|

| American Liberty Ship SS Stephen Hopkins. Last Stand of the SS Stephen Hopkins. Painting by John Alan Hamilton (1919–1993). (Imperial War Museum) |

On Sunday morning, 27 September 1942, the German raider Stier and blockade runner Tannenfels were awaiting a rendezvous with a tanker. Suddenly a ship emerged from a rain squall. She was an American Liberty ship, the Stephen Hopkins. However, the German vessels did not know her name. The captain of the ship, Paul Buck, thought them to be harmless freighters but upon close examination through his glasses, he spotted big guns on the lead ship and went to a General Alarm.

The captain of the Stier, Franz Gerlach, considered her another defenseless target. The Stier (ex-merchant vessel Cairo, HSK 6, ship number Schiff 23 [for signal purposes], Raider J) was armed with six 5.9-inch guns, two 37-mm anti-aircraft guns, four 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, and two 21-inch torpedo tubes (submerged). She also carried two aircraft, and could make 14 knots. Her previous successes were the Gemstone, Stanvac Calcutta, and the Dalhousie. The Tannenfels withdrew, her captain certain that the Stier could sink the Liberty ship in matter of minutes. This seemed a certainty when considering the green crew and the single 4-inch gun on her stern.

The Stier opened fire at a thousand yards scoring a hit immediately amidships. Another shell exploded in the engine room.

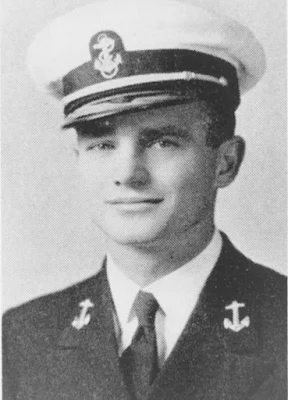

Captain Buck turned the Stephen Hopkins to port to bring the gun to bear on the raider. Captain Gerlach turned his ship to starboard to cut her off. As Ensign Kenneth Willett, the captain of the Navy gun crew, reached the boat deck on his way to the gun he was wounded in the stomach by shrapnel. Some of the crew helped him to his gun where he managed to direct fire at the Stier. The Stier was hit twice as she completed her turn, the first jamming the helm to starboard so that she now only could turn in a circle. The second exploded in the main engine room and severed oil lines to the Stier's engines.

Both ships pounded each other for the next ten minutes, the Stier taking fifteen hits—the Hopkins fast becoming a slaughterhouse, her decks littered with the dead and wounded of her crew. Below, more dead, mostly from the many fires that raged, or choking to death from the smoke or cordite fumes.

Ten minutes later Captain Buck ordered abandon ship but he was not heard as the communications were long gone. Each member of the crew fought his own battle, with the raider and for his life.

Only one lifeboat was in a seaworthy condition. As the boat was being lowered Cadet Edwin O'Hara looked around and saw the gun unmanned. He raced back and began to fire the five remaining shells by himself. The Tannenfels had returned and began to fire. As O'Hara fired the last round the German shells found their mark.

Second Engineer George Cronk and eighteen others escaped in the lifeboat. Four died on their journey towards the Brazilian coast, some 2,000 miles distant.

The Stier was practically an inferno and Captain Gerlach gave the order to abandon ship. German casualties were four killed and thirty wounded. Most of the crew were picked up by the Tannenfels. Later the Stier blew apart with a tremendous explosion.

The Tannenfels searched for survivors of the Hopkins. They found none and circled the spot where she went down, flag at half-mast as a final tribute.

The fifteen survivors in the lifeboat reached shore near Rio de Janeiro on 27 October, precisely one month after the battle.

So rapid and destructive was the fire of the Hopkins that Gerlach thought it carried four or five guns and that he had engaged an auxiliary warship, patrol vessel or even an armored cruiser.

Action of 6 June 1942

The action of 6 June 1942 was a single ship action fought during World War II. The German raider Stier encountered and sank the American tanker SS Stanvac Calcutta while cruising in the South Atlantic Ocean off Brazil.

