by Don Dwiggins

Published in December 1969

And so there I am on Sunday morning, flying this tired P-40 in my tuxedo pants and a skivvy shirt, right inside a pack of jittery Japs strafing Ewa Marine Base next to Pearl Harbor, unshaven, a little hung-over. I sneak in behind this Val, get him in my sights and start shootin’. I am absolutely amazed at how quickly he folds up. Bingo! A ball of fire! Then I pull up, onto another one…”

The general is talking over his shoulder from the left seat of a slick, new Piper Cherokee 140 he is flying around the island, reliving the utterly preposterous thing that happened to him twenty-eight years ago, 7 December 1941, a terror-laden Sunday morning that heaved world history into chaos.

He chews hard on an unlit cigar, the muscles in his jaw rippling, sweat beading his face. He flies with consummate, unstudied skill, though he’s never piloted a Cherokee before. He jabs the cigar dead ahead, stretching his neck to see better.

“Down there! Look down there! At what’s left of Haleiwa! The strip I took off from!” General Kenneth M. Taylor, a little heavier now, hair thinning, but real cool, hunches forward, knuckles white on the wheel, his neck corded. With a gut-sucking wrench, he slams the Cherokee hard over into a vertical bank, the wingtip seeming to drag through tall palms lining a barren gash and then across the foaming surfline on Oahu’s Windward Coast.

In the right seat, Bud Weisbrod, hulking operator of Hawaii’s Island Flight Center, cringes noticeably. It’s his airplane. “The general,” he says matter-of-factly, “is doing his thing.”

Taylor’s eyes squint, and they are no longer the eyes of a middle-aged brigadier general, Assistant Adjutant General (Air), Alaska, holder of the Distinguished Service Cross, Legion of Merit, Air Medal, Purple Heart and other hardware.

They are the gray-green eyes of Second Lieutenant Ken Taylor, prize hotshot of the Army Air Force’s 47th Fighter Squadron, 15th Fighter Group, one of only two fighter outfits in the Territory on Pearl Harbor Day. A little bloodshot from a Saturday night of hell-raising, but steady, puzzling over a funny-looking B-17 with a strange tail, unlike the Fortresses he’d seen at Hickam.

Lieutenant Taylor tests his guns, a pair of .30-caliber machine guns in each wing, two fifties in the nose, heaviest armament in service. Tracers spit forward. He wags his wings to signal his wingmate, Lt. George Welch. Together, they are the only two combat-ready fighters in the sky to attack the invaders.

“We drive up pretty close,” he relates. “One of us on each side. We are ready to turn in for the kill, but we see a bunch of guys inside, jumping around and waving. We pull away. They’re on our side. One of Maj. Truman Landon’s new ships, just arriving from the mainland.

“I crank the coffee grinder to George’s frequency and we chat a bit. ‘What do you think, George? We doing the right thing?’ Remember, this is our first war, and we aren’t sure we’re not making a horrible mistake.

“That’s when we run down to Ewa, where all the action is, and slip into the circle of Vals. We get on the tail end and go to work. Our guns are bore-sighted for six hundred feet, so we start in shootin’ at seven hundred.

“After I flame the first one, I line up on this next character, and I’m hitting him but he’s not burning. His rear gunner is shooting at me and that makes me very mad. I put him out of action. I see flames, and he heads out to sea, trying to get back to the carrier. He doesn’t make it.”

Right here is where one of the ironies of war makes it tough for Taylor to verify his claim to being America’s first ace of World War II. He had no gun camera, hence the Japanese planes he and George Welch sent to the bottom of the ocean during the Pearl Harbor holocaust weren’t counted officially. Later, when it was learned that the Japanese lost twenty-nine aircraft in the raid, the government credited four kills each to the two lieutenants.

Of course, things haven’t changed a hell of a lot in twenty-eight years. When Bud Weisbrod and a friend, Professor Martin Vitousek, from the University of Hawaii, fly up to Wheeler Field to pick up Gen. Taylor and me, they cannot land. Somebody forgot to tell the brass they were coming.

“Security here is tighter than in forty-one,” Taylor comments dryly.

We have to drive back down to Honolulu International to meet them. It was there, incidentally, that Vitousek, as a boy of seventeen, got airborne in an Aeronca, flying with his dad, just in time to watch Pearl Harbor explode. A sight that scars his mind today.

