boats were frequently sighted and forced to dive before they could get close to the convoy. Over the next five days, five U-boats were sunk (four by Walker’s group), despite the loss of Audacity after two days. The British lost Audacity, a destroyer and only two merchant ships. The battle was the first clear Allied convoy victory.

Through dogged effort, the Allies slowly gained the upper hand until the end of 1941. Although Allied warships failed to sink U-boats in large numbers, most convoys evaded attack completely. Shipping losses were high, but manageable.

The attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent German declaration of war on the United States had an immediate effect on the campaign. Dönitz promptly planned to attack shipping off the American East Coast. He had only 12 Type IX boats able to reach U.S. waters; half of them had been diverted by Hitler to the Mediterranean. One of the remainder was under repair, leaving only five boats for Operation Drumbeat (Paukenschlag), sometimes called by the Germans the “Second happy time.”

The U.S., having no direct experience of modern naval war on its own shores, did not employ a black-out. U-boats simply stood off shore at night and picked out ships silhouetted against city lights. Admiral Ernest King, Commander-in-Chief United States Fleet (Cominch), who disliked the British, initially rejected Royal Navy calls for a coastal black-out or convoy system. King has been criticized for this decision, but his defenders argue the United States destroyer fleet was limited (partly because of the sale of 50 old destroyers to Britain earlier in the war), and King claimed it was far more important that destroyers protect Allied troop transports than merchant shipping. His ships were also busy convoying Lend-Lease material to the Soviet Union, as well as fighting the Japanese in the Pacific. This does not explain the refusal to require coastal black-outs, or to respond to any advice the Royal Navy (or Royal Canadian Navy) provided. No troop transports were lost, but merchant ships sailing in U.S. waters were left exposed and suffered accordingly. Britain eventually had to build coastal escorts and provide them to the U.S. in a “reverse Lend Lease,” since King was unable (or unwilling) to make any provision himself.

The first U-boats reached U.S. waters on January 13, 1942. By the time they withdrew on February 6, they had sunk 156,939 tons of shipping without loss. The first batch of Type IXs was followed by more Type IXs and Type VIIs supported by Type XIV “Milk Cow” tankers which provided refueling at sea. They sank 397 ships totaling over 2 million tons. (As mentioned previously, not a single troop transport was lost.) In 1943, the United States launched over 11 million tons of merchant shipping; that number declined in the later war years, as priorities moved elsewhere.

In May, King (by this time both Cominch and CNO) finally scraped together enough ships to institute a convoy system. This quickly led to the loss of seven U-boats. The U.S. did not have enough ships to cover all the gaps; the U-boats continued to operate freely during the Battle of the Caribbean and throughout the Gulf of Mexico (where they effectively closed several U.S. ports) until July, when the British-loaned escorts began arriving. These included 24 armed anti-submarine trawlers crewed by the Royal Naval Patrol Service; many had previously been peace-time fishermen. On July 3, 1942, one of these trawlers, HMS Le Tigre proved her worth by picking up 31 survivors from the American merchant Alexander Macomb. Shortly after Le Tigre managed to hunt down the U-boat U-215 that had torpedoed the merchant ship, which was then sunk by HMS Veteran; credit was awarded to Le Tigre. The institution of an interlocking convoy system on the American coast and in the Caribbean Sea in mid-1942 resulted in an immediate drop in attacks in those areas. As a result of the increased coastal convoy escort system, the U-boats’ attention was shifted back to the Atlantic convoys. For the Allies, the situation was serious but not critical throughout much of 1942.

Operation Drumbeat had one other effect. It was so successful that Dönitz’s policy of economic war was seen, even by Hitler, as the only effective use of the U-boat; he was given complete freedom to use them as he saw fit. Meanwhile, Hitler sacked Raeder after the embarrassing Battle of the Barents Sea, in which two German heavy cruisers were beaten off by half a dozen British destroyers. Dönitz was eventually made Grand Admiral, and all building priorities turned to U-boats.

With the U.S. finally arranging convoys, ship losses to the U-boats quickly dropped, Dönitz realized his U-boats were better used elsewhere. On July 19, 1942, he ordered the last boats to withdraw from the United States Atlantic coast; by the end of July 1942 he had shifted his attention back to the North Atlantic. Convoy SC 94 marked the return of the U-boats to the convoys from Canada to Britain.

