|

| Canadian troops disembark from landing craft in an orderly manner onto the beachhead in Normandy. |

by C. P. Stacey

The Normandy landings of June 1944 were one of the most decisive operations of the Second World War and, indeed, one of the most significant in modern military history. The invasion of Northwest Europe marked the beginning of the final phase of the war with Germany and led, less than a year later, to the final German collapse. Canadian forces played an important part in the operation, which was tremendously complicated and on a vast scale.

Development of the Plan

In the summer of 1940 British forces were expelled from the continent of Europe, and Britain and the Commonwealth were thrown back on the defensive. The entry of the United States into the war late in 1941 made it possible to accelerate planning for a return to the continent, and American strategists were anxious to invade Northwest Europe at the earliest possible date. During 1942, however, neither trained divisions nor landing craft were available in sufficient numbers to launch such an operation successfully, even though hard-pressed Russia was urgently demanding a “Second Front” in the west. Instead, available forces were diverted to North Africa where victory was achieved in 1943.

At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 the decision was taken that the build-up of men and material for an assault upon Northwest Europe should be resumed. Lieutenant-General F. E. Morgan, a British officer, was appointed “Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (Designate)” in March, and under him an Anglo-American planning staff began work on a broad operational plan for the great invasion. The target date for the operation was 1 May 1944.

The first task facing the COSSAC planners was the selection of the area to be assaulted. Command of the sea enabled the Allies to strike almost anywhere, but short-range fighter aircraft based on England could maintain command of the air only over the enemy-held coastal sector between Flushing and Cherbourg. Study of the beaches on this coast soon narrowed the choice to two main areas: the Pas de Calais (Strait of Dover) and that from Caen to Cherbourg. Although direct assault on the Cotentin peninsula would bring the Allies the valuable port of Cherbourg, this area lacked suitable airfields and might become a dead end since the enemy could hold the neck of the peninsula with relatively light forces. The Pas de Calais offered a sea crossing of only 20 miles, good beaches, a quick turn-around for shipping and optimum air support; here, however, the German defenses were at their most formidable. This left only the Bay of the Seine, where defenses were light and the beaches of high capacity and sheltered from the prevailing winds. Its distance from the south of England would make air support less easy but the terrain, especially southeast of Caen, was suitable for airfield development. Therefore the Caen area was selected for the initial assault, the intention being to expand the foothold into a “lodgment area” to include Cherbourg and the Brittany ports.

It had long been believed that the immediate capture of a major port was essential to the success of an invasion operation; but the Dieppe raid had shown how difficult such capture was likely to be, and experience in the assault on Sicily had encouraged Allied planners to rely on the possibility of maintaining an invasion force over open beaches. In the English Channel, however, it is always necessary to count on the possibility of bad weather; and with this in view General Morgan reported that in the absence of a major port it would be necessary to improvise sheltered water somehow. He recommended that two artificial ports be made by sinking blockships. This was the origin of the famous “Mulberry” harbor.

The availability of landing craft would limit the size of the assaulting force, and General Morgan had been told that he must plan on the basis of an assault by three divisions. He aimed to land these on a front of roughly 35 miles from Caen to Grandcamp, with three tank brigades and an extra infantry brigade following on the same day. A similar shortage of transport aircraft determined that only two-thirds of an airborne division (although two had been made available) could be dropped; its main object was to be the capture of Caen. Assuming the best possible weather conditions the fifth day after the assault would find nine Allied divisions, with a proportion of armor, in the bridgehead. It was hoped that by D-plus-14 about eighteen divisions would have been landed, Cherbourg captured and the bridgehead expanded some 60 miles inland from Caen. On this basis General Morgan completed an outline plan during July 1943, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff approved it at the Quebec Conference in August.

No Supreme Commander had yet been appointed; but in December 1943 General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the American officer who had been commanding the Allied forces in the Mediterranean, was named to this post. His ground commander for the assault phase was to be the Commander-in-Chief, 21st Army Group, General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery. Both these officers were convinced that under the COSSAC plan the initial assaulting forces were too weak and committed on too narrow a front. On his arrival in London the Supreme Commander approved changes suggested by General Montgomery; subsequently these were ratified by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. To enable more landing craft to be available from production, the target date was put back to 31 May; subsequently a simultaneous landing which had been planned for the south coast of France was postponed until August. This made it possible to increase the initial assault force to five divisions supported by two follow-up divisions pre-loaded on landing craft.

