by Howard L. Oleck

Shock action is the basic aim of tanks in battle. Smashing, shattering, stunning attack is the main idea of any armored unit. Penetration, breakthrough, and a rampaging drive into the enemy rear is the ultimate purpose.

But always, whatever the mission of an armored unit, one emergency rule always holds true. Whatever the assigned mission may be, if enemy tanks are met the enemy tanks get top priority.

The reason for this Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) is simple. Tankers know that enemy tanks may do to their side what they aim to do to the enemy. Therefore, enemy tanks must be stopped. And the best answer to a tank attack is a counterattack, by tanks. The best way to stop a tank is with another tank.

A good example of this was the wide-open tank against tank fighting in the North African desert in World War II. The German attack at Faid Pass, and the American counterattack, were classics of tank warfare.

On 30 January 1943, the Germans’ 21st Panzer Division, newly equipped and freshly reinforced after the great battle of El Alamein, struck at Faid Pass in Tunisia, not far from Sidi bou Zid. In the mile-wide pass a small Free French infantry force, desperately holding the bastion on the Allied flank, reeled under the shock of the attack. The veteran German tankmen struck. While one tank column smashed into the pass, another flanking column swung around the northeast corner of the defensive position to hit it from the side.

At the same time, two other spearheads drove forward in wide circling arcs. One looped around the south of the pass, to take Faid village and cut off escape behind the pass. The other spearhead moved farther south to the high ground of the Djebel (Hill) bou Dzer, to follow up the attack with a breakthrough, or to flank any counterattacking force.

It was a “by-the-book” example of wily, powerful tank attack—a clever example of blitzkrieg tactics. Over the moving iron spearheads, Stuka dive bombers wheeled and circled, diving like black vultures at any strong point that slowed down the steadily advancing tank columns. Behind the tanks, in armored personnel carriers, panzergrenadiers (armored infantry) rode, ready to aid the tanks or to occupy captured positions.

Northeast of Sidi bou Zid lay the American 1st Armored Division, at Sbeitla. Urgent calls for help flashed to it from the hopelessly outclassed French unit in Faid Pass. The American division, still green, and still mostly untried, was ordered to counterattack. “Stop the German spearheads!” were the instructions.

Combat Command A (CCA) of the 1st Armored, led by Brigadier General Raymond McQuillin, moved out of bivouac, and started its steel column of roaring, clanking machines towards the east. As evening fell, this column halted near the western end of Faid Pass while reconnaissance scout cars moved gingerly forward, feeling for the enemy.

At the same time Combat Command C (CCC) started forward, led by Colonel Robert I. Stack, east of the Sidi bou Zid area. This column was to hit any advancing enemy force on its flank at Maizila Pass south of Faid Pass, and to stop it with a head-on smash, or by crossing the “T.”

Tank tactics in open country are like naval tactics. Each side tries to “cross the T.” That means that each column wants to cut directly across the line of advance of the enemy column. That way, the crossing column’s tanks can concentrate their fire on the leading enemy tank, and pound it to death. The outmaneuvered column finds that its own tanks are in its line of fire, and they interfere with each other.

A third counterattack column from 1st Armored Division, Combat Command D (CCD), led by Brigadier General Robert Maraist headed south, too. It moved through Gafsa, over 80 miles below Faid Pass, to attack Sened and Sened Station while the Germans were busy. That way, it could seize a valuable base, and threaten to make a huge flanking run from the south. CCB remained behind, in reserve.

That was the “big picture” plan of the Americans. Next step was the actual, close-in “tactical” clash. At three o’clock in the morning of 31 January, McQuillin sent a task force led by Colonel Alex Stark to meet the advancing panzers at the western exit from Faid Pass. Another group (Task Force Kern) was to swing a little south and hit the main enemy advance from that direction.

Stark’s task force had hoped to move up a trail above Faid, and then swarm down into the pass where the French unit had been obliterated.

But the Germans had not been idle during the night. They had made hasty but formidable preparations for the oncoming American counterattack.

Mine fields had been sewn in the area where the hill rises began. In the pass itself several German tanks had been placed behind rocks and in hollows, in defilade, with their guns aimed west.