The occasion for this get-together of old Pearl Harbor hands is a movie—Twentieth Century-Fox’s “Tora! Tora! Tora!”—a $25,000,000 sham battle so damnably real it had sailors diving overboard and jittery Fox Air Force pilots trying too hard to sink dummy battleships with Plexiglas bombs. When you try too hard, you die. Two did.

Flying over the island of Oahu, I am privy to their psychological vibrations as Taylor and Vitousek flash back across three decades, remembering what it was like. A junk-pile Japanese Zero flashes by, streaking for Hickam Field. Taylor grimaces.

“Over there … in that pineapple plantation … that’s where I flamed one,” he is saying.

Nothing there today. Just miles and miles of pineapples.

Back at the Ilkai bar, we talk over a maitai, about how the Japanese finally took the city by buying it.

“It’s changed quite a bit,” Taylor says.

He was young and in love and a hell-raiser in general, who often buzzed the town on Sunday mornings “to wake up the Navy.”

“George and I were permanent ODs,” Taylor grins over his maitai.

Saturday night, 6 December 1941: Pearl Harbor is invulnerable, and the P-40s at Wheeler are safely parked tail to tail in mid-field, safe from saboteurs. Taylor and a buddy, Lt. Charley Parrot, go out on the town together.

“We hit a Chinese place—Laui Chi’s—where the officers hung out. You had to dress for dinner. White coat, black tie. We were ready for whatever came along.”

The girl he hoped would come along didn’t show up—Flora Love Morrison, a good-looking girl from Hennessey, Oklahoma, near his home town of Enid, living with her father, who worked at Pearl. A girl he would later marry, and call Baby because she has this pretty baby face.

“We drifted over to the Officer’s Club at Hickam, in a group. I had a date with a gal named Maxine, who later married Charley Parrot. The usual Saturday night … drinks, talk, dancing. Then back to Wheeler. I wanted to sit in on the poker game that ran every Saturday night. There were some mighty good players there.”

“This colonel—his name was Flood—asked how I could play in such a big game on my salary. It was no problem, I told him, since the first game, because I was playing on his money.”

Midnight passes, and as the world remembers, the predawn hours trickle out to end an era, while offshore, in a biting wind, Capt. Mitsuo Fuchida, air group commander of the Japanese Imperial Navy’s carrier Akagi, waits impatiently for dawn.

The Wheeler Field BOQ is a rambling stucco building surrounding a patio. Sleeping quarters line two sides, and an entrance lobby, bar and dining-dance area the others. Lieutenant Taylor is winning at poker, but not so much he can’t leave the game. He cashes in his chips, yawns and heads for the sack.

It’s been a busy week for Ken Taylor. The 47th Fighter Squadron had flown down to Haleiwa for routine air-to-air gunnery practice, shooting up tow targets. He and George Welch were among the 47th’s top scorers.

Taylor turns in. The sack feels good. No weekend flying. Tomorrow, Sunday, will be just another easy day.

Explosions jar the BOQ. Taylor sits bolt-upright. It’s daylight, not yet light. He runs to the window. More bombs explode, slugs rip through the BOQ patio.

He grabs his pants and a skivvy shirt and runs outside. He meets Welch. They stare in amazement. Japanese planes are strafing Wheeler. The rows of P-40s, all neatly parked in mid-field, are burning, belching black smoke. More Japanese planes come in, lining up for their strafing runs, right over the BOQ.

“Ken,” Welch says thoughtfully, “these guys are not friendly. Let’s go!”

Taylor thinks, well, maybe there’s gonna be one hell of a big court-martial. We’ve got no orders! (Captain Austin, the CO, is on another island, Hawaii.)

Taylor grabs a phone in the corridor, dodges bullets as more planes sweep in low, gets Haleiwa’s OD. “Warm up two ships!” he yells.

Moments later, they’re plunging down the ten miles of dirt road to Haleiwa, Ken’s brand-new 1941 Buick sedan raising a trail of dust. A Zeke comes for them. Ken swerves hard and the bullets miss. At Haleiwa, they leap out and run to their idling Warhawks, parked under palm trees. The Japanese somehow missed seeing the rows of fighters parked there.

Taylor and Welch roar down the runway, wingtip to wingtip, a formation takeoff to fly line abreast, a style of fighting thus born that would become SOP for the rest of the war.

“We didn’t plan it,” Taylor says over his maitai. “It just worked out best; we could guard each other’s tails that way.”