There were enough U-boats spread across the Atlantic to allow several wolf packs to attack many different convoy routes. Often as many as 10 to 15 boats would attack in one or two waves, following convoys like SC 104 and SC 107 by day and attacking at night. Convoy losses quickly increased and in October 1942, 56 ships of over 258,000 tons were sunk in the “air gap” between Greenland and Iceland.

U-boat losses also climbed. In the first six months of 1942, 21 were lost, less than one for every 40 merchant ships sunk. In August and September, 60 were sunk, one for every 10 merchant ships, almost as many as in the previous two years.

On November 19, 1942, Admiral Noble was replaced as Commander-in-Chief of Western Approaches Command by Admiral Sir Max Horton. Horton used the growing number of escorts becoming available to organize “support groups,” to reinforce convoys that came under attack. Unlike the regular escort groups, support groups were not directly responsible for the safety of any particular convoy. This gave them much greater tactical flexibility, allowing them to detach ships to hunt submarines spotted by reconnaissance or picked up by HF/DF. Where regular escorts would have to break off and stay with their convoy, the support group ships could keep hunting a U-boat for many hours. One tactic introduced by Captain John Walker was the “hold-down,” where a group of ships would patrol over a submerged U-boat until its air ran out and it was forced to the surface; this might take two or three days.

In response to the ineffectiveness of depth charges, the British developed ahead-throwing anti-submarine weapons, starting with Hedgehog.

By late 1942, warships started being fitted with the Hedgehog anti-submarine spigot mortar, which fired contact-fuzed bombs ahead of the firing ship while the target was still within the ASDIC beam. Unlike depth charges, which were launched behind and to the sides of the attacking ship and disturbed the water, making it hard to track the target because ASDIC lost contact, Hedgehog charges exploded on impact. Hedgehog allowed the attacking ship to change course and maintain contact as the target maneuvered, as well as allowing a normal depth charge attack.

Hedgehog solved one of the most pressing problems, keeping ASDIC contact at short ranges. As range shortened, so did the time taken for the sound pulse to reach, and then return from, the target. Eventually, the ASDIC operator received an echo almost simultaneously with the emitted pulse, a so-called ‘instantaneous echo,’ making target tracking difficult. Hedgehog allowed the target to be attacked while within the usable range of the ASDIC equipment.

Squid was an improvement on ‘Hedgehog’ introduced in late 1943. A three-barreled mortar, it projected 100 lb (45 kg) charges ahead or abeam; the charges’ firing pistols were automatically set just prior to launch.

Ahead-throwing weapons including Hedgehog and Squid raised the percentage of kills by British surface ships (1943–45) from 85 kills in 5,174 attacks (1.6%) for depth charges to 47 in 268 attacks (17.5%) for Hedgehog, the success rates rising with time.

Detection by radar-equipped aircraft could suppress U-boat activity over a wide area, but an aircraft attack would only be successful with good visibility. U-boats were relatively safe from aircraft at night, since radar then in use could not detect at close range and the deployment of an illuminating flare gave warning of the attack. The introduction by the British of the Leigh Light in June 1942 was a significant factor in the North Atlantic struggle. It was a powerful searchlight that was automatically aligned with the radar to illuminate targets suddenly while in the final stages of an attack run. This enabled British aircraft to attack U-boats recharging batteries on the surface at night, forcing German submarine skippers to switch to daytime recharges.

U-boat commanders who survived such attacks reported a particular fear of this weapon system since aircraft could not be seen at night, and the noise of an approaching aircraft was inaudible above the din made by the boat. The aircraft made contact with the submarine using centimetric radar, which was undetectable with typical U-boat equipment, then lined up on an attack run (the set would automatically reduce power during the approach making detection more difficult). With a mile or so to go the searchlight would automatically switch on, immediately and accurately illuminating the target from the sky, giving less than 10 seconds warning before it was attacked with a stick of bombs. A drop in Allied shipping losses from 600,000 to 200,000 tons per month was attributed to this device.

By August 1942 U-boats were being fitted with radar detectors to enable them to avoid sudden ambushes by radar-equipped aircraft or ships. The first such receiver, named Metox after its French manufacturer, was capable of picking up the metric radar bands used by the early radars. This not only enabled U-boats to avoid detection by Canadian escorts, which were equipped with obsolete radar sets, but allowed them to track convoys where these sets were in use.

However, it also caused problems for the Germans, as it sometimes detected stray radar emissions from distant ships or planes, causing U-boats to submerge when they were not in actual danger, preventing them from recharging batteries or using their surfaced speed.

