by Joseph Bryan III

Published in 1949

Although the Battle of Midway was fought on 3-6 June 1942, it had been precipitated six weeks before, on 18 April. At eight o’clock that morning, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey blinked a signal from his flagship, the carrier Enterprise, then 650 miles off Tokyo, to Captain Marc A. Mitscher, of the carrier Hornet, nearby. The signal read: “Launch planes. To Colonel Doolittle and his gallant command, good luck and God bless you.”

As Doolittle had hoped, his raid deceived the Japanese into assuming that he had jumped off from a land base—“Shangri-La,” President Roosevelt announced jocosely. Officers of the Imperial General Staff measured their charts. Excepting the sterile and unlikely Aleutians, the American outpost nearest Tokyo was Midway Island, 2,250 miles eastward. Not only must this be Shangri-La, the Japanese concluded, but it was additionally dangerous as “a sentry for Hawaii,” 1,140 miles farther. They had long contemplated seizure of “AF,” their code name for Midway. The commander in chief of their navy, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto—a stocky, black-browed man with two fingers missing from his right hand—had only to designate the forces and set the date. This he now did. By the end of April the ships chosen for Plan MI—Midway Island—were being mustered from the fringes of the empire.

Right then, a full month before the first gun was fired, Yamamoto lost the battle—for the same reason that, precisely a year after the Doolittle raid, he would lose his life. Certain ingenious men in the United States Navy had broken Japan’s most secret codes, and when Yamamoto flashed Plan MI to his subordinate commanders, these phantoms were eavesdropping at his shoulder.

Their hearing was not quite 20/20. They weren’t entirely sure whether D Day would be at the end of May or early in June—nor whether AF was Midway or Oahu. COMINCH, Admiral Ernest J. King, thought Oahu at first, but CINCPAC, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, thought Midway. He flew out there from Pearl on 2 May, along the curve of those small, sparse wave breaks with the oddly poly-lot names: Nihoa, French Frigate Shoal, Gardner Pinnacles, Lisianski Island, Hermes Reef, and finally Midway. Except that Nimitz was in a Catalina, not a schooner, he might have been Robert Louis Stevenson, making the same landfall fifty years before:

“I eagerly scanned that ring of coral reef and bursting breaker, and the blue lagoon which they enclosed. The two islets within began to show plainly… low, bush-covered, rolling strips of sand, each with glittering beaches, each perhaps a mile or a mile and a half in length… Over these, innumerable as maggots, there hovered, chattered, screamed and clanged, millions of… seabirds.”

The lagoon is about six miles across, and the islets, Sand and Eastern, lie just inside the southern reef. Sand Island is about 850 acres; its highest point is thirty-nine feet. Eastern, less than half the size, also has less freeboard. Both are arid, featureless and uninhabited, yet they are far more important than many larger, lusher islands. The name of the atoll tells why—midway across the Pacific, it is strategically invaluable.

The Navy realized this as early as 1867 and spent $50,000 to have Midway surveyed and an anchorage dredged. But for the next thirty years its only visitors were Japanese, collecting feathers for millinery. In 1903, Midway was made a naval reservation, and in 1904 a cable station was built on Sand; then followed another thirty-year silence, until Pan American Airways arrived to develop a seaplane base. Midway’s name was becoming known now. Soon afterward it rang from Washington to Tokyo. A board of naval officers headed by Rear Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn reported to Congress that “an air base at Midway Island is second in importance only to Pearl Harbor.”

The report was made public in December 1938. Heavy construction started on Midway almost at once. A Marine garrison was sent out in September 1940. The naval air station was commissioned in August, 1941. By 7 December, Midway represented a military investment of $20,000,000.

Sixteen hours after war struck Pearl, it flicked Midway. Night had fallen when two Japanese destroyers crept close inshore and bombarded Sand, killing four men and wounding ten, burning some buildings and destroying some stores. In January a submarine lobbed a dozen shells at the radio station, and twice again in February. In March, Marine fighter planes shot down a flying boat, presumably from Wake, 1,034 miles southwest. Then Nimitz flew in.

Accompanied by Lt. Col. Harold D. Shannon, commanding the 6th Marine Defense Battalion, and Comdr. Cyril T. Simard, commanding the naval air station, he inspected both islands. Each had its own galleys, mess hall, laundry, post exchange, powerhouse and dispensary. The chief difference was that all the aviation facilities, except the seaplane hangars, were on Eastern. For a whole hot day Nimitz strode and climbed and crawled through the establishment, peering at firing lanes, kettles, ammunition dumps, repair shops, barbed wire, underground command posts. He said nothing about his secret information, but he asked Shannon what additional equipment was needed to withstand “a large-scale attack.” When Shannon told him, Nimitz emphasized the point again: “If I get you all these things you say you need, then can you hold Midway against a major amphibious assault?”

“Yes, sir.”

Soon after Nimitz returned to Pearl, he wrote Simard and Shannon a personal letter, addressed to them jointly. He was so pleased with what they had accomplished that he was recommending them for promotion. The Japanese, he continued, were mounting a full-scale offensive against Midway, scheduled for 28 May. Their forces would be divided thus, and their strategy would be so. He was rushing out every man, gun and plane he could spare. He hoped it would be enough.

By now Nimitz knew for certain that Midway was the objective. A smart young officer, Comdr. Joseph J. Rochefort, in Combat Intelligence’s ultra-secret Black Chamber at Pearl, had suggested instructing Midway to send a radio message, uncoded, announcing the breakdown of its distillation plant. Midway complied, and two days later Pearl’s cryptanalysts intercepted a Japanese dispatch informing certain high commands that AF was short of fresh water.

Nimitz’s letter had a violent impact, but Midway was not dislocated. Although its war had been “cold” so far—begging those few dozen shells—the garrison had stayed taut. Every dawn, patrol planes fanned out westward over a million and a half square miles of ocean. The galleys served only two meals a day. The Marines carried their rifles and helmets everywhere, even to the swimming beaches. At night, everyone went underground, except lookouts. So Simard and Shannon had to make no radical adjustments; they had only to assign priorities to their final efforts, and to absorb their reinforcements as smoothly as possible.

On 25 May Nimitz wrote them again: D Day had been postponed until 3 June. The reprieve let them put the last touches on their defenses. Shannon’s garrison now numbered 2,138 Marines. Simard’s fliers and service troops numbered 1,494, of whom one thousand were Navy personnel, 374 were Marines and 120 Army. Midway was a thicket of guns and a briar patch of barbed wire. Surf and shore were sown with mines—anti-boat, anti-tank, anti-personnel. Every position was armed with even Molotov cocktails. Eleven torpedo boats would circle the reefs and patrol the lagoon, to add their anti-aircraft to that of the ground forces and to pick up ditched fliers.

A yacht and four converted tuna boats were assigned to the sandspit islands nearby, also for rescues. Nineteen submarines guarded the approaches from southwest to north, some at one hundred miles, some at one hundred and fifty, the rest at two hundred.

Defensively, Midway was as tough as a hickory nut. Before a landing force could pick its meat, a bombardment would have to crack it open. That is what worried Simard and Shannon. If enough Japanese ships stood offshore, under a fighter umbrella and out of range of Midway’s coast defenses, and began throwing in a mixture of fragmentation and semi-armor-piercing shells, it would take a lot of planes to beat them off. On 3 June, the first day of enemy contact, Midway had 121—thirty of them patrol planes, slow and vulnerable, almost useless in combat; and thirty-seven others, fighters and dive bombers, dangerously obsolete. Worse, some of their crews were Army, some were Navy and some Marine, and inter-service liaison was little more than a wishful phrase.

Midway’s fliers would write one of the most heroic chapters in the history of forlorn hopes. Their glory is the glory of the Light Brigade and of Pickett’s charge. But if Midway’s security had depended on its air arm alone, its ground arm might have had to throw the Molotovs. Nimitz, however, in addition to fortifying the shores of his orphan island, also fortified its seas.

Only a few ships were available, but he sent them all—the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Hornet, with six cruisers and nine destroyers, comprising Task Force 16; and the carrier Yorktown, with two cruisers and five destroyers, comprising Task Force 17. Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commanding Task Force 16, flew his flag on the Enterprise. Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the over-all commander, flew his on the Yorktown.

The two task forces sortied from Pearl Harbor and rendezvoused on 2 June at “Point Luck,” 350 miles northeast of Midway. A signal searchlight on the Yorktown began to blink, and Spruance’s flag secretary made an entry in the war diary: “Task Force Sixteen [is] directed to maintain an approximate position ten miles to the southward of Task Force Seventeen… within visual signaling distance” [so as not to break radio silence]. Next day he added, “Plan is for forces to move northward from Midway during darkness, to avoid probable enemy attack course.” Then, “Received report that Dutch Harbor was attacked this morning.”

Yamamoto had chosen Dutch Harbor for the opening scene of his Plan AL—Aleutians—which was parallel to Plan MI and had the dual purpose of seizing Aleutian territory and weakening Nimitz’s strength by luring part of it north. Word of the attack was still flashing from command to command when another flash outshone it. Spruance’s flag secretary logged it thus: “Midway search reports sighting two cargo vessels bearing 247 [degrees from Midway], distance 470 miles. Fired upon by anti-aircraft.”

