by Floyd A. Cave

Published in 1948

Current debate over Germany's war guilt in the Second World War ranges between theories attributing a deliberate plan on the part of Germany's Nazi leaders to plunge the world into another holocaust and those emphasizing ultimate geographic, economic, and cultural factors which determined the course of German foreign policy. Probably there is a measure of truth in both of these conceptions. Certainly the geographical circumstances of the life of the German nation are closely integrated with the character of the German people and fused together they create those unique qualities which have made Germany what she is.

The conditions of geographical space have placed Germany in the center of Europe where her energetic and highly efficient people have naturally assumed leadership—scientific, cultural, and military. Germany's rapidly expanding population and industrial superiority seemed to justify her statesmen in seeking additional "living space" or at least control over trade relationships with neighboring nations. The unified Reich achieved in 1871 by Bismarck, although much stronger than preceding confederations, was limited in space, arable land, and raw materials. The relative prosperity of the pre-World War I period, however, rather than satisfying German ambitions, gave definite impetus to her imperial quest. A desire for a higher standard of living does not, therefore, seem to have constituted a determining factor in Germany's attempt to break through the iron ring which encircled her.

Attention, too, must be given to the basic elements in Germany's rise to power as a great nation. Prussia's military successes against Denmark in the Danish War (1864), in the Six Weeks War (1866), and in the Franco-Prussian War (1870), the military traditions of the Junker class, and the existence of a warrior class headed by the German General Staff helped to mold a military tradition and develop the habit of resorting to war as a means of successfully achieving the national ambitions of the German people. When to this is added the fact that no well-established traditions of popular sovereignty and self-government existed among the German people, the reasons for support of the Nazi movement and the resort to the arbitrament of war become clearer. Generations of indoctrination and usage accustomed Germans to strong government and one-man rule. Successes in previous wars and contempt for the military prowess of her opponents made entry into a new war less difficult for the Nazis to engineer.

The peace treaties deprived Germany of considerable territory both in the East and the West, leaving her with a homeland of approximately 181,668 square miles and a population, in 1939, of nearly 70,000,000 people. The pressure of the Slav populations on her eastern flank was intensified after the war because of the recreation of Poland and Czechoslovakia, and the rapid growth of Slavic populations in this area compared with that of the German population. In the West, France, greatly strengthened by Germany's defeat on the war, endeavored to consolidate her temporary continental supremacy through a system of alliances with the Succession States whose interests were at odds with those of Germany. Across the English Channel, the British navy stood guard over the sea lanes of the Baltic and North Seas.

Blocked by her powerful neighbors in the East, West, and North from normal expansion in those directions, the slowly recuperating German nation seemed destined to collaborate with the Anglo-French Allies and to direct, with their approval, its expansionist activities southward over Austria and down the Danube Valley. In this region, the Western Allies hoped Germany would run afoul of Russia once more and spend her rising energies in such a contest, thus removing the threat of German pressures in the West.

In German eyes, European hegemony rightfully belonged to the Reich as the most powerful state in Europe with the most productive industrial plant, the most efficient army, and the most highly skilled and cultured population. Conceiving of Germany as having been betrayed and ruined by the Entente nations who added insult to injury by attaching to the German people the burden of "war guilt," leaders of the Reich saw Germany's position as one of being thwarted by her jealous neighbors from achieving her rightful place in the European family and her natural development as a great nation. Undoubtedly, many factors contributed to Germany's decision once again to put her fate to the test of battle, but most important among them was the pride of the German people in themselves as a great and warlike nation to whom European leadership right fully belonged, and their lust to regain Germany's former dominance. Fear of the encroaching Slavs, jealousy off the prosperity of the Western powers, hatred of the peace settlement which tried to reduce Germany to a condition of permanent inferiority, and pride in Germany's past military successes all played their part; but none or all of them imposed an inescapable choice upon Germany. Her fateful decision was deliberately and freely made by her leaders and supported by her people.

Plans were carefully drawn up far in advance by Germany's political and military leaders. The peaceful period between two World Wars was employed as a time to recuperate and plot further attempts to destroy her enemies. Hitler talked of Lebensraum (living space), conceiving of it not only as more land whose usufruct would replenish German larders, but as more adequate space in which Germany might expand her political and military power to a maximum. The cautious and clever policies followed by the Führer in the earlier years of his regime were accompanied by amazing successes. The crumbling power of the states opposing his advances revealed the enormous possibilities for a German victory not only over Europe but over the entire world. The stakes were immensely valuable and, in Hitler's view, well worth the risks.

Crisis at the End of World War I

The surrender of their principles of pacifism and international brotherhood at the outbreak of World War I in favor of the Fatherland in its hour of peril did not blind the Socialists and other radical parties to the anti-democratic features of the government, particularly as exaggerated by the exigencies of wartime. At best, the government of the German Empire before the war was upper-class and reactionary. The Kaiser himself was entrenched in a very powerful position through his control over the Chancellor and his cabinet, and his ability on his own volition to make war. These autocratic powers were reinforced by the Emperor's position as King of Prussia, whose territory and population constituted more than half of the area and population of the Reich.

Through his autocratic position as King of Prussia, the Kaiser not only dominated the greater part of the Empire but was able, by means of his control over the Prussian delegation to the Bundesrat, to dictate the policies of that body. The Bundesrat, representative of the ruling house of the German states, preponderated in lawmaking and the determination of state policies. The lower house, the Reichstag, though based upon the male electorate, lacked control over the executive and the budget and had little to do with legislation. In consequence, the government was irresponsible and gave little heed to the wishes of the common man.

To this unsatisfactory condition was added the extension of powers over the government by the General Staff during the war. Acting under legal provisions regarding a state of siege, the army authorities took control of affairs. Executive powers were turned over by civil authorities to military representatives in the various districts. These military officials functioned under General Ludendorff who in turn owed responsibility to the Kaiser. Decree-making powers conferred upon the Reich Government in 1914 were so extensive that they virtually made the existence of the legislative branches of the government unnecessary. The military dictatorship thus imposed upon the German people was administered with little regard for the social pressures building up from below, and the policies pursued were upper-class, imperialistic, and anti-liberal. Many Socialists, therefore, who at the war's beginning had supported the government, began, as the struggle proceeded, to shift their position.

The effect of this was to split the party. As early as 1915 a minority of the Majority Socialists took their stand against extension of war credits and, by 1917, they had organized the Independent Social Democratic Party which favored immediate peace by offering to forswear any claims to territorial gains made during the war. Extreme radicals, still further to the left, followed the lead of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, becoming known as Spartacists. Openly communistic, the Spartacists advocated immediate peace and the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat. Socialist agitation for peace found ready acceptance among the masses of the war-weary population, starved by the effects of the Allied blockade and poor harvests, and disillusioned by German reverses. By the spring of 1917, moderate parties took up the peace cry and in June 1917, the Catholic Centrists, Progressives, and Socialists in the Reichstag voted a Peace Resolution, calling upon the government to end the war. Although the army-dominated regime refused to respond, the continued loss of popular morale finally forced a shift of chancellors from Michaelis to Hertling to Prince Maximilian of Baden.

Under the first two, the Army High Command made few concessions and at Brest-Litovsk forced a conqueror's peace upon the Bolsheviks. The Russian Revolution, however, which took Russia out of the war, had a tremendous effect upon the German people, and the urge to end the war was given great momentum by Bolshevik propaganda which, added to Allied efforts in this field, made great inroads upon the German will-to-war. Spreading strikes and labor sabotage marked the dying struggles of the Hohenzollern Empire. Under Prince Maximilian, a coalition cabinet was formed which included in its membership two Majority Socialists, Philip Scheidemann and Gustave Bauer.

