The naval Battle of the Eastern Solomons (also known as the Battle of the Stewart Islands and, in Japanese sources, as the Second Battle of the Solomon Sea), took place on 24–25 August 1942, and was the third carrier battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II and the second major engagement fought between the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy during the Guadalcanal Campaign. As at the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway, the ships of the two adversaries were never within sight of each other. Instead, all attacks were carried out by carrier-based or land-based aircraft.

After several damaging air attacks, the naval surface combatants from both America and Japan withdrew from the battle area without either side securing a clear victory. However, the U.S. and its allies gained tactical and strategic advantage. Japan’s losses were greater and included dozens of aircraft and their experienced aircrews. Also, Japanese reinforcements intended for Guadalcanal were delayed and eventually delivered by warships rather than transport ships, giving the Allies more time to prepare for the Japanese counteroffensive and preventing the Japanese from landing heavy artillery, ammunition, and other supplies.

Background

On 7 August 1942, Allied forces (primarily U.S. Marine Corps units) landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases to threaten supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and secure the islands as launching points for a campaign with an eventual goal of isolating the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.

The Allied landings were directly supported by three U.S. aircraft carrier task forces (TFs): TF 11 (USS Saratoga), TF 16 (USS Enterprise), and TF 18 (USS Wasp), their respective air groups, and supporting surface warships, including a battleship, cruisers, and destroyers. The overall commander of the three carrier task forces was Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, who flew his flag on Saratoga. The aircraft from the three carriers provided close air support for the invasion forces and defended against Japanese air attacks from Rabaul. After a successful landing, they remained in the South Pacific area charged with four main objectives: guarding the line of communication between the major Allied bases at New Caledonia and Espiritu Santo; giving support to Allied ground forces at Guadalcanal and Tulagi against possible Japanese counteroffensives; covering the movement of supply ships aiding Guadalcanal; and engaging and destroying any Japanese warships that came within range.

Between 15 and 20 August, the U.S. carriers covered the delivery of fighter and bomber aircraft to the newly opened Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. This small, hard-won airfield was a critical point in the entire island chain, and both military sides strategically considered that control of the airbase offered potential control of the local battle area airspace. In fact, Henderson Field and the aircraft based upon it soon resulted in telling effects on the movement of Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands and in the attrition of Japanese air forces in the South Pacific Area. Historically, Allied control of Henderson Field became the key factor in the entire battle for Guadalcanal.

Surprised by the Allied offensive in the Solomons, Japanese naval forces (under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto) and army forces prepared a counteroffensive, with the goal of driving the Allies out of Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The counteroffensive was called Operation Ka. (Kana Ka is the root of kana ga, the first syllable in Gadarukanaru, the Japanese name for Guadalcanal.) The naval forces had the additional objective of destroying Allied warship forces in the South Pacific area, specifically the U.S. carriers.

Battle

Prelude

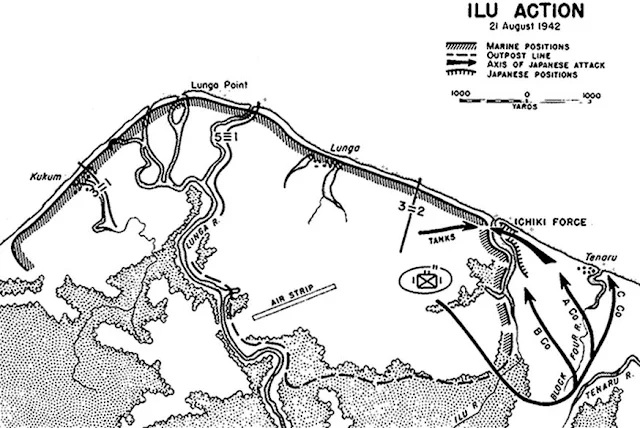

On 16 August 1942, a convoy of three slow transport ships loaded with 1,411 Japanese soldiers from the 28th “Ichiki” Infantry Regiment as well as several hundred naval troops from the 5th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), departed the major Japanese base at Truk Lagoon (Chuuk) and headed towards Guadalcanal. The transports were guarded by light cruiser Jintsū, eight destroyers, and four patrol boats, led by Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka (flag in Jintsū) Also departing from Rabaul to help protect the convoy was a “close cover force” of four heavy cruisers from the 8th Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa. These were the same, relatively old, heavy cruisers that had defeated an Allied naval surface force in the earlier Battle of Savo Island (with the subtraction of the Kako, which had been sunk by an American submarine). Tanaka planned to land the troops from his convoy on Guadalcanal on 24 August.