The report was made by Ens. Jewell Reid, who had lifted his Catalina from the Midway lagoon at 4:15, forty minutes before sunrise. Chance did not lead him to the enemy in that waste of water. Nimitz had written Simard, “Balsa’s air force [Balsa was the Navy’s code name for Midway] must be employed to inflict prompt and early damage to Jap carrier flight decks.” Rear Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger put it otherwise: “The problem is one of hitting before we are hit.” As Commander Patrol Wings Hawaiian Area, Bellinger’s job was not merely to state the problem but to find the solution. This is it:

“To deny the enemy surprise, our search must insure discovery of his carriers before they launch their first attack. Assuming that he will not use more than 27 knots for his run-in [to the launching point], nor launch from farther out than two hundred miles, Catalinas taking off at dawn and flying seven hundred miles at one hundred knots will guarantee effective coverage. With normal visibility of twenty-five miles, each Catalina can scan an eight-degree sector. It is desirable to scan 180 degrees [the western semi-circle], so twenty-three planes will be needed.”

Nimitz gave them to him. Not all twenty-three were Catalinas. To share the patrol, the Army sent some Flying Fortresses, Lt. Col. Walter C. Sweeney, Jr., commanding, from the 431st Bombardment Squadron; eight arrived on 30 May and more later. Simard assigned them to the southwest sector—the least likely source of attack—because their crews were comparatively unskilled in recognition of ships, and much depended on clear, accurate reports of the enemy’s power. Besides, the heavily armed and armored Fortresses had little to fear from a brush with an overlapping Japanese patrol from Wake.

Meanwhile, one Catalina had met a direr threat than any enemy plane—a weather front, deep and wide, which developed three hundred miles to the northwest and hung there, mocking Bellinger’s calculations. Such a front would let the enemy creep up to its edge unseen and launch a night attack impossible to intercept. Midway’s only comfort was the probability that the weather screening the enemy from observation would also screen the skies from the enemy, preventing accurate navigation and forcing postponement of his attack until dawn allowed him a position-fix.

But even though—if this guess was good—bombs would not fall until 6:00 a.m. or perhaps 6:30, Simard could not risk an earlier attack catching him with sitting ducks. Accordingly, as soon as the search planes were airborne, the remaining Catalinas and Fortresses also took off, to cruise at economical speed until the search had vouch-safed the first four hundred miles, by which time these heavy planes—including such of the Catalinas as were amphibious—would have consumed enough gas to permit their landing on the cramped, five-thousand-foot strip without jettisoning their bombs or burning out their brakes. The smaller planes—fighters, dive bombers and torpedo planes—did not take off, but they were manned and warmed up, ready to go.

The patrol crews’ schedule was brutal. Midway had enough food, water and sleeping space for essential personnel only. Since maintenance crews were luxuries, the patrol crews were topping their fifteen-hour searches with hours more of repairing and refueling. Worse, a few days before, a blundering sailor had tripped the demolition charges under the aviation fuel tanks—“They were foolproof,” a Marine officer said, “but not sailor-proof”—and from then on, all planes had to be refueled by hand from unwieldy fifty-five-gallon drums.

The hard grind was forgotten, however, when Ensign Reid reported, “Two cargo vessels—” and twenty-one minutes later, “Main body bearing 261, distance seven hundred miles. Six large ships in column.” Reid was wrong. This was not Yamamoto’s main body; it was only a small part of one task group in his occupation force. His main body had not been sighted yet, nor had his striking force.

The occupation force, approaching from the southwest, consisted of two battleships, one seaplane carrier, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, twenty-nine destroyers and four assorted ships, escorting sixteen transports. The invasion troops aboard them were 1,500 marines for Sand Island; 1,000 soldiers for Eastern; fifty marines for little Kure, sixty miles west of Midway; two construction battalions and various small special units. Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo commanded, from the battleship Kongo.

The striking force, hidden by the weather front in the northwest, consisted of two battleships, four carriers, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, sixteen destroyers and eight supply ships. Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who had commanded the striking force at Pearl, commanded again, from the same flagship, the carrier Akagi.

The main body, far to the west, consisted of seven battleships, one light carrier, three light cruisers, thirteen destroyers and four supply ships. Yamamoto commanded from the new battleship Yamato. She and her sister ship, the Musashi, were the most formidable in the world—63,700 tons and mounting nine 18.11-inch rifles.

Plan MI was an exact plagiarism of Simard’s and Shannon’s fears. It called for the striking force to crush Midway’s defenses with a three-day air attack, the main body to follow up with a big-gun bombardment, and the occupation force to put its troops ashore on beaches where only maggots moved.

All morning, radio reports crackled through Midway’s earphones, as search pilots spotted the converging elements of the occupation force. Simard wanted to hit them with the Fortresses, but Nimitz had ordered “early damage to Jap carrier flight decks,” and no carriers had been sighted. Then, at eleven o’clock, Ensign Reid sent a correction: there were eleven ships, not six. By now the Fortresses were back and refueled. Simard decided to attack.

Nine Fortresses, Sweeney leading, took off at 12:30, and four hours later sighted a force of “five battleships or heavy cruisers and about forty others.” Sweeney broke his flight into three Vs and stepped them down at 12,000, 10,000 and 8,000 feet. Extra fuel tanks in their bomb-bays left room for only half a bomb load, four 600-pounders apiece, but the bombardiers thought they hit a heavy cruiser and a transport. The Fortresses had not yet landed when four Catalinas with volunteer crews took off to make—it is still almost inconceivable—a night torpedo attack. Catalinas are not built to lug torpedoes, and their crews are not trained to drop them. Still, three pilots managed to find the enemy force—the one the Fortresses had annoyed that afternoon. They approached from down-moon, to silhouette the ships, and Lt. William L. Richards’ torpedo blew a hole in the tanker Akebono Maru. The attack would have been no more bizarre if the tanker had torpedoed the Catalina.

The weary crews turned their planes back toward the dawn. They were almost home when Midway radioed them that it was under air attack.

Reveille had sounded at three o’clock as usual, and at 4:15 as usual the dawn search took off—eleven Catalinas, scouting for Nagumo’s carriers. As soon as they were clear, the Fortresses—there were now fifteen—flew out to re-establish contact with the occupation force. The planes left behind were motley. Four were Army—Marauders, normally a medium bomber, but here jury-rigged to carry torpedoes. Six more were Navy—Avengers, torpedo planes of a brand-new type. The rest were Marine, belonging to the two squadrons of Marine Air Group 22, Lt. Col. Ira L. Kimes commanding. The fighter squadron, VMF-221, had some stubby little Buffaloes, so slow and vulnerable that they were known as “Flying Coffins,” and a few Wildcats, new and tough and fairly fast. The scout bombing squadron, VMSB-241, also was mongrel, with new Dauntlesses and old Vindicators—so old that the Marines called them “Vibrators” and “Wind Indicators.”

All had been manned since 3:15. Their crews watched the sunrise, grumbling that battle would be better than this everlasting waiting around. Even then battle was approaching, at two hundred miles an hour. For more than half the men it would be the last battle—and the last sunrise—they would ever see.

The Japanese striking force had run from under its sheltering weather front shortly after midnight. Dawn gave Nagumo his position, two hundred miles northwest of his target and just astride the International Date Line. At 4:30 be turned his four carriers into the southeasterly breeze and began to launch “Organization No. 5”—thirty-six fighters (Zeros) and seventy-two bombers (Vals).

Midway received its first warning at 5:25, when a Catalina reported “in clear,” uncoded, “Unidentified planes sighted on bearing 320, distance 100 miles.” The same Catalina reported again at 5:34: “Enemy aircraft carriers sighted 150 miles, 330 degrees.” At 5:52, another Catalina corrected and elaborated this sighting: “Two carriers and battleships bearing 320, distance 180, course 135 [toward Midway], speed 25.” The fourth report was from the Marine radar station on Sand: “Many planes, 89 miles, 320 degrees.”

Midway sounded the alarm, and even as its planes were taking the air, Simard radioed his flight leaders: Fighters to intercept, dive bombers and torpedo planes to hit the carriers, Fortresses to forget the occupation force and head north—“your primary target is the carriers!” By a few minutes past six every plane was airborne that could leave the ground, except one non-combat utility plane. Visibility was excellent, the sea calm.

Fighting 221’s twenty-five operational planes were organized into five irregular divisions. The squadron’s skipper, Major Floyd B. Parks, led a group of three divisions, consisting of eight Buffalos and four Wildcats. The executive officer, Captain Kirk Armistead, led the other two, of twelve Buffalos and one Wildcat. Parks’ group made the first contact. They had climbed to 14,000 feet and had left Midway thirty miles astern when one of his pilots called, “Tally-ho! Hawks at angels 12 [bombers at 12,000 feet], supported by fighters!” Parks pushed over. The time was 6:16.

The Vals were flying in two Vs, one far behind the other with the Zeros below both. Parks’ group, then Armistead’s, fell on the Vals like sheep-killing dogs, but the Zeros fell on the Marines like wolves, slashing and springing back for another slash. Outnumbered as the Marines were and—they immediately realized—hopelessly outclassed, their only chance of escape was to dive at full throttle for the cover of ground fire. Few reached it. Zeros set ablaze one plane after another, then whirled and machine-gunned two of the pilots in their chutes.