Background

Stanvac Calcutta was a 10,170 ton tanker with a crew of forty-two merchant mariners and nine armed guards aboard. The ship was commanded by Gustav O. Karlsson and the guards by Ensign Edward L. Anderson. Throughout World War II merchant ships were lightly armed and out of the six to be attacked by German raiders, only Stanvac Calcutta and Stephen Hopkins offered serious resistance and both were sunk. When Ensign Anderson was assigned to the ship he was responsible for finding armaments and it proved to be difficult. Anderson acquired one 4-inch (102 mm)/50-caliber naval gun salvaged from World War I and an 5 in (127 mm)/25-caliber anti-aircraft gun from the same era to arm his ship. Stier was heavily armed, she was under the command of Captain Horst Gerlach and mounted six 150-millimeter (6 in) guns, one 37 mm (1.5 in) gun, two 20 mm (0.79 in) cannons and two torpedo tubes. Captain Karlsson left Montevideo on 29 May 1942 headed north along the coast for Caripito, Venezuela.

Action

A week after leaving Montevideo at 10:12 am on 6 June, the American ship was 500 miles (800 km) east of Pernambuco, Brazil; weather was overcast and the sea rough. Suddenly gunfire was heard and the Americans observed Stier sailing out of a squall and quickly heading towards Stanvac Calcutta almost head on and signaling the Americans to cut their engines. The Germans apparently believed the tanker was an unarmed merchantman. Beforehand Captain Karlsson and Ensign Anderson had planned a course of action for defending the vessel. As soon as the Germans were spotted, Stanvac Calcutta turned to the side to bring her guns to bear and when the raider closed to an estimated 3,500 yards (3,200 m), Ensign Anderson ordered his gunners to open fire. In succession the armed guards fired five shots with the aft 4-inch gun and several rounds of the bow anti-aircraft gun. The last of the five shells struck and disabled a 150 mm gun aboard Stier just before it began delivering broadsides of four cannons and machine gun fire.

Merchant sailors were trained and used to man the anti-aircraft gun; it fired continually throughout the battle though it misfired a few times because of old ammunition. In fifteen minutes of fighting, the Stanvac Calcutta was struck several times in the bridge and elsewhere, killing Captain Karlsson and a few other men. After hitting the Stier, the guards manning the 4-inch gun were reported to have been encouraged and continued firing accurately until shrapnel damaged their weapon. The sights were destroyed but the Americans continued shooting until the ammunition on deck was exhausted. At this time Ensign Anderson ordered two men to retrieve more ammunition from below deck, though as soon as they left, Captain Gerlach maneuvered his ship for a torpedo attack. When lined up, Stier fired one torpedo and it dove into the water and headed straight for Stanvac Calcutta where it detonated on the port side. Water began flowing in and the vessel started listing. A number of additional men were killed in the torpedo explosion and when it was clear that the American ship could not be saved, Ensign Anderson ordered the survivors to abandon ship and he began to lower life rafts.

While operating the crank, Anderson was hit in the back by a piece of shrapnel, paralyzing his legs, but he continued to lower the boat and after looking around to see if anybody else needed help, the ensign slipped over the side into an oil slick. With a broken leg, Anderson swam over to a wounded officer in the water and attempted to pull him to one of the life rafts but the man died of his wound first, and a few moments later the Germans lowered boats and began rescuing the Americans. The Germans fired 148 shells and one torpedo while Stanvac Calcutta fired only twenty-five; hundreds of machine gun rounds were also expended by both sides.

Aftermath

Sixteen merchant sailors and armed guards were killed in action, thirty-seven prisoners were taken, of whom fourteen were wounded, one armed guard died later aboard Stier. Two Germans were wounded and Stier continued raiding for four months, sinking only two more ships before being sunk by Stephen Hopkins in a mutually-destructive battle. SS Stanvac Calcutta was one of the few World War II merchant ships to be awarded the Merchant Marine Gallant Ship Citation. Ensign Anderson was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander before leaving the navy sometime after the war. The American prisoners were eventually turned over to the Japanese.

Gallant Ship Award Citation

When about 500 miles off the coast of Brazil she was attacked by a heavily armed raider which came up close on her in a heavy squall. Though armed with only a 4″ rifle aft and a 3″ antiaircraft gun the ship tried to escape in a running fight. On the 5th round fired, the STANVAC CALCUTTA knocked out one of the raiders 15 cm guns but the next round from the enemy guns shattered the pointers scope and sight bar. The crew continued to fight the gun by laying without signs until the ammunition magazine was hit and the ship began to sink. With fourteen dead and fourteen seriously injured, the crew was forced to abandon ship and were taken prisoners.

