|

| HMS Walney on fire in Oran harbor during Operation RESERVIST. Painting by Darren Tan. |

by David Rame

Published in 1944

Even in the crowded history of the Royal Navy of Britain there are few entries that match in courage, in endurance, in magnificence the thrust to Oran harbor.

Who conceived that plan, we never learned; who measured its audacity against the weight of the inevitable opposition of the Navy of France, we were never told. All that we knew was that an attack would be made.

Oran harbor is ancient. From the Vieux Port under the shadows of Mourdjadjo and the Fort of the Holy Cross, corsairs of the Barbary coast thrust out their galleys against Christendom. Barbarossa is said to have used it, Mohammed El Kebir sent out his ships from it beyond all question, but like all the ancient harbors it was small, a basin backed on the one side by the slopes of the mountain, fringed to the south by the city wall, penned in with small moles thrust out into the Mediterranean. Today it harbors yachts, tunny-fishing boats, small craft of one sort and another, a peaceful corner of the greater harbor, filled with color.

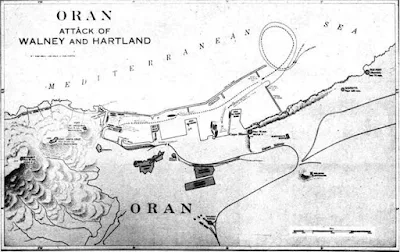

The new harbor is big. From the quay of the Naval barracks in the Bassin Gueydon to the end of the outer mole—the Jetée du Large—is 3,000 yards, almost two miles. From Pointe Mona north of the old city, the outer mole runs parallel with the coast line across the whole face of the town past the Ravin-Blanc and almost to the Batterie de Gambetta. From the old shore moles jut out into the area it encloses: the Môle Bougainville, the Môle Sainte-Marie, the Môle Jules-Giraud, the Môle Millerand, the Môle du Ravin-Blanc. The whole is sealed with the Traverse du Large, a narrow breakwater towards the seaward end of which is the single entrance to the harbor.

That entrance was protected by a double boom.

Immediately over the port and for its further protection were the batteries of Saint-Grégoire, Fort Lamoune, RavinBlanc, and Gambetta.

On its quays were heavy machine guns.

Alongside them was the contratorpilleur Epervier, a small light cruiser or very large destroyer of the "Aigle" class—2,400 tons, 36 knots, five 5.5-inch guns, six torpedo tubes. Close to her lay at least two other destroyers (according to some accounts three), four submarines, and mine sweepers and other small naval craft.

Against that concentration of ships and guns, into that narrow cul de sac of fire, we threw two Coast Guard cutters HMS Walney and HMS Hartland.

Walney and Hartland came to England with the fifty Lease-Lend destroyers in the bitter days when every ship that Britain could muster could not make up the total that was necessary to fight the U-boat.

They were ships of peace, police of the Western Ocean. Every voyager along the eastern seaboard of the United States was familiar with them: small, chunky ships with high bows and high, square superstructures amidships, and straight-up-and-down smokestacks; not beautiful but infinitely useful in their work of keeping the law along the edges of the ocean, watching the icebergs of the danger areas, shepherding the foolish, and aiding the battered. They were not meant for war, but they have done in this war a great work against the submarine.

Walney and Hartland came with us all the way. We grew to know their silhouettes day after day along the horizon as they steamed in the line that over the long voyage kept us safe from torpedoes of the enemy. One of them on the very last day of the passage picked up a man of ours who had jumped over the side. We were almost friendly with them, and the last time we saw them they were still with us, still just a little astern of us in the twilight, with MLs attendant on them. Sometime in the darkness they broke away.

The first of their story I saw myself, saw in the distant flickering of the gun flashes over Oran. I saw them, but I could not translate in its entirety their meaning. I heard of them next in the courtyard of the Château-Neuf when, in between the talking of the generals, the French interpreter whispered to me that there had been a terrible battle in the harbor. He had watched it from the heights. Two ships, he said, had broken the boom and steamed into the harbor; a searchlight had picked them up—there was an explosion. "Terrible, terrible. They came out of the water like Negroes," he said, and repeated it again and again, "like Negroes." I added a fragment to that mosaic when Captain Peters came, patch over eye like a sad buccaneer, his face seamed and lined still with the strain of that night.

And then the next day I found on the steps of the Grand Hotel, that had become American Headquarters in Oran, a little group of lost and battered souls who wore fragments of the insignia of naval officers. They were bearded, and they told me they were bug-infested. They had come straight from prison.

I took them up to my room and gave them razors and soap and towels, and while they shaved and bathed they told me haltingly, and in the tongue-tied jargon of the naval officer, something of their story. More I got from two of them who went with me down to the harbor the next morning; more still I got from Hartland's captain, lying in hospital.