The Vals closed their ragged ranks and pressed on. Midway was waiting. All guns were manned, and radar had tracked the flight steadily since 5:55, when it had been picked up. At 6:22, D Battery reported, “On target, 50,000 yards, 320.” And at 6:30, Colonel Shannon ordered, “Open fire when targets are within range.” One minute later, every anti-aircraft battery was firing. The first wave had arrived exactly on the schedule that Shannon and Simard had hypothesized.

These were horizontal bombers, at 10,000 feet. Of the original thirty-six, ground observers now counted only twenty-two. The opening bursts of anti-aircraft were short, but the next scored direct hits on the leading plane and one other. The rest dropped their 533-pound bombs on Eastern and the northeast shore of Sand and were gone before the two broken planes had crashed to earth. Simard and his operations officer, Commander Logan C. Ramsey, were watching the plunge, from the entrance to their underground command post on Sand. When the Vals struck nearby, Simard shouted to the gunners, “Damn good shooting, boys!”

A Negro steward’s mate ran to the wreck of the leader’s plane and heaved his body from the cockpit. Ramsey was searching the pockets when the guns opened up again. He and Simard ducked below.

The second wave was dive bombers, the eighteen—half of them—that Fighting 221 had left. The flight leader dropped his huge 1,770-pounder, followed it down, rolled onto his back, and flew across Eastern at fifty feet, thumbing his nose. The anti-aircraft crews were too astonished to draw beads, until a storm of bombs woke them to his purpose—to distract their attention. Even so, they shot him down almost regretfully. The other Vals pulled out over the lagoon, into the torpedo boats’ fire. When they crashed, they threw up white plumes instead of black. Zeros circled and strafed both islands, then followed the bombers home. Midway’s only air attack of the war had lasted seventeen minutes.

The anti-aircraft gunners had shot down ten Japanese planes and they swore that if their visibility hadn’t been cut by smoke from a burning oil tank, they’d have shot down ten more.

Lieutenant Tomonaga, commanding the strike, radioed Nagumo at 7:00: “There is need for a second attack,” but at 7:07 another report assured him, “Sand Island bombed and great results obtained.”

Simard and Shannon had assayed them by then. Casualties were few—ten dead, eighteen wounded; and ground defense equipment had suffered only slightly—one height finder had been damaged; but many of the less important installations were either flat or sieved or in flames. On Sand, in addition to the oil tank, which burned for two days, the seaplane hangars were afire. The dispensary was a shambles—a section of its roof had been hurled high into the air and the sight of its red cross spinning would not be forgotten.

The laundry was also gone. When Commander Ramsey reported back to Pearl on 12 June, still in his uniform of that morning, Nimitz told him, “I understand you’re crawling with—er—‘eagles,’ so maybe you’d like these silver ones,” and showed him a dispatch recommending his promotion to captain.

Eastern lost its powerhouse, mess hall, galley and post exchange, but the airstrips, a dump of gasoline drums and all radio and radar facilities were untouched—the Japanese presumably intended using them. One freakish bomb had opened the door of the brig. Another—a direct hit on the post exchange—had scattered cigarettes and beer cans like shrapnel. One can plugged a machine gunner in the solar plexus. When his wind came back, he gasped, “I never could take beer on an empty stomach!”

As soon as “all clear” sounded, Colonel Kimes broadcast the order: “Fighters land, refuel by divisions, fifth division first.” No one landed. He broadcast again. Still no one landed. He changed the order to “All fighters land and re-service.” Ten of the original twenty-five touched down, several blowing their tires on the jagged bomb fragments that littered the runway. Of the pilots, six were wounded. Of the planes, only two were fit for further combat.

Fighting 221 would not fight the Zeros again for nine months. How much it had inflicted was uncertain. Since there was no way to reckon the missing pilots’ scores, Intelligence accepted only the claims of the ten survivors.

Fighting 221 had taken fearful punishment, but how—its ordeal was suspended until Guadalcanal; but the other squadrons’ ordeals were just beginning—the ordeals by fire that too often ended in ordeals by water.

When Simard radioed his flight leaders the bearing and distance of the enemy fleet, his intention was a simultaneous strike by all squadrons—by such a swarm of planes attacking from so many directions and elevations that, although they would neither be coordinated nor have fighter cover, the enemy could not protect all his carriers against them. The plan was excellent in theory, disastrous in practice. The attacks were made separately, not simultaneously. As a result, the enemy could focus his deadly attention on one group at a time.

First to fly the gantlet were the six Navy Avengers. The rest of their squadron, Torpedo 8, was aboard the Hornet. These six crews had been detached for a special mission—to battle-test the new Avenger against the fleet’s only other torpedo plane, the obsolescent Devastator. Their flight leader was Lieutenant Langdon K. Feiberling, USN. Four of the other pilots were reserve ensigns, and the fifth was an enlisted man. Their crews included two more ensigns, Catalina pilots, who had volunteered as navigators, doubling at the tunnel guns, and a Catalina gunner, who had begged to man the turret for the enlisted pilot, a friend of his.

Before Midway faded astern, they saw the smoke of the first bombs. Then the enemy screen loomed ahead, with two big carriers in the distance. Zeros jumped them at once. Nagumo wrote in his log at 7:10, “Enemy torpedo planes divide into two groups,” and at 7:12 “Akagi [his flagship] notes that enemy planes loosed torpedoes [and] makes full turn to evade, successfully. Three planes brought down by anti-aircraft fire.” Zeros continued to hammer the remaining three. Two wavered, then splashed in. The last, riddled and broken, and its pilot, Ensign Albert K. Earnest, bleeding from a shrapnel wound, somehow lurched on.

Earnest could not defend himself. His own guns were jammed; his turret was shattered, the gunner killed; and his tunnel gun, served by a wounded radioman, was blanked by the dangling tail wheel. Nor could he even dodge. His elevator control was cut and his hydraulic system smashed; the bomb-bay doors hung open, damping speed, and one landing wheel hung down, dragging the plane askew. The Zeros chased him for fifteen miles and turned back then only because their ammunition belts were empty. Earnest wiped the blood from his eyes, guessed his homeward course—his compass was splintered—and staggered in. The Avenger crashed when it landed, but Earnest crawled out alive, to make his report.

Nagumo’s respite was brief. He had hardly shaken off the Avengers when he was under torpedo attack again, by the four Marauders of the Army’s 69th Medium Bombardment Squadron, Captain James F. Collins, Jr., commanding. They had been the last to leave Midway, beating the bombs by mere minutes, but their speed had overtaken the Dauntlesses and Vindicators, now trudging astern. Even as Collins sighted the enemy force, a line of Zeros swung toward him. He led his flight straight at them, then ducked toward the water. One pilot yelled, “Boy, if mother could see me now!” A black wall of anti-aircraft solidified ahead. Two Marauders crashed into it and fell, but Collins and Lieutenant James P. Muri broke through. Again the Akagi was the target. Collins dropped his torpedo at eight hundred yards; Muri closed to 450 and barely cleared her flight deck on his pull-up. Each thought he had scored, but Nagumo recorded at 7:15, “No hit sustained.”

Zeros chased them out to the screen, wrecking Muri’s turret and killing his tail gunner. Collins’ turret could fire only in jerks, and his tail gun was jammed. Yet their two crews shot down three Zeros, maybe four, and the crippled Marauders—one’s landing gear had been shot away, and the other, burning, had more than five hundred holes—held together just long enough. When they touched down at Eastern, they were junk.

Meanwhile, Sweeney’s fifteen Fortresses, heading westward since before dawn in search of the occupation force, had turned north as soon as they picked up Simard’s six o’clock relay of the position report on the striking force. They sighted it at 7:32, but Sweeney held his bombs. His primary target was the two carriers, and both were hidden by clouds. He began to orbit at 20,000 feet, hoping that they would venture out.

Actually, four of them were down there, all veterans of the attack on Pearl: the Kaga (“Increased Joy”) and Akagi (“Red Castle”), slightly smaller than our big Essexes; and the sisters Soryu (“Blue Dragon”) and Hiryu (“Flying Dragon”), slightly smaller than our light Independence class. The Akagi and Hiryu were unique among the type; their superstructures—“islands”—rose from their port sides.

In twenty minutes Sweeney had his hope. The Soryu reported, “Fourteen [sic] enemy twin-engine [sic] planes over us at 30,000 meters [sic].”

Nagumo logged at 7:55: “Enemy bombs Soryu (nine or ten bombs). No hits.” And a minute later: “Noted that the Akagi and Hiryu were being subjected to bombings.”

The carriers fired a few bursts of anti-aircraft, then ran back under the clouds, leaving further defense to their CAP—combat air patrol. The Zeros had no stomach for the stalwart Fortresses; their passes were cautiously wide.

Sweeney was surprised: “Hell, I thought this was their varsity!”