On 21 August, the rest of the Japanese Ka naval force departed Truk, heading for the southern Solomons. These ships were basically divided into three groups: the “main body” contained the Japanese carriers—Shōkaku and Zuikaku, light carrier Ryūjō, and a screening force of one heavy cruiser and eight destroyers, commanded by Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo in Shōkaku; the “vanguard force” consisted of two battleships, three heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and three destroyers, commanded by Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe; the “advanced force” contained five heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, six destroyers, and the seaplane carrier Chitose, commanded by Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondō. Finally, a force of about 100 IJN land-based bombers, fighters, and reconnaissance aircraft at Rabaul and nearby islands were positioned for operational support. Nagumo’s main body positioned itself behind the “vanguard” and “advanced” forces in an attempt to more easily remain hidden from U.S. reconnaissance aircraft.

The Ka plan dictated that once U.S. carriers were located, either by Japanese scout aircraft or an attack on one of the Japanese surface forces, Nagumo’s carriers would immediately launch a strike force to destroy them. With the U.S. carriers destroyed or disabled, Abe’s “vanguard” and Kondo’s “advanced” forces would close with and destroy the remaining Allied naval forces in a warship surface action. This would then allow Japanese naval forces the freedom to neutralize Henderson Field through bombardment while covering the landing of the Japanese army troops to retake Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

In response to an unanticipated land battle fought between U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal and Japanese forces on 19–20 August, the U.S. carrier task forces under Fletcher reversed towards Guadalcanal from their positions 400 mi (350 nmi; 640 km) to the south on 21 August. The U.S. carriers were to support the Marines, protect Henderson Field, engage the enemy and destroy any Japanese naval forces that arrived to support Japanese troops in the land battle on Guadalcanal.

Both Allied and Japanese naval forces continued to converge on 22 August and both sides conducted intense aircraft scouting efforts, however neither side spotted its adversary. The disappearance of at least one of their scouting aircraft (shot down by aircraft from Enterprise before it could send a radio report), caused the Japanese to strongly suspect that U.S. carriers were in the immediate area. The U.S., however, was unaware of the disposition and strength of approaching Japanese surface warship forces.

At 09:50 on 23 August, a U.S. PBY Catalina flying boat (based at Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands) initially sighted Tanaka’s convoy. By late afternoon, with no further sightings of Japanese ships, two aircraft strike forces from Saratoga and Henderson Field took off to attack the convoy. However, Tanaka, knowing that an attack would be forthcoming following the PBY sighting, reversed course once he had departed the area, and eluded the strike aircraft. After Tanaka reported to his superiors his loss of time by turning north to avoid the expected Allied airstrike, the landings of his troops on Guadalcanal was pushed back to 25 August. By 18:23 on 23 August, with no Japanese carriers sighted and no new intelligence reporting of their presence in the area, Fletcher detached Wasp (which was getting low on fuel) and the rest of TF 18 for the two-day trip south toward Efate Island to refuel. Thus, Wasp and her escorting warships missed the upcoming battle.

Carrier Action on August 24

At 01:45 on 24 August 1942, Nagumo ordered Rear Admiral Chūichi Hara (with the light carrier Ryūjō, the heavy cruiser Tone and destroyers Amatsukaze and Tokitsukaze) to proceed ahead of the main Japanese force and send an aircraft attack force against Henderson Field at daybreak. The Ryūjō mission was most likely in response to a request from Nishizō Tsukahara (the naval commander at Rabaul) for help from the combined fleet in neutralizing Henderson Field. The mission may also have been intended by Nagumo as a feint maneuver to divert U.S. attention allowing the rest of the Japanese force to approach the U.S. naval forces undetected as well as to help provide protection and cover for Tanaka’s convoy. Most of the aircraft on Shōkaku and Zuikaku were readied to launch on short notice if the U.S. carriers were located. Between 05:55 and 06:30, the U.S. carriers (mainly Enterprise augmented by PBY Catalinas from Ndeni) launched their own scout aircraft to search for the Japanese naval forces.