Yielding to President Wilson's demands for a republican form of government because Germany's leaders saw defeat staring them in the face and hoped by this means to make an easier peace, Prince Maximilian was appointed Chancellor, heading a cabinet formed from majority parties in the Reichstag. In October 1918, this ministry enacted legislation creating a responsible, parliamentary form of government. The mutiny of naval contingents at Kiel and the staggering defeats inflicted upon the German armies by Allied forces, finally forced Ludendorff, in desperation, to ask for peace. Negotiations were undertaken with the Allies and, on 11 November, the Armistice was signed.

Meanwhile, the domestic situation rapidly deteriorated into a nation-wide revolution. The Kaiser and his family fled to Holland where, on 28 November, he abdicated. Reigning houses all over Germany followed Wilhelm's example, leaving national and state governments in the hands of hastily improvised republican regimes. At Berlin, a Council of People's Commissars was created consisting of three Majority and three Independent Socialists under the joint chairmanship of Friedrich Ebert and Hugo Haase, the Independent Socialist. Fully confirmed in their Communist position, the Spartacists refused to collaborate and began to agitate against the temporary government. A split also developed between the Independent and Majority Socialists, over the question of the degree and rapidity of the socialization of the government.

These issues had to be submitted to a decision of the people. The Soldiers and Workers Council that had mushroomed up all over the country held a national congress in December 1918, which excluded Communists and rejected the radical stand of the Independent Socialists. Thus the fateful decision was made which diverted Germany away from the road to Communism. The solidity and conservatism of the powerful middle class in Germany turned the tide and killed the hopes of the Bolshevist revolutionaries in the Kremlin who were waiting for Germany to go Communist, and thus open the way into Western Europe for Marxism.

Unwilling to submit to this decision, the Spartacists openly attacked the new governments. In this they were most successful in Berlin where with the aid of armed workmen and ex-service men, they seized, and for a time held, the city government. The Ebert-Haase Government at last was driven to recruiting volunteer forces with which they suppressed the revolt.

The Weimar Constitution

The victory of the moderate elements was confirmed in the elections held 19 January 1919. The military clique and the Junker elements were for a time separated from their dominating positions in the government. The Social Democrats with 163 seats became the largest party in the Assembly. The Centrists received 88, the Democrats 75, the Nationalists 42, the Independent Socialists 22, and the People's Party 21 seats. A coalition of Social Democrats, Centrists, and Democrats with 346 out of 421 seats, therefore, overwhelmingly controlled the Assembly. When the coalition was formed, the temporary government resigned its powers to the "Weimar Coalition," which thereupon became the temporary government of Germany and carried on governmental activities while the Assembly was drafting the new constitution. Friedrich Ebert, co-chairman of the Commission of Commissars, and a saddle maker by trade, was elected President of the Republic by the Assembly.

The drafting of the new constitution was expedited by a rough draft prepared by Hugo Preuss, the so-called "father of the constitution" and a member of the Democratic Party. The provisions of this rather lengthy instrument, which was finally promulgated on 11 August, reflect the numerous compromises which had to be worked out to satisfy the requirements of the Socialists, Democrats, Centrists, and advocates of states' rights. The purpose to establish a truly democratic, representative republic is reflected in the provisions which attribute ultimate political power to the people. The desire to retain important elements of federalism is shown by the organization of republican states, or Laender. Yet the delegation of greater powers to the national government indicated the centralizing tendency. Particularly noticeable in this respect were the provisions enabling the federal government to enact legislation upon local matters where they assumed national significance. The socialist influence was apparent in the powers conceded to the federal government over railways and other forms of transportation, natural resources, education, and poor relief. The right of the federal government to undertake measures for nationalization of basic industries was included. Nevertheless, the states retained considerable autonomy.

Legislative authority was vested in a bi-cameral legislature composed of the Reichsrat, or upper house, and the Reichstag, or lower house. The Reichsrat consisted of about seventy members representing the states proportionally, roughly on the basis of one for every 700,000 (later every 1,000,000) of population. Prussia, however, was limited to two-fifths of the membership. Definitely a secondary chamber, the Reichsrat could exercise a suspensory veto on legislation or refer questionable measures to a popular vote. Otherwise its powers were minimal.

The Reichstag, composed of over 500 members and elected by universal suffrage under a system of proportional representation for a four-year period, was by far the more powerful of the two bodies. Able to overcome a veto of the Reichsrat by a two-thirds vote, the Reichstag could make laws on its own initiative. Moreover, its power to retire the cabinet gave it powers over the government not wielded by the upper house.

Executive power was vested in a president elected by popular vote for a seven-year term with indefinite privileges of re-election. All authority of an executive nature was nominally conferred upon the president; but through the power of counter-signature, the chancellor and his ministers actually carried on the government. Responsibility of the cabinet to parliament was secured by the requirement of resignation on an adverse vote in the chamber. These provisions seemed to install a parliamentary system of the English type. Yet, the power of the president to dissolve the Reichstag and dismiss the cabinet, gave him a strong check on their actions. More important still, the popular prestige of the president as an elected leader enabled him to adopt an independent position. Under Article 48, the president in times of national emergency could suspend popular rights and operate the government under decree-powers. The use of decree-powers by the president and the maintenance of cabinets responsible to him rather than to parliament were a prelude to the advent of dictatorship. No provision was made for a vice-president.

An elaborate Bill of Rights guaranteed the liberties of the people, but these were subject to interpretation by the government. Provisions for initiative and referendum in both state and national governments pointed the way to full-scale popular participation in political affairs but, as events transpired, these were not widely used. Representation of workers and employers in local, regional, and national economic councils, which had power to consider all legislation pertaining to industrial matters and to make recommendations to parliament, marked an innovation in government procedures in relation to labor-management relations. This departure, also, failed to develop the importance which the constitution-makers predicted for it. Adopted by the Assembly on 31 July, by a vote of 262 to 75, the new constitution was signed by President Ebert on 11 August, and went into effect three days later. Thus, the new Republic was launched upon its uncertain course.

The Problems Confronting the New Republic

The provisional government had been able with difficulty to cope with Communist (Spartacist) uprisings throughout the country. Large-scale Communist uprisings in Berlin and Bavaria, where Kurt Eisner, the Bavarian Premier, had been killed and a Soviet republic proclaimed, had threatened for a time the stability of the state but were eventually put down by armed force. The decision of the soldiers' and workers' councils to adopt a moderate course and the results of the election to the Weimar Assembly heavily retarded the radical movement and, by 1920, the Communist threat had subsided. Meanwhile, the military clique with its allies the Junkers, Nationalists, Pan-Germanists, and other parties of the extreme right began an undercover campaign to regain control of the government. In March 1920, two irreconcilables, General von Luettwitz and a government official named Kapp, seized Berlin by armed force and installed Kapp as Chancellor. Ebert and his government fled the capital but the insurgents failed to make good their putsch because of lack of support from the army and conservative leaders but principally, perhaps, as a result of a general strike by the labor unions in Berlin, which responded to Ebert's appeal for help. Faced with complete chaos in the city, the Kapp regime collapsed and Kapp fled the country.

