The start of the war in Europe is generally held to be 1

September 1939, beginning with the German invasion of Poland; Britain and

France declared war on Germany two days later. The dates for the beginning of

war in the Pacific include the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War on 7 July

1937, or even the Japanese invasion of Manchuria on 19 September 1931.

Others follow the British historian A. J. P. Taylor, who

held that the Sino-Japanese War and war in Europe and its colonies occurred

simultaneously and the two wars merged in 1941. This article uses the

conventional dating. Other starting dates sometimes used for World War II

include the Italian invasion of Abyssinia on 3 October 1935. The British

historian Antony Beevor views the beginning of the Second World War as the

Battles of Khalkhin Gol fought between Japan and the forces of Mongolia and the

Soviet Union from May to September 1939.

The exact date of the war's end is also not universally

agreed upon. It was generally accepted at the time that the war ended with the

armistice of 14 August 1945 (V-J Day), rather than the formal surrender of

Japan (2 September 1945). A peace treaty with Japan was signed in 1951 to

formally tie up any loose ends such as compensation to be paid to Allied

prisoners of war who had been victims of atrocities. A treaty regarding

Germany's future allowed the reunification of East and West Germany to take

place in 1990 and resolved other post-World War II issues.

Background

Europe

World War I had radically altered the political European

map, with the defeat of the Central Powers—including Austria-Hungary, Germany

and the Ottoman Empire—and the 1917 Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia, which

eventually led to the founding of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the victorious

Allies of World War I, such as France, Belgium, Italy, Greece and Romania,

gained territory, and new nation-states were created out of the collapse of

Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman and Russian Empires.

To prevent a future world war, the League of Nations was

created during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The organization's primary

goals were to prevent armed conflict through collective security, military and

naval disarmament, and settling international disputes through peaceful

negotiations and arbitration.

Despite strong pacifist sentiment after World War I, its

aftermath still caused irredentist and revanchist nationalism in several

European states. These sentiments were especially marked in Germany because of

the significant territorial, colonial, and financial losses incurred by the

Treaty of Versailles. Under the treaty, Germany lost around 13 percent of its

home territory and all of its overseas colonies, while German annexation of

other states was prohibited, reparations were imposed, and limits were placed

on the size and capability of the country's armed forces.

The German Empire was dissolved in the German Revolution of

1918–1919, and a democratic government, later known as the Weimar Republic, was

created. The interwar period saw strife between supporters of the new republic

and hard-line opponents on both the right and left. Italy, as an Entente ally,

had made some post-war territorial gains; however, Italian nationalists were

angered that the promises made by Britain and France to secure Italian entrance

into the war were not fulfilled with the peace settlement. From 1922 to 1925,

the Fascist movement led by Benito Mussolini seized power in Italy with a

nationalist, totalitarian, and class collaborationist agenda that abolished

representative democracy, repressed socialist, left-wing and liberal forces,

and pursued an aggressive expansionist foreign policy aimed at making Italy a

world power, promising the creation of a "New Roman Empire."

Adolf Hitler, after an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the

German government in 1923, eventually became the Chancellor of Germany in 1933.

He abolished democracy, espousing a radical, racially motivated revision of the

world order, and soon began a massive rearmament campaign. It was at this time

that political scientists began to predict that a second Great War might take

place. Meanwhile, France, to secure its alliance, allowed Italy a free hand in

Ethiopia, which Italy desired as a colonial possession. The situation was

aggravated in early 1935 when the Territory of the Saar Basin was legally

reunited with Germany and Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles,

accelerated his rearmament program, and introduced conscription.

Hoping to contain Germany, the United Kingdom, France and

Italy formed the Stresa Front; however, in June 1935, the United Kingdom made

an independent naval agreement with Germany, easing prior restrictions. The

Soviet Union, concerned by Germany's goals of capturing vast areas of eastern

Europe, drafted a treaty of mutual assistance with France. Before taking effect

though, the Franco-Soviet pact was required to go through the bureaucracy of

the League of Nations, which rendered it essentially toothless. The United

States, concerned with events in Europe and Asia, passed the Neutrality Act in

August of the same year.

Hitler defied the Versailles and Locarno treaties by

remilitarizing the Rhineland in March 1936. He encountered little opposition

from other European powers. In October 1936, Germany and Italy formed the

Rome–Berlin Axis. A month later, Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern

Pact, which Italy would join in the following year.

Asia

The Kuomintang (KMT) party in China launched a unification

campaign against regional warlords and nominally unified China in the

mid-1920s, but was soon embroiled in a civil war against its former Chinese

communist allies. In 1931, an increasingly militaristic Japanese Empire, which

had long sought influence in China as the first step of what its government saw

as the country's right to rule Asia, used the Mukden Incident as a pretext to

launch an invasion of Manchuria and establish the puppet state of Manchukuo.

Too weak to resist Japan, China appealed to the League of

Nations for help. Japan withdrew from the League of Nations after being

condemned for its incursion into Manchuria. The two nations then fought several

battles, in Shanghai, Rehe and Hebei, until the Tanggu Truce was signed in

1933. Thereafter, Chinese volunteer forces continued the resistance to Japanese

aggression in Manchuria, and Chahar and Suiyuan. After the 1936 Xi'an Incident,

the Kuomintang and communist forces agreed on a ceasefire to present a united

front to oppose Japan.

Pre-war Events

Italian Invasion of Ethiopia (1935)

The Second Italo–Abyssinian War was a brief colonial war

that began in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war began with the

invasion of the Ethiopian Empire (also known as Abyssinia) by the armed forces

of the Kingdom of Italy (Regno d'Italia), which was launched from Italian

Somaliland and Eritrea. The war resulted in the military occupation of Ethiopia

and its annexation into the newly created colony of Italian East Africa (Africa

Orientale Italiana, or AOI); in addition, it exposed the weakness of the League

of Nations as a force to preserve peace. Both Italy and Ethiopia were member

nations, but the League did nothing when the former clearly violated the

League's own Article X. Germany was the only major European nation to support

the invasion. Italy subsequently dropped its objections to Germany's goal of

absorbing Austria.

Spanish Civil War (1936–39)

When civil war broke out in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini lent

military support to the Nationalist rebels, led by General Francisco Franco.

The Soviet Union supported the existing government, the Spanish Republic. Over

30,000 foreign volunteers, known as the International Brigades, also fought

against the Nationalists. Both Germany and the USSR used this proxy war as an

opportunity to test in combat their most advanced weapons and tactics. The

bombing of Guernica by the German Condor Legion in April 1937 heightened

widespread concerns that the next major war would include extensive terror

bombing attacks on civilians. The Nationalists won the civil war in April 1939;

Franco, now dictator, bargained with both sides during the Second World War,

but never concluded any major agreements. He did send volunteers to fight on

the Eastern Front under German command but Spain remained neutral and did not

allow either side to use its territory.

Japanese Invasion of China (1937)

In July 1937, Japan captured the former Chinese imperial

capital of Beijing after instigating the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which

culminated in the Japanese campaign to invade all of China. The Soviets quickly

signed a non-aggression pact with China to lend materiel support, effectively

ending China's prior co-operation with Germany. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

deployed his best army to defend Shanghai, but, after three months of fighting,

Shanghai fell. The Japanese continued to push the Chinese forces back,

capturing the capital Nanking in December 1937. After the fall of Nanking, tens

of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians and disarmed

combatants were murdered by the Japanese.

In March 1938, Nationalist Chinese forces won their first

major victory at Taierzhuang but then the city of Xuzhou was taken by Japanese

in May. In June 1938, Chinese forces stalled the Japanese advance by flooding

the Yellow River; this maneuver bought time for the Chinese to prepare their

defenses at Wuhan, but the city was taken by October. Japanese military

victories did not bring about the collapse of Chinese resistance that Japan had

hoped to achieve; instead the Chinese government relocated inland to Chongqing

and continued the war.