The front to be assaulted was widened. On the west, it now included the beaches beyond the Vire estuary on the Cotentin peninsula, behind which it was planned to drop two American airborne divisions to speed the capture of Cherbourg; eastward it was extended somewhat to facilitate the seizure of Caen and the vital airfields in its vicinity. A British airborne division was to be dropped here to seize the crossing over the river Orne. The D-Day objectives on the British flank included Caen and Bayeux; on the American side the plan was to penetrate to the vicinity of Carentan. Thereafter, as reported later by the Supreme Commander,

...our forces were to advance on Brittany with the object of capturing the ports southward to Nantes. Our next aim was to drive east on the line of the Loire in the general direction of Paris and north across the Seine, with the purpose of destroying as many as possible of the German forces in this area of the west.

The immediate purpose, however, and the one we are concerned with here, was the establishment of bridgeheads, connected into a continuous lodgment area, to accommodate follow-up troops. This initial assault phase was known by the code name NEPTUNE. The great liberation operation as a whole was called OVERLORD. General Eisenhower’s international headquarters, which absorbed the COSSAC organization, became known as SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force).

The Enemy Situation

Allied intelligence had been able to provide a picture of German dispositions in the west which proved, in the main, to be accurate. By 3 June enemy strength in the Low Countries and France had been increased to some sixty divisions. This included troops on the Biscay coast and the Riviera. All these formations were under the Commander-in-Chief West, Field Marshal von Rundstedt. Army Group “B,” commanded by Field Marshal Rommel, included the Fifteenth Army, covering the Pas de Calais, where most German strategists believed invasion would come, and the somewhat smaller Seventh Army in Normandy and Brittany. The divisions holding the beach defenses were not of high category and had limited transport. Thus German plans to defeat invasion in the north were chiefly built around seven panzer or panzergrenadier divisions which were held in reserve. The plans have usually been considered a compromise between the views of Rundstedt, who favored defense in depth supported by strong mobile reserves and those of Rommel, who believed that the place to defeat invasion was on the beaches and therefore favored placing the reserves close up to the coast.

Hitler’s “Atlantic Wall,” though he had ordered its construction in 1942, was still far from completion as 1944 opened. Attention had been directed mainly to the ports and the Pas de Calais. After Rommel’s Army Group “B” took over the coast early in the year the defenses of other areas began to be reinforced with underwater obstacles, mines and more concrete; but in June much still remained to be done. The garrison of the assault area was also somewhat reinforced; in mid-March a good German field division appeared in the American sector. One coastal division manned almost the whole of the beaches allotted for British and Canadian assault; however, one panzer division was actually in the Caen area and two others were within a few hours’ march.

The Final Preparations

Since the middle of 1943 the air assault by RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force against German war industry (particularly aircraft production) had been gaining momentum and, at the same time, decimating the enemy fighter force which tried to oppose this strategic bombing. About three months before D-Day the air forces also began to strike at the French and Belgian railways systems to reduce enemy mobility all over Northwest Europe. Somewhat later still attacks began on tunnels and bridges with the purpose of isolating the battlefield from the rest of France.

The Seine bridges were particularly heavily hit. Those over the Loire were, with a few exceptions, left alone until after D-Day. As the Seine bridges would have been equally important had the Allies landed in the Pas de Calais, these attacks did not give the plan away.

Attacks upon enemy airfields within a radius of 130 miles from the assault area began by D-minus-21, to force the removal of German fighters to more distant bases. In order to delude the enemy, however, only a part of the bombing effort was expended against the intended assault area; the Pas de Calais and other possible landing areas continued to receive attention.

These preliminary air operations had a vital effect upon the great Allied enterprise. To them must be attributed the almost total failure of the German Air Force either to attack the great pre-invasion concentrations of men and material in southern England or to offer opposition to the actual assault. “Our D-Day experience,” General Eisenhower wrote later in his report, “was to convince us that the carefully laid plans of the German Command to oppose OVERLORD with an efficient air force in great strength were completely frustrated by the strategic bombing operations. Without the overwhelming mastery of the air which we attained by that time our assault against the continent would have been a most hazardous, if not impossible undertaking.”