Defeat of the Kapp putsch strengthened the Republican Government and discouraged the conservatives but did not prevent them from continuing their seditious activities. Dissatisfaction of the German people with the hardships they had to face and with the exactions of the Allies under the Versailles Treaty gave them fertile ground in which to sow the seed of reaction. The Ebert regime was blamed for signing the peace treaty and submitting to forced disarmament, heavy indemnities, and loss of territory. Monarchists contrasted Germany's pitiable postwar condition with the glories of the past under the Hohenzollerns and called for restoration of the monarchy. In Bavaria, where the conservatives were strongly entrenched, a concerted attack was made against those responsible for bringing the war to an end. Even assassination was resorted to against Matthias Erzberger, leader of the Centrist Party, and Walther Rathenau, Democrat and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

The French occupation of the Ruhr in 1923, resulting from the failure of Germany to meet her reparations payments, was the occasion for another attempt by army and conservative leaders to seize power. Planned and organized by General Ludendorff and Adolf Hitler, the Beerhall putsch, at Munich on 8 November, was put down by force. Hitler was imprisoned but got off with a light sentence. A French plot to separate the Rhineland from Germany, which had been actively promoted for several years, came to a head at this time. With the active encouragement of French military authorities, separatist forces seized a number of critics in the area and proclaimed the "Autonomous Government of the Palatinate." Owing to American, British, and Belgian opposition, the French withdrew their support from the movement whereupon the leaders, discouraged by the failure of many key officials to rally their support, fell to quarreling among themselves, and the separatist government collapsed.

Economic Developments During the Twenties

By the end of the war, Germany found herself in a state of economic collapse. This was due partly to unintelligent financing of the war under which the government taxed the people lightly and relied upon bond issues and treasury notes for meeting 95% of war costs. Furthermore, concentration upon production of war materials and the consequent lack of consumers' goods and depreciation of capital equipment during the four years of war left the country in a state of economic exhaustion. Moreover, exactions of the Allies, particularly the forced contribution of $5,000,000,000 in gold, deprived the Republic of much of its available monetary stocks. To this must be added the losses in raw materials and arable land resulting from the treaties, the annual contributions on the reparations account, and the necessity of reconversion of industry to peacetime uses. In the disordered political situation resulting from the break-up of the Empire and the post-war revolution, these handicaps proved almost insurmountable.

Inflation

The vast supply of paper money put into circulation during the war plus the scarcity of goods after hostilities, as soon as war controls were removed, speedily produced inflation. Unsure of itself and still struggling to attain stability, the new government feared to impose a capital levy upon war profiteers and maintained tax rates after the war much lower than those of Great Britain and France. By May 1921, the mark had declined to about one-fifteenth of its pre-war value. The flight from the mark was proceeding at such a rapid rate that on 1 June the government began to buy gold at a premium. Inflation progressed so rapidly that by November 1922 the mark was worth only about one-thousandth of its former value. Government revenues declined in value because of inability to raise tax rates commensurate with the decline in purchasing power of the mark. In 1923, the monetary crisis reached its peak. The passive resistance policy of the Reich Government against French occupation of the Ruhr called for financial support of the idle workers who refused to labor for the French. In consequence, huge quantities of paper money were printed and distributed among German workers in the Ruhr. The result was collapse of all monetary controls and a runaway inflation. Prices rose to unbelievable heights, with the mark quoted at from 2.5 to 4 trillion to the dollar. Food riots and the refusal of farmers and merchants to exchange their produce for worthless currency indicated the imminence of complete economic chaos and called for drastic remedies.

In desperation, the Cabinet issued a decree in October 1923, establishing a new bank of issue and a new currency. Hjalmar Schacht, one of Germany's greatest bankers, was appointed special currency commissioner with instructions to restore stability to the monetary system. Orders were immediately issued stopping the printing of the old paper money, and a new currency was issued to circulate at the old value of 4.2 to the dollar. The old money was re-purchased at the rate of one to one trillion. Meanwhile, Finance Minister Luther by desperate exertions balanced the budget. A loan extended by the Allies under the Dawes Plan in October 1924 and evacuation of the Ruhr helped to restore financial equilibrium.

Results of the Inflation

The inflation of 1924 had tremendous consequences for the future of the country. Great industrialists of Germany profited immensely from the tremendous rise in prices. Taking advantage of the slower rise in ages and huge bank loans which they could pay back later with cheaper money, they reaped great profits. The borrowed funds were used to purchase new capital assets and retool old plants. On the other hand, the laboring class was reduced to poverty and the holdings of the middle class were wiped out. The result was to turn the workers toward Communism and the embittered middle class toward national socialism. With their savings, pensions, and insurance policies rendered valueless by the rate at which the old currency was redeemed, the desire of the middle class to support the existing order was seriously undermined.

The Period of Prosperity, 1924-1929

The wiping out of old obligations, however, gave a fillip to Germany's industry. Relieved of the burden of debts and with her factories in excellent shape because of the operations of the great financiers during the inflationary period, Germany now began to draw ahead of her competitors. Undeterred by the need to reconstruct devastated regions and aided materially by loans from abroad, German industry expanded production at a rapid ate. In spite of her losses in territory and raw materials, Germany proved able to overcome these handicaps. Scientific techniques learned during the war were applied to utilize available materials as substitutes for those lacking in Germany and to reduce costs. The extensive fields of brown coal were exploited to produce electric power, petroleum, oils, and other by-products. Water power was harnessed to industry. Steel production was increased in quantity and quality, and a large merchant marine constructed. In addition, German industry was "rationalized," i.e., large-scale corporations were organized for purposes of mass output, and extensive efforts were made to secure decreased costs and greater efficiency per unit of manpower.

During this period American money poured into Germany in the form of private loans. This artificial pump-priming was too good to last. True, the managers of German economy expanded markets for Germany's goods through conclusion of commercial treaties with the trading nations; but on the other hand, they discouraged imports by high protective tariffs and secretly diverted considerable capital and labor to production of military installations and armaments. With the former free-trade area in Russia blocked by the Soviet dictatorship and Germany's sales abroad impeded by competitive practices and goods of the Western nations, this fictitious bubble of prosperity soon burst. Under-consumption of goods resulting from unemployment of workers formerly employed in "rationalized" industries, and low prices of agricultural commodities added to the economic unbalance produced by a plethora of goods and absence of markets. Hence, the sudden withdrawal of American loans in 1929, because of the onset of the depression in the United States, revealed the flimsy character of the German boom and brought about a quick and devastating economic collapse.

Politics Under the Republic

Politics under the Republic were characterized by a gradual shift away from liberalism, and control of the Reichstag and cabinet from socialist, liberal, and center parties, toward the parties of reaction. The Reichstag elected in 1920 yielded a comfortable majority to the moderates and, until 1924, supported a coalition of Socialists, Democrats, and Centrists in the cabinet. Nevertheless, as has been previously indicated, the military, landed, and capitalist forces, while in abeyance, were well organized and powerfully supported by a backlog of tradition and sentiment among the people. Anti-republican propaganda, the effects of the inflation, and the French invasion of the Ruhr, produced in the elections of the Reichstag of May 1924 a decided popular swing to the right. This swing had in part been anticipated in 1922 by inclusion of the German People's Party in the Weimar coalition. Increased strength accorded the Nationalists in 1924, however, made it seem desirable to President Ebert to offer them the chancellorship. Resulting difficulties led Ebert to appoint Wilhelm Marx (Catholic Center Party) again as Chancellor over a moderate coalition. Nationalist votes were nevertheless required to implement provisions of the Dawes Plan, which were given in return for promises of certain positions in the government. Objections of the other parties to fulfillment of these pledges, however, precipitated a cabinet crisis and resulted in a dissolution of the Reichstag. The ensuing elections provided support for a moderate coalition for a while longer; but in 1925 the Socialists were excluded from the cabinet and a rightist coalition of Centrists, People's Party, and Nationalists established itself firmly in the saddle under Dr. Hans Luther.