Soviet-Japanese Border Conflicts

Japanese forces in Manchukuo had sporadic border clashes

with the Soviet Union and Mongolia. The Japanese doctrine of Hokushin-ron,

which emphasized Japan's expansion northward, was favored by the Imperial Army

during this time. With the devastating Japanese defeat at Khalkin Gol in 1939

and ally Nazi Germany pursuing neutrality with the Soviets, this policy would

prove difficult to maintain. Japan and the Soviet Union eventually signed a

Neutrality Pact in April 1941, and Japan adopted the doctrine of Nanshin-ron,

which took its focus southward, eventually leading to its war with the United

States and the Western Allies.

European Occupations

and Agreements

In Europe, Germany and Italy were becoming more aggressive.

In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria, again provoking little response from

other European powers. Encouraged, Hitler began pressing German claims on the

Sudetenland, an area of Czechoslovakia with a predominantly ethnic German

population; and soon Britain and France followed the counsel of British Prime

Minister Neville Chamberlain and conceded this territory to Germany in the

Munich Agreement, which was made against the wishes of the Czechoslovak

government, in exchange for a promise of no further territorial demands. Soon

afterwards, Germany and Italy forced Czechoslovakia to cede additional

territory to Hungary and Poland.

Although all of Germany's stated demands had been satisfied

by the agreement, privately Hitler was furious that British interference had

prevented him from seizing all of Czechoslovakia in one operation. In

subsequent speeches Hitler attacked British and Jewish "war-mongers"

and in January 1939 secretly ordered a major build-up of the German navy to

challenge British naval supremacy. In March 1939, Germany invaded the remainder

of Czechoslovakia and subsequently split it into the German Protectorate of

Bohemia and Moravia and a pro-German client state, the Slovak Republic. Hitler

also delivered an ultimatum to Lithuania, forcing the concession of the

Klaipėda Region.

Greatly alarmed and with Hitler making further demands on

the Free City of Danzig, Britain and France guaranteed their support for Polish

independence; when Italy conquered Albania in April 1939, the same guarantee

was extended to Romania and Greece. Shortly after the Franco-British pledge to

Poland, Germany and Italy formalized their own alliance with the Pact of Steel.

Hitler accused Britain and Poland of trying to "encircle" Germany and

renounced the Anglo-German Naval Agreement and the German–Polish Non-Aggression

Pact.

In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression treaty with a secret protocol. The

parties gave each other rights to "spheres of influence" (western

Poland and Lithuania for Germany; eastern Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia and

Bessarabia for the USSR). It also raised the question of continuing Polish

independence. The agreement was crucial to Hitler because it assured that

Germany would not have to face the prospect of a two-front war, as it had in

World War I, after it defeated Poland.

The situation reached a general crisis in late August as

German troops continued to mobilize against the Polish border. In a private

meeting with the Italian foreign minister, Count Ciano, Hitler asserted that

Poland was a "doubtful neutral" that needed to either yield to his demands

or be "liquidated" to prevent it from drawing off German troops in

the future "unavoidable" war with the Western democracies. He did not

believe Britain or France would intervene in the conflict. On 23 August Hitler

ordered the attack to proceed on 26 August, but upon hearing that Britain had

concluded a formal mutual assistance pact with Poland and that Italy would

maintain neutrality, he decided to delay it. In response to British demands for

direct negotiations, Germany demanded on 29 August that a Polish plenipotentiary

immediately travel to Berlin to negotiate the handover of Danzig and the Polish

Corridor to Germany as well as to agree to safeguard the German minority in

Poland. The Poles refused to comply with this request and on the night of 30–31

August in a violent interview with Neville Henderson, Ribbentrop declared that

Germany considered its proposals rejected.

Course of the War

War Breaks Out In Europe (1939–40)

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland under the false

pretext that the Poles had carried out a series of sabotage operations against

German targets. Two days later, on 3 September, after a British ultimatum to

Germany to cease military operations was ignored, France and the United

Kingdom, followed by the fully independent Dominions of the British

Commonwealth—Australia (3 September), Canada (10 September), New Zealand (3

September), and South Africa (6 September)—declared war on Germany. However,

initially the alliance provided limited direct military support to Poland,

consisting of a cautious, half-hearted French probe into the Saarland. The

Western Allies also began a naval blockade of Germany, which aimed to damage

the country's economy and war effort. Germany responded by ordering U-boat

warfare against Allied merchant and warships, which was to later escalate into

the Battle of the Atlantic.

On 17 September 1939, after signing a cease-fire with Japan,

the Soviets invaded Poland from the east. The Polish army was defeated and

Warsaw surrendered to the Germans on 27 September, with final pockets of

resistance surrendering on 6 October. Poland's territory was divided between

Germany and the Soviet Union, with Lithuania and Slovakia also receiving small

shares. After the defeat of Poland's armed forces, the Polish resistance

established an Underground State and a partisan Home Army. About 100,000 Polish

military personnel were evacuated to Romania and the Baltic countries; many of

these soldiers later fought against the Germans in other theatres of the war.

Poland's Enigma codebreakers were also evacuated to France.

On 6 October Hitler made a public peace overture to the

United Kingdom and France, but said that the future of Poland was to be

determined exclusively by Germany and the Soviet Union. Chamberlain rejected

this on 12 October, saying "Past experience has shown that no reliance can

be placed upon the promises of the present German Government." After this

rejection Hitler ordered an immediate offensive against France, but bad weather

forced repeated postponements until the spring of 1940.

After signing the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship,

Cooperation and Demarcation, the Soviet Union forced the Baltic

countries—Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—to allow it to station Soviet troops in

their countries under pacts of "mutual assistance." Finland rejected

territorial demands, prompting a Soviet invasion in November 1939. The

resulting Winter War ended in March 1940 with Finnish concessions. The United

Kingdom and France, treating the Soviet attack on Finland as tantamount to its

entering the war on the side of the Germans, responded to the Soviet invasion

by supporting the USSR's expulsion from the League of Nations.

In June 1940, the Soviet Union forcibly annexed Estonia,

Latvia and Lithuania, and the disputed Romanian regions of Bessarabia, Northern

Bukovina and Hertza. Meanwhile, Nazi-Soviet political rapprochement and

economic co-operation gradually stalled, and both states began preparations for

war.

Western Europe (1940–41)

In April 1940, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway to protect

shipments of iron ore from Sweden, which the Allies were attempting to cut off

by unilaterally mining neutral Norwegian waters. Denmark capitulated after a

few hours, and despite Allied support, during which the important harbor of

Narvik temporarily was recaptured from the Germans, Norway was conquered within

two months. British discontent over the Norwegian campaign led to the

replacement of the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, with Winston

Churchill on 10 May 1940.

Germany launched an offensive against France and, adhering

to the Manstein Plan also attacked the neutral nations of Belgium, the

Netherlands, and Luxembourg on 10 May 1940. That same day British forces landed

in Iceland and the Faroes to preempt a possible German invasion of the islands.

The U.S. in close co-operation with the Danish envoy to Washington D.C., agreed

to protect Greenland, laying the political framework for the formal

establishment of bases in April 1941. The Netherlands and Belgium were overrun

using blitzkrieg tactics in a few days and weeks, respectively. The

French-fortified Maginot Line and the main body the Allied forces which had

moved into Belgium were circumvented by a flanking movement through the thickly

wooded Ardennes region, mistakenly perceived by Allied planners as an

impenetrable natural barrier against armored vehicles. As a result, the bulk of

the Allied armies found themselves trapped in an encirclement and were beaten.