Metox provided the U-boat commander with an advantage that had not been anticipated by the British. The Metox set beeped at the pulse rate of the hunting aircraft’s radar, approximately once per second. When the radar operator came within 9 miles of the U-boat, he changed the range of his radar. With the change of range, the radar doubled its pulse repetition frequency and as a result, the Metox beeping frequency also doubled warning the commander that he had been detected.

On February 1, 1942, the Kriegsmarine switched the U-boats to a completely new Enigma key (TRITON), which used special upgraded Enigma machines. This new key could not be read by codebreakers; the Allies no longer knew where the U-boat patrol lines were. This made it far more difficult to evade contact, and the wolf packs ravaged many convoys. This state persisted for ten months. To obtain information on submarine movements the Allies had to make do with HF/DF fixes and decrypts of Kriegsmarine messages encoded on earlier Enigma machines. These messages included signals from coastal forces about U-boat arrivals and departures at their bases in France, and the reports from the U-boat training command. From these clues, Commander Rodger Winn’s Admiralty Submarine Tracking Room supplied their best estimates of submarine movements, but this information was not enough.

Then on October 30, crewmen from HMS Petard salvaged Enigma material from German submarine U-559 as she foundered off Port Said. This allowed the codebreakers to break TRITON, a feat credited to Alan Turing. By December 1942, Enigma decrypts were again disclosing U-boat patrol positions, and shipping losses declined dramatically once more.

After Convoy ON 154, winter weather provided a brief respite from the fighting in January before convoys SC 118 and ON 166 in February 1943, but in the spring, convoy battles started up again with the same ferocity. There were so many U-boats on patrol in the North Atlantic, it was difficult for convoys to evade detection, resulting in a succession of vicious battles.

Also, in March the Germans added a refinement to the U-boat Enigma key, which blinded the Allied codebreakers for 10 days. That month saw the battles of convoys UGS 6, HX 228, SC 121, SC 122 and HX 229. One hundred and twenty ships were sunk worldwide, 82 ships of 476,000 tons in the Atlantic, while 12 U-boats were destroyed.

The supply situation in Britain was such there was talk of being unable to continue the war, with supplies of fuel being particularly low. The situation was so bad that the British considered abandoning convoys entirely. The next two months saw a complete reversal of fortunes.

In April, losses of U-boats increased while their kills fell significantly. Only 39 ships of 235,000 tons were sunk in the Atlantic, and 15 U-boats were destroyed. By May, wolf packs no longer had the advantage and that month became known as Black May in the U-Boat Arm (U-Boot Waffe). The turning point was the battle centered on slow convoy ONS 5 (April–May 1943). Made up of 43 merchantmen escorted by 16 warships, it was attacked by a pack of 30 U-boats. Although 13 merchant ships were lost, six U-boats were sunk by the escorts or Allied aircraft. Despite a storm which scattered the convoy, the merchantmen reached the protection of land-based air cover, causing Dönitz to call off the attack. Two weeks later, SC 130 saw at least three U-boats destroyed and at least one U-boat damaged for no losses. Faced with disaster, Dönitz called off operations in the North Atlantic, saying, “We had lost the Battle of the Atlantic.”

In all, 43 U-boats were destroyed in May, 34 in the Atlantic. This was 25% of German U-boat arm (U-Bootwaffe) (UBW)’s total operational strength. The Allies lost 58 ships in the same period, 34 of these (totaling 134,000 tons) in the Atlantic.

The Battle of the Atlantic was won by the Allies in two months. There was no single reason for this; what had changed was a sudden convergence of technologies, combined with an increase in Allied resources.

The mid-Atlantic gap that had been unreachable by aircraft was closed by long-range B-24 Liberators. At the May 1943 Trident conference, Admiral King requested General Henry H. Arnold send a squadron of ASW-configured B-24s to Newfoundland to strengthen the air escort of North Atlantic convoys. General Arnold ordered his squadron commander to engage only in “offensive” search and attack missions and not in escort of convoys. In June, General Arnold suggested the Navy assume responsibility for ASW operations. Admiral King requested the Army’s ASW-configured B-24s in exchange for an equal number of unmodified Navy B-24s. Agreement was reached in July and the exchange was completed in September 1943.

Further air cover was provided by the introduction of merchant aircraft carriers (MAC ships), and later the growing numbers of American-built escort carriers. Primarily flying Grumman F4F Wildcats and Grumman TBF Avengers, they sailed with the convoys and provided much-needed air cover and patrols all the way across the Atlantic.