The death of President Ebert in February 1925 deprived the Socialists of control of the presidency. Elected by the Assembly in 1920 as provisional president, Ebert had served the Republic well, guiding it between the dangerous shoals of extreme conservatism and communism. Ebert's death brought into play the constitutional provisions for popular election of the president. The requirement of an absolute majority on the first ballot or the holding of a second election, because of the spread of support among the list of seven candidates in the 29 March election, compelled a second balloting. Meanwhile, the parties jockeyed for position; the Centrists, Democrats, and Social Democrats joining forces behind Wilhelm Marx as their candidate, the Conservatives backing Field Marshal von Hindenburg, and the Communists, Ernst Thaelmann. Non-voters of rightist persuasion, attracted by the reputation and prestige of the great war hero, Hindenburg, turned out in such numbers as to give him a majority of nearly a million votes over the candidate of the moderate coalition. Fears of friends of the Republic that Hindenburg would repudiate the new regime and welcome a restoration of the monarchy were at least temporarily set at rest by the Field Marshal's oath to support the constitution and his subsequent policy of cooperation with the parliamentary system.

Yet conflicts between moderates and the Nationalists were on the increase. Intra-cabinet friction marked the period between 1925 and 1928. The general prosperity during this period saw a temporary reversal of the trend to the right when, in March 1928, the Reichstag was dissolved and the Social Democrats were restored to their original leadership in the Reichstag. Hermann Mueller, Socialist leader, formed a cabinet which, in 1929, comprised a five-party coalition of Socialists, Democrats, Centrists, People's and Bavarian People's Parties. Unhappily, the moderate resurgence was short-lived owing to the onset of the great depression. Unable to secure agreement on budgetary and unemployment problems, the Mueller Cabinet resigned in March 1930, and was succeeded by a new government under the chancellorship of Heinrich Bruening (Catholic Center Party). The new coalition, omitting the Socialists, shifted again toward the right.

Reasons for the Downfall of the Weimar Republic

Of the many causes for the failure of Germany's first experiment in democracy, the following are significant:

The shift in popular support away from the center and liberal parties which framed the Constitution to the conservative parties, which were sympathetic and even hostile to the Republic, undermined its foundations.

The civil service and the army were filled with monarchists and enemies of the Republic. These unfriendly persons occupying positions of leadership in key government and military posts in many cases used their influence to undermine the new regime.

The great inflation wiped out huge numbers of the middle class, the chief supporters of the Constitution, and turned them toward national socialism.

Class conflicts were exaggerated by the monetary crisis and still more by the great depression. These cleavages were intensified by the system of proportional representation, used in the election of members of the Reichstag, which split the parties into small "splinters." These pygmy parties manifested a strong tendency to stand rigidly by their programs and by their obstructionist policies prevented necessary cooperation in the cabinet, compelling the President ultimately to take matters into his own hands.

The existence of Article 48 in the Constitution encouraged the President to use his emergency-decree powers to give stability to the tottering cabinets in the later critical stages. More and more, cabinets were forced to depend upon the President for their continuance in office until finally the ministries were appointed and discussed without regard for majorities in the Reichstag. Thus, popular controls were abrogated and the trend to dictatorship began.

The forces of reaction and of counter-revolution were able to take advantage of the freedom of speech and press and the library of personal movement permitted under the Constitution to agitate, propagandize, and increase their strength while parties favorable to the Republic maintained a dangerous attitude of passivity.

The National Socialists were backed by the great industrialists and army leaders as well as by the Junkers, and were supported by large loans of money which they used to finance their propaganda campaigns and recruit followers.

Dissatisfaction of the people with the Weimar Republic, inflation and depression furnished the Nazis with exceptionally good campaign materials.

German traditions were authoritarian and the German people were unfamiliar with parliamentary government and democratic methods. Hence, when they were faced with profound crises threatening their security and economic welfare, they turned away from weak and divided cabinets to ward strong governments.

The existence of emergency provisions in the Constitution made it easy to subvert the Republic without making any substantial overt changes in the written constitution.

Seizure of Power by the National Socialists

In the three-year period between September 1930, and March 1933, the National Socialist Party increased its membership in the Reichstag from 12 to 288 deputies. The re-election of President von Hindenburg in April 1932 by a substantial popular majority convinced him that the people approved his strong policy of using his decree-powers to maintain cabinets in power regardless of their degree of support in the Reichstag. With the shift of popular support away from the center toward the extreme parties of the right and left, no common ground for cooperation could be found. Hence, presidential intervention, in Hindenburg's view, could not be avoided; yet he could not ignore the fact that many Majority Socialists had cast their votes for him, and he was bound by his oath of office to uphold the Republican constitution.

To turn over the chancellorship to Hitler was, as he recognized, in effect to agree to the overthrow of the Republic. The Bruening Cabinet, which had taken office on 30 March 1930, was resolved upon a middle course of balancing the budget, providing agricultural relief, and living up to Germany's international commitments. The economic crisis into which the world was plunged, however, revealed the gaps between economic classes and caused a drastic shift of popular support to the National Socialists on the right and the Communists on the left. In the elections of September 1930, called after dissolution of the Reichstag by the President, the Communist Party raised to over 4½ million its popular vote and increased its representation in the Reichstag from 54 to 77 seats. Even this alarming result seemed tame, however, in comparison with the National Socialist jump from 12 to 107 seats and from 809,000 to 6,400,000 popular votes. This portentous change gave a clear indication of the purpose of a large section of the people to give the Nazis a substantial voice in Parliament, and they became the second most numerous party in the House, giving place only to the Social Democrats. Yet the vote for Hindenburg showed where the wishes of the majority were. The position of the Cabinet now became virtually impossible as far as obtaining majority support in the Reichstag was concerned. Nevertheless, Bruening was maintained in power by Hindenburg's orders.

The resignation of the Cabinet on 30 May 1932, therefore, was probably due to Hindenburg's disapproval of Bruening's policies. The President's reasons, however, were not clear. Although the Cabinet was without a clear majority in the Reichstag, it had not been defeated. Perhaps pressure on Hindenburg by his Junker friends because of Bruening's proposal to take over and divide into smaller parcels the large landed estates in East Prussia and his disbanding of the Nazi Storm Troops influenced the Field Marshal's decision. In any case, Bruening's fall opened the way for von Papen and a little later, for von Schleicher as Chancellor.

Von Papen was expected to hold the line against the Nazis. Though not a National Socialist himself, his rightist tendencies were well known. Von Schleicher headed a cabinet of aristocrats. He himself endeavored to placate labor and resist Nazi aggression; but lacking support in the Reichstag, his efforts proved unavailing. Hindenburg's selection of these men indicated that he was yielding to rightist pressure though still not ready to accept Hitler. These appointments and the consequent ineffective resistance to Nazism set the stage for the seizure of power by Hitler.

The Von Papen Cabinets

Neither the von Papen or the von Schleicher Cabinet could weld together a supporting coalition in the Reichstag. Hindenburg, therefore, dissolved the lower house on 4 June, with the election scheduled for 31 July. Meanwhile, the von Papen government repealed the Bruening decrees for the maintenance of public safety, removed the ban on the Storm Troops, and threatened to take over the Government of Prussia. Alarmed by these moves, the South German states strengthened the prohibitions on the wearing of political uniforms and took greater precautions to preserve order. Removal by von Papen of the restrictions against the Brown Shirts and the special safeguards of private rights stimulated the Nazis to more violent outbreaks. Pre-election conflicts mounted in intensity and precipitated what amounted to a small-scale civil war, with the government favoring Nazi terrorists in their attacks upon Communists and Jews. In Altona, on 17 July, for example, a large-scale riot broke out, resulting in 15 killed and 70 wounded. These outbreaks compelled the Reich Government to re-establish strict controls over all public gatherings.

