|

| Circa 1944-45: Dragon's teeth near Brandscheid. The wooded section at upper left is the edge of the Schnee Eifel. |

The Siegfried Line, known in German as the Westwall (western bulwark), was a German defensive line built during the late 1930s. Started in 1936, opposite the French Maginot Line, it stretched more than 630 km (390 mi) from Kleve on the border with the Netherlands, along the western border of Nazi Germany, to the town of Weil am Rhein on the border with Switzerland. The line featured more than 18,000 bunkers, tunnels and tank traps.

From September 1944 to March 1945, the Siegfried Line was subjected to a large-scale Allied offensive.

The official German name for the defensive line construction program before and during the Second World War changed several times during the late 1930s. It came to be known as the "Westwall", but in English it was referred to as the "Siegfried Line" or, sometimes, the "West Wall". Various German names reflected different areas of construction:

Border Watch program (pioneering program) for the most advanced positions (1938)

Limes program (1938)

Western Air Defense Zone (1938)

Aachen–Saar program (1939)

Geldern Emplacement between Brüggen and Kleve (1939–1940)

The programs were given the highest priority, putting a heavy demand on the available resources.

The origin of the name "Westwall" is unknown, but it appeared in popular use from the middle of 1939. There is a record of Hitler sending an Order of the Day to soldiers and workers at the "Westwall" on 20 May 1939.

At the start of World War II, the Siegfried Line had serious weaknesses. After the war, German General Alfred Jodl said that it had been "little better than a building site in 1939" and, when Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt inspected the line, the weak construction and inadequate weapons caused him to laugh. Despite France's declaration of war against Germany in September 1939, there was no major combat involving the Siegfried Line at the start of the campaign in the West, except for a minor offensive by the French. Instead, both sides remained in a safe position behind their defenses, during the so-called Phoney War.

The Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda drew foreign attention to the unfinished Westwall, in several instances showcasing incomplete or test positions to portray the project finished and ready for action. During the Battle of France, French forces made minor attacks against some parts of the line, but the majority was left untested in battle. When the campaign finished, transportable weapons and materials, such as metal doors, were removed from the Siegfried Line and used in other places such as the Atlantic Wall defenses. The concrete sections were left in place in the countryside and soon became completely unfit for defense. The bunkers were used for storage instead.

With the D-Day landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944, war in the West broke out once more. On 24 August 1944, Hitler gave a directive for renewed construction on the Siegfried Line. 20,000 forced laborers and members of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service), most of whom were 14 to 16-year-old boys, attempted to re-equip the line for defensive purposes. Local people were also called in to carry out work, mostly building anti-tank ditches.

Even during construction, it was becoming clear that the bunkers could not withstand newly developed amour-piercing weapons. At the same time as the reactivation of the Siegfried Line, small concrete "Tobruks" were built along the borders of the occupied area. Those bunkers were mostly dugouts for single soldiers.

In August 1944, the first clashes took place on the Siegfried Line. The section of the line where most fighting took place was the Hürtgenwald (Hürtgen Forest) area in the Eifel, 20 km (12 mi) south-east of Aachen. The Aachen Gap was the logical route into Germany's Rhineland and its main industrial area, so it was where the Germans concentrated their defense.

The Americans committed an estimated 120,000 troops plus reinforcements to the Battle of Hürtgen Forest. The battle in the heavily forested area claimed the lives of 24,000 American soldiers, along with 9,000 so-called non-battle casualties — those evacuated because of fatigue, exposure, accidents and disease. The German death toll is not documented. After the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, the Battle of the Bulge began, a last-ditch attempt by the Germans to reverse the course of the war in the West. The offensive started in the area south of the Hürtgenwald, between Monschau and the Luxembourgish town of Echternach. German loss of life and material was severe and the effort failed. There were serious clashes along other parts of the Siegfried Line and defending soldiers in many bunkers refused to surrender, often fighting to the death. By early 1945, the last Siegfried Line bunkers had fallen at the Saar and Hunsrück.

The British 21st Army Group, which included US formations, also attacked the Siegfried Line. The resulting fighting brought total US losses to approximately 68,000. In addition, the First Army incurred over 50,000 non-battle casualties and the Ninth Army over 20,000. That brought the overall cost of the Siegfried Line Campaign, in US personnel, close to 140,000.

During the post-war period, many sections of the Siegfried Line were removed using explosives.

In North Rhine Westphalia, about thirty bunkers still remain. Most of the rest were either destroyed with explosives or covered with earth. Tank traps still exist in many areas and, in the Eifel, they run over several kilometers. Zweibrücken Air Base was built on top of the Siegfried Line. When the base was still open, the remnants of several old bunkers could be seen in the tree line near the main gate. Another bunker was outside the base perimeter fence near the base hospital. Once the base was closed, workers, digging up the base's fuel tanks, discovered lost bunkers buried below the tanks.