I wish I could convey something of the excitement in which that story grew. Something of the atmosphere of greatness that rose about it as fragment after fragment was fitted into the mosaic. Something of the sense of splendor that enveloped it.

HMS Walney broke the Oran boom at ten minutes past three on the morning of "H" Day.

Closing the coast near Canastel, Walney with Hartland and two MLs moved silently in towards the objective. Despite their precautions it is almost certain that the little flotilla was sighted in the early minutes of the moment. The water was brilliant with phosphorescence, and they moved in a trail of green fire which almost certainly must have been visible to watchers on the coast. And there were watchers on the coast. Already we had landed at Arzeu and the Rangers had reached the Fort du Nord. We had landed at Bou Zadjar and at Les Andalouses as well. The carriers of the parachute attack had crossed the coast. All along the shore the batteries must have been on the alert.

Yet from them there was no sign. Walney in the lead passed Canastel, came in under the shadow of the cliffs of Gambetta (where the batteries could have smashed her at close range), came up to the round bull nose of the Jetée du Large; and from her bridge Captain Peters and Lieutenant Commander Merrick sighted the floats of the boom. They were five hundred yards from the shore line now, headed straight for the gap between the walls. Working up to full speed, they crashed into the heavy line of floats—Walney's bows were specially strengthened for the winter ice along the coast of Maine—they went through the double boom "Like a wire through cheese," one of the subs told me.

And no shot was fired from the shore.

Walney went on. In a strange, formidable silence she penetrated into the Avant-Port, passed the end of the broad Môle du Ravin-Blanc, crossed the Bassin-Poincaré, and moved to the Bassin du Maroc—and still the guns were silent.

Clear of that, almost a mile and a half inside the silent docks, she sighted a destroyer coming out of the naval harbor and attempted to ram. Before she made position heavy machine guns opened fire from the breakwater and from the quays. Instantly the night went mad about them. Searchlights down the quay broke out, licked by them in white flame, and blazed across the harbor; tracer bullets raked the darkness with brilliant fire; the glare of gun flashes split the night. They grazed past the French destroyer, unable to make their turn swiftly enough to ram into the crowded confines of the harbor, and swept into the Bassin Gueydon, the last basin of them all.

Their objective was the Môle Bougainville. Their orders were to lay themselves alongside the Quai Central, and land their attacking force. In her mess decks Walney carried more than two hundred men of the Third Battalion of the 6th Armoured Regiment. Their mission was to take the port offices—a high modern building on the end of the mole. From there they hoped to prevent sabotage, to stop the scuttling of ships, to control their end of the harbor.

They never landed.

At the end of the Quai Central, in the berth that was their objective lay the light cruiser Epervier, her guns ready. In the Bassin over the northern side the submarines were putting to sea with their guns ready also. Mine sweepers, the other destroyers, the batteries had come into this fury of action. Shells were hitting Walney fast now, communication with her after guns had gone already, men were dead about their breaches, and in the hell of the mess decks the shells were ripping through the sides like paper and exploding among the helpless soldiers.

They might perhaps have turned and run for it. They might have ceased fire and hauled down their flag. They might have sought shelter against the wall of the Môle Giraud and hoped for quarter. But they went on. Their objective was the Quai Central, and alongside the Quai Central lay the Epervier—they made their course to lay themselves alongside her.

Shells and machine gun bullets killed off the crew of the after gun. Lieutenant Moseley told me, "I found myself trying to give orders to dead men." Somehow the guns were manned again. They were getting in their own hits too. One point-five machine gun after another was silenced, they shot out the searchlight, they battered a destroyer over close to the Naval Barracks so that she sank at her moorings. But they were hacked through and through, the mess decks were an unholy shambles of blood and of dead men; their communications were gone; their speed was falling as the steam pipes went; their decks were twisted and torn with high explosive.

Broken and battered as they were, they laid themselves alongside the Epervier.

"We meant to board her with Tommy guns," said one of her officers. "We had a chance, you know. Hardly any ships carry enough small arms."

They got grapnels onto her and made them fast, but there was no steam for the capstans—the pipes were shot away. There were no men to man the ropes. The gun crews were in sober fact blown over the side not by shells but by the blast of the Epervier's guns.

The ropes were severed, and, very slowly, her boilers hit and her engine room wrecked, the Walney fell away.

Commander Merrick was dead; so were most of her officers. Captain Peters was wounded. Lieutenant Colonel Marshall was killed. Walney was a ship of the dead.