At 09:35, a Catalina made the first sighting of the Ryūjō force. Later that morning, several more sightings of Ryūjō and ships of Kondo’s and Mikawa’s forces by carrier and other U.S. reconnaissance aircraft followed. Throughout the morning and early afternoon, U.S. aircraft also sighted several Japanese scout aircraft and submarines, leading Fletcher to believe that the Japanese knew where his carriers were, which actually was not yet the case. Still, Fletcher hesitated to order a strike against the Ryūjō group until he was sure there were no other Japanese carriers in the area. Finally, with no firm word on the presence or location of other Japanese carriers, at 13:40 Fletcher launched a strike of 38 aircraft from Saratoga to attack Ryūjō. However, he kept aircraft in reserve from both U.S. carriers potentially ready should any Japanese fleet carriers be sighted.

Meantime, at 12:20, Ryūjō launched six Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” bombers and 15 A6M3 Zero fighters to attack Henderson Field in conjunction with an attack by 24 Mitsubishi G4M2 “Betty” bombers and 14 Zeros from Rabaul. However, unknown to the Ryūjō aircraft, the Rabaul aircraft had encountered severe weather and returned to their base earlier at 11:30. The Ryūjō aircraft were detected on radar by Saratoga as they flew toward Guadalcanal, further fixing the location of their ship for the impending U.S. attack. The Ryūjō aircraft arrived over Henderson Field at 14:23, and tangled with Henderson’s fighters (members of the Cactus Air Force) while bombing the airfield. In the resulting engagement, three “Kates,” three Zeros, and three U.S. fighters were shot down, and no significant damage was done to Henderson Field.

Almost simultaneously, at 14:25 a Japanese scout aircraft from the cruiser Chikuma sighted the U.S. carriers. Although the aircraft was shot down, its report was transmitted in time, and Nagumo immediately ordered his strike force launched from Shōkaku and Zuikaku. The first wave of aircraft (27 Aichi D3A2 “Val” dive bombers and 15 Zeros) was off by 14:50 and on its way toward Enterprise and Saratoga. Coincidentally about this same time, two U.S. scout aircraft finally sighted the main Japanese force. However, due to communication problems, these sighting reports never reached Fletcher. Before leaving the area, the two U.S. scout aircraft attacked Shōkaku, causing negligible damage. At 16:00 a second wave of 27 Vals and nine Zeros was launched by the Japanese carriers and headed south toward the U.S. carriers. Abe’s “Vanguard” force also surged ahead in anticipation of meeting the U.S. ships in a surface action after nightfall.

Again coincidentally about this same time, the Saratoga strike force arrived and attacked Ryūjō, hitting and heavily damaging her with three to five bombs and perhaps one torpedo, and killing 120 of her crew. Also during this time, several U.S. B-17 heavy bombers attacked the crippled Ryūjō but caused no additional damage. The crew abandoned the heavily damaged Japanese carrier at nightfall and she sank soon after. Amatsukaze and Tokitsukaze rescued Ryūjō’s survivors and the aircrews from her returning strike force, who ditched their aircraft in the ocean nearby. After the rescue operations were complete, both Japanese destroyers and Tone rejoined Nagumo’s main force.

At 16:02, still waiting for a definitive report on the location of the Japanese fleet carriers, the U.S. carriers’ radar detected the first incoming wave of Japanese strike aircraft. Fifty-three F4F-4 Wildcat fighters from the two U.S. carriers were directed by radar control towards the attackers. However, communication problems, limitations of the aircraft identification capabilities of the radar, primitive control procedures, and effective screening of the Japanese dive bombers by their escorting Zeros, prevented all but a few of the U.S. fighters from engaging the Vals before they began their attacks on the U.S. carriers. Just before the Japanese dive bombers began their attacks, Enterprise and Saratoga cleared their decks for the impending action by launching the aircraft that they had been holding ready in case the Japanese fleet carriers were sighted. These aircraft were told to fly north and attack anything they could find, or else to circle outside the battle zone, until it was safe to return.