Larger numbers of escorts became available, both as a result of American building programs and the release of escorts committed to the North African landings during November and December 1942. In particular, destroyer escorts (similar British ships were known as frigates) were designed, which could be built more economically than expensive fleet destroyers and were more seaworthy than corvettes. There would not only be sufficient numbers of escorts to securely protect convoys, they could also form hunter-killer groups (often centered on escort carriers) to aggressively hunt U-boats.

By spring 1943, the British had developed an effective sea-scanning radar small enough to be carried in patrol aircraft armed with airborne depth charges. Centimetric radar greatly improved interception and was undetectable by Metox. Fitted with it, RAF Coastal Command sank more U-Boats than any other Allied service in the last three years of the war. During 1943 U-boat losses amounted to 258 to all causes. Of this total, 90 were sunk and 51 damaged by Coastal Command.

Allied air forces developed tactics and technology to make the Bay of Biscay, the main route for France-based U-boats, very dangerous to submarines. The Leigh Light enabled attacks on U-boats recharging their batteries on the surface at night. Fliegerführer Atlantik responded by providing fighter cover for U-boats moving into and returning from the Atlantic and for returning blockade runners. Nevertheless, with intelligence coming from resistance personnel in the ports themselves, the last few miles to and from port proved hazardous to U-boats.

Dönitz’s aim in this tonnage war was to sink Allied ships faster than they could be replaced; as losses fell and production rose, particularly in the United States, this became impossible.

Despite U-boat operations in the region (centered in the Atlantic Narrows between Brazil and West Africa) beginning autumn 1940, only in the following year did these start to raise serious concern in Washington. This perceived threat caused the U.S. to decide that the introduction of U.S. forces along Brazil’s coast would be valuable. After negotiations with Brazilian Foreign Minister Osvaldo Aranha (on behalf of dictator Getúlio Vargas), these were introduced in second half of 1941.

Germany and Italy subsequently extended their submarine attacks to include Brazilian ships wherever they were, and from April 1942 were found in Brazilian waters. On 22 May 1942, the first Brazilian attack (although unsuccessful) was carried out by Brazilian Air Force aircraft on the Italian submarine Barbarigo. After a series of attacks on merchant vessels off the Brazilian coast by U-507, Brazil officially entered the war on 22 August 1942, offering an important addition to the Allied strategic position in the South Atlantic.

Although the Brazilian Navy was small, it had modern minelayers suitable for coastal convoy escort and aircraft which needed only small modifications to become suitable for maritime patrol. During its three years of war, mainly in Caribbean and South Atlantic, alone and in conjunction with the U.S., Brazil escorted 3,167 ships in 614 convoys, totaling 16,500,000 tons, with losses of 0.1%. Brazil saw three of its warships sunk and 486 men killed in action (332 in the cruiser Bahia); 972 seamen and civilian passengers were also lost aboard the 32 Brazilian merchant vessels attacked by enemy submarines. American and Brazilian air and naval forces worked closely together until the end of the Battle. One example was the sinking of German submarine U-199 in July 1943, by a coordinated action of Brazilian and American aircraft. Only in Brazilian waters, eleven other Axis submarines were known sunk between January and September 1943—the Italian Archimede and ten German boats: U-128, U-161, U-164, U-507, U-513, U-590, U-591, U-598, U-604, and U-662.

By fall 1943, the decreasing number of Allied shipping losses in South Atlantic coincided with the increasing elimination of Axis submarines operating there. From then, the battle in the region was lost for Germans, even with the most of remaining submarines in the region receiving official order of withdrawal only in August of the following year, and with (Baron Jedburgh) the last Allied merchant ship sunk by a U-Boat (U-532) there, on 10 March 1945.

Germany made several attempts to upgrade the U-boat force, while awaiting the next generation of U-boats: the Walter and Elektroboot types. Among these upgrades were improved anti-aircraft defenses, radar detectors, better torpedoes, decoys, and Schnorchel (snorkels), which allowed U-boats to run underwater off their diesel engines.

The September 1943 return to the offensive in the North Atlantic saw initial success, with an attack on ONS 18 and ON 202. A series of battles saw fewer victories and more losses for UbW. After four months, BdU again called off the offensive; eight ships of 56,000 tons and six warships had been sunk for the loss of 39 U-boats, a catastrophic loss ratio.