The majority were taken prisoner, whilst over 300,000, mostly British and

French, were evacuated from the continent at Dunkirk by early June, although

abandoning almost all of their equipment.

On 10 June, Italy invaded France, declaring war on both

France and the United Kingdom. Paris fell to the Germans on 14 June and eight

days later France signed an armistice with Germany and was soon divided into

German and Italian occupation zones, and an unoccupied rump state under the

Vichy Regime, which, though officially neutral, was generally aligned with

Germany. France kept its fleet but the British feared the Germans would seize

it, so on 3 July, the British attacked it.

The Battle of Britain began in early July with Luftwaffe

attacks on shipping and harbors. On 19 July, Hitler again publicly offered to

end the war, saying he had no desire to destroy the British Empire. The United

Kingdom rejected this ultimatum. The main German air superiority campaign

started in August but failed to defeat RAF Fighter Command, and a proposed

invasion was postponed indefinitely on 17 September. The German strategic

bombing offensive intensified as night attacks on London and other cities in

the Blitz, but largely failed to disrupt the British war effort.

Using newly captured French ports, the German Navy enjoyed

success against an over-extended Royal Navy, using U-boats against British

shipping in the Atlantic. The British scored a significant victory on 27 May

1941 by sinking the German battleship Bismarck. Perhaps most importantly,

during the Battle of Britain the Royal Air Force had successfully resisted the

Luftwaffe's assault, and the German bombing campaign largely ended in May 1941.

Throughout this period, the neutral United States took

measures to assist China and the Western Allies. In November 1939, the American

Neutrality Act was amended to allow "cash and carry" purchases by the

Allies. In 1940, following the German capture of Paris, the size of the United

States Navy was significantly increased. In September, the United States

further agreed to a trade of American destroyers for British bases. Still, a

large majority of the American public continued to oppose any direct military

intervention into the conflict well into 1941.

Although Roosevelt had promised to keep the United States

out of the war, he nevertheless took concrete steps to prepare for war. In

December 1940 he accused Hitler of planning world conquest and ruled out

negotiations as useless, calling for the U.S. to become an "arsenal for

democracy" and promoted the passage of Lend-Lease aid to support the

British war effort. In January 1941 secret high level staff talks with the

British began for the purposes of determining how to defeat Germany should the

U.S. enter the war. They decided on a number of offensive policies, including

an air offensive, the "early elimination" of Italy, raids, support of

resistance groups, and the capture of positions to launch an offensive against

Germany.

At the end of September 1940, the Tripartite Pact united

Japan, Italy and Germany to formalize the Axis Powers. The Tripartite Pact

stipulated that any country, with the exception of the Soviet Union, not in the

war which attacked any Axis Power would be forced to go to war against all

three. The Axis expanded in November 1940 when Hungary, Slovakia and Romania

joined the Tripartite Pact. Romania would make a major contribution (as did

Hungary) to the Axis war against the USSR, partially to recapture territory

ceded to the USSR, partially to pursue its leader Ion Antonescu's desire to

combat communism.

Mediterranean (1940–41)

Italy began operations in the Mediterranean, initiating a

siege of Malta in June, conquering British Somaliland in August, and making an

incursion into British-held Egypt in September 1940. In October 1940, Italy

started the Greco-Italian War because of Mussolini's jealousy of Hitler's success

but within days was repulsed and pushed back into Albania, where a stalemate

soon occurred. The United Kingdom responded to Greek requests for assistance by

sending troops to Crete and providing air support to Greece. Hitler decided

that when the weather improved he would take action against Greece to assist

the Italians and prevent the British from gaining a foothold in the Balkans, to

strike against the British naval dominance of the Mediterranean, and to secure

his hold on Romanian oil.

In December 1940, British Commonwealth forces began

counter-offensives against Italian forces in Egypt and Italian East Africa. The

offensive in North Africa was highly successful and by early February 1941

Italy had lost control of eastern Libya and large numbers of Italian troops had

been taken prisoner. The Italian Navy also suffered significant defeats, with

the Royal Navy putting three Italian battleships out of commission by a carrier

attack at Taranto, and neutralizing several more warships at the Battle of Cape

Matapan.

The Germans soon intervened to assist Italy. Hitler sent

German forces to Libya in February, and by the end of March they had launched

an offensive which drove back the Commonwealth forces which had been weakened

to support Greece. In under a month, Commonwealth forces were pushed back into

Egypt with the exception of the besieged port of Tobruk. The Commonwealth

attempted to dislodge Axis forces in May and again in June, but failed on both

occasions.

By late March 1941, following Bulgaria's signing of the

Tripartite Pact, the Germans were in position to intervene in Greece. Plans

were changed, however, because of developments in neighboring Yugoslavia. The

Yugoslav government had signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 March, only to be

overthrown two days later by a British-encouraged coup. Hitler viewed the new

regime as hostile and immediately decided to eliminate it. On 6 April Germany

simultaneously invaded both Yugoslavia and Greece, making rapid progress and

forcing both nations to surrender within the month. The British were driven

from the Balkans after Germany conquered the Greek island of Crete by the end

of May. Although the Axis victory was swift, bitter partisan warfare

subsequently broke out against the Axis occupation of Yugoslavia, which continued

until the end of the war.

The Allies did have some successes during this time. In the

Middle East, Commonwealth forces first quashed an uprising in Iraq which had

been supported by German aircraft from bases within Vichy-controlled Syria,

then, with the assistance of the Free French, invaded Syria and Lebanon to

prevent further such occurrences.

Axis Attack On the USSR (1941)

With the situation in Europe and Asia relatively stable,

Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union made preparations. With the Soviets wary

of mounting tensions with Germany and the Japanese planning to take advantage

of the European War by seizing resource-rich European possessions in Southeast

Asia, the two powers signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact in April 1941.

By contrast, the Germans were steadily making preparations for an attack on the

Soviet Union, massing forces on the Soviet border.

Hitler believed that Britain's refusal to end the war was

based on the hope that the United States and the Soviet Union would enter the war

against Germany sooner or later. He therefore decided to try to strengthen

Germany's relations with the Soviets, or failing that, to attack and eliminate

them as a factor. In November 1940, negotiations took place to determine if the

Soviet Union would join the Tripartite Pact. The Soviets showed some interest,

but asked for concessions from Finland, Bulgaria, Turkey, and Japan that

Germany considered unacceptable. On 18 December 1940, Hitler issued the

directive to prepare for an invasion of the Soviet Union.

On 22 June 1941, Germany, supported by Italy and Romania,

invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, with Germany accusing the

Soviets of plotting against them. They were joined shortly by Finland and

Hungary. The primary targets of this surprise offensive were the Baltic region,

Moscow and Ukraine, with the ultimate goal of ending the 1941 campaign near the

Arkhangelsk-Astrakhan line, from the Caspian to the White Seas. Hitler's

objectives were to eliminate the Soviet Union as a military power, exterminate

Communism, generate Lebensraum ("living space") by dispossessing the

native population and guarantee access to the strategic resources needed to

defeat Germany's remaining rivals.

Although the Red Army was preparing for strategic counter-offensives

before the war, Barbarossa forced the Soviet supreme command to adopt a

strategic defense. During the summer, the Axis made significant gains into

Soviet territory, inflicting immense losses in both personnel and materiel. By

the middle of August, however, the German Army High Command decided to suspend

the offensive of a considerably depleted Army Group Centre, and to divert the

2nd Panzer Group to reinforce troops advancing towards central Ukraine and

Leningrad. The Kiev offensive was overwhelmingly successful, resulting in

encirclement and elimination of four Soviet armies, and made further advance

into Crimea and industrially developed Eastern Ukraine (the First Battle of

Kharkov) possible.