As he resumed his watchful orbit, the Marines poured in—Scout Bombing 241’s first attack group, sixteen Dauntlesses, Major Lofton R. Henderson commanding. Ten of the pilots had not joined the squadron until the week before, and thirteen were totally inexperienced in Dauntlesses, so Henderson decided not to dive-bomb, but to glide-bomb, a shallower, easier maneuver. He was spiraling down from nine thousand feet to his attack point at four thousand when the Japanese fighters caught them. The Marine rear seat men splashed four, but the Japanese pilots and their ships’ anti-aircraft splashed six Dauntlesses, two in flames. One was Henderson’s. Seeing him burn, Captain Elmer C. Glidden, Jr., second in command, moved into the lead. Below him was a cloud bank. He dived for it to lose his pursuit and broke through dead above the Akagi. Three fighters had just left her deck. She had gone to battle speed when she first spotted the Dauntlesses, and now she was writhing in her course.

Glidden pushed over and dropped his bomb from five hundred feet, with the nine other pilots strung out astern. All managed to get clear of the Japanese force, but on their way home, damage dragged two more planes into the sea, and of those that landed, another two would never fly again. The pilot of one, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson, Jr., mentioned that his throat microphone had been shot away, and added that his plane had been hit “several times.” His rear seat man later counted 259 holes.

Henderson’s group reported that their 500-pounders scored two hits and a near miss, and Captain Aoki of the Akagi has testified that this is the exact tally of her injuries, which proved fatal. However, there is also evidence that she suffered them in a subsequent attack.

Parks, Feiberling, Henderson: three American flight leaders had been killed, and the battle was not yet two hours old.

Meanwhile, the carriers’ evasive tactics were intermittently taking them under open sky. So the Fortresses, still at 20,000 feet, began to pot-shoot, then turned homeward, their bombs exhausted.

That was at 8:24. Three minutes later, Nagumo wrote: “Enemy planes dive on the [battleship] Haruna.” The Marines were striking again. These were VMSB-241’s second attack group, eleven lumbering Vindicators, led by Major Benjamin W. Norris. The pilots were as green as Henderson’s—nine of them had never flown a “Vibrator” before 28 May. They approached the enemy force at 13,000 feet and had just sighted it, twenty miles off, when three Zeros, doing graceful vertical rolls, ripped through their formation. One amazed Marine said, “Those Japs put on a good show—very good for us, since more attention to business might easily have wiped out eleven of the slowest and most obsolete planes ever to be used in the war.”

The concentrated .30-caliber fire of four rear seat men knocked one Zero down. More Zeros joined in, and another went down. Norris headed for the clouds at top speed. When he burst out, at two thousand feet, he expected to find the carriers below. Instead, he was short, and directly above the Haruna, zig-zagging in the van of the formation near her sister, the Kirishima.

Norris now faced a split-second decision. The carriers were his target, but his low altitude would make it suicidal to attempt taking these vulnerable planes—their skin was partly fabric—through the intense anti-aircraft of the whole force. On the other hand, the Haruna not only was close below but might not be alert against attack, as the carriers certainly were. He chose the Haruna. The air was so rough with shell blasts that the Marines could hardly hold their planes in a true dive. Geysers rose near the Haruna, and one splashed on the Kirishima’s fantail, but Nagumo wrote: “No hits.”

The Zeros were waiting at the screen. They shot down two Vindicators and shot away another’s instruments and elevator control; the pilot limped as far as possible, then ditched in the sea near Kure. The scattered rest made it back as best they could. Even in his harried dive, Norris had radioed them: “Your course is one-four-zero,” but there were only four plotting boards among the group, and most of the pilots navigated by thumb until they could home on the black pillar from the burning oil. The last of them touched down at ten o’clock.

They had left Midway neat and taut. Now it was debris. The spring morning stank of ruin. Buildings were a jackstraw pile of charred timbers. The upheaved sand, littered with thousands of dead birds, was still cold under foot. Silence lay on the once-buzzing airstrips. Two thirds of the combat planes were smashed or lost; half the aircrewmen were killed or missing. And the enemy’s four deadly carriers were still intact.

Ashore, the situation seemed grave. But afloat, our own carriers had joined the battle.

Dawn on 4 June found the American forces about 220 miles northeast of Midway. A four-knot breeze blew from the southeast. Clouds were low and broken, with visibility twelve miles. Admiral Fletcher’s Task Force 17, built around the Yorktown, was steaming ten miles to the north of Admiral Spruance’s Task Force 16, built around the Hornet and Enterprise. Fletcher, the Senior Officer Present Afloat and Officer in Tactical Command, knew that the enemy’s occupation force had been sighted west of Midway, but he did not close its position. His target was the striking force, which was expected to approach from the northwest. The Yorktown’s scouts had searched that sector on the third; half an hour before sunrise next morning, Fletcher sent them out again. An hour later, at 5:34, he intercepted the first of the reports that the Catalinas were flashing back to Midway, but not until 6:03 did they give him what he wanted: “Two carriers and battleships,” with their bearing, distance, course and speed.

His staff laid out the data on a plotting board. The carriers were too far to be reached with an immediate strike. However, if the Japanese commander held his course—and likely he would, to take advantage of the head wind in landing his first attack wave and launching a second—an intercepting course would soon bring him within range. At 6:07 Fletcher ordered Spruance: “Proceed southwesterly and attack enemy carriers when definitely located. I will follow as soon as my planes are recovered.”

Spruance headed out at twenty-five knots. The range had closed sufficiently by seven o’clock. His task force swung into the wind, and the first plane roared down the Enterprise’s flight deck. Her Air Group 6 launched fifty-seven in all: ten fighters (Wildcats), thirty-three dive bombers (Dauntlesses), and fourteen torpedo planes (Devastators). Nearby the Hornet’s Air Group 8 was launching almost identically: ten Wildcats, thirty-five Dauntlesses and fifteen Devastators. Each group was ordered to attack one of the carriers, now an estimated 155 miles southwest. The launch was completed by 8:06. The task force swung out of the wind and the six squadrons sped away.

But if Fletcher blessed the scout who found Nagumo, Nagumo had one of his own to bless. At 7:28, halfway through Spruance’s launch, Nagumo’s scout sent back this message: “Sight what appears to be ten enemy surface ships in position bearing 10 degrees, 240 miles from Midway. Course 150, speed over 20 knots.”

Nagumo at once ordered his force, “Prepare to carry out attacks on enemy fleet units!”; then told the scout, “Ascertain ship types and maintain contact.”

“Enemy is composed of five cruisers and five destroyers,” the scout replied. Presently he added, “Enemy is accompanied by what appears to be a carrier.”

By now the Enterprise had picked him up on her radar and had sent her combat air patrol to make the kill. He was still there, still transmitting—“Sight two additional enemy cruisers in position bearing 8 degrees, distance 250 miles from Midway. Course 150 degrees, speed 20 knots”—but the CAP (combat air patrol) pilots could not find him. It made little difference; the damage was already done. A few minutes later he signed off: “I am now homeward bound.” The time was 8:34; he had been in the air since five o’clock, and the needles of his fuel gauges were drifting toward “empty.”

Major Norris’ old Vindicators were swarming over the Haruna and Kirishima just then, and Nagumo had no leisure until 8:55, when he curtly ordered the scout: “Postpone your homing. Maintain contact with the enemy until arrival of four relief planes. Go on the air with your long-wave transmitter” [to give them a radio bearing].

Nagumo then told his captains, “After completing homing operations [recovering the planes that had struck Midway], proceed northward. We plan to contact and destroy the enemy task force.” They had built up speed to thirty knots when, at 9:18, a lookout sighted fifteen American planes, close to the water. They were the Hornet’s Torpedo 8, Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron commanding—the rest of the squadron whose six Avengers had already flown from Midway to enduring glory.

It will never be known how, of the six squadrons launched, Waldron’s plodding, 120-knot Devastators were the first by half an hour to find the enemy. It is known only that they did not rendezvous with the rest of the Hornet’s strike, as they should have; said a fighter pilot who saw them, “They just lit a shuck for the horizon, all alone.”

Although the Japanese carrier force was now far from its predicted position—it had maneuvered radically to dodge Midway’s planes, then had turned northeast to attack Spruance—Waldron flew a confident course, straight into its guns. He had lost his own fighters, and Zeros were ahead, astern and around him. The anti-aircraft was almost thick enough to screen the twisting ships; it gored huge holes in wings and fuselages, cut cables, smashed instruments, killed pilots and gunners. Plane after torn plane—fourteen of them—plunged into the sea, burned briefly and sank. A rear seat man in another squadron, miles away, overheard Waldron’s last words: “Watch those fighters! … How’m I doing? … Splash! … I’d give a million to know who did that! … My two wingmen are going in the water…”

The rest of Torpedo 8 is silence, except for the voice of its sole survivor, Ensign George H. Gay. He heard Waldron and he heard his own gunner cry, “They got me!” Then he was hit himself, twice, in the left hand and arm. He squeezed the bullet from his arm and popped it into his mouth. His target was the Kaga. He dropped his torpedo and flew down her flank, close to the bridge—“I could see the little Jap captain jumping up and down and raising hell.”

A 20-mm shell exploded on his left rudder pedal, ripping his foot and cutting his controls, and his plane crashed between the Kaga and the Akagi. He swam back to get his gunner, but strafing Zeros made him dive and dive again; the gunner sank with the plane. A black cushion and a rubber raft floated to the surface. Gay was afraid to inflate the raft; it might draw the Zeros. He put the cushion over his head and hid under it until twilight, peeking out to watch the battle. Tossed by the wash of Japanese warships, wounded, alone, the only man alive of thirty who had been vigorous a few moments before, Gay remembered their training at Norfolk, and how a farmer had complained that their practice runs were souring his cows’ milk.