The Luftwaffe also introduced the long-range He 177 bomber and Henschel Hs 293 guided glider bomb, which claimed a number of victims, but Allied air superiority prevented them from being a major threat.

To counter Allied air power, UbW increased the anti-aircraft armament of U-boats, and introduced specially-equipped “flak boats”; they were to stay surfaced and engage in combat with attacking planes, rather than dive and evade. These developments initially caught RAF pilots by surprise. However, a U-boat which remained surfaced increased the risk of its pressure hull being punctured, making it unable to submerge, while attacking pilots often called in surface ships if they met too much resistance, orbiting out of range of the U-boat’s guns to maintain contact. Should the U-boat dive, the aircraft would attack. Immediate diving remained a U-boat’s best survival tactic when encountering aircraft. According to German sources, only six aircraft were shot down by U-flaks in six missions (three by U-441, one each by U-256, U-621 and U-953).

The Germans also introduced improved radar warning units, such as Wanze.

To fool Allied sonar, the Germans deployed Bold canisters (which the British called Submarine Bubble Target) to generate false echoes, as well as Sieglinde self-propelled decoys.

The development of torpedoes also improved with the pattern-running Flächen-Absuch-Torpedo (FAT), which ran a pre-programmed course criss-crossing the convoy path, and the G7es acoustic torpedo (known to the Allies as German Naval Acoustic Torpedo, GNAT), which homed on the propeller noise of a target. This was initially very effective, but the Allies quickly developed counter-measures, both tactical (“Step-Aside”) and technical (“Foxer”).

None of the German measures were truly effective, and by 1943 Allied air power was so strong U-boats were being attacked in the Bay of Biscay shortly after leaving port. The Germans had lost the technological race. Their actions were restricted to lone-wolf attacks in British coastal waters, and preparation to resist the expected invasion of France.

Over the next two years many U-boats were sunk, usually with all hands. With the battle won by the Allies, supplies poured into Britain and North Africa for the eventual liberation of Europe. The U-boats were further critically hampered after D-Day by the loss of their bases in France to the advancing Allied armies.

Late in the war, the Germans introduced the Elektroboot: the Type XXI and short range Type XXIII. The Type XXI could run submerged at 17 knots (31 km/h), faster than a Type VII at full speed surfaced, and faster than Allied corvettes. Designs were finalized in January 1943 but mass-production of the new types did not start until 1944. By 1945, just five Type XXIII and one Type XXI boats were operational. The Type XXIIIs made nine patrols, sinking five ships in the first five months of 1945; only one combat patrol was carried out by a Type XXI before the war ended, making no contact with the enemy.

As the Allied armies closed in on the U-boat bases in North Germany, over 200 boats were scuttled to avoid capture; those of most value attempted to flee to bases in Norway. In the first week of May, twenty-three boats were sunk in the Baltic while attempting this journey.

The last actions in American waters took place on May 5–6, 1945, which saw the sinking of SS Black Point and the destruction of U-853 and U-881 in separate incidents.

The last actions of the Battle of the Atlantic were on May 7–8. U-320 was the last U-boat sunk in action, by an RAF Catalina; while the Norwegian minesweeper NYMS 382 and the freighters Sneland I and Avondale Park were torpedoed in separate incidents, just hours before the German surrender.

The remaining U-boats, at sea or in port, were surrendered to the Allies, 174 in total. Most were destroyed in Operation Deadlight after the war.

The Germans failed to stop the flow of strategic supplies to Britain. This failure resulted in the build-up of troops and supplies needed for the D-Day landings. The defeat of the U-boat was a necessary precursor for accumulation of Allied troops and supplies to ensure Germany’s defeat.

Victory was achieved at a huge cost: between 1939 and 1945, 3,500 Allied merchant ships (totaling 14.5 million gross tons) and 175 Allied warships were sunk and some 72,200 Allied naval and merchant seamen lost their lives. The Germans lost 783 U-boats and approximately 30,000 sailors killed, three-quarters of Germany’s 40,000-man U-boat fleet.

Allies: 36,200 sailors; 36,000 merchant seamen; 3,500 merchant vessels; 175 warships.

Germans: 30,000 sailors; 783 submarines.