The diversion of three quarters of the Axis troops and the

majority of their air forces from France and the central Mediterranean to the

Eastern Front prompted Britain to reconsider its grand strategy. In July, the

UK and the Soviet Union formed a military alliance against Germany The British

and Soviets invaded Iran to secure the Persian Corridor and Iran's oil fields.

In August, the United Kingdom and the United States jointly issued the Atlantic

Charter.

By October Axis operational objectives in Ukraine and the

Baltic region were achieved, with only the sieges of Leningrad and Sevastopol

continuing. A major offensive against Moscow was renewed; after two months of

fierce battles in increasingly harsh weather the German army almost reached the

outer suburbs of Moscow, where the exhausted troops were forced to suspend

their offensive. Large territorial gains were made by Axis forces, but their

campaign had failed to achieve its main objectives: two key cities remained in

Soviet hands, the Soviet capability to resist was not broken, and the Soviet

Union retained a considerable part of its military potential. The blitzkrieg

phase of the war in Europe had ended.

By early December, freshly mobilized reserves allowed the

Soviets to achieve numerical parity with Axis troops. This, as well as

intelligence data which established that a minimal number of Soviet troops in

the East would be sufficient to deter any attack by the Japanese Kwantung Army,

allowed the Soviets to begin a massive counter-offensive that started on 5

December all along the front and pushed German troops 100–250 kilometers

(62–155 mi) west.

War Breaks Out In the Pacific (1941)

In 1939 the United States had renounced its trade treaty

with Japan and beginning with an aviation gasoline ban in July 1940 Japan had

become subject to increasing economic pressure. During this time, Japan

launched its first attack against Changsha, a strategically important Chinese

city, but was repulsed by late September. Despite several offensives by both

sides, the war between China and Japan was stalemated by 1940. To increase

pressure on China by blocking supply routes, and to better position Japanese

forces in the event of a war with the Western powers, Japan invaded and

occupied northern Indochina. Afterwards, the United States embargoed iron,

steel and mechanical parts against Japan. Other sanctions soon followed.

In August of that year, Chinese communists launched an

offensive in Central China; in retaliation, Japan instituted harsh measures in

occupied areas to reduce human and material resources for the communists. Continued

antipathy between Chinese communist and nationalist forces culminated in armed

clashes in January 1941, effectively ending their co-operation. In March, the

Japanese 11th army attacked the headquarters of the Chinese 19th army but was

repulsed during Battle of Shanggao. In September, Japan attempted to take the

city of Changsha again and clashed with Chinese nationalist forces.

German successes in Europe encouraged Japan to increase

pressure on European governments in Southeast Asia. The Dutch government agreed

to provide Japan some oil supplies from the Dutch East Indies, but negotiations

for additional access to their resources ended in failure in June 1941. In July

1941 Japan sent troops to southern Indochina, thus threatening British and

Dutch possessions in the Far East. The United States, United Kingdom and other

Western governments reacted to this move with a freeze on Japanese assets and a

total oil embargo.

Since early 1941 the United States and Japan had been

engaged in negotiations in an attempt to improve their strained relations and

end the war in China. During these negotiations Japan advanced a number of

proposals which were dismissed by the Americans as inadequate. At the same time

the U.S., Britain, and the Netherlands engaged in secret discussions for the

joint defense of their territories, in the event of a Japanese attack against

any of them. Roosevelt reinforced the Philippines (an American protectorate

scheduled for independence in 1946) and warned Japan that the U.S. would react to

Japanese attacks against any "neighboring countries."

Frustrated at the lack of progress and feeling the pinch of

the American-British-Dutch sanctions, Japan prepared for war. On 20 November it

presented an interim proposal as its final offer. It called for the end of

American aid to China and to supply oil and other resources to Japan. In

exchange they promised not to launch any attacks in Southeast Asia and to

withdraw their forces from their threatening positions in southern Indochina.

The American counter-proposal of 26 November required that Japan evacuate all

of China without conditions and conclude non-aggression pacts with all Pacific

powers. That meant Japan was essentially forced to choose between abandoning

its ambitions in China, or seizing the natural resources it needed in the Dutch

East Indies by force; the Japanese military did not consider the former an

option, and many officers considered the oil embargo an unspoken declaration of

war.

Japan planned to rapidly seize European colonies in Asia to

create a large defensive perimeter stretching into the Central Pacific; the

Japanese would then be free to exploit the resources of Southeast Asia while

exhausting the over-stretched Allies by fighting a defensive war. To prevent

American intervention while securing the perimeter it was further planned to

neutralize the United States Pacific Fleet and the American military presence

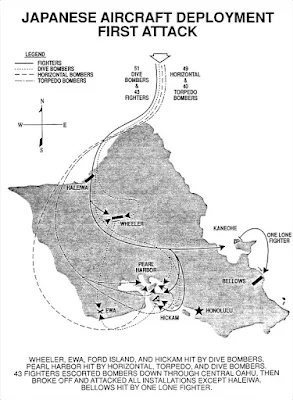

in the Philippines from the outset. On 7 December 1941 (8 December in Asian

time zones), Japan attacked British and American holdings with

near-simultaneous offensives against Southeast Asia and the Central Pacific.

These included an attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, the

Philippines, landings in Thailand and Malaya and the battle of Hong Kong.

These attacks led the United States, Britain, China,

Australia and several other states to formally declare war on Japan, whereas

the Soviet Union, being heavily involved in large-scale hostilities with

European Axis countries, maintained its neutrality agreement with Japan.

Germany, followed by the other Axis states, declared war on the United States

in solidarity with Japan, citing as justification the American attacks on

German war vessels that had been ordered by Roosevelt.

Axis Advance Stalls (1942–43)

In January 1942, the Big Four (the United States, Britain,

Soviet Union, China) and 22 smaller or exiled governments issued the

Declaration by United Nations, thereby affirming the Atlantic Charter, and

agreeing to not to sign a separate peace with the Axis powers.

During 1942, Allied officials debated on the appropriate

grand strategy to pursue. All agreed that defeating Germany was the primary

objective. The Americans favored a straightforward, large-scale attack on

Germany through France. The Soviets were also demanding a second front. The

British, on the other hand, argued that military operations should target

peripheral areas to wear out German strength, lead to increasing

demoralization, and bolster resistance forces. Germany itself would be subject

to a heavy bombing campaign. An offensive against Germany would then be

launched primarily by Allied armor without using large-scale armies.

Eventually, the British persuaded the Americans that a landing in France was

infeasible in 1942 and they should instead focus on driving the Axis out of

North Africa.

At the Casablanca Conference in early 1943, the Allies

reiterated the statements issued in the 1942 Declaration by the United Nations,

and demanded the unconditional surrender of their enemies. The British and

Americans agreed to continue to press the initiative in the Mediterranean by

invading Sicily to fully secure the Mediterranean supply routes. Although the

British argued for further operations in the Balkans to bring Turkey into the

war, in May 1943, the Americans extracted a British commitment to limit Allied

operations in the Mediterranean to an invasion of the Italian mainland and to

invade France in 1944.

Pacific (1942–43)

By the end of April 1942, Japan and its ally Thailand had

almost fully conquered Burma, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, and

Rabaul, inflicting severe losses on Allied troops and taking a large number of

prisoners. Despite stubborn resistance by Filipino and U.S. forces, the

Philippine Commonwealth was eventually captured in May 1942, forcing its

government into exile. On 16 April, in Burma, 7,000 British soldiers were

encircled by the Japanese 33rd Division during the Battle of Yenangyaung and

rescued by the Chinese 38th Division. Japanese forces also achieved naval

victories in the South China Sea, Java Sea and Indian Ocean, and bombed the

Allied naval base at Darwin, Australia. In January 1942, the only Allied

success against Japan was a Chinese victory at Changsha. These easy victories

over unprepared U.S. and European opponents left Japan overconfident, as well

as overextended.