When Winston Churchill was told about Torpedo 8, he wept.

Gay was shot down at about 9:40. At 9:58, Nagumo wrote: “Fourteen enemy planes are heading for us.” They were the Enterprise’s Torpedo 6, Lieutenant Commander Eugene E. Lindsey commanding. Not only had they, too, lost their fighter cover, but they were attacking an enemy alerted by the previous attack. Before a torpedo pilot can drop with any hope of a hit, he must maintain a steady course and altitude for at least two minutes. A full squadron of Zeros pounced on Torpedo 6 at this vulnerable time. Ten of the Devastators, including Lindsey’s, were shot down at once, most with their torpedoes still in the slings. The other four escaped only because the Zeros were called away to meet a new threat, the Yorktown’s Torpedo 3.

The principal contact report had mentioned only two enemy carriers, but Intelligence had warned Fletcher that two more would be present. Rather than risk their planes’ catching the Yorktown with hers on deck, he decided to send about half of them to reinforce the Hornet’s and Enterprise’s and to hold the rest until the two missing carriers were reported.

The Yorktown group—twelve Devastators, seventeen Dauntlesses and six Wildcats—was in the air by 9:30. This once the torpedo planes had the cover they needed so desperately; their fighters clung to them the whole way. Better yet, the Enterprise’s fighters, which had become separated from their own torpedo squadron, joined up in support. They sighted the enemy at ten o’clock, but they still had fourteen miles to go when Zeros caught them. The sixteen Wildcats were outnumbered two to one. The fast Zeros splashed three, then sped after the Devastators. By now their commander, Lieutenant Commander Lance E. Massey, had worked his way within a mile of the Akagi. As he turned to make his run, a Zero shot him down in flames. Six more of his squadron fell. The remaining five made their drops, then the Zeros shot down another three. The last two escaped.

Of the forty-one torpedo planes which the American carriers had sent into battle, thirty-five had now been lost. Of the eighty-two men who flew them, sixty-nine had been killed, including the three squadron commanders. And of the torpedoes they dropped, not one had scored a hit. Yet these men did not die in vain. The valor that drew the world’s admiration also drew the enemy’s attention. His dodging carriers could not launch a new strike. And while every gun in his force trained on the torpedo planes, and every Zero in the sky fell on them, our dive bombers—unopposed, almost unnoticed—struck the Kaga, the Akagi and the Soryu their death blows.

The thirty-three Dauntlesses of Scout Bombing 6, led by Lieutenant Commander Clarence Wade McClusky, Jr., commanding the Enterprise’s air group, had climbed up the estimated bearing of the enemy force until they should have been on top of it. McClusky cocked his wing and looked down. Visibility was perfect, except for a few small clouds. From his altitude of 20,000 feet, he could see more than 95,000 square miles of ocean. A hundred miles southeast of him was a tiny blur—Midway. But Midway was all he saw; the rest of the ocean was empty. He held on for another seventy-five miles. Still nothing, and time was running out. Merely finding the enemy carriers would not be enough. McClusky had to find them before they could launch a strike against our own carriers. Where were they? He had to guess fast and guess right.

When the Hornet’s group reached the estimated position and faced the same guess, their leader sent twenty-two of his bombers home and pressed forward with the rest—thirteen Dauntlesses and ten Wildcats. Like McClusky, he held southwest for half an hour, but then—with emptiness still ahead—he turned southeast, toward Midway, and then northeast. His determination to attack ignored the insistencies of his fuel tanks, and when he finally abandoned the search, it was too late for most of his planes to make even Midway. The Wildcats gasped and ditched, one after another, all out of fuel; only eight of the pilots were rescued. Two of the Dauntlesses died over the Midway lagoon; their crews waded mere yards to the beach. The other eleven landed with their last pints, at 11:20. Their welcome was something less than effusive. Not expecting the Dauntlesses, and seeing them jettison their bombs offshore, the Marine lookouts mistook them for enemy planes, blew the air raid siren and even scrambled one of Fighting 221’s riddled fighters to intercept them.

But McClusky decided that the enemy had reversed his southeast course—Captain George D. Murray, of the Enterprise, called it “the most important decision of the entire action”—so he headed his bombers northwest. They had already burned up nearly half their fuel; if he didn’t find his target soon, our task forces would lose his planes as well as their ships. Fifteen minutes passed, twenty, twenty-five, before his eye caught a faint white streak below—the wake of a lone Japanese destroyer; and presently, far to the north, three carriers, veering and twisting among their escorts, slid out from the broken overcast—the Soryu in the lead, with the Kaga to the west and the Akagi to the east. The Hiryu, bringing up the rear, stayed under the clouds and was never seen.

McClusky split his attack: half for the Kaga, half for the Soryu. He took a last look around—still no Zeros—and pushed over. The enormous red “meat balls” on the yellow flight decks became as sharply defined as bull’s-eyes.

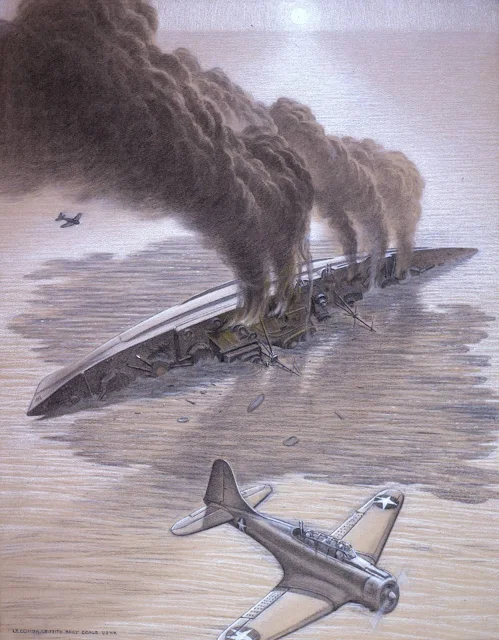

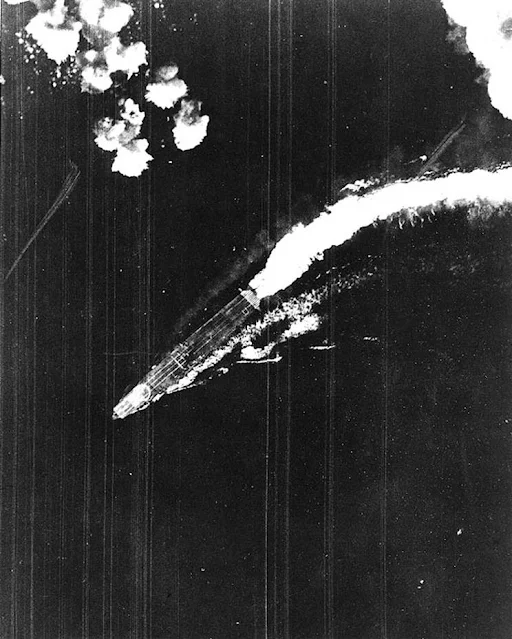

Nagumo’s strike against the American carriers was just about to take off. The Kaga had thirty planes on her flight deck and thirty more on her hangar deck, all armed and fueled. They were awaiting the signal when four bombs struck her, shattering her bridge and killing every man on it, including Captain Okada. Explosions leaped from plane to plane, from deck to deck. A solid pillar of fire shot 1600 feet into the air. Smoke shrouded her, a black pall slashed with scarlet, and the blinded helmsman let her run wild.

The Soryu also had sixty planes aboard. Three bombs spattered blazing gasoline fore and aft on her hangar deck. A magazine exploded; both engines stopped; she lost steerageway. Captain Yanagimoto shouted from the bridge, “Abandon ship! Every man to safety! Let no man approach me! Banzai! Banzai!” He was still shouting banzais when flames rose around him. Most of the company struggled to the forward end of the flight deck, out of the fire and smoke, and huddled there until a violent explosion blew them into the sea.

The Enterprise’s Bombing 6 struck the Kaga and the Soryu at 10:23. At the same minute, unknown to them, the Yorktown’s Bombing 3 was plunging on the Akagi, Nagumo’s flagship. Some of her Midway group had not yet returned, so she had only forty planes aboard. Her fighters tried to get clear. As the first of them gathered speed, the first bomb smashed among them, near the midships elevator, and another hit the portside aft. Damage did not seem severe, but when Captain Aoki ordered the magazines flooded, the after pumps would not function. The bridge took fire from a burning fighter below and the fire spread. Nagumo summoned a destroyer to transfer himself and his staff to the light cruiser Nagara. Within an hour, the Akagi’s flight deck flamed from end to end. Suddenly her engines stopped. An officer investigated. Her whole engine room staff was dead.

The torpedo attacks had drawn the Zeros to water level, so they needed only a short sprint to catch Bombing 6 after the pull-out. Eighteen of McClusky’s thirty-three Dauntlesses splashed in—he himself was wounded in the shoulder—but fuel exhaustion was to blame for some of them. Bombing 3 returned intact to the Yorktown’s landing circle, only to have her warn them away. Before the Enterprise could take them aboard, two of the seventeen ran dry and ditched. Worse, a Yorktown fighter pilot, shot in the foot, crash-landed on the Hornet without cutting his gun switches. His six .50’s jarred off, and the burst killed five men and wounded twenty.