Panzergrenadiers had dug in below the slope and on it, in foxholes, and slit trenches. Heavy anti-tank guns (the deadly “88s”) had been skillfully sited on the slopes. Heavy machine guns and mortars also had been emplaced. From the hillsides, they had perfect observation.

The German plan was to hold the hill masses on both sides of the pass in a solid grip. Then, through the pass, the panzer columns could strike out like coiled snakes, led by huge Tiger tanks. In the morning the columns of German armor started to move east, out of the pass. Any American counterattack was bound to suffer heavily from the concealed anti-tank guns, as well as from the panzers themselves.

Stark’s column advanced toward the pass. Company H, First Armored Regiment, led the dangerous counterattack against the ominous hills and pass.

Stark ordered the 91st Armored Field Artillery Battalion to halt its self-propelled guns just within good range of the pass. Accompanying armored infantry carriers followed the tanks.

Then, one by one, the attacking tanks ran into just about every possible enemy defensive device. First was a mine field. Continuing in column, the tanks passed through the deadly zone in single file. Fortunately, no tank had its tracks broken by the light anti-personnel mines. Column formation is best for passing through a mine field. Each tank follows the path of the one ahead of it. Cracking eruptions of the land mines, that would have torn a man to pieces, did not halt the big M4 Shermans.

Once through the mine field, the tanks shifted into line for attack, as small arms fire from German infantry began to drum on their armor. In a long assault wave, they rolled forward, right over the foxholes. This was shock assault against infantry—a cinch for tanks. Behind the machines, armored infantrymen followed, to capture or finish off those Germans who did not break and run. So far, so good.

Beyond the light infantry defense line, the tanks shifted formation again. This time they moved in “V” formation—a line of “Vs”—five tanks (one platoon) in each “V.” From this formation they could most quickly shift into either line, column, or echelon.

Near the foot of the first hill, a storm of German anti-tank gun fire blazed out at the approaching “Vs.” Normally, tanks avoid running up so close to dominating positions where anti-tank guns are likely to be concealed. But the mission called for it, and they moved forward. From the turrets of the Shermans their 75s spat back at the “88s” concealed in groves of trees up on the slope.

Once a strong enemy position is located, tank tactics call for a basic maneuver called “fire and movement.” One group of tanks (two tanks out of a five-tank platoon; or one platoon out of a three-platoon company) stop and form the “base of fire.”

The “base of fire” tanks take defilade position, if there is any cover behind which to halt. In “defilade,” only the tank’s turret and gun are exposed to enemy fire, while the hull is hidden by the rise of earth in front. If no cover is available, the “base of fire” tanks simply stop, or slow down. Then they can fire more accurately. Their job is to engage the enemy in a fire-fight, while the other tanks move up.

The “movement” group usually swings around the enemy position in order to attack it from the flank. But at Faid Pass the whole hill mass was full of enemy guns and troops. More important, the mission of the task force was not to get involved in aimless fights. Its job was plain—to stop the exit from Faid Pass, put a cork in the bottleneck, and stop the threatened drive of German panzer columns out.

So, while a platoon of mediums stopped, and dueled with the anti-tank guns up the hill, the other platoons ranged themselves into a new formation—echelon formation, heading south towards the exit from the pass.

In echelon formation, all tanks could fire straight ahead, towards the pass, without blocking each other. At the same time, by turning their turrets to the left they could fire at the anti-tank guns on the hill. Also, if one tank is hit and stopped in an echelon movement, it does not block the advance of the others. They close up the gap and keep moving.

Just so, the counterattacking column raked the hillside to the east as it went by, rolling south. At the same time, they called back to their artillery, over the radios, for bombardment of the hill positions. Once artillery fire started to pound the anti-tank gun positions on the hill, the tanks could concentrate on the pass.

At that moment, the panzer columns started to emerge from the pass. In two parallel columns, the big German tanks streamed out towards the plain. Like two fleets at sea, the two hostile groups of fighting machines approached each other.

A deadly race began—the stakes were literally victory or death. The one that managed to cross the “T” of the other would have a fearful advantage.