In early May 1942, Japan initiated operations to capture

Port Moresby by amphibious assault and thus sever communications and supply

lines between the United States and Australia. The planned invasion was thwarted

when an Allied task force centered on two American fleet carriers fought

Japanese naval forces to a draw in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Japan's next

plan, motivated by the earlier Doolittle Raid, was to seize Midway Atoll and

lure American carriers into battle to be eliminated; as a diversion, Japan

would also send forces to occupy the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. In early June,

Japan put its operations into action but the Americans, having broken Japanese

naval codes in late May, were fully aware of the plans and force dispositions

and used this knowledge to achieve a decisive victory at Midway over the

Imperial Japanese Navy.

With its capacity for aggressive action greatly diminished

as a result of the Midway battle, Japan chose to focus on a belated attempt to

capture Port Moresby by an overland campaign in the Territory of Papua. The

Americans planned a counter-attack against Japanese positions in the southern

Solomon Islands, primarily Guadalcanal, as a first step towards capturing

Rabaul, the main Japanese base in Southeast Asia.

Both plans started in July, but by mid-September, the Battle

for Guadalcanal took priority for the Japanese, and troops in New Guinea were

ordered to withdraw from the Port Moresby area to the northern part of the

island, where they faced Australian and United States troops in the Battle of

Buna-Gona. Guadalcanal soon became a focal point for both sides with heavy

commitments of troops and ships in the battle for Guadalcanal. By the start of

1943, the Japanese were defeated on the island and withdrew their troops. In

Burma, Commonwealth forces mounted two operations. The first, an offensive into

the Arakan region in late 1942, went disastrously, forcing a retreat back to

India by May 1943. The second was the insertion of irregular forces behind

Japanese front-lines in February which, by the end of April, had achieved mixed

results.

Eastern Front (1942–43)

Despite considerable losses, in early 1942 Germany and its

allies stopped a major Soviet offensive in central and southern Russia, keeping

most territorial gains they had achieved during the previous year. In May the

Germans defeated Soviet offensives in the Kerch Peninsula and at Kharkiv, and

then launched their main summer offensive against southern Russia in June 1942,

to seize the oil fields of the Caucasus and occupy Kuban steppe, while

maintaining positions on the northern and central areas of the front. The

Germans split Army Group South into two groups: Army Group A advanced to the

lower Don River and struck south-east to the Caucasus, while Army Group B

headed towards the Volga River. The Soviets decided to make their stand at

Stalingrad on the Volga.

By mid-November, the Germans had nearly taken Stalingrad in

bitter street fighting when the Soviets began their second winter

counter-offensive, starting with an encirclement of German forces at Stalingrad

and an assault on the Rzhev salient near Moscow, though the latter failed

disastrously. By early February 1943, the German Army had taken tremendous

losses; German troops at Stalingrad had been forced to surrender, and the

front-line had been pushed back beyond its position before the summer

offensive. In mid-February, after the Soviet push had tapered off, the Germans

launched another attack on Kharkov, creating a salient in their front line

around the Russian city of Kursk.

Western Europe/Atlantic and Mediterranean (1942–43)

Exploiting poor American naval command decisions, the German

navy ravaged Allied shipping off the American Atlantic coast. By November 1941,

Commonwealth forces had launched a counter-offensive, Operation Crusader, in

North Africa, and reclaimed all the gains the Germans and Italians had made. In

North Africa, the Germans launched an offensive in January, pushing the British

back to positions at the Gazala Line by early February, followed by a temporary

lull in combat which Germany used to prepare for their upcoming offensives.

Concerns the Japanese might use bases in Vichy-held Madagascar caused the

British to invade the island in early May 1942. An Axis offensive in Libya

forced an Allied retreat deep inside Egypt until Axis forces were stopped at El

Alamein. On the Continent, raids of Allied commandos on strategic targets,

culminating in the disastrous Dieppe Raid, demonstrated the Western Allies'

inability to launch an invasion of continental Europe without much better

preparation, equipment, and operational security.

In August 1942, the Allies succeeded in repelling a second

attack against El Alamein and, at a high cost, managed to deliver desperately needed

supplies to the besieged Malta. A few months later, the Allies commenced an

attack of their own in Egypt, dislodging the Axis forces and beginning a drive

west across Libya. This attack was followed up shortly after by Anglo-American

landings in French North Africa, which resulted in the region joining the

Allies. Hitler responded to the French colony's defection by ordering the

occupation of Vichy France; although Vichy forces did not resist this violation

of the armistice, they managed to scuttle their fleet to prevent its capture by

German forces. The now pincered Axis forces in Africa withdrew into Tunisia,

which was conquered by the Allies in May 1943.

In early 1943 the British and Americans began the Combined

Bomber Offensive, a strategic bombing campaign against Germany. The goals were

to disrupt the German war economy, reduce German morale, and

"de-house" the civilian population.

Allies Gain Momentum (1943–44)

After the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Allies initiated several

operations against Japan in the Pacific. In May 1943, Canadian and U.S. forces

were sent to eliminate Japanese forces from the Aleutians. Soon after, the U.S.

with support from Australian and New Zealand forces began major operations to

isolate Rabaul by capturing surrounding islands, and to breach the Japanese

Central Pacific perimeter at the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. By the end of

March 1944, the Allies had completed both of these objectives, and additionally

neutralized the major Japanese base at Truk in the Caroline Islands. In April,

the Allies launched an operation to retake Western New Guinea.

In the Soviet Union, both the Germans and the Soviets spent

the spring and early summer of 1943 preparing for large offensives in central

Russia. On 4 July 1943, Germany attacked Soviet forces around the Kursk Bulge.

Within a week, German forces had exhausted themselves against the Soviets'

deeply echeloned and well-constructed defenses and, for the first time in the

war, Hitler cancelled the operation before it had achieved tactical or

operational success. This decision was partially affected by the Western

Allies' invasion of Sicily launched on 9 July which, combined with previous

Italian failures, resulted in the ousting and arrest of Mussolini later that

month. Also, in July 1943 the British firebombed Hamburg killing over 40,000

people.

On 12 July 1943, the Soviets launched their own

counter-offensives, thereby dispelling any chance of German victory or even

stalemate in the east. The Soviet victory at Kursk marked the end of German

superiority, giving the Soviet Union the initiative on the Eastern Front. The

Germans tried to stabilize their eastern front along the hastily fortified

Panther-Wotan line, but the Soviets broke through it at Smolensk and by the

Lower Dnieper Offensives.

On 3 September 1943, the Western Allies invaded the Italian

mainland, following Italy's armistice with the Allies. Germany responded by

disarming Italian forces, seizing military control of Italian areas, and

creating a series of defensive lines. German special forces then rescued

Mussolini, who then soon established a new client state in German occupied

Italy named the Italian Social Republic, causing an Italian civil war. The

Western Allies fought through several lines until reaching the main German defensive

line in mid-November.

German operations in the Atlantic also suffered. By May

1943, as Allied counter-measures became increasingly effective, the resulting

sizeable German submarine losses forced a temporary halt of the German Atlantic

naval campaign. In November 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill

met with Chiang Kai-shek in Cairo and then with Joseph Stalin in Tehran. The

former conference determined the post-war return of Japanese territory, while

the latter included agreement that the Western Allies would invade Europe in

1944 and that the Soviet Union would declare war on Japan within three months

of Germany's defeat.