The Yorktown warned away her planes because her radar had picked up an incoming strike. Two hours before, at ten o’clock, Nagumo had reported Task Force 17’s position to Yamamoto: “After destroying this, we plan to resume our AF attack.” At 10:50 he admitted, “Fires are raging aboard the Kaga, Soryu and Akagi,” but added firmly, “We plan to have the Hiryu engage the enemy carriers.” And at 10:54 the Hiryu’s blinker boasted: “All my planes are taking off now for the purpose of destroying the enemy carriers.”

“All” was an exaggeration; the strike consisted of only nine fighters and eighteen bombers. As soon as they appeared on the Yorktown’s radar screen, at 11:50, her combat air patrol dashed to intercept them. Ten bombers went down at once and anti-aircraft knocked down five more, but three bombs struck the ship, and one of them hurt her. It tore through to her third deck and exploded in the uptakes, blasting out the fires in two boilers and flooding the boiler rooms with fumes. It also set the paint on her stack ablaze and ruptured the main radio and radar cables. Steam pressure fell; she lost way and went dead in the water.

Fletcher took a quick turn around the flight and hangar decks. When he climbed back to flag bridge, he found it wreathed in smoke so dense that his blinkers and flag hoists were blanketed. With all communications gone, he and the key men of his staff slid down a line and transferred to the heavy cruiser Astoria. Meanwhile, the Yorktown’s repair gangs patched her decks, and the engineering force coaxed her up to twenty knots. By two o’clock she was shipshape again—she even hoisted a bright new ensign to replace one stained by battle smoke. It had scarcely shaken out its folds when another ship’s radar picked up a second attack group, thirty miles to the west—six fighters and ten torpedo planes, from the Hiryu as before. Fletcher’s task force was now alone, Spruance was thirty miles eastward, farther from the enemy, since launching and landing had kept the Hornet and Enterprise on an easterly course. However, Spruance had sent Fletcher two heavy cruisers, and two destroyers as anti-aircraft reinforcements. The Yorktown’s CAP and the combined anti-aircraft splashed six of the torpedo planes, but four broke through and made their drops at her. The heavy cruiser Portland tried in vain to interpose herself. Two torpedoes struck the Yorktown’s port flank, almost in the same midships spot. A witness said, “She seemed to leap out of the water, then sank back, all life gone.” The time was 2:45.

Dead, dark, gushing steam, she drifted in a slowing circle to port. Her list increased to twenty-six degrees; her port scuppers were awash, and she seemed about to capsize. Stretcher bearers threaded her steep passageways, collecting the wounded. At 2:55, Captain Elliott Buckmaster ordered, “Abandon ship!” Destroyers stood in. Swimmers climbed aboard and clotted their decks in a whispering deathwatch, but the Yorktown floated on. The late afternoon was beautiful, with a calm sea and a flamboyant sunset. A CAP pilot above Spruance’s force, still steaming eastward, looked back at the stricken ship, deserted except by a destroyer. He thought of her as a dying queen, and his eyes were hot with sudden tears.

So far, no American had seen more than three Japanese carriers at one time, and three were known to have been crippled at 10:23. However, this torpedo plane attack, nearly four and a half hours later, strongly supported the prediction of a fourth carrier. Fletcher had not long to wait for positive corroboration. Even as the Yorktown still reeled, one of her scouts reported, “one CV [carrier], two BB [battleships], three CA [heavy cruisers], four DD [destroyers], lat 31-15 N, long 179-05 W [about 160 miles west of Spruance’s task force], course 000 [due north], speed 15.”

Fletcher ordered the Enterprise and Hornet to strike immediately. The Enterprise completed her launch first. By 3:41, she had twenty-four Dauntlesses in the air, including fourteen refugees from the Yorktown. They had flown about an hour when they saw three large columns of smoke from the burning Kaga, Akagi and Soryu. A few destroyers were standing by them; the rest of the force was some miles to the north, fleeing with the surviving carrier, the Hiryu. The bombers swung westward in order to dive out of the blinding afternoon sun, and pushed over from 19,000 feet. They lost three planes to Zeros, but they laid four heavy bombs on the Hiryu’s deck and three more just astern, starting such enormous fires that the last pilots in line saw that she was already doomed and kicked over to bomb a battleship near by. When the second half of the strike—sixteen more Dauntlesses, from the Hornet—arrived a half hour later, they ignored the Hiryu completely and dropped on a battleship and cruiser. All the Hornet’s planes returned.

The Hiryu’s forward elevator was blasted out of its well and hurled against the bridge, screening it and preventing navigation. She had only twenty planes aboard, but they were enough to feed the fires, which quickly spread to the engine room. Her list reached fifteen degrees. She began to ship water.

Of the four carriers, the Soryu was the first to sink. A picket submarine, the USS Nautilus, spied her smoke, crept within range, and shot three torpedoes into her at 1:59. Her fires blazed up, but died by twilight, and boarding parties were attempting to salvage her when she plunged, at 7:13. Fifty miles away, Ensign Gay, under his black cushion, had been watching the burning Kaga. Several hundred of her crew were still huddled on her flight deck when a heavy cruiser—Japanese—began firing point-blank into her water line. Two explosions tore her apart. She sank twelve minutes after the Soryu.

The Akagi and the Hiryu also sank within minutes of each other, but not until next morning, 5 June. The Akagi was stout. Her dead engines, staffed by dead men, suddenly came to life and turned her in a circle for nearly two hours, until they stopped forever. Still she would not sink. One of her destroyers torpedoed her charred hulk at dawn.

The Hiryu was the flagship of Commander Carrier Division 2, Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, an officer so brilliant that he was expected to succeed Yamamoto as commander in chief. Burly, with a face like a copper disk, he was an alumnus of the Princeton Graduate College and had been the chief of Japanese Naval Intelligence in the United States. When he and Captain Kaki, of the Hiryu, saw that she could not be saved, they delivered a farewell address to the crew, which was followed “by expressions of reverence and respect to the Emperor, the shouting of banzais, the lowering of the battle flag and command flag. At 0315 [3:15 a.m.], all hands were ordered to abandon ship, His Imperial Highness’ portrait removed, and the transfer of personnel to destroyers put underway…The Division Commander and Captain remained aboard. They waved their caps to their men and with complete composure joined their fate with that of their ship.” The destroyer Makigumo scuttled her with a torpedo at 5:10.

All four carriers were gone. With them went more than two thousand men. Spruance reported that we now had “incontestable mastery of the air.”

To the top commanders at Midway, meanwhile, 4 June had been a day of deep anxiety. The meager reports that reached them during the morning—only one enemy carrier damaged—made the ruins around them prophetic of worse. Incredibly—but for the confusion of battle—Lieutenant Colonel Sweeney, commanding the Fortresses, had not yet been told of the two United States Navy task forces offshore. Believing that Midway was fighting alone and hopelessly, he sent seven of his planes—all that were ready for instant flight—back to Oahu, both to save them from destruction and to help defend the Hawaiian Islands against the invasion which he assumed would follow Midway’s imminent fall. Although Commander Ramsey, the Air Operations Officer, was better informed, even he thought it “quite possible that we would be under heavy bombardment from surface vessels before sunset.”

Midway’s air strength was now reduced to two fighters, eleven dive bombers, eighteen patrol planes and four Fortresses, plus aircraft under repair. Sweeney led the four Fortresses in the first strike of the afternoon, against the scattered carrier force. Two more, patched up, took off an hour later for the same target. At 6:30, as the pilots made their bombing runs, they sighted another six Fortresses a mile below—a squadron which had flown from Molokai, southeast of Oahu, straight into the battle. All three formations reported bomb hits, but Nagumo’s log acknowledges none.

The Marines tried next. Their eleven dive bombers, Major Norris commanding, went out at dusk, but squalls thickened the moonless sky, and they had to abandon their search. Only the blue glare from their exhausts kept them together until Midway’s oil fires guided them home. Ten returned safely; Major Norris did not return. Midway mounted one more strike that evening. Eleven torpedo boats dashed out at 7:30, hoping to cut down a straggling ship, but they, too, found nothing.

As the torpedo boats left, the Molokai Fortresses landed, with alarming news: Zeros had jumped them during their attack. Midway had learned by now that the enemy’s fourth—and presumably last—carrier had been crippled at 4:30, so Zeros aloft two hours later implied that a fifth carrier was present. Actually the Zeros were orphans from the burning Hiryu, but Midway could not know this. Nor did it know that a patrol craft’s report, at nine o’clock, of a landing on Kure, sixty miles west, derived from simple hysteria. On the contrary, each report strengthened the other. The possibility of invasion became a probability.

Midway radioed its picket submarines to tighten the line against the approaching enemy, and launched two Catalinas with torpedoes to support the interception. The Catalinas took off at midnight. At 1:20, an enemy submarine suddenly fired eight rounds into the lagoon, then submerged. Midway’s belief that this was a diversion to cover a landing party seemed confirmed within an hour, when one of its own submarines, the USS Tambor, reported “many unidentified ships” only ninety miles westward.