It was essential to mislead the Germans as to the time and place of the Allied attack. Elaborate security precautions, including the prohibition of travel out of Britain and event the denial to ambassadors of the use of uncensored diplomatic bags, were taken to prevent information reaching the enemy; and a cover plan was adopted to encourage him to think that the Allies were going to attack the Pas de Calais. As part of this, Canadian formations were moved into the Dover area. Arrangements were made for naval and air diversions in the Channel to give the same impression.

The administrative preparations required were enormous. It was planned to land more than 175,000 men and more than 20,000 vehicles and guns in the first two days; and the requirements of the invading force in ammunition, food and supplies of every sort would be great from the beginning and would increase steadily as more troops landed. Since every unit and every item had to have a place in some ship or craft, and such a place as would enable it to perform it assigned function on the other side, very detailed administrative orders were required. To protect the camps and the depots near the embarkation ports, special air precautions and a special deployment of anti-aircraft guns were necessary; however, as previously mentioned, the anticipated enemy air attacks did not come.

The Plan of Assault

The greatest lesson drawn from the Dieppe raid of 1942 had been the necessity of overwhelming fire support for any opposed landing on a fortified coast; and the 3rd Canadian Division, in a series of exercises with the Royal Navy, had helped to work out a “combined fire plan” suitable for the task. As used on D-Day, the plan was as follows. During the night before the assault, the RAF Bomber Command attacked the ten main coastal batteries that could fire on our ships. Immediately before the landings, the U.S. Eighth Air Force attacked the beach defenses. In each case, over one thousand aircraft were used. While the Eighth was attacking, medium, light and fighter-bombers were also in action. Naval gunfire began at dawn, the bombarding force including five battleships, two monitors, nineteen cruisers and numerous destroyers; naval rockets increased the storm just before the first troops touched down, and small craft gave close gunfire support. In addition, the Army made its own contribution; its self-propelled guns fired on enemy strongpoints from their tank landing craft.

Many special devices, and particularly special armored vehicles, had been developed to assist the assault. Notable among them were the AVREs (Assault Vehicles, Royal Engineers)—tanks mounting “petards” for hurling heavy demolition charges—and the “DD” or amphibious tanks, capable of swimming in from landing craft offshore. These two types of vehicles were to lead the assault, landing before the first infantry. A night landing had been discussed, but the Navy considered daylight essential to enable it to land the troops at the correct points and to increase the accuracy of the bombardment. The landing was therefore planned for soon after dawn. It was necessary that it should take place at a period of relatively low but rising tide, so that the beach obstacles would be exposed and the landing craft would not become stranded; and for the airborne operations during the night before the assault moonlight was desirable. The necessary combination of conditions would exist on 5 June and the two following days, and the 5th was accordingly designated D-Day.

D-Day: The Assault

As 5 June approached everything seemed ready. The Allied Expeditionary Force had thirty-seven divisions available—and others would move direct from the United States to France once ports had been captured. Under General Montgomery’s headquarters, the First U.S. Army was to assault on the right and the Second British Army on the left. The 5th U.S. Corps planned to use a regimental combat team of each of its two divisions on Omaha Beach, while the 7th U.S. Corps attacked Utah Beach with one division. In the British sector, the 30th Corps was on the right, with one division assaulting; on the left was the 1st Corps with two divisions. One of these was the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, on Juno Beach; though the First Canadian Army had been designated a “follow-up” formation, Canada would be represented in the first landing by this division, supported by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. On its right was the 50th (Northumbrian) Division, on Gold Beach, and on its left the 3rd British Division on Sword Beach. British Commandos and American Rangers were given subsidiary objectives along the coast. The 6th British Airborne Division had the airborne task on the eastern flank and the 82nd and 101st U.S. Airborne Divisions those in the west.

Everything was ready—except the weather. On 4 June the meteorological report was so discouraging that General Eisenhower decided to postpone the operation for twenty-four hours. Next day, although conditions were still very far from ideal, the meteorologists predicted a temporary improvement; and on this basis the Supreme Commander took the heavy responsibility of deciding that the operation would proceed on the morning of the 6th.

