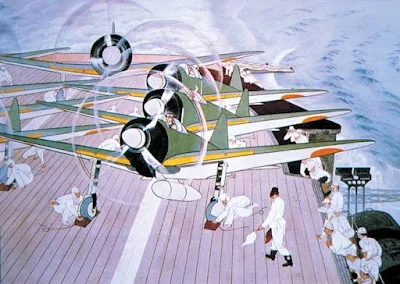

It was early morning, 7 December 1941. As the sun was just

beginning to rise in Oahu, Hawaii, a fleet of Japanese naval air forces were

taking off from their respective aircraft carriers in various locations in the

Pacific Ocean. Just as many of the islanders were waking up for breakfast, it

happened. The Japanese air fleet had arrived with a vengeance. No one was

prepared for what was occurring. Pearl Harbor, the United States’ center for

military action in the Pacific Ocean, was almost completely destroyed. Anger

toward the Japanese spread quickly throughout the entire country, and this

anger led to the United States’ entry into World War II.

Events Leading Up to the Attack

Before entering World War II, Japan had many other problems

to deal with. It had begun to rely more and more for raw materials (especially

oil) from outside sources because their land was so lacking in these. Despite

these difficulties, Japan began to build a successful empire with a solid

industrial foundation and a good army and navy. The military became highly

involved in the government, and this began to get them into trouble. In the

early 1930’s, the Japanese Army had many small, isolated battles with the

Chinese in Manchuria. The Japanese Army prevailed in the series of battles, and

Manchuria became a part of the Japanese political system. In 1937, the

conflicts began again with the Chinese in the area near Beijing’s Marco Polo

Bridge. Whether or not these conflicts began inadvertently or whether they were

planned is unknown. These led to a full-scale war known as the second

Sino-Japanese War. This was one of the bloodiest wars in world history and

continued until the final defeat of Japan in 1945.

In 1939, World War II was beginning with a string of

victories by German forces. Germany’s success included defeats of Poland and

France along with a seizure of England. Many of the European nations that

Germany now controlled had control over important colonial empires such as the

East Indies and Singapore in Southeast Asia. These Southeast Asian countries

contained many of the natural resources that Japan so desperately needed. Now

that these countries were worried about matters over in Europe, Japan felt that

it should seize the opportunity to take over some of them.

At the same time in the United States, President Franklin D.

Roosevelt wanted to halt the expansion of Germany and Japan, but many others in

the government wanted to leave the situation alone. The United States began to

supply materials to the countries at war with Germany and Japan, but it wanted

to remain neutral to prevent an overseas war. Meanwhile, Germany, Italy, and

Japan formed the Axis Alliance in September of 1940. Japan was becoming

desperate for more natural resources. In July of 1941, Japan made the decision

to secure access to the abundance of the much needed resources in Southeast

Asia. It was afraid that it could not defeat the larger and stronger Western

powers. It needed to build up its armies in order to stay in the war. It also

had to worry, though, about the United States’ reaction to their plans to seize

Southeast Asia.

Japan began their seizure with southern Indochina. (They

already controlled northern Indochina.) The United States was in strict

opposition to Japan’s plans, and began their reaction with an embargo on the

shipment of oil to Japan. Oil was necessary to keep Japan’s technology and

military progressing. Without it, Japan’s industrial and military forces would

come to a stop in only a short time. Japan’s government viewed the oil embargo

as an act of war.

Throughout the next few months of 1941, the United States

tried to come to some kind of resolve with Japan to settle their differences.

Japan wanted the United States to lift the oil embargo and allow them to

attempt a of China. The United States refused to lift the embargo until

takeover Japan would back off of their aggression with China. Neither country

would budge on their demands, and war seemed to be inescapable.

The United States regarded Japan’s adamant refusal to budge

on their stance as a sign of hostility. They too realized that war was

inevitable. They responded to this potential war with Japan by adding to the

military forces stationed in the Pacific. General Douglas MacArthur and his ground

forces in the Philippines began to organize into a formidable army. The B-17

was just arriving at many air force bases throughout the country, and was a

great confidence to MacArthur upon its arrival. MacArthur became so confident

in his forces stationed in the Philippines that on 5 December 1941 he said,

“Nothing would please me better than if they would give me three months and

then attack here.”

The most powerful and most crucial part of American defense

in the Pacific Ocean was that of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Usually, this fleet

was stationed somewhere along the west coast of the United States, and made a

training cruise to Hawaii each year. With war looming, the U.S. Pacific Fleet

was moved to the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii. This was the perfect

location for the American forces in the Pacific because of its location,

halfway between the United States west coast and the Japanese military bases in

the Marshall Islands. The Pacific Fleet first arrived at Pearl Harbor naval

base on 2 April 1940, and were scheduled to return to the United States

mainland around 9 May 1940. This plan was drastically changed because of the

increasing activity of Italy in Europe and Japan’s attempt at expansion in

Southeast Asia. President Roosevelt felt that the presence of the Pacific Fleet

in Hawaii would retard any Japanese attempt at a strike on the United States.

