At exactly 7:55 on a beautiful Sunday morning the United

States was suddenly plunged into the greatest conflict in the history of the

world. We were not only unprepared for war, but our armed forces in. the

Pacific were caught completely by surprise.

That same Sunday morning two young Army Air Corps

lieutenants were just leaving an all-night party at Wheeler Field, Hawaii. They

were George Welsh and Ken Taylor of the 15th Pursuit Group. As they stood

outside an army barracks watching the tropical dawn grow brighter, neither had

any idea of the momentous event which was about to change their lives. It was 7

December 1941. Welsh was saying that instead of going to sleep, he wanted to

drive back to their own base at nearby Haleiwa Field for a nice Sunday morning

swim.

At that moment, just ten miles south of Lieutenants Welsh

and Taylor, carrier-based dive bombers, torpedo planes and fighters of the

Imperial Japanese Navy were beginning their carefully planned sneak attack on

the great American naval base at Pearl Harbor, as well as its surrounding

airfields. Most of our powerful Pacific Fleet was in training, and there were

ninety-six United States warships anchored in and about this Pacific

stronghold. War had been expected by our military leaders, but the general

opinion was that the Japanese would open hostilities against the Dutch or

British possessions in Asia thousands of miles farther west.

As Welsh and Taylor walked to their car to head back to

their own base, they saw sixty-two new Curtiss P-40 “Tomahawks” parked wing tip

to wing tip so they could be guarded “against sabotage.”

Suddenly the Japanese swooped down on Wheeler Field, which

was a center for fighter operations in Hawaii. Dive bombers seemed to appear

out of nowhere. Violent explosions upended the parked planes, and buildings

began to burn.

Welsh ran for a telephone and called Haleiwa as bullets

sprayed around him.

“Get two P-40s ready!” he yelled. “It’s not a gag—the Japs

are here.”

The drive up to Haleiwa was a wild one. Japanese Zeros

strafed Welsh and Taylor three times. When the two fliers careened onto their

field nine minutes later, their fighter planes were already armed and the propellers

were turning over. Without waiting for orders they took off.

As they climbed for altitude they ran into twelve Japanese

Val dive bombers over the Marine air base at Ewa. Welsh and Taylor began their

attack immediately. on their first pass, machine guns blazing, each shot down a

bomber. As Taylor zoomed up and over in his Tomahawk he saw an enemy bomber

heading out to sea. He gave his P-40 full throttle and roared after it. Again

his aim was good and the Val broke up before his eyes. In the meantime Welsh’s

plane had been hit and he dived into a protective cloud bank. The damage didn’t

seem too serious so he flew out again—only to find himself on the tail of

another Val. With only one gun now working he nevertheless managed to send the

bomber flaming into the sea.

Both pilots now vectored toward burning Wheeler Field for

more ammunition and gas. Unfortunately the extra cartridge belts for the P-40s

were in a hangar which was on fire. Two mechanics ran bravely into the

dangerous inferno and returned with the ammunition.

The Japanese were just beginning a second strafing of the

field as Welsh and Taylor hauled their P-40s into the air again. They headed

directly into the enemy planes, all guns firing. This time Ken Taylor was hit

in the arm, and then a Val closed in behind him. Welsh kicked his rudder and

the Tomahawk whipped around and blasted the Val, though his own plane had been

hit once more. Taylor had to land, but George Welsh shot down still another

bomber near Ewa before he returned.

Perhaps twenty American fighter planes managed to get into

the air that morning—including five obsolete Republic P-35s. Most of them were

shot down, but their bravery and initiative accounted for six victories in the

one-sided aerial battle.

The United States possessed no airplane which could outfight

the Japanese Zero on its own terms. The Zero was faster—except in a dive. It

could out-turn the American fighter planes and it could out climb them. It was

the most important weapon Japan had until the Kamikaze planes were introduced

near the end of the war.

At first our pilots did not know the weaknesses of the

Zero—that it had no armor, that it had no self-sealing gasoline tanks, and that

its explosive 20-mm cannons did not have the range or accuracy of the smaller

but powerful .50-caliber machine guns mounted in our newest fighters. Also our

pilots had not yet perfected the principle of the wingman, who was trained to

stick close to his leader during combat and protect him from any attack from

the rear.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who was in charge of all Japanese

naval operations, had planned the Pearl Harbor strike brilliantly. In a few

hours all of the Navy and Marine aircraft at Ewa air base were destroyed on the

ground. Two-thirds of the Pacific Fleet was either sunk or seriously crippled.