Operation NEPTUNE began shortly before midnight, when the RAF commenced to pound the coastal batteries. Soon after midnight the men of the three airborne divisions began to land in Normandy. All were much more widely scattered than had been planned, but were nevertheless able to carry out their essential tasks, protecting the flanks of the seaborne landings and spreading confusion among the enemy. On the British side the 6th Airborne Division (which included a Canadian battalion) seized bridges over the Orne and the nearby canal intact, captured a coastal battery and carried out demolitions to cover this flank. With the coming of daylight the great bombardment of the beach defenses began. Clouds forced the U.S. heavy bombers to do without direct observation, and their anxiety to avoid hitting the Allied landing craft resulted in many bombs coming down too far inland. The naval bombardment likewise scored direct hits on only a small proportion of the enemy positions. Yet this terrific pounding of the whole defense area had a powerful morale effect on the Germans, and there is no doubt that it went far to enable the Allied troops to breach the Atlantic Wall at a much lower cost in casualties than had been expected. At many points Allied units got ashore without coming under really heavy fire, although fierce fighting was required afterwards to reduce strongpoints which the bombardment had not destroyed.

The roughness of the sea somewhat upset the timetable. Some of the craft carrying the special armor were late, some of the DD tanks could not be launched, and the infantry themselves were delayed in landing. Yet in general the attack went well, and before the morning was far advanced the Allied troops were pushing inland, by-passing the strongpoints that still held out. Nevertheless, stubborn German resistance kept them from attaining their final D-Day objectives before evening at any point, except for a few Canadian tanks that reached them and then withdrew. The situation was worst in the Omaha area, where there were German field troops and a steep coast. For two days the Americans had to fight desperately to keep a foothold, and casualties here were three times what they were elsewhere. The Canadian division had 335 fatal casualties on D-Day, somewhat fewer than had been expected.

The Allies had achieved strategic and even tactical surprise; that is, not only had the German high command had no time to reinforce the threatened area, but even the units holding it had no warning until the Allies bombardment opened. However, the German reaction was rapid, even though there was delay in getting Hitler’s permission to move some of the reserve panzer divisions. A tank counterattack on D-Day, although beaten back, helped to prevent the 3rd British Division from getting Caen. The next morning the 50th Division took Bayeux, and the 3rd Canadian Division got its right brigade on to the final objective (the Caen-Bayeux road and railway)—the first brigade in the Second Army to do so; but the left brigade was struck by one of the reserve panzer divisions and driven back. The Germans regarded the Caen area from the beginning as the point of greatest danger and the pivot of their defense in Normandy. By throwing their reserves in piecemeal in that area as they came up, they temporarily stabilized the situation there; but they were never able to build up a striking force equal to delivering a large-scale counteroffensive and really threatening the Allied bridgehead. The movement of their reserves was most seriously hampered by the havoc which the air forces had wrought upon their communications, and by continuing air attacks; while the Allies, their sea communications protected by their navies and air forces, poured men and material into the bridgehead, hampered only by unseasonable bad weather. Above all, the Germans had been deceived into the belief that the main Allied attack was still to come—in the Pas de Calais; and there the Fifteenth Army, whose infantry divisions might have turned the scale in Normandy, sat idle while the British and American bridgehead was steadily built up.

Consolidation of the Bridgehead

The days following D-Day were spent in linking the various Allied footholds into a continuous and secure lodgment area. With good naval and air support, the hard-pressed Americans on Omaha gradually deepened their penetration and on 9 June they were able to take the offensive effectively. By that time the bridgeheads were linked up all along the front of assault except for a gap between the two American sectors near Carentan. Contact was made across this the next day, and after stiff fighting Carentan itself was captured on 12-13 June. On the British front the Germans went on throwing in fierce local armored attacks; on 8 June, for instance, the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade beat off a serious threat and continued to hold its position on the final D-Day objective. Caen remained in German hands, but the eastern flank of the bridgehead, though much more contracted than had been planned, was secure.

By 12 June the first phase of Operation OVERLORD had been successfully completed. The Allies had established a firm foothold on the continent. Some 325,000 men, 55,000 vehicles and 105,000 tons of stores had already been brought ashore. The construction of the artificial harbors, on a more elaborate plan than that projected by COSSAC, was well advanced. The Germans’ plan of defense had failed; they had not driven the invaders into the sea, and had now to prepare for their inevitable attempt to break out from the bridgehead.

Comments

By 1944 the western democracies, unprepared when war broke out, had built up their strength to the point where they could challenge the enemy with confidence. It seemed clear, however, that the only way of obtaining a rapid decision was by defeating the main German armies on a European battlefield. The necessary preliminary to this was the crossing of the Channel and the establishment of a bridgehead, carried out in the teeth of strong defenses and an experienced and determined enemy. This was such a hazardous operation that many good judges on the Allied side felt very uncertain about the outcome. That the invasion succeeded was due to the fact that the Allies were able to mobilize sea, land and air power on a vast scale, but even more to the fact that as a result of remarkably skillful and thorough planning they were able to use that power to the best advantage.