Admiral James O. Richardson of the Pacific Fleet was in full opposition to the

long stay at Pearl Harbor. He felt that the facilities were inadequate to

maintain the ships or crews. Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval

Operations, was the one who originally made the decision to extend the crew’s

stay in Hawaii; and, in spite of Admiral Richardson’s complaints, he maintained

that the Pacific Fleet must stay there to keep the Japanese from entering the

East Indies. Richardson felt that the Japanese would realize the military

disadvantages of being stationed at Pearl Harbor, and would be quick to act on

the situation. All of Richardson’s objections, in meetings with both the

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox and the President, got him nothing but a

dismissal shortly thereafter.

On 12 November 1940, British torpedo bombers launched an

attack on the Taranto harbor in Italy. This sent worry into United States government

officials who were afraid that the same thing could happen to Pearl Harbor. On

22 November, Admiral Stark suggested to Richardson the idea of placing

anti-torpedo nets in Pearl Harbor. Richardson replied that they were neither

necessary nor practical. On 1 February 1941, Richardson was officially replaced

by Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. Kimmel also did not like the idea of his fleet at

Pearl Harbor; but, after seeing what had happened to Richardson, he was very

quiet about his objections. The Pacific Fleet was to be used as a defensive

measure to direct Japan’s attention away from Southeast Asia by:

Capturing the Caroline and Marshall

Islands

Disrupting Japanese trade routes,

and

Defending Guam, Hawaii, and the

United States mainland. Kimmel was supposed to prepare his fleet for war with

Japan.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of Japan’s

Combined Fleet, had to be careful of his country’s position in the Pacific. If

he concentrated his forces too much in the Pacific islands, then the mainland

would be more susceptible to attack from Europe and even the United States.

Yamamoto devised a plan that involved an opening blow to the United States

Pacific Fleet at the same time as their offensive against British, American,

and Dutch forces in Southeast Asia. He planned to cripple the United States

while he quickly conquered much of Southeast Asia and gathered their natural

resources. He hoped that his attack against the Pacific Fleet would demoralize

the American forces and get them to sign a peace settlement allowing Japan to

remain as the power in the Pacific. A month after the British attack on Taranto

harbor, Yamamoto decided that if war with the United States was unavoidable he

would launch a carrier attack on Pearl Harbor. In January of 1941, Yamamoto

first began to commit to this strategy by planning out his attack and showing

it to other Japanese officials. Yamamoto developed the following eight

guidelines for the attack:

Surprise was crucial

American aircraft carriers there

should be the primary targets

U.S. aircraft there must be

destroyed to prevent aerial opposition

All Japanese aircraft carriers

available should be used

All types of bombing should be used

in the attack

A strong fighter element should be

included in the attack for air cover for the fleet

Refueling at sea would be

necessary, and

A daylight attack promised best

results, especially in the sunrise hours.

Many of Japan’s Navy General Staff were in opposition to

Yamamoto’s plan, but they continued to prepare for the attack. All of the

necessary training was given to troops, and all of the fighters and submarines

were prepared.

The Bombing Begins

There were peace talks occurring up until about 27 November

1941. At that time, negotiations had come to a halt. The United States put its

troops on alert. On 6 December 1941, President Roosevelt made an appeal for

peace to the Emperor of Japan. Not until late that day did the U.S. decode

thirteen parts of a fourteen part message that presented the possibility of a

Japanese attack. Approximately 9 a.m. (Washington time) on 7 December 1941, the

last part of the fourteen part message was decoded stating a severance of ties

with the United States. An hour later, a message from Japan was decoded as

instructing the Japanese embassy to deliver the fourteen part message at 1 p.m.

(Washington time). The U.S., upon receiving this message sent a commercial

telegraph to Pearl Harbor because radio communication had been down.

At 6 a.m. (Hawaiian time) on 7 December 1941, the first

Japanese attack fleet of 183 planes took off from aircraft carriers 230 miles

north of Oahu. At 7:02 a.m., two Army operators at a radar station on Oahu’s

north shore picked up Japanese fighters approaching on radar. They contacted a

junior officer who disregarded their sighting, thinking that it was B-17

bombers from the United States west coast. The first Japanese bomb was dropped

at 7:55 a.m. on Wheeler Field, eight miles from Pearl Harbor. The crews at

Pearl Harbor were on the decks of their ships for morning colors and the singing

of The Star Spangled Banner. Even though the band was interrupted in their song

by Japanese planes gunfire, the crews did not move until the last note was

sung. The telegraph from Washington had been too late. It arrived at

headquarters in Oahu around noon (Hawaiian time), four long hours after the

first bombs were dropped.

Aftermath of the Bombing

Of the approximately one hundred U.S. Navy ships present in

the harbor that day, eight battleships were damaged with five sunk. Eleven

smaller ships including cruisers and destroyers were also badly damaged. Among

those killed were 2,335 servicemen and 68 civilians. The wounded included 1,178

people. The U.S.S. Arizona was dealt the worst blow of the attack. A 1,760

pound bomb struck it, and the ammunition on board exploded killing 1,177

servicemen. Today, there is a memorial spanning the sunken remains of the

Arizona dedicated to the memory of all those lost in the bombing.

News of the attack was a shock to the entire nation. The bombing

rallied the United States behind the President in declaring war on Japan. On 11

December, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S., bringing about a global

conflict. The United States would later drop two atomic bombs on the Japanese

cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bringing Japan to complete surrender on 14

August 1945.