From November 1943, during the seven-week Battle of Changde,

the Chinese forced Japan to fight a costly war of attrition, while awaiting

Allied relief. In January 1944, the Allies launched a series of attacks in

Italy against the line at Monte Cassino and tried to outflank it with landings

at Anzio. By the end of January, a major Soviet offensive expelled German forces

from the Leningrad region, ending the longest and most lethal siege in history.

The following Soviet offensive was halted on the pre-war

Estonian border by the German Army Group North aided by Estonians hoping to

re-establish national independence. This delay slowed subsequent Soviet

operations in the Baltic Sea region. By late May 1944, the Soviets had

liberated Crimea, largely expelled Axis forces from Ukraine, and made

incursions into Romania, which were repulsed by the Axis troops. The Allied

offensives in Italy had succeeded and, at the expense of allowing several

German divisions to retreat, on 4 June, Rome was captured.

The Allies had mixed success in mainland Asia. In March

1944, the Japanese launched the first of two invasions, an operation against British

positions in Assam, India, and soon besieged Commonwealth positions at Imphal

and Kohima. In May 1944, British forces mounted a counter-offensive that drove

Japanese troops back to Burma, and Chinese forces that had invaded northern

Burma in late 1943 besieged Japanese troops in Myitkyina. The second Japanese

invasion of China aimed to destroy China's main fighting forces, secure

railways between Japanese-held territory and capture Allied airfields. By June,

the Japanese had conquered the province of Henan and begun a new attack on

Changsha in the Hunan province.

Allies Close In (1944)

On 6 June 1944 (known as D-Day), after three years of Soviet

pressure, the Western Allies invaded northern France. After reassigning several

Allied divisions from Italy, they also attacked southern France. These landings

were successful, and led to the defeat of the German Army units in France.

Paris was liberated by the local resistance assisted by the Free French Forces,

both led by General Charles de Gaulle, on 25 August and the Western Allies

continued to push back German forces in western Europe during the latter part

of the year. An attempt to advance into northern Germany spearheaded by a major

airborne operation in the Netherlands failed. After that, the Western Allies

slowly pushed into Germany, but failed to cross the Rur river in a large

offensive. In Italy, Allied advance also slowed due to the last major German

defensive line.

On 22 June, the Soviets launched a strategic offensive in

Belarus ("Operation Bagration") that destroyed the German Army Group

Centre almost completely. Soon after that another Soviet strategic offensive

forced German troops from Western Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The Soviet

advance prompted resistance forces in Poland to initiate several uprisings

against the German occupation. However, the largest of these in Warsaw where

German soldiers massacred 200,000 civilians and a national uprising in Slovakia

did not receive Soviet support and were subsequently suppressed by the Germans.

The Red Army's strategic offensive in eastern Romania cut off and destroyed the

considerable German troops there and triggered a successful coup d'état in

Romania and in Bulgaria, followed by those countries' shift to the Allied side.

In September 1944, Soviet troops advanced into Yugoslavia

and forced the rapid withdrawal of German Army Groups E and F in Greece,

Albania and Yugoslavia to rescue them from being cut off. By this point, the

Communist-led Partisans under Marshal Josip Broz Tito, who had led an increasingly

successful guerrilla campaign against the occupation since 1941, controlled

much of the territory of Yugoslavia and engaged in delaying efforts against

German forces further south. In northern Serbia, the Red Army, with limited

support from Bulgarian forces, assisted the Partisans in a joint liberation of

the capital city of Belgrade on 20 October. A few days later, the Soviets

launched a massive assault against German-occupied Hungary that lasted until

the fall of Budapest in February 1945. Unlike impressive Soviet victories in

the Balkans, bitter Finnish resistance to the Soviet offensive in the Karelian

Isthmus denied the Soviets occupation of Finland and led to a Soviet-Finnish

armistice on relatively mild conditions, although Finland later shifted to the

Allied side.

By the start of July 1944, Commonwealth forces in Southeast

Asia had repelled the Japanese sieges in Assam, pushing the Japanese back to

the Chindwin River while the Chinese captured Myitkyina. In China, the Japanese

had more successes, having finally captured Changsha in mid-June and the city

of Hengyang by early August. Soon after, they invaded the province of Guangxi,

winning major engagements against Chinese forces at Guilin and Liuzhou by the

end of November and successfully linking up their forces in China and Indochina

by mid-December.

In the Pacific, U.S. forces continued to press back the

Japanese perimeter. In mid-June 1944, they began their offensive against the

Mariana and Palau islands, and decisively defeated Japanese forces in the

Battle of the Philippine Sea. These defeats led to the resignation of the

Japanese Prime Minister, Hideki Tojo, and provided the United States with air

bases to launch intensive heavy bomber attacks on the Japanese home islands. In

late October, American forces invaded the Filipino island of Leyte; soon after,

Allied naval forces scored another large victory in the Battle of Leyte Gulf,

one of the largest naval battles in history.

Axis Collapse, Allied Victory (1944–45)

On 16 December 1944, Germany made a last attempt on the

Western Front by using most of its remaining reserves to launch a massive

counter-offensive in the Ardennes to split the Western Allies, encircle large

portions of Western Allied troops and capture their primary supply port at

Antwerp to prompt a political settlement. By January, the offensive had been

repulsed with no strategic objectives fulfilled. In Italy, the Western Allies

remained stalemated at the German defensive line. In mid-January 1945, the

Soviets and Poles attacked in Poland, pushing from the Vistula to the Oder

river in Germany, and overran East Prussia. On 4 February, U.S., British, and

Soviet leaders met for the Yalta Conference. They agreed on the occupation of

post-war Germany, and on when the Soviet Union would join the war against

Japan.

In February, the Soviets entered Silesia and Pomerania,

while Western Allies entered western Germany and closed to the Rhine river. By

March, the Western Allies crossed the Rhine north and south of the Ruhr,

encircling the German Army Group B, while the Soviets advanced to Vienna. In

early April, the Western Allies finally pushed forward in Italy and swept

across western Germany, while Soviet and Polish forces stormed Berlin in late

April. American and Soviet forces joined on Elbe river on 25 April. On 30 April

1945, the Reichstag was captured, signaling the military defeat of Nazi

Germany.

Several changes in leadership occurred during this period.

On 12 April, President Roosevelt died and was succeeded by Harry Truman. Benito

Mussolini was killed by Italian partisans on 28 April. Two days later, Hitler

committed suicide, and was succeeded by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz.

German forces surrendered in Italy on 29 April. Total and

unconditional surrender was signed on 7 May, to be effective by the end of 8

May. German Army Group Centre resisted in Prague until 11 May.

In the Pacific theatre, American forces accompanied by the

forces of the Philippine Commonwealth advanced in the Philippines, clearing

Leyte by the end of April 1945. They landed on Luzon in January 1945 and

recaptured Manila in March following a battle which reduced the city to ruins.

Fighting continued on Luzon, Mindanao, and other islands of the Philippines

until the end of the war. On the night of 9–10 March, B-29 bombers of the U.S.

Army Air Forces struck Tokyo with incendiary bombs, which killed 100,000 people

within a few hours. Over the next five months, American bombers firebombed 66

other Japanese cities, causing the destruction of untold numbers of buildings and

the deaths of between 350,000–500,000 Japanese civilians.

In May 1945, Australian troops landed in Borneo,

over-running the oilfields there. British, American, and Chinese forces

defeated the Japanese in northern Burma in March, and the British pushed on to

reach Rangoon by 3 May. Chinese forces started to counterattack in Battle of

West Hunan that occurred between 6 April and 7 June 1945. American naval and

amphibious forces also moved towards Japan, taking Iwo Jima by March, and

Okinawa by the end of June. At the same time American bombers were destroying

Japanese cities, American submarines cut off Japanese imports, drastically

reducing Japan's ability to supply its overseas forces.