Since 1997, with the motto "The value of the unpleasant as a memorial" (Der Denkmalswert des Unerfreulichen), an effort has been made to preserve the remains of the Siegfried Line as a historical monument. It was intended to stop reactionary fascist groups from using the Siegfried Line for propaganda purposes.

At the same time, state funding was still being provided to destroy the remains of the Siegfried Line. Consequently, emergency archaeological digs took place whenever any part of the line was to be removed, for example for road building. Archaeological activity was not able to stop the destruction of those sections, but furthered scientific knowledge and revealed details of the line's construction.

Nature conservationists consider the remains of the Siegfried Line valuable as a chain of biotopes where, thanks to its size, rare animals and plants can take refuge and reproduce. That effect is magnified by the fact that the concrete ruins cannot be used for agricultural or forestry purposes.

Westwall Construction Programs

Small bunkers with 50 cm (20 in) thick walls were set up with three embrasures towards the front. Sleeping accommodations were hammocks. In exposed positions, similar small bunkers were erected with small round armored "lookout" sections on the roofs. The program was carried out by the Border Watch (Grenzwacht), a small military troop activated in the Rhineland immediately after the region was re-militarized by Germany from 1936 onwards, after having been de-militarized following the First World War.

The Limes program began in 1938 following an order by Hitler to strengthen fortifications on the western German border. Limes refers to the former borders of the Roman Empire; the cover story for the program was that it was an archaeological study.

Its Type 10 bunkers were more strongly constructed than the earlier border fortifications. These had 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) thick ceilings and walls. A total of 3,471 were built along the entire length of the Siegfried Line. They featured a central room or shelter for 10–12 men with a stepped embrasure facing backwards and a combat section 50 cm (20 in) higher. This elevated section had embrasures at the front and sides for machine guns. More embrasures were provided for riflemen, and the entire structure was constructed so as to be safe against poison gas.

Heating was from a safety oven, the chimney of which was covered with a thick grating. Space was tight, with about 1 m2 (11 sq ft) per soldier, who was given a sleeping-place and a stool; the commanding officer had a chair. Surviving examples still retain signs warning "Walls have ears" and "Lights out when embrasures are open!"

The Aachen-Saar program bunkers were similar to those of the Limes program: Type 107 double MG casemates with concrete walls up to 3.5 m (11 ft) thick. One difference was that there were no embrasures at the front, only at the sides of the bunkers. Embrasures were only built at the front in special cases and were then protected with heavy metal doors. This construction phase included the towns of Aachen and Saarbrücken, which were initially west of the Limes Program defense line.

The Western Air Defence Zone (Luftverteidigungszone West or LVZ West) continued parallel to the two other lines toward the east and consisted mainly of concrete flak foundations. Scattered MG 42 and MG 34 emplacements added additional defense against both air and land targets. Flak turrets were designed to force enemy planes to fly higher, thus decreasing the accuracy of their bombing. These towers were protected at close range by bunkers from the Limes and Aachen-Saar programs.

The Geldern Emplacement lengthened the Siegfried Line northwards as far as Kleve on the Rhine and was built after the start of the Second World War. The Siegfried Line originally ended in the north near Brüggen in the Viersen district. The primary constructions were unarmed dugouts, but their extremely strong concrete design afforded excellent protection to the occupants. For camouflage they were often built near farms.

Standard construction elements such as large Regelbau bunkers, smaller concrete "pillboxes", and "dragon's teeth" anti-tank obstacles were built as part of each construction phase, sometimes by the thousands. Frequently vertical steel rods would be interspersed between the teeth. This standardization was the most effective use of scarce raw materials, transport and workers, but proved an ineffective tank barrier as US bulldozers simply pushed bridges of soil over these devices.

"Dragon's teeth" tank traps were also known as Höcker in German ('humps' or 'pimples' in English) because of their shape. These blocks of reinforced concrete stand in several rows on a single foundation. There are two typical sorts of barrier: Type 1938 with four rows of teeth getting higher toward the back, and Type 1939 with five rows of such teeth. Many other irregular lines of teeth were also built. Another design of tank obstacle, known as the Czech hedgehog, was made by welding together several bars of steel in such a way that any tank rolling over it would get stuck and possibly damaged. If the contour of the land allowed it, water-filled ditches were dug instead of tank traps. Examples of this kind of defense are those north of Aachen near Geilenkirchen.