Luckily our two aircraft carriers in the South Pacific, the Lexington and the

Enterprise, were away from Pearl Harbor during the attack.

The Japanese particularly wanted to catch our carriers in

the harbor. Admiral Yamamoto knew the value of the carrier better than most

naval commanders. As early as 1915 he had stated that: “The most important ship

of the future will be a ship to carry airplanes.” (After the war we learned

that most of the messages sent from Pearl Harbor by a Japanese spy had to do

with the whereabouts of our carriers.)

The Enterprise didn’t escape entirely, however. She was on

her way back to Pearl Harbor after delivering Major Paul Putnam’s squadron of

Marine Grumman F4F “Wildcats” to Wake Island. Heavy seas had kept the “Big E”

from arriving on time—which would have meant her destruction. But many of her

scouts and bombers which flew in ahead of the ship were caught in the initial

Japanese attack, and five were lost.

Even more tragic was the fate suffered by Navy Lieutenant

Fritz Hebel. He was leading his Wildcat fighters from the Enterprise toward

Ford Island in Pearl Harbor later that day after completing a search mission.

It was 7:30 and getting dark. The men on the ground were still jittery from the

morning attacks. As Hebel’s fighters came in for a landing the whole sky

suddenly filled with tracer bullets. Practically every ship in the harbor

thought the Wildcats were Japanese planes returning for another raid.

Lieutenant Hebel and three other Navy pilots were killed by our own guns.

|

| A flight of six Curtiss-Wright P-40B Warhawks of the 44th Pursuit Squadron, 18th Pursuit Group, over the island of Oahu, Territory of Hawaii, 9:00 a.m., 1 August 1941. |

|

Maj. George S. Welch poses with his P-40 aircraft while assigned to the 45th Air Base Group in

Hawaii. |

|

| Lieutenants Kenneth Marlar Taylor and George Schwartz Welch, Air Corps, United States Army. Taylor and Welch took two Curtiss-Wright P-40B Warhawk fighters from a remote airfield at Haleiwa, on the northwestern side of the island of Oahu, and against overwhelming odds, each shot down four enemy airplanes: Welch shot down three Aichi D3A Type 99 “Val” dive bombers and one Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 (“Zero”) fighter. Taylor also shot down four Japanese airplanes. |

|

| The Curtiss P-36A Hawk in the World War II Gallery at the National Museum of the United States Air Force features a mannequin of a pajama-clad 2nd Lt. Philip M. Rasmussen. |

|

| The few who got up: (L-R) Pearl Harbor fighter pilots 2nd Lt. Harry Brown, 2nd Lt. Philip M. Rasmussen, 2nd Lt. Kenneth M. Taylor, 2nd Lt. George S. Welch, and 1st Lt. Lewis M. Sanders. |

|

| (L-R) Pearl Harbor fighter pilots 1st Lt. Lewis M. Sanders, 2nd Lt. Philip M. Rasmussen, 2nd Lt. Kenneth M. Taylor, 2nd Lt. George S. Welch, and 2nd Lt. Harry Brown. |

|

| Welch and Taylor during the awards ceremony for their Distinguished Service Cross medals. Welch was nominated for the Medal of Honor but was rejected because he acted without orders to take off'. |

|

| Lieutenant George S. Welch, of Wilmington, Delaware, gets a hearty handshake from President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House in Washington, May 25, 1942 and his congratulations for shooting down four Japanese planes during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7. From left to right are Sen. James H. Hughes (D-Del.), Mrs. Hughes, Mrs. George Schwartz, Welch's mother; George Schwartz, his stepfather, and Lieutenant Welch. |

|

| George Welch. He would end World War II with 16 total confirmed enemy airplanes shot down. A test pilot post-war, he died of injuries from a plane crash sustained during a test flight of the F-100. |

|

| Burial, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Arlington County, Virginia. Plot: Section 6, Grave 8578-D. |