The garrison already had done its utmost. There was nothing left now but the ceaseless service of the planes—eighty-five 500-pound bombs to be hung by hand, 45,000 gallons of fuel to be pumped by hand—and waiting out the direly pregnant night.

Far northeast of Midway, the American warships were also waiting. Fletcher’s task force, maimed by the loss of the Yorktown, now merely sheltered behind Spruance’s. The Hornet and Enterprise were unimpaired, but Spruance was wary of the fast Japanese battleships and “did not feel justified in risking a night encounter… On the other hand, I did not wish to be too far from Midway next morning. I wished to have a position from which either to follow up retreating enemy forces or to break up a landing attack on Midway. At this time the possibility of the enemy having a fifth CV [carrier] somewhere in the area… still existed.”

Spruance had cruised slowly east, then a few miles north, east again and a few miles south, when the Tambor’s sighting ended his aimlessness. He headed toward Midway at twenty-five knots.

There, as the morning of the fifth dawned, the Catalinas were off at 4:15, followed by the Fortresses, and at 6:30 the first report came in: “Two battleships streaming oil,” with the bearing, distance, course and speed. They were not battleships but heavy cruisers, the Mogami and Mikuma. The Catalina pilot’s mistake in identification was excusable. These sister ships and their other two, the Kumano and Suzuya, were Japan’s notorious “gyp cruisers”—professedly built to the conditions of the London Naval Conference, but really far larger and more powerful. They were longer, indeed, than any battleship at Pearl Harbor.

The four, a vanguard for the occupation force, had been given a screen of destroyers and sent ahead to bombard Midway in preparation for the landing. They were steaming at full speed when a lookout spotted the Tambor even as she spotted them. An emergency turn was ordered, but the Mogami missed the signal. She knifed into the Mikuma’s port quarter, ripping it open and wrenching her own bow askew, so that neither ship could make more than fifteen knots. The collision occurred soon after 2:00 a.m. At 2:55, Yamamoto’s subordinate commanders received an astonishing dispatch: “Occupation of AF is canceled… Retire…”

Thus far, the enemy’s motives and maneuvers at Midway have been reconstructed from official documents; but on this critical point—why Yamamoto decided to break off the battle—the files are silent. He himself is dead, so only conjectures are left. The most obvious, suggested by chronology, is that he was influenced by the collision of the cruisers, but this was, after all, only a minor mishap to his powerful fleet.

Likelier, the true factors were older than the collision, but new to Yamamoto, owing to faulty fleet communications. At 6:30 the evening before, a scout pilot from one of Nagumo’s ships had reported sighting “four enemy carriers, six cruisers and fifteen destroyers… 30 miles east of the burning and listing carrier… This enemy force was westward bound.” The pilot was myopic. The American force had only two operational carriers by then, and was bound eastward. Still, Nagumo had no reason to doubt the sighting, and although his log does not say so, presumably he informed Yamamoto at once. Yamamoto seems not to have received the message, for at 7:15 he was broadcasting:

The enemy task force has retired to the east. Its carrier strength has practically been destroyed.

The Combined Fleet units in that area plan to overtake and destroy this enemy, and, at the same time, occupy AF.

The Mobile Force [Nagumo], Occupation Force… and Advance Force [submarines] will contact and destroy the enemy as soon as possible.

Nagumo has written: “It was evident that the above message was sent as a result of an erroneous estimate of the enemy, for he still had four carriers in operational condition and his shore-based air on Midway was active.” Accordingly, at 9:30 p.m. he repeated the pilot’s sighting, and again at 10:50. One of these messages must have reached Yamamoto. When it did, the shock of learning that the American force, which he believed crippled and quailing, was both on the offensive—which it wasn’t—and stronger by two unsuspected carriers—which it wasn’t—may have jolted him into ordering the retirement.

All this, it should be emphasized, is conjecture. But it is a fact that the Battle of Midway was over, except for skirmishes.

The first of them was touched off by Catalina’s 6:30 report of “two battleships streaming oil.” The Marine dive bombers jumped to the attack. Two Vindicators had been repaired overnight, so there were six now, led by Captain Richard E. Fleming, and six Dauntlesses, led by Captain Marshall A. Tyler. As the Mogami and Mikuma, accompanied by two destroyers and trailing the Kumano and Suzuya, limped westward, their torn tanks left an unmistakable spoor, and the Marines followed it to their quarry. Through a storm of anti-aircraft, the Dauntlesses dived on the Mogami at 8:05 and bracketed her with near misses that riddled her topsides. Then the Vindicators glided down at the Mikuma. Smoke gushed from a hit on Fleming’s engine, but he held his course. The men behind him saw his bomb drop, saw his whole plane burst into flames, and saw him crash it into the Mikuma’s after turret. Captain Akira Soji, of the Mogami, said, “He was very brave.” The Marine Corps agreed; Fleming was the first Marine aviator of the war to receive the Medal of Honor.

This was Midway’s last successful action. The Fortresses made three more strikes that day, against the two cruisers and other units, but none was effective and one was tragic. Two planes, out of fuel, had to ditch, with the loss of ten men—the Fortresses’ only casualties in the air battle.

The 6:30 report of “two battleships” reached Spruance too, but the weather was foul in his area, so he kept his planes on deck, hoping for better flying and a fatter target. Presently he had both. At eight o’clock, with the skies clearing, another Catalina reported: “two battleships, one carrier afire [imaginary: the last enemy carrier had sunk three hours before] and three heavy cruisers, speed 12.” Their position, far to the northwest, was beyond Spruance’s range, but he headed out and waited for his superior speed to narrow the gap. No further reports came in, however, and as the day wore on, Spruance felt that the morning position was growing “rather cold.” It was the best target offered, though; and at 3:00 p.m., when he had closed to an estimated 230 miles, he began to launch.

A group of Enterprise dive bombers searched for 265 miles while a Hornet group searched 315 miles on a slightly different bearing. By now the weather had worsened. Each group found one small ship—the same one, a straggling destroyer; each attacked it unsuccessfully; and each lost a plane—the Enterprise to anti-aircraft, the Hornet to fuel exhaustion. The weary rest landed in darkness. Disheartened, Spruance set a westward course, although the empty ocean ahead promised little for next day, especially since he had to slack off his full-speed pursuit—his destroyers were low on fuel—and there was always the possibility of a night ambush by fast battleships. Still, luck might bring him across those two lame cruisers. He ordered the Enterprise to send a dawn search over the whole western semicircle.

The Kumano and Suzuya had taken no part in defending their sister against the Marines; they merely stood by a few miles away, and when Fleming’s crash further reduced the Mikuma’s speed, they increased their own and fled. Through the fifth and the early hours of the sixth, the cripples limped on with their two loyal destroyers. Their plight was desperate; they knew it, and Spruance soon learned it. The Enterprise’s scouts spotted them at 7:30 and shouted their position. The Hornet began to launch her dive bombers and fighters at 7:57. They struck at 9:50, and as they returned, the Enterprise launched. They, too, struck and returned, and the Hornet launched again.

In all, the Dauntlesses dropped eighty-one bombs. Five hit the Mogami, killing more than one hundred men. Ten gutted the Mikuma. Her survivors climbed aboard the destroyer Arashio, where a direct hit killed nearly all of them. Another bomb burst open the second destroyer’s stern. Between bombings, the Wildcats spattered the burning bulks with .50-caliber bullets. The last planes, racks empty, headed home at 3 p.m. The Mikuma sank about two hours later. The Mogami and the two destroyers, all afire, their broken decks littered with dead men, made their painful way back to Japan.

Spruance’s fuel was almost gone; enemy submarines were prowling the area, and further pursuit would take him within range of Wake, which was packed with Japanese planes once expected to base at Midway. He reversed course and withdrew toward his tankers. As his pilots stripped off their flight gear and relaxed, the Fortresses made their final attack—and Midway’s. Flying at 10,000 feet, they dropped their bombs on a vessel which they reported as “a cruiser that sank in fifteen seconds.” The “cruiser” proved to be the USS Grayling, a submarine. Happily, her sinking was only a crash dive.

Midway’s fighting was done, but its work was not—the work that had begun early on 4 June, when the first American pilot parachuted from his flaming plane. All that day, the next, and for weeks afterward, Catalinas searched the ocean for rafts and life jackets. They found Ensign Gay on the afternoon of the fifth. A medical officer asked what treatment he had given his wounds.

Gay said, “Soaked ’em in salt water for ten hours.”

On the sixth, they picked up another pilot, a lieutenant (jg) who had been clutching the bullet holes in his belly for two days. The Japanese had strafed him in his raft—to prove it, he brought in his splintered paddle. The Catalinas rescued more than fifty men. Thirty-five were Japanese, from the Hiryu’s engine room. They had drifted thirteen days and some 110 miles.