At 16:29, the Japanese dive bombers began their attacks. Although several attempted to set up to attack the Saratoga, they quickly shifted back to the nearer carrier, Enterprise. Thus, Enterprise was the target of almost the entire Japanese air attack. Several Wildcats followed the Vals into their attack dives, despite the intense anti-aircraft artillery fire from Enterprise and her screening warships, in a desperate attempt to disrupt their attacks. As many as four Wildcats were shot down by U.S. anti-aircraft fire, as well as several Vals.

Because of the effective anti-aircraft fire from the U.S. ships, plus evasive maneuvers, the bombs from the first nine Vals missed Enterprise. However, at 16:44, an armor-piercing, delayed-action bomb penetrated the flight deck near the aft elevator and passed through three decks before detonating below the waterline, killing 35 men and wounding 70 more. Incoming sea water caused Enterprise to develop a slight list, but it was not a major breach of hull integrity.

Just 30 seconds later, the next Val planted its bomb only 15 ft (4.6 m) away from where the first bomb hit. The resulting detonation ignited a large secondary explosion from one of the nearby 5 in (127 mm) guns’ ready powder casings, killing 35 members of the nearby gun crews and starting a large fire.

About a minute later, at 16:46, the third and last bomb hit Enterprise on the flight deck forward of where the first two bombs hit. This bomb exploded on contact, creating a 10 ft (3.0 m) hole in the deck, but caused no further damage. Seven Vals (three from Shokaku, four from Zuikaku) then broke off from the attack on Enterprise to attack the U.S. battleship North Carolina. However, all of their bombs missed and all the Vals involved were shot down by either anti-aircraft fire or U.S. fighters. The attack was over at 16:48, and the surviving Japanese aircraft reassembled in small groups and returned to their ships.

Both sides thought that they had inflicted more damage than was the case. The U.S. claimed to have shot down 70 Japanese aircraft, even though there were only 42 aircraft in all. Actual Japanese losses—from all causes—in the engagement were 25 aircraft, with most of the crews of the lost aircraft not being recovered or rescued. The Japanese, for their part, mistakenly believed that they had heavily damaged two U.S. carriers, instead of just one. The U.S. lost six aircraft in the engagement, with most of the crews being rescued.

Although Enterprise was heavily damaged and on fire, her damage-control teams were able to make sufficient repairs for the ship to resume flight operations at 17:46, only one hour after the engagement ended. At 18:05, the Saratoga strike force returned from sinking Ryūjō and landed without major incident. The second wave of Japanese aircraft approached the U.S. carriers at 18:15 but was unable to locate the U.S. formation because of communication problems and had to return to their carriers without attacking any U.S. ships, losing five aircraft in the process from operational mishaps. Most of the U.S. carrier aircraft launched just before the first wave of Japanese aircraft attacked failed to find any targets. However, two SBD Dauntlesses from Saratoga sighted Kondo’s advanced force and attacked the seaplane tender Chitose, scoring two near-hits which heavily damaged the unarmored ship. The U.S. carrier aircraft either landed at Henderson Field or were able to return to their carriers after dusk. The U.S. ships retired to the south to get out of range of any approaching Japanese warships. In fact, Abe’s “Vanguard” force and Kondō’s “Advance” force were steaming south to try to catch the U.S. carrier task forces in a surface battle, but they turned around at midnight without having made contact with the U.S. warships. Nagumo’s main body, having taken heavy aircraft losses in the engagement and being low on fuel, also retreated northward.

Actions on 25 August

Believing that two U.S. carriers had been taken out of action with heavy damage, Tanaka’s reinforcement convoy again headed toward Guadalcanal, and by 08:00 on 25 August they were within 150 mi (130 nmi; 240 km) of their destination. At this time, Tanaka’s convoy was joined by five destroyers which had shelled Henderson Field the night before, causing slight damage. At 08:05, 18 U.S. aircraft from Henderson Field attacked Tanaka’s convoy, causing heavy damage to Jintsu, killing 24 crewmen, and knocking Tanaka unconscious. The troop transport Kinryu Maru was also hit and eventually sank. Just as the destroyer Mutsuki pulled alongside Kinryu Maru to rescue her crew and embarked troops, she was attacked by four U.S. B-17s from Espiritu Santo which landed five bombs on or around Mutsuki, sinking her immediately. An uninjured but shaken Tanaka transferred to the destroyer Kagerō, sent Jintsu back to Truk, and took the convoy to the Japanese base in the Shortland Islands.