During the Second World War nearly one third of the world’s merchant shipping was British. Over 30,000 men from the British Merchant Navy lost their lives between 1939 and 1945. More than 2,400 British ships were sunk. The ships were crewed by sailors from all over the British Empire, including some 25% from India and China, and 5% from the West Indies, Middle East and Africa. The British officers wore uniforms very similar to those of the Royal Navy. The ordinary sailors, however, had no uniform and when on leave in Britain they sometimes suffered taunts and abuse from civilians who mistakenly thought the crewmen were shirking their patriotic duty to enlist in the armed forces. To counter this, the crewmen were issued with an ‘MN’ lapel badge to indicate they were serving in the Merchant Navy.

The British merchant fleet was made up of vessels from the many and varied private shipping lines, examples being the tankers of the British Tanker Company and the freighters of Ellerman and Silver Lines. The British government, via the Ministry of War Transport (MoWT), also had new ships built during the course of the war, these being known as Empire ships.

In addition to its existing merchant fleet, United States shipyards built 2,710 Liberty ships totaling 38.5 million tons, vastly exceeding the 14 million tons of shipping the German U-boats were able to sink during the war.

Canada’s Merchant Navy was vital to the Allied cause during World War II. More than 70 Canadian merchant vessels were lost. 1,600 merchant sailors were killed, including eight women. Information obtained by British agents regarding German shipping movements led Canada to conscript all its merchant vessels two weeks before actually declaring war, with the Royal Canadian Navy taking control of all shipping August 26, 1939.

At the outbreak of the war, Canada possessed 38 ocean-going merchant vessels. By the end of hostilities, in excess of 400 cargo ships had been built in Canada.

With the exception of the Japanese invasion of the Alaskan Aleutian Islands, the Battle of the Atlantic was the only battle of the Second World War to touch North American shores. U-boats disrupted coastal shipping from the Caribbean to Halifax, during the summer of 1942, and even entered into battle in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Canadian officers wore uniforms which were virtually identical in style to those of the British. The ordinary seamen were issued with an ‘MN Canada’ badge to wear on their lapel when on leave, to indicate their service.

At the end of the war, Rear Admiral Leonard Murray, Commander-in-Chief Canadian North Atlantic, remarked, ...”the Battle of the Atlantic was not won by any Navy or Air Force, it was won by the courage, fortitude and determination of the British and Allied Merchant Navy.”

Before the war, Norway’s Merchant Navy was the fourth largest in the world and its ships were the most modern. The Germans and the Allies both recognized the great importance of Norway’s merchant fleet, and following Germany’s invasion of Norway in April 1940, both sides sought control of the ships. Norwegian Nazi puppet leader Vidkun Quisling ordered all Norwegian ships to sail to German, Italian or neutral ports. He was ignored. All Norwegian ships decided to serve at the disposal of the Allies. The vessels of the Norwegian Merchant Navy were placed under the control of the government-run Nortraship, with headquarters in London and New York.

Nortraship’s modern ships, especially its tankers, were extremely important to the Allies. Norwegian tankers carried nearly one-third of the oil transported to Britain during the war. Records show that 694 Norwegian ships were sunk during this period, representing 47% of the total fleet. At the end of the war in 1945, the Norwegian merchant fleet was estimated at 1,378 ships. More than 3,700 Norwegian merchant seamen lost their lives.

It is maintained by some historians that the U-boat Arm came close to winning the Battle of the Atlantic; that the Allies were almost defeated; and that Britain was brought to the brink of starvation. Others, including Blair and Alan Levin, disagree; Levin states this is “a misperception,” and that “it is doubtful they ever came close” to achieving this.

The focus on U-boat successes, the “aces” and their scores, the convoys attacked, and the ships sunk, serves to camouflage the Kriegsmarine’s manifold failures. In particular, this was because most of the ships sunk by U-boat were not in convoys, but sailing alone, or having become separated from convoys.

At no time during the campaign were supply lines to Britain interrupted; even during the Bismarck crisis, convoys sailed as usual (although with heavier escorts). In all, during the Atlantic Campaign only 10% of transatlantic convoys that sailed were attacked, and of those attacked only 10% on average of the ships were lost. Overall, more than 99% of all ships sailing to and from the British Isles during World War II did so successfully.

Despite their efforts, the Axis powers were unable to prevent the build-up of Allied invasion forces for the liberation of Europe. In November 1942, at the height of the Atlantic campaign, the U.S. Navy escorted the Operation Torch invasion fleet 3,000 mi (4,800 km) across the Atlantic without hindrance, or even being detected. (This may be the ultimate example of the Allied practice of evasive routing.) In 1943 and 1944 the Allies transported some 3 million American and Allied servicemen across the Atlantic without significant loss. By 1945 the USN was able to wipe out in mid-Atlantic with little real difficulty a wolf-pack suspected of carrying V-weapons.