|

| Rasmussen beside damaged P-36 Hawk. Philip M. Rasmussen (May 11, 1918 – April 30, 2005) was a United States Army Air Forces second lieutenant assigned to the 46th Pursuit Squadron at Wheeler Field on the island of Oahu during the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941. He was one of the few American pilots to get into the air that day. Rasmussen was awarded a Silver Star for his actions. He flew many later combat missions, including a bombing mission over Japan that earned him an oak leaf cluster. He stayed in the military after the war and eventually retired from the United States Air Force as a lieutenant colonel in 1965. He died in 2005 of complications from cancer and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. |

|

| Curtiss P-36A Hawk, at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, in the markings of the aircraft flown by Rasmussen during the Pearl Harbor attack. |

|

| Wrecked P-40 and hangars at Wheeler Field. |

|

| Another casualty of the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor. This photograph was taken seconds after the plane exploded. |

|

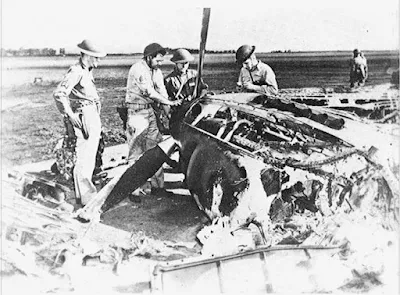

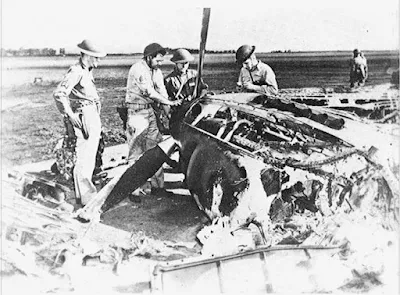

| Resourceful aircrews remove parts from a P-40 destroyed in the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Wheeler Air Base for us on other repairable aircraft. |

|

| Wrecked planes at Wheeler Field after the 7 December attack. Of the Army's 123 first-line planes in Hawaii, 63 survived the attack; of the Navy's 148 serviceable combat aircraft, 36 remained. |

|

| The remains of a P-40 Tomahawk at Wheeler Field. |

|

| A heavily damaged U.S. Army Air Forces Curtiss P-40 from the 44th Pursuit Squadron at Bellows Field, Territory of Hawaii, after the Japanese attack on 7 December 1941. |

|

| P-40 Warhawk aircraft damaged in a taxiing accident with another P-40 at Bellows Field, 8 December 1941. Is this the aircraft that was in the accident with the P-40 in the previous photo? |

|

| Remains of P-40s caught on the ground during the attack. |

|

| The first bombs to strike Hickam Field Dec. 7, 1941 were dropped on Hawaiian Air Depot buildings and the hangar line, causing thick clouds of smoke to billow upward. |

|

| Members of the Hawaiian Air Force's Headquarters Squadron, 17th Tow Target Squadron and 23rd Materiel Squadron watch Japanese high-Ievel horizontal bombers heading toward Pearl Harbor Dec. 7, 1941. |

|

| Airmen with other personnel man a gun emplacement set up in a bomb crater between Hangars 11-13 and 15-17, Hickam Field, Dec. 7, 1941. |

|

| Construction work at Wheeler Field on 11 December 1941. After the Japanese raid many destroyed or damaged buildings were rebuilt. |

|

| USAAF Curtiss P-40B (s/n 41-13297, c/n 16073). This aircraft survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 as it was in a maintenance hangar undergoing repair. The plane was wrecked on 24 January 1942 while on patrol over Koolau Range, Oahu, when it spun in. The pilot was killed. |

|

| The former USAAF Curtiss P-40B (s/n 41-13297, c/n 16073) in flight. The wreck was recovered between 1985 and 1989 and restored by the Curtiss Wright Historical Association, using parts from aircraft 39-285 and 39-287. It was later sold to "The Fighter Collection" at Duxford, UK. |

|

| Wheeler Army Air Field, Hawaii: Soldiers from B Company, 209th Aviation Support Battalion push a Curtis P-40 Warhawk into position near Wheeler's Kawamura gate. The static display used in the movie "Tora, Tora, Tora" was recently refurbished by the soldiers. 12 June 2008. |

No comments:

Post a Comment