The early fortifications were mostly built by private firms, but the private sector was unable to provide the number of workers needed for the programs that followed; this gap was filled by the Todt Organization. With this organization’s help, huge numbers of forced laborers – up to 500,000 at a time – worked on the Siegfried Line. Transport of materials and workers from all across Germany was managed by the Deutsche Reichsbahn railway company, which took advantage of the well-developed strategic railway lines built on Germany's western border in World War I.

Working conditions were highly dangerous. For example, the most primitive means had to be used to handle and assemble extremely heavy armor plating, weighing up to 60 tonnes (66 short tons).

Life on the building site and after work was monotonous, and many people gave up and left. Most workers received the West Wall Medal for their service.

German propaganda, both at home and abroad, repeatedly portrayed the Westwall during its construction as an unbreachable bulwark. At the start of the war, the opposing troops remained behind their own defense lines.

As a morale booster for British troops marching off to France, the Siegfried Line was the subject of a popular song: "We're Going to Hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line". A French version by Ray Ventura ("On ira pendre notre linge sur la ligne Siegfried") met a great success during the Phoney War (Drôle de guerre).

When asked about the Siegfried Line, General George S. Patton reportedly said "Fixed fortifications are monuments to man's stupidity."

Further Reading

Andrews, Ernest A.; Hurt, David B. (2022). A Machine Gunner's War: From Normandy to Victory with the 1st Infantry Division in World War II. Philadelphia & Oxford: Casemate.

Kauffmann, J.E. and Jurga, Robert M. Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II, Da Capo Press, 2002.

MacDonald, Charles B. (1963) [1990]. The Siegfried Line Campaign. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

Makos, Adam (2019). Spearhead (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 7, 48, 49–50, 54, 62, 225, 236.

|

| Tank obstacle of the Siegfried Line near Aachen, Germany. |

|

| US Army soldiers move across tank obstacles of the Siegfried Line. |

|

| Map of the Siegfried Line. |

|

| Front line in December 1944. |

|

| American soldiers cross the Siegfried Line and march into Germany. |

|

| U.S. soldiers pause for a rest among the ruins of the Siegfried Line in the Rhine Valley, February 1945. |

|

| Bunker ruins near Aachen. |

|

| Ruins of a bunker on the Siegfried Line. |

|

| The Siegfried Line as a chain of biotopes. |

|

| Tank obstacle of the Siegfried Line nearby Aachen in Germany. |

|

| Water-filled trench near Geilenkirchen. |

|

| Remains of Type 10 Limes program bunker seen from the rear near Aachen, Germany. |

|

| Geldern Emplacement bunker near Kleve. |

|

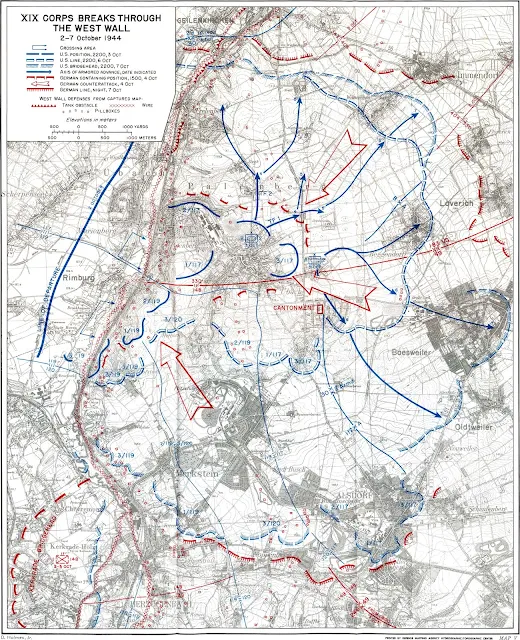

| October 2-7, 1944: XIX Corps Breaks Through the West Wall: Battle of Aachen. |

|

| Plan of typical Siegfried Line pillbox. |

|

| September 1939: German soldiers on the shore of the Upper Rhine, next to a bunker. |

|

| September 23, 1939: German soldiers on the shore of the Upper Rhine, next to a bunker. |

|

| October 1938: Construction of Westwall anti-tank ditches and fortifications through a valley. |

|

| October 1938: Formworks and concrete mixers at a construction site for bunkers. |

|

| West Wall: Entrance to an anti-tank gun position disguised as a fire station. |

|

| Prefabricated curved anti-tank obstacles. |

|

| March 3, 1940: West Wall. Railway barrier consisting of steel barriers, piles and Czech hedgehogs. |

|

| Circa 1944-45: Dragon's teeth near Brandscheid. The wooded section at upper left is the edge of the Schnee Eifel. |