Every one of the accepted principles of war is illustrated in Operation NEPTUNE. Eisenhower was told to enter Europe and “undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.” The special aim in the assault phase was “to secure a lodgment on the continent from which further offensive operations can be developed.” These great simple objectives were never lost sight of and formed the foundation of the whole plan, a good example of sound selection and maintenance of the aim. The ultimate object was achieved eleven months after D-Day.

It is clear that the achievement of surprise played a very great part in the initial success. The enemy was completely deceived as to the Allied intentions, and continued to grope in the dark long after D-Day. This helped the Allies to effect a destructive concentration of force at the decisive point, while great German forces elsewhere waited for attacks that never came. The related principle of economy of effort, the result of “balanced employment of forces” and “judicious expenditure of all resources,” is equally clearly illustrated.

Where could a better example of cooperation be found than in NEPTUNE? The victory won on the coast of lower Normandy was the result of the efforts of the three fighting services of three different nations, working smoothly in combination under a Supreme Commander acknowledged to have a special genius for coordination. The point does not require to be labored. “Goodwill and the desire to cooperate” paid their usual dividends, on this as on lesser occasions.

Similarly, it is clear that the Allied victory was largely a triumph of administration. To get the invading force to France, and to maintain it when there, required, as has been seen, extraordinarily thorough administrative planning and a tremendous mobilization of human and material resources. The prefabricated harbors, brought across the Channel and assembled on the invasion coast, may stand as symbols of the administrative ingenuity which made such a great contribution to this epoch-making victory.

Other principles can be briefly dealt with. Offensive action speaks for itself. NEPTUNE is the very embodiment of it. As for maintenance of morale, only troops of high morale could have carried out the task, for it was actually more formidable in prospect than it turned out to be in reality; on the other hand, the famous Atlantic Wall once broken, success, as always, encouraged the Allied troops to push on to further victories. Security of the base and the lines of communication was well provided for by the navy, the air forces and the anti-aircraft gunners; however, as it turned out, the enemy was in no state to threaten them. Similarly, flexibility was less important in this operation in that the plan as written succeeded so well; it appears chiefly in the use of those very flexible weapons, naval and air power, to support the troops ashore at any point during the bridgehead campaign where they found themselves hard pressed.

Bibliography

American Forces in Action Series: Omaha Beachhead (6 June-13 June 1944). Washington, 1945.

—: Utah Beach to Cherbourg (6 June-27 June 1944). Washington, 1947.

W. F. Craven and J. L. Cate. The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. III. Chicago, 1951.

General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower. Crusade in Europe. New York, 1948.

—. Report by the Supreme Commander to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the Operations in Europe of the Allied Expeditionary Force, 6 June 1944 to 8 May 1945. London and Washington, 1946.

Major General Sir Francis de Guingand. Operation Victory. London, 1947.

Gordon A. Harrison. Cross-Channel Attack (United States Army in World War II: The European Theater of Operations). Washington, 1951.

Field-Marshal Viscount Montgomery. Normandy to the Baltic. London, 1947.

Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Morgan. Overture to Overlord. London, 1950.

Colonel C. P. Stacey. The Victory Campaign (Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Vol. III). Ottawa, 1960.

|

| Map of Allied concentration and routes, June 6, 1944. |

|

| Juno and Gold Beaches, June 6, 1944. |

|

| Map of North Shores and Queen's Own Rifles (3rd Canadian Infantry Division) landings at St. Aubin-sur-mer and Bernieres-sur-mer on Juno Beach (Nan Beach). |