Again, that uneasy feeling that their necks are out a mile. They look over the stray B-17, then climb up under the cloud base at 3,000 and loaf down toward Pearl.

Battleship Row is a bloody, burning shambles. At Ewa it looks as if the Marines are getting off. They dive for Ewa, get a rude shock. The planes are Vals! George and Ken split, slip into the circle of orbiting planes and each shoot down two like sitting ducks. Taylor follows another out over the water, flames him good. Three kills, and his guns are empty.

Back at Wheeler, he finds Welch on the ground reloading. He sets down, taxis past the pyre of P-40s and stops alongside George. Ground crewmen frantically dart inside the burning hangars, wheel out boxes of ammo.

“People are jumping up on the wings, yelling at us to disperse! Disperse!” The general grins. “I take one look at those burning P-40s and shake my head. We’ve got the only flyable ships on the field. We get all kinds of advice. All bad.”

Concerned lest somebody might pull rank and swipe his ship, Lt. Taylor watches George leap off and then starts after him. An ammo dolly blocks his way. To hell with it! He guns the P-40. It bounces over the dolly. He swings out to take off into the south, just as a flight of Japanese comes in from that direction. His lips pull back. Rolling fast now, he holds the gunsight on the lead Japanese, while still on the ground. He squeezes the trigger.

“We pass with a great rush,” he says. “I’m sure I got some hits on him. I chandelle up into position behind another Japanese in the strafing line, and I have him smoking—but I make one mistake. I’ve chandelled right into the middle of the line. A slug comes through my canopy. Slivers dig into my leg.”

His head on a swivel, Taylor sees his buddy, George, knock off his attacker. He breaks off and pulls up into a cloud.

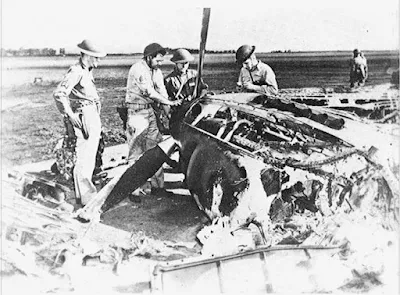

“George and I got two more out of that group. After a couple of hours, we landed at Wheeler, then went back to Haleiwa, where I got first aid.””Then they climb back into Ken’s Buick and drive toward Wheeler, to look over one of the wrecks.

“Suddenly we see Capt. Austin and the operations officer roaring down the road, the top on their convertible flying up and down. They pull out to block the road and we skid to a stop. Austin starts giving us one of his famous chewings. He ended by shouting, “If you don’t know there’s a war on, I’ll tell you bastards, there is! Now get to the field and do something about it!”

Lieutenant Taylor stammers, reddening, “But, sir,” he says, “your squadron, the Fighting 47th, has just distinguished itself!”

The CO’s mouth drops open and, the general remembers, “it was one time he was delighted with Taylor and Welch!”

Both pilots win the DFC and each are credited with two victories; later on, each officially is given four kills. Of the twenty-nine Japanese ships that did not return to the carriers, more than half cannot be attributed to anti-aircraft fire.

Taylor went on to finish the war in the South Pacific and run his total of official victories to six. In 1967, he retired from the Air Force and joined the Alaskan Air Guard as a brigadier general. George Welch later became a test pilot and was killed in a jet crash.

When Gen. Taylor and I drove out to Wheeler AFB recently, to watch Director Richard Fleischer direct a scene for “Tora! Tora! Tora!” wherein actors Carl Reindell and Rick Cooper reenact Taylor’s and Welch’s roles on Pearl Harbor Day, something went wrong. A radio-controlled P-40 went out of control on take-off, smashing into four parked Warhawks with a wild explosion.

The general nodded to Fleischer. “Yes, that’s the way it was. Like that.” [Note: The scene was filmed and put into the movie.—R.M.]

Later, I asked who was credited with shooting down the first enemy plane in World War II—he or George?

“No one will ever know,” he replied. “George and I separated over Ewa, remember. But we made a gentleman’s agreement. If one of us bought the farm, the survivor could claim it. George is dead now. That leaves me.

|

| Kenneth Taylor (shown here as a major, circa 1945) was a second lieutenant when he took off from blazing Wheeler Field and became the first World War II Yank to score an air kill. |

|

| Taylor receiving the Distinguished Service Cross on January 8, 1942 for his efforts. Note the tattered flag. |

|

| The tombstone of Kenneth M. Taylor at Arlington National Cemetery. |