And down the harbor Hartland was fighting out her battle. Coming in astern of Walney, Lieutenant Commander Billot, RNR, her captain, headed for the gap that the leader had made. Between her and Walney was an ML laying a smoke screen. In the darkness and the blindness of the smoke they reached a point a hundred yards from the broken boom. The batteries of Gambetta and Ravin-Blanc were firing now, shell splashes leapt crazily in the glare of searchlights or showed luminous against the smoke. It is not clear even now what happened, but the ML, probably hit in her steering gear, swung suddenly from her course and lay square across the Hartland's bows. In the fractional second of decision Commander Billot swung his ship away, but the ML was still moving. They crashed through her as they swung, and she sank in halves on either side of them. The Hartland was too far off her course now, and Billot swung her clear round in a circle outside the line of the Jetée du Large—always the target of everything that would bear—brought her back on her course, and approached the gap for a second time.

The Hartland was hit already, badly hit; but he took her through, fighting back at every gun flash that his fire control could locate, took her across the Avant-Port, made the Môle du Ravin-Blanc, swung round it, and reached objective. His controls were shot away now, his communications gone; but somehow he brought his ship alongside, somehow they got lines out; and then, as with Walney the last tragedy overwhelmed them, there were no men left on deck alive to man the lines. On fire, her ammunition exploding, her engines dead, her controls gone, Hartland drifted away with the wind, and as a last desperate measure Billot, already wounded, gave the order to drop the anchor.

She lay there in the open basin shelterless in the glare of the pitiless lights. And in the open she died.

"But," said Commander Billot, "I never hauled down my flag."

There is no end to the stories of gallantry in the rescues. No end to the individual hardihood. Bill Disher of the Exchange Telegraph, the only journalist with the expedition, swam wounded through a storm of machine gun fire, reached safety, and was wounded again; men paddled their way through the scum of oil on the water and were hauled up the sides of the Epervier, one small group swam until they found a rowboat tied to the quay and then, themselves in safety, turned her round and, paddling with the floorboards because she had no oars, worked her out in the hell of the basin again to pick up Billot and other survivors. It was that same boatload that sat there under fire and solemnly debated the chances of paddling her out to sea and getting away—and half of them were desperately wounded.

Hartland was a blazing torch on the calm water. Billot had ordered her abandonment shortly after he dropped anchor, yet her first lieutenant told me that man after man came to him and said, "Does that mean we've got to abandon ship, sir?"

They thought the order was for the soldiers.

But the real tragedy of the operation was the tragedy of the Sixth. Penned in the terrible mess decks, the thin steel of the sides like paper against the shells, they died not in ones, not in tens, but in scores. When Hartland blew up in thunder at ten o'clock under the hot sun, she took with her one hundred and seventy men.

Walney at the other end of the harbor, riddled and with her boilers gone, sank with as many, and as her survivors escaped on Carley floats, on rafts, on wreckage, they were run down by the French destroyers and the submarines, putting to sea. More than two hundred men were lost with her.

The operation ended in failure. But was ever failure more gallant, was ever tragedy made more splendid by the courage and the sacrifice of men?

They died, but their epitaph shall read, "They reached objective!"

|

| Attack of the Walney and Hartland. |

|

| Oran, looking northwest. Symbol (1) indicates limit of penetration of HMS Walney and (2) of HMS Hartland. |

|

| Entrance to Oran Harbor. The port entrance is visible in the upper center of this photograph, taken six months later. |

|

| Oran harbor. |

|

| HMS Hartland. |

|

| HMS Hartland on fire and sinking after following HMS Walney into Oran Harbor. |

|

| HMS Hartland on fire and sinking after following HMS Walney into Oran Harbor. |

|

| HMS Hartland on fire and sinking after following HMS Walney into Oran Harbor. |

|

| The "VC" ship, HMS Walney, sunk in harbor, Oran and Mers-el-Kebir, 22 and 23 November 1942. |

|

| The "VC" ship, HMS Walney, sunk in harbor, Oran and Mers-el-Kebir, 22 and 23 November 1942. |

|

| Oran Harbor and Mers-el-Kebir, 22 and 23 November 1942. |

|

| The Royal Navy on anti-submarine patrol around Oran. photographs taken from HMS Formidable, 19-21 November 1942. The French fort on top of the hill, west of Oran, Oran Harbor and town. |

|

| A French fort near Oran which is now in Allied hands. |

|

| The Royal Navy on anti-submarine patrol around Oran. Photograph taken from HMS Formidable, 19-21 November 1942. A destroyer and auxiliary aircraft carrier off Oran. |

|

| Anti-submarine patrol aboard HMT Stoke City, November 1942. The Captain - a Lieutenant RNR. |

|

| United Press advertisement in Broadcasting magazine, 1942. |