This heroic defense against overwhelming odds caused the name of the STANVAC CALCUTTA to be perpetuated as a Gallant Ship.

Reference

Gleichauf, F. Justin (2003). Unsung sailors: The Naval Armed Guard in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

* * *

American Liberty Ship SS Stephen Hopkins

SS Stephen Hopkins was a United States Merchant Marine Liberty ship that served in World War II. She was the only US merchant vessel to sink a German surface combatant during the war.

She was built at the Permanente Metals Corporation (Kaiser) shipyards in Richmond, California. Her namesake was Stephen Hopkins, a Founding Father and signer of the Declaration of Independence from Rhode Island. She was operated by Luckenbach Steamship Company under charter with the Maritime Commission and War Shipping Administration.

Action of 27 September 1942

She completed her first cargo run, but never made it home. On September 27, 1942, en route from Cape Town to Surinam, she encountered the heavily armed German commerce raider Stier and her tender Tannenfels. Because of fog, the ships were only 2 miles (3.2 km) apart when they sighted each other.

Ordered to stop, Stephen Hopkins refused to surrender, and Stier opened fire. Although greatly outgunned, the crew of Stephen Hopkins fought back, replacing the Armed Guard crew of the ship's lone 4-inch (102 mm) gun with volunteers as they fell. The fight was fierce and short, and by its end both ships were wrecks.

Stephen Hopkins sank at 10:00. Stier, too heavily damaged to continue her voyage, was scuttled by its crew less than two hours later. Most of the crew of Stephen Hopkins died, including Captain Paul Buck. The 15 survivors drifted on a lifeboat for a month before reaching shore in Brazil.

Captain Buck was posthumously awarded the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal for his actions. So was US Merchant Marine Academy cadet Edwin Joseph O'Hara, who single-handedly fired the last shots from the ship's 4-inch gun. Navy reservist Lt. (j.g.) Kenneth Martin Willett, commander of the Armed Guard detachment which manned the ship's 4-inch gun, was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.

The Liberty ships SS Paul Buck, SS Edwin Joseph O'Hara, and SS Richard Moczkowski, and the destroyer escort USS Kenneth M. Willett were named in honor of crew members of Stephen Hopkins, and SS Stephen Hopkins II in honor of the ship itself.

Recognition

O'Hara Hall, the gymnasium facility at the United States Merchant Marine Academy, is named in honor of Midshipman O'Hara.

Captain Paul Buck, master of SS Stephen Hopkins, was given the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal by The President of the United States. For determination to fight his ship and his perseverance in engaging the enemy to the utmost until his ship was rendered helpless. The award was given by Admiral Emory S. Land.

George S. Cronk, Second Engineer on the ship, sailed his lifeboat 2,200 miles for 31 days to save his shipmates. He was given the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal by the President of the United States. The award was given by Admiral Emory S. Land.

SS Stephen Hopkins was awarded the Gallant Ship Award for outstanding courage against overpowering odds by the U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration.

Name: Stephen Hopkins

Namesake: Stephen Hopkins

Builder: Permanente Metals Corporation

Launched: May 1942

Fate: Sunk in battle September 27, 1942

Class and type: Liberty ship

Tonnage: 7,181 GRT

Length: 441.5 ft (135 m)

Beam: 57 ft (17 m)

Draught: 27.75 ft (8 m)

Propulsion: triple expansion, 2,500 ihp (1,900 kW)

Speed: 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph)

Armament:

1 × 4 in (102 mm)/50 caliber gun (Mark 9)

2 × 37 mm cannon

6 machine guns

|

| S.S. Stephen Hopkins just after launching on April 11, 1942. |

|

| S.S. Stephen Hopkins fitting out at Kaiser Ship Yard No. 2, Richmond, California, in late April 1942. |

|

| S.S. Stephen Hopkins. |

|

| Cadet O'Hara fires shells at the Stier. Tannenfels is also on fire in the distance. Painting by W.M. Wilson. |

|

| One of the unsung heroes of World War II, Chief Engineer Rudolph A. Rutz of the Merchant Marine gave up his life while helping to save other crewmen aboard the doomed Stephen Hopkins. |

|

| S.S. Stanvac Calcutta. |

|

| S.S. Stanvac Calcutta. |

|

| USN Intelligence Report into sinking of HSK Stier (Raider “J’). |

|

| Model of S.S. Stephen Hopkins. |