|

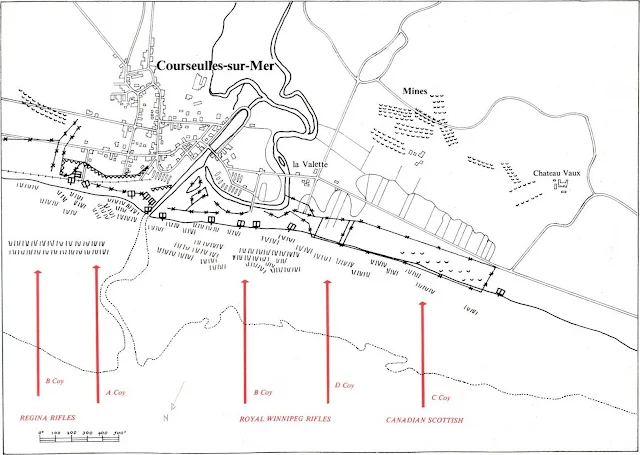

| Map of Regina Rifles, Royal Winnipeg Rifles, and Canadian Scottish (3rd Canadian Infantry Division) landings at Courseulles-sur-Mer on Juno Beach (Mike Beach). |

|

| Map of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division front line positions at midnight June 6. |

|

| German Forces and Defenses: 716th Infantry Division Area, June 6, 1944. |

|

| Map of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division landings on Juno Beach showing D-Day objectives ("Yew", "Elm", "Oak" ) and front line at midnight June 6. |

|

| Map of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division landings on Juno Beach showing D-Day objectives ("Yew", "Elm", "Oak" ) and advance of 1st Hussars, Fort Garry Horse and Sherbrooke Fusiliers tank regiments. |

|

| Canadian soldiers study a German plan of the beach for the D-Day landing operations in Normandy on June 6, 1944. |

|

| Troops of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division going ashore from assault landing craft at East Wittering, Sussex, during Exercise FABIUS III, April 23 to 7 May 1944. |

|

| HMCS Prince Henry Anchored in Greenock; May 1944. |

|

| Assault landing craft leaving HMCS Prince Henry during a training exercise in May 1944. |

|

| Assault landing craft leaving HMCS Prince Henry during the same training exercise in May 1944. |

|

| Assault landing craft leaving HMCS Prince Henry during the same training exercise in May 1944. |

|

| Infantrymen going ashore from the HMCS Prince Henry, June 6, 1944. |

|

| Infantrymen going ashore from the HMCS Prince Henry, June 6, 1944. |

|

| The same landing craft and infantry as seen in the previous photo now going ashore. |

|

| Personnel of Royal Canadian Navy Beach Commando "W" landing on Mike Beach, Juno sector of the Normandy beachhead, France; July 8, 1944. |

|

| Vertical aerial photograph of the landings on Mike beach, Juno area, at Courselles-sur-Mer, 6 June 1944. |

|

| Vertical aerial photograph of the landings on Mike beach, Juno area, to the west of Courselles-sur-Mer, 6 June 1944. |

|

| LCI(L)s (Landing Craft Infantry Large) about to disembark troops of 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade onto Nan White beach, Juno area, at Bernieres-sur-Mer, late morning, 6 June 1944. |

|

| Watching from the HMCS Prince David, as the assault craft heads ashore, June 6, 1944. |

|

| A German machine gun nest along the Atlantic Wall, background, was captured by Canadian troops on June 8, 1944, following the D-Day invasion. |

|

| Private D. D. Martin on sentry duty along the Normandy beachhead on June 10, 1944. |

|

| Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière resting behind a Universal Carrier in a low ground position along the Normandy beachhead in June 1944. |

|

| (Left to Right) Lieutenant E. M. Peto, Company Sergeant-Major Charlie Martin and Rifleman N. E. Lindenas, preparing to lay a minefield in Bretteville-Orgueilleuse, France, June 20, 1944. |

|

| Canadian Tank Destroyer crews removing the waterproofing kits from their tanks after landing in Normandy, June 1944. |

|

| Canadian tanks firing into German positions in Normandy, 8-9 June 1944. |

|

| Canadian soldiers guard German prisoners captured on the Normandy beachhead. |

|

| Canadian troops land at Juno Beach, Courseulles-sur-Mer, Normandy, on June 6, 1944. |

|

| Canadian infantry going ashore during the Normandy invasion. |

|

| Canadian infantrymen landing on a beach in Normandy. |

|

| Canadian soldiers in amphibious tank arriving in Normandy, June-July 1944. |

|

| Unfurling of the Canadian flag at 1st Canadian Army Headquarters on Dominion Day; the first time that the Canadian flag flew on French soil after D-Day. Normandy, France, 29 June 1944. |

|

| RSM Rutherford raising the first Canadian flag to fly in Caen, France, 11 July 1944. |

No comments:

Post a Comment