Dust and smoke boiled up as the spinning tracks kicked up sand on the hard ground. The plain and pass reverberated with the shattering roars of powerful engines and the hellish clatter of tortured steel. That most terrible of all modern war’s spectacles was about to begin—the clash of tanks against tanks, steel against steel, in an earth-shaking battle of giants.

Inside the tanks, sweating men strained to push big shells up to steaming cannon. Drivers pulled open throttles on engines already bellowing at full speed. Tank commanders peered through periscopes and snapped ranges and fire commands to their gunners. One after another, in both groups of tanks, the big guns began to crack and roar.

The American commander spoke quietly into his radio mike. “Shift formation! All tanks change formation! Take column formation!”

The echelon shifted into column, as the tanks rocked and lurched ahead. All guns started to bear left, straight at the approaching panzer columns.

In the German tanks, cold sweat beaded the brows of the tank commanders. The American Shermans were faster. The Americans were going to cut right across the German columns—to cross the “T.” Frantic calls for help crackled back to the Luftwaffe planes.

The planes came swiftly. But it was too late. Right across—in front of the panzer columns, the racing Shermans streamed. Their 75s raked the big German tanks as they passed. One after another the panzers shuddered and veered as armor-piercing shells smashed into them. Then the panzer columns turned hastily, and wheeled around, back towards the pass. Behind them they left the flaming wrecks of their tanks.

In the triumphant American column, shells struck the Shermans, too. Disabled tanks cluttered the field.

Overhead, Messerschmitt Me 109s darted, strafing the armored infantry behind the tanks, preventing the GIs from storming into the pass. Then Ju 87s came over, bombing and machine-gunning the Americans, forcing the supporting artillery to take cover.

The Shermans were unharmed by the air attack. But without their supporting infantry and artillery they would have been mad to enter the pass in pursuit. The column turned away and rolled back west.

“Mission accomplished!” Radio messages flashed back to the division command post. The panzers had been stopped—at a price. Several American tanks were lost—but they had been victorious nevertheless. Every trick in the book had been used—every tactical formation—in the wild battle. The panzers had been beaten.

The story was much the same in all the three combat commands. The German advance was stopped.

Far to the south, CCD swung around Sened, beat off the Germans there, and captured Sened Station. At Maizila Pass, in another swirling run, CCC cut right across the exit from that pass, turning back the panzer column that tried to burst out.

In the south, the defeated Germans pulled back to Maknassy to lick their wounds. At Maizila Pass and Fair Pass they backed into their prepared positions. Their dream of a smashing breakthrough had ended.

`It was not a full victory. The Americans had advanced only at Sened, and not at the two passes. But they had met and frustrated the best the Afrika Korps and panzer columns could throw at them.

Even more important, the Americans had tested and proved their tank tactics in the fiery crucible of battle. In the open battleground of North Africa’s deserts and hills, the tactics of the GIs had won out over the tough, experienced German desert tank columns.

From these battles the Yanks garnered the “know-how” that eventually would win the greatest war in history. At the cost of burning tanks and dead and wounded men—the inevitable price of war—they learned once and for all “how to do it.”

So ended the greatest German tank attack of Faid Pass, under the smashing counterattack of an American tank column. The war was still far from over. But the Americans were on the right track, in terms of men, equipment, and tactics—and they knew it.

|

| The Battle of Faid Pass. |

|

| American 37 mm anti-tank Gun (M3A1) and crew wait for the expected enemy column through Faïd Pass, 14 February 1943. |

|

| German 17 cm K18 gun in action in Tunisia, 1943. |

|

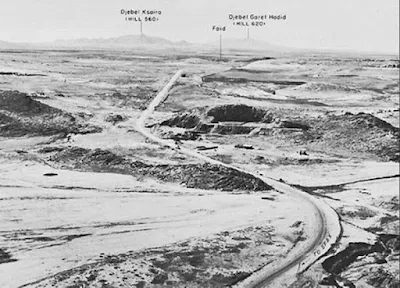

| Faïd Pass, looking southwest. |

|

| Burning knocked out M4 medium tank examined by German troops. |

No comments:

Post a Comment