The Capture of the Prussian Government

On 20 July, von Papen invoked Article 48 of the Constitution as justification for a decree dismissing the Socialist Minister-President of Prussia, Otto Braun, and his government, and naming himself Reich Commissioner and Prussian Minister of the Interior, with Dr. Bracht acting as his deputy for Prussian affairs. Berlin and the province of Brandenburg were placed under martial law. Officials refusing to submit were arrested. Von Papen's action in staging a coup d'etat in Prussia was without doubt based upon his knowledge of Nazi support, his desire to destroy the last Socialist stronghold, and in particular to take control over the Prussian state police force, a powerful body second only to the Reichswehr in strength. Hence, his statement that his action was due to fear that the Prussian Government was unable to deal with the Communists was a pure rationalization.

The seizure of Prussia removed a potent check upon Nazi activities and greatly encouraged the National Socialists while it discouraged and intimidated the Socialist and Center parties. However, instead of taking equally violent counteraction, these parties contented themselves with protesting to the government and appealing the case of the ousted Prussian officials to the Supreme Court. The results of the 31 July election raised from 107 to 230 the number of Nazi seats in the Reichstag. While this was a huge gain over the 1930 result, it was not much larger than the Nazi vote in the April 1932 state elections and the movement seemed to be slowing down. The vote did not give the National Socialists anywhere near a majority in the Chamber though it did make them the largest party by nearly 100 votes. The Socialists lost ten seats and the Communists gained twelve, but the combined vote of the middle parties remained superior to the Nazi vote.

The Nazi Bid for Power

In the extremely advantageous situation in which he now found himself, Hitler saw his opportunity to gain leadership in the government. Accordingly, he demanded the chancellorship. A coalition with the Center parties was possible and the Centrists seemed willing to participate. Yet the party strife and mob violence fomented by the Nazis cast a shadow upon his demands, and friends of the Republic feared the consequences of his appointment. Despite renewed bans on mob violence, the Nazis' attacks upon Communists and Jews reached outrageous proportions so that even the pro-Nazi Reich Government was forced to arrest some of the worst perpetrators, try them in the emergency courts set up for this purpose, and sentence a few of them to death. In the face of these events, Hitler increased his demands for the chancellorship, asking, in addition, for a free hand in the cabinet.

On 13 August, Hindenburg called in Hitler and offered him a place in the cabinet but not the chancellorship. This Hitler refused. The impasse created by this situation necessitated another dissolution of the Reichstag to enable the people to try to find a way out of the dilemma. Dissolution, strangely enough, was opposed by the anti-parliamentary Nazis, perhaps because Hermann Göring, the Nazi candidate, was elected President of the Reichstag on 30 August when it met. Representations were made to President Hindenburg to try to persuade him not to dissolve the Reichstag. Owing to inability of Nazis and Centrists to agree, Hindenburg would not yield. On 12 September, when Parliament reconvened, it was dissolved by order of the President but not before a Communist motion of non-confidence was overwhelmingly approved by the Chamber. Elections were set for 6 November.

During its remaining days in office, the von Papen Government proceeded to enact legislation designed to benefit the business and agricultural classes. Tax-credit certificates were issued enabling the employers to cover part of their back-taxes. Bonuses were given to employers who hired additional workers, and a large public works program was set on foot. On the other hand, von Papen blamed the government's financial troubles upon excessive social insurance costs. These policies, plus his seizure of the Socialist Government of Prussia, indicated clearly by his anti-Socialist stand. The aggressive, anti-labor tendencies of the von Papen Cabinet were given somewhat of a check by the decision of the Reich Supreme Court on 25 October, declaring the suspension of the Prussian Ministry legal under Article 48 but only as regards the administrative functions of the Prussian Cabinet and then only for a limited period. The decision reinstated the Prussian Cabinet as far as performance of non-administrative functions were concerned but was not recognized in practice by the Reich Government.

Elections of 6 November 1932

The people's reaction to the political situation at the polls on 6 November failed to solve the fundamental deadlock of the parties of the extreme right and left. Nevertheless, the loss of thirty-four seats by the Nazis indicated decline of public favor and seemed to presage a turn of the tide. The Communist gain of eleven seats, however, was balanced by a loss of twelve deputies by the Social Democrats. The Nationalists, who alone of the parties in the Chamber were supporting the von Papen regime, gained fourteen seats but this could not guarantee sufficient support in the Reichstag to remove the stigma of a president-supported cabinet. Only one conclusion seemed possible in the face of this baffling result—the von Papen Government was not supported by the people. When leaders of the other parties were canvassed by von Papen under Hindenburg's instructions, only the People's Party would support the cabinet in addition to the Nationalists. Recognizing the futility of trying to carry on under the circumstances, the von Papen Cabinet resigned on 17 November.

Hindenburg's Negotiations with Hitler

With election results as they were, a coalition of the parties of the center could not secure a majority without including the Communists. Yet, Hindenburg had maintained von Papen by presidential fiat and could have chosen a Social Democrat under the same procedure had he so desired. The fact that he began to dicker with Hitler after the heavy loss of seats by the Nazis indicated clearly his rightist leanings. Being assured by Hitler that he could form a government acceptable to the Reichstag, von Hindenburg instructed him to verify this, subject to certain conditions. He was to formulate an acceptable program of industrial and economic reform, pledge himself not to restore the autonomy of Prussia, and not to interfere with Article 48 of the Constitution. In addition, Hindenburg demanded the final word on all ministerial appointments, and the right to appoint the Foreign Minister and Minister of Defense. Not satisfied with these restrictions which would have seriously crippled his freedom of action, Hitler on 23 November demanded the chancellorship with full power to act. This "all or nothing" request of Hitler was again rejected by Hindenburg, who thereupon named General von Schleicher Chancellor over a presidial government. This, as indicated above, was not the President's only alternative and illustrated his growing tendency to flout the plain terms of the Constitution.

The Von Schleicher Cabinet

The appointment of von Schleicher was Hindenburg's decision after it became clear that von Papen, in whom the Field Marshal had great confidence, could obtain no adequate support either in the Reichstag or among party leaders. The new cabinet made some concessions in its composition to the popular critics of Von Papen but contained many members whose sympathies were pro-Nazi. Von Schleicher, however, endeavored to calm the fears of supporters of the Republic, stating as his platform a program of providing employment, opposition to dictator ship, and a middle-of-the-road stand on economic questions. He placated the unions by restoring the social insurance system abolished by von Papen but maintained a strict silence regarding restoration of parliamentary government, reform of the constitution, and establishment of more authoritative government. As it proved, these moves were deliberately calculated to allay public alarm, and pave the way for the Nazi revolution.

Hitler Takes Over

Greatly encouraged by secret negotiations with the big industrialists, who urged him to modify his stubborn stand regarding the chancellorship, Hitler in January 1933 made a deal with von Papen whereby the latter would persuade Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as Chancellor in exchange for von Papen's appointment as Vice-Chancellor. Accordingly, von Schleicher's Cabinet was replaced by a Cabinet headed by Hitler. The coalition of National Socialists and Nationalists headed by Hitler lacked a majority in the Reichstag. In consequence, Hitler began negotiations with the Center Party with a view to obtaining Catholic support. When, however, Centrists submitted a series of questions regarding Hitler's program, he broke off relations in a huff and asked Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag. Elections for both Reichstag and the Prussian Diet were set for 5 March, although the decision regarding the Diet seemed in violation of the previous decision of the Supreme Court.