The biggest aftermath job was salvaging the Yorktown. It started auspiciously. The destroyer Hughes, standing by her on the night of the fourth, rescued two wounded men, who had been overlooked when she was abandoned, and one of her fighter pilots, who paddled up in his raft. Early next morning, Captain Buckmaster and a working party of 180 returned with three other destroyers, and that afternoon a mine sweeper took her in tow for Pearl Harbor. Repairs crept as slowly as the Yorktown herself, but by noon of the sixth, jettisoning and counterflooding had begun to reduce her list, and with the help of the destroyer Hammann, lashed to her starboard side and supplying power and water, her fires were being brought under control. Then, at 1:35, a lookout sighted four torpedo wakes to starboard. The Hammann’s gunners opened fire, hoping to detonate the war heads, and her captain tried to jerk her clear with his engines, but nothing availed. One torpedo passed astern. One hit the Hammann. The other two hit the Yorktown. They were death blows for both ships.

Geysers of oil, water and debris spouted high and crashed down. The convulsive heave of the decks snapped ankles and legs. Stunned men were hurled overboard, then sucked into flooding compartments. The Hammann’s back was broken; she settled fast and sank by the head. Almost at once, her grave exploded. The concussion killed some of the swimmers outright; others slowly bled to death from the eyes and mouth and nostrils.

The Yorktown’s huge bulk absorbed part of the two shocks, but her tall tripod foremast whipped like a sapling, and sheared rivets sang through the air. The rush of water into her starboard firerooms helped counter her port list at first, but Buckmaster knew that she was doomed. Too many safety doors had been sprung, too many bulkheads weakened. He mustered the working party to abandon ship. A few did not appear—the torpedoes had imprisoned them in compartments now inaccessibly submerged. An officer phoned one compartment after another. When a voice answered from the inaccessible fourth deck, he asked, “Do you know what kind of a fix you’re in?”

“Sure,” said the voice, “but we’ve got a hell of a good acey-deucey game down here. One thing, though—”

“Yes?”

“When you scuttle her, aim the torpedoes right where we are. We want it to be quick.”

They did not need to scuttle her. Early the next morning, “she turned over on her port side”—in Buckmaster’s words—“and sank in three thousand fathoms of water, with all her battle flags flying.” As her bow slid under, men on the destroyers saluted.

So ended the Battle of Midway. The United States had lost a carrier, a destroyer, 150 planes and 307 men. Japan had lost four carriers, a heavy cruiser, 253 planes and 3500 men. It was a decisive American victory. Exactly six months after Pearl Harbor, naval balance in the Pacific was restored. It was also Japan’s only naval defeat since 1592, when the Koreans under Yi Sunsin, in history’s first ironclad ships, drove Hideyoshi’s fleet from Chinhai Bay.

Tactically, Japan’s sunken carriers and dead combat pilots—some one hundred of her finest, plus another 120 wounded—caused drastic changes in her whole naval establishment. To replace the carriers, she had not only to convert seaplane tenders, thereby curtailing long-range reconnaissance, but to rig flight decks on two battleships. The pilots could never be replaced.

Said Captain Hiroaki Tsuda, “The loss affected us throughout the war.”

Strategically, Midway canceled Japan’s threat to Hawaii and the West Coast, arrested her eastward advance and forced her to confine her major efforts to New Guinea and the Solomons. Moreover, her efforts were no longer directed toward expansion, but toward mere holding.

The initiative that Japan dropped, the United States picked up. We moved forward from the “defensive-offensive,” in Admiral Ernest J. King’s phrases, “to the offensive-defensive,” and thence to Tokyo Bay. What ended there had begun at Midway. Said Rear Admiral Toshitane Takata, “Failure of the Midway campaign was the beginning of total failure.”

Our commanders may have recognized it at the time, but they restrained their optimism. Immediately after the battle, Admiral Nimitz announced only that “Pearl Harbor has now been partially avenged. Vengeance will not be complete until Japanese sea power is reduced to impotence. We have made substantial progress in that direction.” Then his jubilation broke out in a pun: “Perhaps we will be forgiven if we claim that we are about midway to that objective.”

|

| Sent out from the Japanese fleet, a floatplane searches in vain for the American aircraft carriers, destroyer and cruisers located near Midway Islands. Painting, Oil on wood, by John Hamilton, 1975 |

|

| This Midway Island based PBY discovered part of the Japanese Fleet on 3 June 1942 setting the course of the battle. Painting, oil on wood, by John Hamilton, c. 1975. |

|

| Unable to recover from the Japanese Zeros on patrol, this torpedo bomber from USS Hornet is about to be consumed by fire and the sea. Painting, oil on wood, by John Hamilton, c. 1975. |

|

| Singled out for attack by aircraft from the Japanese carrier Hiryu, USS Yorktown underwent a severe attack. Painting, oil on wood, by John Hamilton, c. 1975. |

|

| After a successful attack on the Japanese Fleet, a Dauntless dive bomber returns to the fleet defending Midway Island. Painting, oil on canvas, by Sam Massette, c. 2000. |

|

| Battle of Midway. |

|

| Movements during the battle, according to William Koenig in Epic Sea Battles. |

|

| The aircraft that participated in the Battle of Midway. |

|

| A U.S. Army Air Force Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress being serviced on Eastern Island, Midway Islands, in late May or early June 1942. |

|

| A U.S. Army Air Force Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress on Eastern Island, Midway Islands, in late May or early June 1942. |

|

| A U.S. Army Air Force Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress taking off from Eastern Island, Midway Islands, in late May or early June 1942. |

|

| USS Vincennes (CA-44) at Pearl Harbor, circa 26-28 May 1942, prior to departing to take part in the Battle of Midway. A Curtiss SOC floatplane is in the left foreground. |

|

| A U.S. Navy Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina off Sand Island, Midway Islands, after having returned from a patrol in late May or early June 1942. |

|

| An injured or exhausted rescued U.S. Navy flight crew man is taken on a stretcher out of a Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina on Midway Islands, after the Battle of Midway in June 1942. |

|

| A U.S. Navy PT boat off Sand Island, Midway Islands, in May or June 1942. |

|

| U.S. Marine Corps Vought SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers of Marine scout bombing squadron VMSB-241 taking off from Eastern Island, Midway Atoll, during the Battle of Midway, 4-6 June 1942. |

|

| U.S. Marines of the 6th Defense Battalion on Sand Island, Midway Islands, in May 1942. |

|

| Eastern Island, Midway Islands, under attack from Japanese aircraft on June 4, 1942. |

|

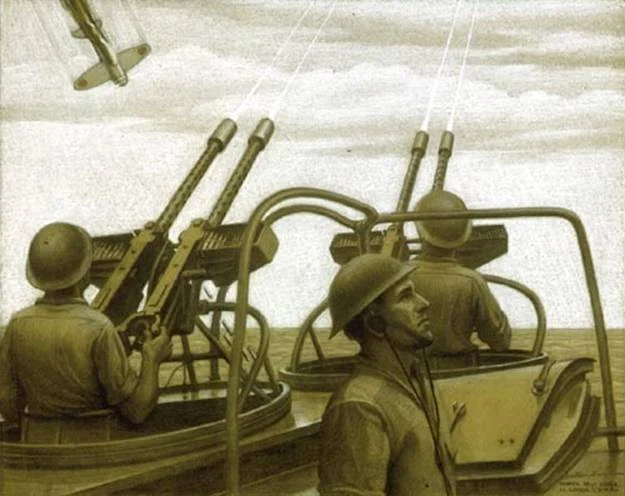

| A machine gun firing on Sand Island, Midway Islands, during Japanese air raid on June 4, 1942. |

|

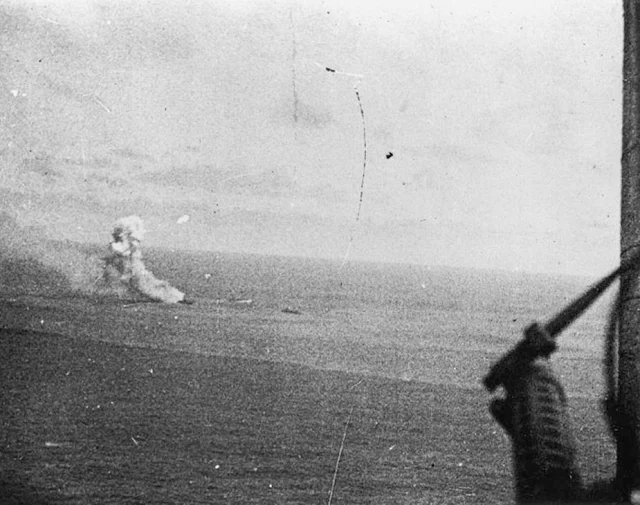

| Flak bursts around a Japanese plane attacking Midway Islands on June 4, 1942. |

|

| Three U.S. Marine Corps Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo fighters from Marine Fighting Squadron VMF-221 over Midway, in May/June 1942. |

|

| A burning oil tank on Sand Island, Midway Islands, after the Japanese air raid on June 4, 1942. |

|

| A burning oil tank on Sand Island, Midway Atoll, after the Japanese air raid on June 4, 1942. |

|

| The U.S. flag in front of burning oil tanks after the Japanese air raid on Sand Island, Midway Atoll, on June 4, 1942. |

|

| A burning building on Sand Island, Midway Islands, after the Japanese air raid on June 4, 1942. |

|

| Damage to the radio transmission building on Sand Island, Midway Atoll, following Japanese raid on 4 June 1942. |

|

| The burning seaplane hangar on Sand Island, Midway Islands, June 4, 1942. |

|