Both the Japanese and the U.S. elected to completely withdraw their warships from the area, ending the battle. The Japanese naval forces lingered near the northern Solomons, out of range of the U.S. aircraft based at Henderson Field, before finally returning to Truk on 5 September.

Aftermath

The battle is generally considered to be a tactical and strategic victory for the U.S. because the Japanese lost more ships, aircraft, and aircrew, and Japanese troop reinforcements for Guadalcanal were delayed. Summing up the significance of the battle, historian Richard B. Frank states:

The Battle of the Eastern Solomons was unquestionably an American victory, but it had little long-term result, apart from a further reduction in the corps of trained Japanese carrier aviators. The (Japanese) reinforcements that could not come by slow transport would soon reach Guadalcanal by other means.

The U.S. lost only seven aircrew members in the battle. However, the Japanese lost 61 veteran aircrew, who were hard for the Japanese to replace because of an institutionalized limited capacity in their naval aircrew training programs and an absence of trained reserves. The troops in Tanaka’s convoy were later loaded onto destroyers at the Shortland Islands and delivered piecemeal, without most of their heavy equipment, to Guadalcanal beginning on 29 August 1942. The Japanese claimed considerably more damage than they had inflicted, including that Hornet—not in the battle—had been sunk, thus avenging its part in the Doolittle Raid.

Emphasizing the strategic value of Henderson Field, in a separate reinforcement effort, Japanese destroyer Asagiri was sunk and two other Japanese destroyers heavily damaged on 28 August, 70 mi (61 nmi; 110 km) north of Guadalcanal in “The Slot” by U.S. aircraft based at the airfield.

Enterprise traveled to Pearl Harbor for extensive repairs, which were completed on 15 October 1942. She returned to the South Pacific on 24 October, just in time for the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and her rematch with Shōkaku and Zuikaku.

|

| The U.S. Navy aircraft carriers USS Wasp (CV-7) (foreground), USS Saratoga (CV-3), and USS Enterprise (CV-6) (background) operating in the Pacific south of Guadalcanal on 12 August 1942. |

|

| Japanese Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo. |

|

| U.S. Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. |

|

| View from a USAAF B-17 bomber of Japanese heavy cruiser Tone, Battle of the Eastern Solomons, 24 August 1942. |

|

| Blasted by U.S. Navy antiaircraft fire, a Japanese plane crashes into the sea off the port bow of the Enterprise. |

|

| The gallery of one of the Enterprise‘s starboard 5-inch guns was heavily damaged by a Japanese bomb during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. |

|

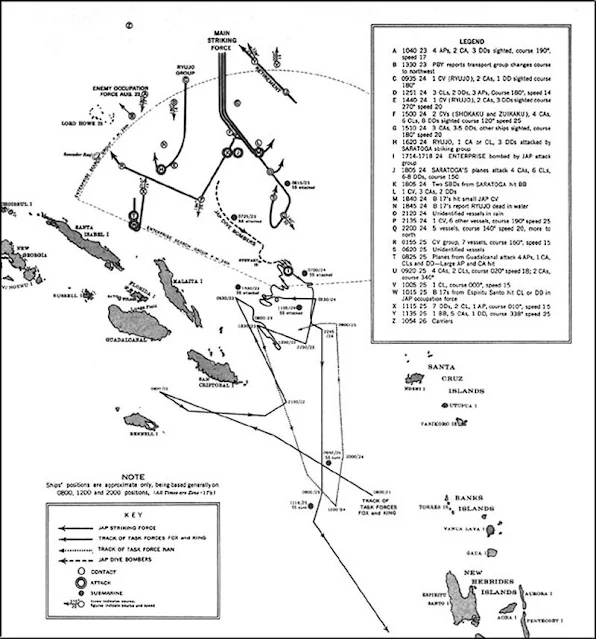

| U.S. Navy map from 1943 of The Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Tracks of Allied (U.S.) forces are most likely fairly accurate. Tracks of Japanese forces are approximate and/or conjectured. |

|

| Japanese track chart during Battle of Eastern Solomons, 23-25 Aug 1942; Annex B of Toyama's 1 November 1945 interrogation. |