The campaign that ensued was one of terrorism conducted by the Nazis against the other parties. It soon became apparent that the Nazis and Nationalists were working hand-in-hand in the government. Through their control of the police, the Nazis were able to pursue their violent tactics unopposed. Hitler persuaded Hindenburg to issue decrees suspending civil rights and imposing severe penalties for political crimes. Terrorist tactics were used to break up the Communist Party and labor union organizations. Unsure of their popular support in spite of a huge campaign of propaganda, Nazi leaders endeavored to inflame public opinion against the radicals by instigating the burning of the Reichstag building and accusing the Communists of the deed. On the strength of this, the Nazis secured the total suppression of Communist and Socialist campaign meetings and press. Communist party leaders were arrested. Even more drastic was the decree of 28 February 1933, which set aside all provisions of the Constitution guaranteeing private rights. Drastic penalties were invoked against violators and the police were given summary powers to enforce them. In spite of the tremendous advantages in their favor, however, the National Socialists obtained only about 44% of the popular vote in the March elections. With the 8% of the Nationalists, their close allies, however, they commanded a total of 52% of the popular vote and won 340 of the 647 seats in the Reichstag. Fearful of the opposition because he had such a narrow majority, Hitler ousted the Communist deputies and reduced the number of Socialists in the Chamber through arrests upon specious pretexts. Warnings and other forms of intimidation were practiced on members of the other parties. It was by means of these unconstitutional procedures that Hitler forced the Enabling Act of 24 March 1933, through the Reichstag.

This law, amplified and substantiated by subsequent legislation, in effect turned over the lawmaking power of the Reichstag in toto to the Hitler Cabinet. Under its provisions, the Reichstag was allowed to continue as a mere shadow of its former self, having no real function except to act as a sounding-board for Hitler's speeches. The position and powers of the president were guaranteed and the Reichsrat was to be continued. These promises, however, were soon violated. On the death of Hindenburg, Hitler made himself both Chancellor and Reich president. The Reichsrat was later abolished. Although the Constitution had not been formally overturned, in effect it had become a dead letter. With all powers concentrated in the Führer, the Reichsrat eradicated, the Reichstag reduced to a non-entity, and all private rights set aside, the democratic principles upon which the Weimar regime had been founded were no more, and dictatorship and the Brown terror took their place.

Hitler and his supporters proceeded with dispatch to strengthen their hold on power. The technique of fear and intimidation of the masses was employed on a wide scale. Nazi terrorist tactics, which had immobilized their opponents during the election campaign, were intensified after the election and followed up by a general attack upon the Jews. On 12 March, Hitler ordered the Storm Troops to cease their vengeance attacks upon radicals and Jews but on 28 March, Nazi headquarters announced a national boycott against Jews in business and the professions on the grounds that German Jews in exile were traducing the German people in foreign countries. Because of the flood of protests against this action from abroad, the Government intervened and limited the boycott to one day only. The passions released among the Brown Shirts and other party formations by this government-sponsored program, however, resulted in continued violence against Jews and radicals for some time afterwards.

The centers of opposition to the party dictatorship were speedily demolished. All dissident parties were either legally abolished or forced to dissolve by their own action. Labor unions and fraternal bodies, such as the Masonic Order, were ordered disbanded. All newspapers and other channels of communication were brought under strict censorship. Policies advocated by the left-wing of the Nazi Party to destroy the "tyranny" of Versailles, curb the great corporations, redistribute the land, and eliminate unemployment, were used to convince the people of the liberal intentions of the "New Order." The terror against Jews and Communists was instituted to divert public attention and give the Nazis a scapegoat on which to blame their own lawless actions. Bodies representative of public opinion, including state, provincial, and local legislatures, were eliminated, and dictator-appointed representatives sent to replace them. Plans were made to bring the Churches under control so that they could be used to help induce conformity to the Nazi program. Thus, German fascism was much more thorough-going in its attempts to achieve the totalitarian state than its Italian prototype.

The National Socialist Party

Origin

The amazing success of the Nazi revolution was due in large part to the work of the National Socialist Party, and some attention to that movement must now be given in order to gain a better conception of its place in the pattern of events. The NSDAP had its origin in the early efforts of the Army and irreconcilable Nationalists to overthrow the Weimar Republic. The German Workers Party organized by Drexler in January 1919 was pro-labor at first, but the direction of its policies was soon changed by the addition to its ranks of large numbers of ex-service men, particularly officers, who had been thoroughly indoctrinated in nationalist ideology and passionately desired Germany's restoration as the greatest power in Europe. In July 1919, Adolf Hitler, an ex-serviceman and house painter, seeking means of overcoming his frustrated ambitions, joined the party and became the seventh member of the party committee. Hitler's abilities as a public speaker and agitator attracted public support and greatly stimulated the party's growth. Rabidly anti-unionist and anti-Marxist from his youth, Hitler became an ardent nationalist after the war. Hatred of the Jews and Communists whom he identified as enemies of Germany's national life, and of the Churches which preached doctrines of pacifism and non-resistance, be came an obsession with him.

After failure of the Kapp putsch in 1920, Hitler was elected president of the German Workers Party. His study of Allied propaganda methods during World War I and his application of them in party campaigns, as well as his skillful management of the party, augmented its strength. Negotiations with the Free Corps, later renamed the Storm Troopers, under Göring's leadership, resulted in an alliance, and plans were made for another attempt at a coup d'état. The insurrection was launched at Munich on 9 November 1923, but was crushed by loyal Republican troops, and Hitler was imprisoned. Defeat of the Beerhall putsch demonstrated to Hitler that the Republic could not be overthrown as long as the masses of the people and the bulk of the army remained loyal. In consequence, he directed his efforts in later years toward winning support of the Army and, in particular, the General Staff, whose purposes he recognized were basically the same as his own. With the cooperation of influential Army officers, he devised new and more effective terroristic methods. Employed by groups privately raised and armed, these revolutionary propagandist techniques, copied from the Bolsheviks and the Allies, could be undertaken under the forms of law with maximum effect.

Hitler's release from prison, where he had spent his time writing Mein Kampf (My Struggle), saw the German Workers Party disunited and on the verge of dissolution. Hence, Hitler decided to start afresh with a new party originated by himself and under his direction but with the aid of many of his old associates. Eager to support a movement which might bring the threat of communism to an end, several great industrial leaders furnished Hitler with ample funds while Army officers aided him in organizing Brown Shirt contingents, and the Elite Guard, a specially selected unit chosen to act as Hitler's bodyguard. Though nationalistic sentiment had risen steadily during the 1920s, it was still in a small minority until the advent of the great depression in 1929 induced many middle-class people to shift their votes to Hitler. To these were added many farmers, war veterans, and doubtful nationalists and militarists, who swung over to the National Socialist side and made it one of the major parties. Hitler's appeals to revenge the defeat of 1918, the disgrace of the Versailles Treaty, and the feeble policies of the Weimar regime in dealing with large-scale unemployment were also effective in converting many youths, students, professional men, and businessmen to his cause.

Hitler's complete victory in March 1933, and his subsequent establishment of a dictatorial regime could not be made permanent without the full consent and cooperation of the Army General Staff. This was made clear later in the year when friction between Brown Shirt leaders and the high command of the regular Army reached disconcerting heights. Undercover negotiations ensued in which Hitler agreed to rid the party and the Brown Shirts of its radical elements in exchange for Army support. The agreement was duly carried out in the blood purge of 30 June 1934, when several hundred subordinates of Hitler, including Captain Ernst Roehm, leader of the anti-Hitler elements sin the Brown Shirts, were assassinated. By this brutal act, a close alliance of Army and Party was insured, and Hitler's security against internal Party dissension was safeguarded. Removal of Army opposition left Hitler unimpeded in his drive to achieve totalitarian unity within and pursue his external objective of conquest of Europe and the world. The elimination of the left-wing leaders, however, gave the Party an orientation still further to the right.