On 11 July, Allied leaders met in Potsdam, Germany. They

confirmed earlier agreements about Germany, and reiterated the demand for

unconditional surrender of all Japanese forces by Japan, specifically stating

that "the alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction."

During this conference, the United Kingdom held its general election, and

Clement Attlee replaced Churchill as Prime Minister.

The Allies called for unconditional Japanese surrender in

the Potsdam declaration of 27 July, but the Japanese government was internally

divided on whether to make peace and did not respond. In early August, the

United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. Like the Japanese cities previously bombed by American airmen, the

U.S. and its allies justified the atomic bombings as military necessity to

avoid invading the Japanese home islands which would cost the lives of between

250,000–500,000 Allied troops and millions of Japanese troops and civilians.

Between the two bombings, the Soviets, pursuant to the Yalta agreement, invaded

Japanese-held Manchuria, and quickly defeated the Kwantung Army, which was the

largest Japanese fighting force. The Red Army also captured Sakhalin Island and

the Kuril Islands. On 15 August 1945, Japan surrendered, with the surrender

documents finally signed aboard the deck of the American battleship USS

Missouri on 2 September 1945, ending the war.

Aftermath

The Allies established occupation administrations in Austria

and Germany. The former became a neutral state, non-aligned with any political

bloc. The latter was divided into western and eastern occupation zones

controlled by the Western Allies and the USSR, accordingly. A denazification

program in Germany led to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals and the removal

of ex-Nazis from power, although this policy moved towards amnesty and

re-integration of ex-Nazis into West German society.

Germany lost a quarter of its pre-war (1937) territory.

Among the eastern territories, Silesia, Neumark and most of Pomerania were

taken over by Poland, East Prussia was divided between Poland and the USSR,

followed by the expulsion of the 9 million Germans from these provinces, as

well as the expulsion of 3 million Germans from the Sudetenland in

Czechoslovakia to Germany. By the 1950s, every fifth West German was a refugee

from the east. The Soviet Union also took over the Polish provinces east of the

Curzon line, from which 2 million Poles were expelled; north-east Romania,

parts of eastern Finland, and the three Baltic states were also incorporated

into the USSR.

In an effort to maintain peace, the Allies formed the United

Nations, which officially came into existence on 24 October 1945, and adopted

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, as a common standard for all

member nations. The great powers that were the victors of the war—the United

States, Soviet Union, China, Britain, and France—formed the permanent members

of the UN's Security Council. The five permanent members remain so to the

present, although there have been two seat changes, between the Republic of

China and the People's Republic of China in 1971, and between the Soviet Union

and its successor state, the Russian Federation, following the dissolution of

the Soviet Union. The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union

had begun to deteriorate even before the war was over.

Germany had been de facto divided, and two independent

states, the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic were

created within the borders of Allied and Soviet occupation zones, accordingly.

The rest of Europe was also divided into Western and Soviet spheres of

influence. Most eastern and central European countries fell into the Soviet

sphere, which led to establishment of Communist-led regimes, with full or

partial support of the Soviet occupation authorities. As a result, Poland,

Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Albania became Soviet

satellite states. Communist Yugoslavia conducted a fully independent policy,

causing tension with the USSR.

Post-war division of the world was formalized by two international

military alliances, the United States-led NATO and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact;

the long period of political tensions and military competition between them,

the Cold War, would be accompanied by an unprecedented arms race and proxy

wars.

In Asia, the United States led the occupation of Japan and

administrated Japan's former islands in the Western Pacific, while the Soviets

annexed Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. Korea, formerly under Japanese rule,

was divided and occupied by the U.S. in the South and the Soviet Union in the

North between 1945 and 1948. Separate republics emerged on both sides of the

38th parallel in 1948, each claiming to be the legitimate government for all of

Korea, which led ultimately to the Korean War.

In China, nationalist and communist forces resumed the civil

war in June 1946. Communist forces were victorious and established the People's

Republic of China on the mainland, while nationalist forces retreated to Taiwan

in 1949. In the Middle East, the Arab rejection of the United Nations Partition

Plan for Palestine and the creation of Israel marked the escalation of the

Arab-Israeli conflict. While European colonial powers attempted to retain some

or all of their colonial empires, their losses of prestige and resources during

the war rendered this unsuccessful, leading to decolonization.

The global economy suffered heavily from the war, although

participating nations were affected differently. The U.S. emerged much richer

than any other nation; it had a baby boom and by 1950 its gross domestic

product per person was much higher than that of any of the other powers and it

dominated the world economy. The UK and U.S. pursued a policy of industrial

disarmament in Western Germany in the years 1945–1948. Because of international

trade interdependencies this led to European economic stagnation and delayed

European recovery for several years.

Recovery began with the mid-1948 currency reform in Western

Germany, and was sped up by the liberalization of European economic policy that

the Marshall Plan (1948–1951) both directly and indirectly caused. The

post-1948 West German recovery has been called the German economic miracle.

Italy also experienced an economic boom and the French economy rebounded. By

contrast, the United Kingdom was in a state of economic ruin, and although it

received a quarter of the total Marshall Plan assistance, more than any other

European country, continued relative economic decline for decades.

The Soviet Union, despite enormous human and material

losses, also experienced rapid increase in production in the immediate post-war

era. Japan experienced incredibly rapid economic growth, becoming one of the

most powerful economies in the world by the 1980s. China returned to its

pre-war industrial production by 1952.

Impact

Casualties and War Crimes

Estimates for the total number of casualties in the war

vary, because many deaths went unrecorded. Most suggest that some 75 million

people died in the war, including about 20 million military personnel and 40

million civilians. Many of the civilians died because of deliberate genocide,

massacres, mass-bombings, disease, and starvation.

The Soviet Union lost around 27 million people during the

war, including 8.7 million military and 19 million civilian deaths. The largest

portion of military dead were 5.7 million ethnic Russians, followed by 1.3

million ethnic Ukrainians. A quarter of the people in the Soviet Union were

wounded or killed. Germany sustained 5.3 million military losses, mostly on the

Eastern Front and during the final battles in Germany.

Of the total number of deaths in World War II, approximately

85 percent—mostly Soviet and Chinese—were on the Allied side and 15 percent

were on the Axis side. Many of these deaths were caused by war crimes committed

by German and Japanese forces in occupied territories. An estimated 11 to 17

million civilians died either as a direct or as an indirect result of Nazi

ideological policies, including the systematic genocide of around 6 million

Jews during the Holocaust, along with a further 5 to 6 million ethnic Poles and

other Slavs (including Ukrainians and Belarusians)—Roma, homosexuals, and other

ethnic and minority groups. Hundreds of thousands (varying estimates) of ethnic

Serbs, along with gypsies and Jews, were murdered by the Axis-aligned Croatian

Ustaše in Yugoslavia, and retribution-related killings were committed just

after the war ended.

The best-known Japanese atrocity was the Nanking Massacre,

in which several hundred thousand Chinese civilians were raped and murdered. Between

3 million and more than 10 million civilians, mostly Chinese (estimated at 7.5

million), were killed by the Japanese occupation forces. Mitsuyoshi Himeta

reported that 2.7 million casualties occurred during the Sankō Sakusen. General

Yasuji Okamura implemented the policy in Heipei and Shantung.

Axis forces employed biological and chemical weapons. The

Imperial Japanese Army used a variety of such weapons during its invasion and

occupation of China (see Unit 731) and in early conflicts against the Soviets.

Both the Germans and Japanese tested such weapons against civilians and,

sometimes on prisoners of war.