Third, and unlike the Allies, the Germans were never able to mount a comprehensive blockade of Britain. Nor were they able to focus their effort by targeting the most valuable cargoes, the eastbound traffic carrying war materiel. Instead they were reduced to the slow attrition of a tonnage war. To win this, the U-boat arm had to sink 300,000 GRT per month in order to overwhelm Britain’s shipbuilding capacity and reduce her merchant marine strength.

In only four out of the first 27 months of the war did Germany achieve this target, while after December 1941, when Britain was joined by the U.S. merchant marine and ship yards the target effectively doubled. As a result, the Axis needed to sink 700,000 GRT per month; as the massive expansion of the U.S. shipbuilding industry took effect this target increased still further. The 700,000 ton target was achieved in only one month, November 1942, while after May 1943 average sinkings dropped to less than one tenth of that figure.

By the end of the war, although the U-boat arm had sunk 6,000 ships totaling 21 million GRT, the Allies had built over 38 million tons of new shipping.

The reason for the misperception that the German blockade came close to success may be found in post-war writings by both German and British authors. Blair attributes the distortion to “propagandists” who “glorified and exaggerated the successes of German submariners,” while he believes Allied writers “had their own reasons for exaggerating the peril.”

Dan van der Vat suggests that, unlike the U.S., or Canada and Britain’s other dominions, which were protected by oceanic distances, Britain was at the end of the transatlantic supply route closest to German bases; for Britain it was a lifeline. It is this which led to Churchill’s concerns. Coupled with a series of major convoy battles in the space of a month, it undermined confidence in the convoy system in March 1943, to the point Britain considered abandoning it, not realizing the U-boat had already effectively been defeated. These were “over-pessimistic threat assessments,” Blair concludes: “At no time did the German U-boat force ever come close to winning the Battle of the Atlantic or bringing on the collapse of Great Britain.”

Media

Action in the North Atlantic – 1943 American war film about sailors aboard a Liberty ship in the U.S. Merchant Marine battling a German U-boat.

Das Boot – Film about World War II submarine warfare.

Bibliography

Barone, João (2013). 1942: O Brasil e sua guerra quase desconhecida [1942: Brazil and its almost Forgotten War] (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro.

Bennett, William J (2007). America: The Last Best Hope, Volume 2: From a World at War to the Triumph of Freedom 1914–1989. United States: Nelson Current.

Buckley, John (1995). The RAF and Trade Defence, 1919–1945: Constant Endeavour. Ryburn.

Buckley, John (1998). Air Power in the Age of Total War. UCL Press.

Blair, Clay, Jr. (1996a). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939–1942. I. Cassell.

Blair, Clay, Jr. (1996b). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunted 1942–1945. II. Cassell.

Blair, Clay, Jr. (1976). Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan (2nd ed.). New York: Bantam.

Bowling, R. A. (December 1969). "Escort of Convoy: Still the Only Way". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. 95 (12): 46–56.

Bowyer, Chaz (1979). Coastal Command at War. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Ltd.

Carruthers, Bob (2011). The U-Boat War in the Atlantic: Volume III: 1944–1945. Coda Books.

Carey, Alan C. (2004). Galloping Ghosts of the Brazilian Coast. Lincoln, NE USA: iUniverse, Inc.

Copeland, Jack (2004). "Enigma". In Copeland, B. Jack (ed.). The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma.

Costello, John; Hughes, Terry (1977). The Battle of the Atlantic. London: Collins.

Edgerton, David (2011). Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources, and Experts in the Second World War. Oxford University Press, USA. I

Giorgerini, Giorgio (2002). Uomini sul fondo : storia del sommergibilismo italiano dalle origini a oggi [Men on the bottom: the history of Italian submarines from the beginning to the present] (in Italian). Milano: Mondadori.

Hendrie, Andrew (2006). The Cinderella Service: RAF Coastal Command 1939–1945. Pen & Sword Aviation.

Ireland, Bernard (2003). Battle of the Atlantic. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books.

Kohnen, David (Winter 2007). "Tombstone of Victory: Tracking the U-505 From German Commerce Raider to American War Memorial, 1944–1954". The Journal of America's Military Past. 32 (3): 5–33.