Organization of the Party

In imitation of the one-party systems of Italy and Soviet Russia, Nazi leaders endeavored to maintain loyalty and discipline by frequent purges, but admission to the Party was more akin to the Italian than the Russian model. The pyramidal form of the organization, with Hitler as supreme leader at the top of the pile, was admirably conceived for purposes of concentrated control and singleness of purpose. Attached to the Führer's office was a party chancellery through which all routine business passed. Hitler's chief subordinates consisted of a deputy leader aided by a staff of four members, whose duty it was to supervise Party affairs under Hitler's direction. A nineteen-member Party cabinet advised the principal leaders and, in their capacities as heads of various Party agencies, managed the affairs of the Party. Regionally, the Party organization was based upon the thirty-two Gaue or districts into which Germany was divided. District leaders were subordinate to Party headquarters and the entire system took its orders from Hitler.

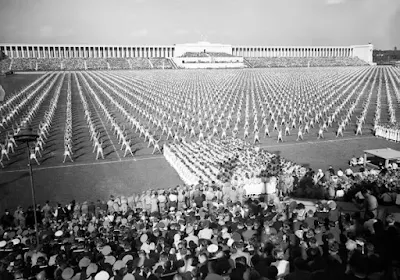

At Berlin, Munich, and other principal Party seats, elaborate quarters were maintained in which the officers and their staffs, and Party military formations were housed. A number of auxiliary associations added strength to the Party. These included professional people, public officials, teachers, and the German Labor Front. Women's and youth's groups were included in the Party hierarchy. Annual congresses held at Nuremberg helped to keep alive the spirit of the Party.

Relation of the Party to the State

In July 1933, all competing parties were legally dissolved and it was made unlawful to form new political parties. Party and State were integrated into closer unity by an act of 1 December 1933. Under this law, the Party was said to be the "bearer" of the German Government and an inseparable part of it. As the "leading and moving power of the National Socialist State," the Party gained a unique place in affairs and its members were given a special status in relation to the law, the courts, and the police. Public officials were required to cooperate with Party members and Storm Troops in the performance of their duties. The Party and its affiliates were declared to be a "corporation of public law," with its members removed from the jurisdiction of the penal courts and placed under Party rules enforced by special Party courts. Though the logical relationships established by the law were by no means clear, the purport of the statue was to make the Party independent of political control because it was above the law and in a position to issue orders to all government officials. Hitler, because of his position as absolute head of the Party, thus became master of the government even if he had not made himself head of the executive as well. Occupancy of all principal government positions by Party members gave assurance that the Führer's orders were to be carried out.

National Socialist Doctrines

Unlike the Italian fascists, Nazi theorists had ample time before the Party took power to formulate a body of doctrines fairly convincing to the German mind. Their principal apologists, E. R. Huber, F. A. Beck, and Arthur Rosenberg, created little that was original, obtaining their ideas in large part from idealists, race theorists, biologists, and economists of the 19th century such as Herder, Hegel, von Humboldt, List, Gobineau, H. S. Chamberlain, and others. Cleverly selecting ideas generally accepted by the German masses, these writers gave powerful aid to the expansionist aims of Germany, and the desire of the people for efficient political leadership and strong government. Among their most important doctrines may be listed:

The Doctrine of the "Folk"

Nazism based its theory of organic nationalism upon a blood relationship rather than upon a spiritual unity of the people. To the Nazis the "Folk" (National Community) is the basic human entity whose members are linked together in blood brotherhood (tribal concept). Out of the "Folk" emerges the State which functions as an instrumentality for securing the ends of the "Folk." A product of emergent evolution based upon race, soil, and cultural changes, the "Folk" has a single will and is aware of its solidarity of purpose. The blood link makes all Germans everywhere a part of the German "Folk" regard less of their legal membership in other states.

The Principle of Racial Supremacy

According to the Nazi doctrine, races vary greatly in their native capacities and adaptability to modern culture. These natural distinctions necessitate the assigning to each race its place according to its capacities. All indications, Nazi writers assert, point to the Aryan race as the master race. Among all Aryans, the Germans are the most intelligent, efficient, and culturally superior. Other Aryan races may be classed as associates but non-Aryans are definitely inferior and should be prohibited from inter-marrying with Aryan stock. Racial inferiors should be relegated to their proper status by law if residing within Germany. Those inhabiting territory needed by the master race for lebensraum should be destroyed or subjected to the will of their racial superiors. Of all non-Aryans, the Jews were looked upon as the lowest and most despicable, good only for deportation, degradation, or slaughter. The race theory was designed by Nazi apologists to nullify the Marxian theory of world brotherhood of the workers while the attack upon the Jews was intended to shift working-class hatred for the employers to the Jews. programs against Jews were also used to justify German expansion into so-called Jewish-dominated states and National Socialist attacks upon the Christian Churches whose creeds were drawn from Jewish sources.

The Leadership Principle

The Nazi doctrine of a supreme leader conformed to German traditional ideas. Dictatorship was rationalized by making the Führer the living embodiment and expression of the basic aims and purposes of "Folk." His declarations expressed the will of the "Folk" and, hence, were always right and entitled to unquestioning obedience.

The Principle of Hierarchy

In the Nazi ideology, political society must be organized hierarchically with the leader at the top, and descends through various levels of authority until the masses of the people are reached. This idea, too, was in accord with German ideas of strong and orderly government. Both Army and civilians readily accepted the idea which, when implemented in fact, gave the Nazis an unbreakable hold on power.

The Principle of an Elite

Nazi doctrine sponsored a trinity of people, Party, and leader or, functionally speaking, supporting class, leading class, and creative class. In this three-fold relationship, the Party furnishes the connecting link between people and leader. In theory selected for their loyalty and devotion to the Party cause, members of the Party were required to demonstrate zeal for their task and unquestioning obedience to the leader. The two principal functions of the Party were to (1) furnish political leadership, and (2) regiment the masses behind the leaders. As rationalized by Nazi spokesmen this meant promoting in the people an interest in political affairs, teaching the principles of Nazism, and securing full support for the purposes of the "Folk" as stated by Hitler. The importance of these tasks explains why the Party was placed above and independent of the state and yet able to direct it into proper channels.

The State as a Total Unity

Hierarchy, in Nazi thinking, was not enough. The state must be organized in such a way as to achieve a total effort carried to the point of maximum efficiency. This meant the removal of all hindrances, the subordination of all political, economic, and social categories within the state and the organization of the state as a total unity to secure the ends proclaimed by the leader. After the Nazi revolution, Hitler decided himself to securing this totalitarian state in preparation for the larger objectives to come later.

The Ends of the State

These were for Nazi purposes adequately expressed under the broad term of welfare of the "Folk." This included, however, social and economic well-being to be secured through proper utilization of resources immediately available and expansion of territory to permit securing of additional resources, thus permitting a rise in the standard of living. This doctrine definitely stated the Nazi purpose to seize territory of the neighbors of Germany. The justification for it could be found not only in the welfare doctrine but in the doctrines of racial and cultural superiority. However, Nazi aims did not stop with acquisition of adjacent territory. Their goals were conquest of Europe and the world.