The Soviet Union was responsible for the Katyn massacre of

22,000 Polish officers, and the imprisonment or execution of thousands of

political prisoners by the NKVD, in the Baltic states, and eastern Poland

annexed by the Red Army.

The mass-bombing of civilian areas, notably the cities of

Warsaw, Rotterdam and London; including the aerial targeting of hospitals and

fleeing refugees by the German Luftwaffe, along with the bombing of Tokyo, and

German cities of Dresden, Hamburg and Cologne by the Western Allies may be

considered as war crimes. The latter resulted in the destruction of more than

160 cities and the death of more than 600,000 German civilians. However, no

positive or specific customary international humanitarian law with respect to

aerial warfare existed before or during World War II.

Concentration Camps, Slave Labor, and Genocide

The German Government led by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party

was responsible for the Holocaust, the killing of approximately 6 million Jews,

as well as 2.7 million ethnic Poles, and 4 million others who were deemed

"unworthy of life" (including the disabled and mentally ill, Soviet

prisoners of war, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Romani) as

part of a program of deliberate extermination. About 12 million, most of whom

were Eastern Europeans, were employed in the German war economy as forced

laborers.

In addition to Nazi concentration camps, the Soviet gulags

(labor camps) led to the death of citizens of occupied countries such as

Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, as well as German prisoners of war

(POWs) and even Soviet citizens who had been or were thought to be supporters

of the Nazis. Sixty percent of Soviet POWs of the Germans died during the war.

Richard Overy gives the number of 5.7 million Soviet POWs. Of those, 57 percent

died or were killed, a total of 3.6 million. Soviet ex-POWs and repatriated

civilians were treated with great suspicion as potential Nazi collaborators,

and some of them were sent to the Gulag upon being checked by the NKVD.

Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, many of which were used as

labor camps, also had high death rates. The International Military Tribunal for

the Far East found the death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1 percent (for

American POWs, 37 percent), seven times that of POWs under the Germans and

Italians. While 37,583 prisoners from the UK, 28,500 from the Netherlands, and

14,473 from the United States were released after the surrender of Japan, the

number of Chinese released was only 56.

According to historian Zhifen Ju, at least five million

Chinese civilians from northern China and Manchukuo were enslaved between 1935

and 1941 by the East Asia Development Board, or Kōain, for work in mines and

war industries. After 1942, the number reached 10 million. The U.S. Library of

Congress estimates that in Java, between 4 and 10 million romusha ("manual

laborers"), were forced to work by the Japanese military. About 270,000 of

these Javanese laborers were sent to other Japanese-held areas in South East

Asia, and only 52,000 were repatriated to Java.

On 19 February 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066,

interning about 100,000 Japanese living on the West Coast. Canada had a similar

program. In addition, 14,000 German and Italian citizens who had been assessed

as being security risks were also interned.

In accordance with the Allied agreement made at the Yalta

Conference millions of POWs and civilians were used as forced labor by the

Soviet Union. In Hungary's case, Hungarians were forced to work for the Soviet

Union until 1955.

Occupation

In Europe, occupation came under two forms. In Western,

Northern and Central Europe (France, Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries, and

the annexed portions of Czechoslovakia) Germany established economic policies

through which it collected roughly 69.5 billion Reichmarks (27.8 billion U.S.

Dollars) by the end of the war, this figure does not include the sizeable

plunder of industrial products, military equipment, raw materials and other

goods. Thus, the income from occupied nations was over 40 percent of the income

Germany collected from taxation, a figure which increased to nearly 40 percent

of total German income as the war went on.

In the East, the much hoped for bounties of Lebensraum were

never attained as fluctuating front-lines and Soviet scorched earth policies

denied resources to the German invaders. Unlike in the West, the Nazi racial

policy encouraged excessive brutality against what it considered to be the

"inferior people" of Slavic descent; most German advances were thus

followed by mass executions. Although resistance groups formed in most occupied

territories, they did not significantly hamper German operations in either the

East or the West until late 1943.

In Asia, Japan termed nations under its occupation as being

part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, essentially a Japanese

hegemony which it claimed was for purposes of liberating colonized peoples. Although

Japanese forces were originally welcomed as liberators from European domination

in some territories, their excessive brutality turned local public opinion

against them within weeks. During Japan's initial conquest it captured

4,000,000 barrels (640,000 m3) of oil (~5.5×105 tons) left behind by retreating

Allied forces, and by 1943 was able to get production in the Dutch East Indies

up to 50 million barrels (~6.8×106 t), 76 percent of its 1940 output rate.

Home Fronts and Production

In Europe, before the outbreak of the war, the Allies had

significant advantages in both population and economics. In 1938, the Western

Allies (United Kingdom, France, Poland and British Dominions) had a 30 percent

larger population and a 30 percent higher gross domestic product than the

European Axis (Germany and Italy); if colonies are included, it then gives the

Allies more than a 5:1 advantage in population and nearly 2:1 advantage in GDP.

In Asia at the same time, China had roughly six times the population of Japan,

but only an 89 percent higher GDP; this is reduced to three times the

population and only a 38 percent higher GDP if Japanese colonies are included.

Though the Allies' economic and population advantages were

largely mitigated during the initial rapid blitzkrieg attacks of Germany and

Japan, they became the decisive factor by 1942, after the United States and

Soviet Union joined the Allies, as the war largely settled into one of

attrition. While the Allies' ability to out-produce the Axis is often

attributed to the Allies having more access to natural resources, other

factors, such as Germany and Japan's reluctance to employ women in the labor

force, Allied strategic bombing, and Germany's late shift to a war economy

contributed significantly. Additionally, neither Germany nor Japan planned to

fight a protracted war, and were not equipped to do so. To improve their

production, Germany and Japan used millions of slave laborers; Germany used

about 12 million people, mostly from Eastern Europe, while Japan used more than

18 million people in Far East Asia.

Advances in Technology and Warfare

Aircraft were used for reconnaissance, as fighters, bombers,

and ground-support, and each role was advanced considerably. Innovation

included airlift (the capability to quickly move limited high-priority

supplies, equipment, and personnel); and of strategic bombing (the bombing of

enemy industrial and population centers to destroy the enemy's ability to wage

war). Anti-aircraft weaponry also advanced, including defenses such as radar

and surface-to-air artillery, such as the German 88 mm gun. The use of the jet

aircraft was pioneered and, though late introduction meant it had little

impact, it led to jets becoming standard in air forces worldwide.

Advances were made in nearly every aspect of naval warfare,

most notably with aircraft carriers and submarines. Although aeronautical

warfare had relatively little success at the start of the war, actions at

Taranto, Pearl Harbor, and the Coral Sea established the carrier as the

dominant capital ship in place of the battleship.

In the Atlantic, escort carriers proved to be a vital part

of Allied convoys, increasing the effective protection radius and helping to

close the Mid-Atlantic gap. Carriers were also more economical than battleships

because of the relatively low cost of aircraft and their not requiring to be as

heavily armored. Submarines, which had proved to be an effective weapon during

the First World War, were anticipated by all sides to be important in the

second. The British focused development on anti-submarine weaponry and tactics,

such as sonar and convoys, while Germany focused on improving its offensive

capability, with designs such as the Type VII submarine and wolf pack tactics.

Gradually, improving Allied technologies such as the Leigh light, hedgehog,

squid, and homing torpedoes proved victorious.

Land warfare changed from the static front lines of World

War I to increased mobility and combined arms. The tank, which had been used

predominantly for infantry support in the First World War, had evolved into the

primary weapon. In the late 1930s, tank design was considerably more advanced

than it had been during World War I, and advances continued throughout the war

with increases in speed, armor and firepower.

At the start of the war, most commanders thought enemy tanks