The Program of the Party

Strong appeals for mass support based upon promises to secure needs long desired by the people, were put forward enticingly in the Party program. Radical promises were made to redistribute the land of the great landed proprietors among the peasants, relieve the poor of the burden of interest and profits, nationalize the trusts, impose a capital levy on unearned incomes and fortunes swollen as a result of war profits, set up adequate old-age security provisions, and safeguard the interests of the small businessman. The platform, moreover, called for abolition of the Versailles Treaty, degradation of the Jews, expulsion of aliens, and conceding of equality of rights and duties for all citizens. Put forth as bait to attract votes, very few of these promises were ever made good. On the contrary, the large landed estates were left intact, the workers were deprived of their freedom, and the great corporations became more powerful than ever.

Government Institutions Under National Socialism Legal Basis

In legal form, at any rate, Hitler could claim that his regime rested upon the existing constitution. Hitler's appointment as Chancellor by Hindenburg made his position legal. The Enabling Act, which was later passed giving the leader and his cabinet extraordinary law-making powers, was duly enacted by the Reichstag in conformity with constitutional procedure. This was true, also, of the act passed after Hindenburg's death unifying the offices of Chancellor and Reich President.

In fact, however, the spirit of the constitution was brutally violated. Transfer of all powers to the cabinet in effect set aside the constitution and made the will of the Chancellor the absolute law of the land. Hitler's powers were dictatorial in extent and became more so as time went on. All political power was vested in him. In theory, Hitler was the sole interpreter of the national will and the only one who "knew the way." Equipped with this awe-inspiring function, the Führer could command absolute obedience from all Germans. This was even more true of Hitler's relation to the Party, whose members had sworn implicit loyalty to him under threats of severe penalties for breaches of discipline. As head of the Cabinet and in a position to secure obedience from its members, Hitler had final authority over all law- and decree-making and as both Reich President and Chancellor, he directed the vast machinery of the Army, the bureaucracy, the police, and local government. These powers were self-expanding since the dictator's authority to increase his own prerogatives were unlimited and were constantly added to until, as the war neared its end, powers of life and death over all citizens and the right to seize private property were conferred upon him.

The Office of the Führer

Not even the check of a definite term of office was set up as a safeguard against the delegation of these vast powers to the Führer. Presumably his term was for life, although his powers were extended from time to time. The leader appointed his own successor. Needless to say, the conferring of such vast powers upon one man did not mean in fact that he could exercise them in detail. In practice, Hitler, who hated the routine handling of government affairs, left the details to his subordinates and confined his own work to occasional intervention to adjust mistakes or prevent conflicts between administrators. This left Hitler free to concentrate upon military affairs and foreign policy in which he prided himself on his proficiency. His confidence in himself seemed to be borne out by his singular diplomatic triumphs between 1933 and 1939, which, together with his military victories in 1940-1941, gave him tremendous popular prestige. His defeats in the Russian campaigns and reversals in the latter stages of the war, however, shattered the myth of his invincibility and turned both the public and the Army against him.

The Führer's Personal Staff

Three important bureaus handled Hitler's personal business. These were the Chancellery of the Reich, the Chancellery of the President, and the Chancellery of the Leader of the Party. The first agency canvassed the news and kept track of legislative proposals emanating from the various ministries. The second office specialized on diplomatic and personnel questions, while the third bureau handled all Party matters needing attention by the leader, as well as economic problems arising in the National Defense Council.

The National Defense Council

Created in August 1939, this body was headed by Göring and included top-ranking officials representing the Party, the Army, and economic affairs. Having as its chief responsibility, the overall planning for the nation's defense, the Council was given broad powers to coordinate civil, political, economic, and military operations to secure this end. Full legislative and executive powers to deal with these matters were delegated to this body by Hitler, and they could be exercised without specific approval from him. Individual members of the Council could issue decrees within their own spheres of action. Defense districts headed by Reich Defense Commissioners were set up throughout the Reich to administer the program in detail.

The Cabinet

The coalition cabinet formed by Hitler under Hindenburg's direction in 1933 was gradually converted through dismissals and new appointments into a completely Nazi organization. The new Ministries of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, Air, Church affairs, and Science and Education were added in 1933-1934. The Ministry of Economics and Agriculture was divided into two separate agencies. By January 1945, fifteen Cabinet Ministries were in existence. These were: Interior, Foreign Affairs, Justice, Propaganda, Economics, Food and Agriculture, Finance, Labor, Education, Church Affairs, Transport, Ports, Air, Armaments, and War.

Added to the cabinet, also, were the Chief of the Reich Chancellery, the Deputy Leader, the Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces, the Delegate in charge of the Four-Year Plan, and other top-ranking officials appointed by Hitler. The Deputy Leader (Rudolph Hess) flew to England in 1942 where he was captured and interned. The Chief of Cabinet of the Deputy Leader (Martin Bormann) was therefore designated to replace him. The Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces became the ministerial representation of all military and naval formations. The Delegate in charge of the Four-Year Plan was chairman of the War Council and, therefore, director of all non-military war activities. Indeed, Göring, by Hitler's command, could issue orders to all departments in respect to matters affecting the war effort.

Under the Nazi regime, the cabinet, as such, lost its controlling position in the government and developed into a mere group of department heads taking orders from an all-powerful dictator. Having lost its corporate power to determine policy and guide administration, the cabinet became an advisory body only. Its deliberative functions were taken over largely by the War Council. Meetings were infrequently held, and Hitler, by consulting ministers individually, caused it to disintegrate still further. On the other hand, Hitler's tendency to delegate power plus the necessities of the case, enabled more capable executives to create powerful personal machines within their departments over which they exercised unquestioned sway. Interdepartmental rivalries between department heads ambitious for power, resulted in ups and downs for various ones with Göring, Goebbels, Ribbentrop, and Himmler fighting it out for precedence. Ultimately Himmler, as head of the Gestapo and the SS Elite Guard, won his way to top place at the end of the war.

The Civil Service

In order to induce the measure of cooperation found lacking in the civil service under the Weimar Government, the party dictatorship launched a thorough-going purge of the government services. Under the act of 7 April 1933, as subsequently amended, all Jewish employees of the government were made subject to demotion or dismissal. Jews were also barred from seeking employment with the government. Jews, Communists, and recent appointees when dismissed were ineligible to receive dismissal ages. The purge of Jews and radicals was applied to all levels of the teaching profession as well as other government positions. In January 1937, new regulations were introduced stipulating five essentials for office-holding:

special preparation for the position.

proven loyalty to the Nazi regime.

Aryan parentage.

performance of required labor and military service.

an oath of allegiance to Hitler.

The drastic legal provisions placed on the statute books did not, however, secure the thorough cleansing desired by the Nazis. The need to retain competent public servants compelled retention of non-Nazis on all levels. More effective at the higher levels, the purge failed to operate effectively in the middle and lower strata of government officials. In consequence, considerable friction developed between party and bureaucracy owing to the independent attitude assumed by the latter.

The National Legislature

As has been noted, the Reichsrat was finally abolished by the Nazi "New Order." This left only the Reichstag, which Hitler was pledged to preserve. True, the Reichstag was continued but stripped of the great powers it possessed under the Republic. Deputies continued to be elected but the elections became a farce. Lists of candidates were prepared by the Nazi Minister of the Interior and no competing candidates were permitted to run. Hence, the people had no choice even if they had been allowed to vote freely. The result was the election of Reichstags composed almost entirely of Nazis. Since all legislative powers had been delegated to the cabinet, the Reichstag had little to do. Consequently, the lower house met infrequently and occupied its time in approving already consummated acts of government or in rubber-stamping some notable achievement of the Führer. Between 1933 and 1938, four elections to the Reichstag were held. Deputies continued to draw their salaries though largely deprived of their functions. Thus the people lost the only remaining vehicle for effectuating popular desires.

Changes in the Judiciary