|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191. |

The Focke-Wulf Fw 191 was a prototype German bomber of World War II, as the Focke-Wulf firm's entry for the Bomber B advanced medium bomber design competition. Two versions were intended to be produced, a twin-engine version using the Junkers Jumo 222 engine and a four-engine variant which was to have used the smaller Daimler-Benz DB 605 engine. The project was eventually abandoned due to technical difficulties with the engines.

Design and Development

In July 1939, the Reichsluftministerium (RLM) issued a specification for a high-performance medium bomber (the "Bomber B" program). It was to have a maximum speed of 600 km/h (370 mph) and be able to carry a bomb load of 4,000 kg (8,820 lb) to any part of Britain from bases in France or Norway. Furthermore, the new bomber was to have a pressurized crew compartment, of the then-generalized "stepless cockpit" design (with no separate windscreen for the pilot) pioneered by the Heinkel He 111P shortly before the war and used on most German bombers during the war, remotely controlled armament, and was to be powered by two of the new 2,500 PS (2,466 hp, 1,839 kW) class of engines then being developed (Jumo 222 or Daimler-Benz DB 604), with the Jumo 222 being specified for the great majority of such twin-engined designs, that Arado, Dornier, Focke-Wulf and Junkers had created airframe designs to use. The Arado E.340 was eliminated. The Dornier Do 317 was put on a low-priority development contract; and the Junkers Ju 288 and Focke-Wulf Fw 191 were chosen for full development.

Dipl. Ing E. Kösel, who also worked on the Fw 189 reconnaissance aircraft, was supposed to have led the design team for the Fw 191. Overall, the Fw 191 was a clean, all-metal aircraft that featured a shoulder-mounted wing. Two 24-cylinder Jumo 222 engines (which showed more promise than the DB 604 engines) were mounted in nacelles on the wings. An interesting feature was the inclusion of the Multhopp-Klappe, an ingenious form of combined landing flap and dive brake, which was developed by Hans Multhopp. Fuel was carried in five tanks located above the internal bomb bay and two tanks in the wing between the engine nacelles and fuselage.

The tail section was of a twin fins and rudders design, with the tailplane having a small amount of dihedral. The main landing gear legs retracted to the rear and rotated 90° to lie flat in each engine nacelle with the mainwheels resting atop the lower ends of the gear struts when fully retracted, much like the main gear on the production versions of the Ju 88 already did. Also, the tailwheel retracted forwards into the fuselage. A crew of four sat in the pressurized cockpit, and a large Plexiglas dome was provided for the navigator; the radio operator could also use this dome to aim the remotely controlled rear guns.

The Fw 191 followed established Luftwaffe practice in concentrating the crew in the nose compartment, also including the nearly ubiquitous Bola, inverted-casemate undernose gondola for defensive weapons mounts first used on the Junkers Ju 88A before the war, and in the use of a "stepless cockpit", having no separate windscreen for the pilot, as the later -P and -H versions of the Heinkel He 111 already did. This was pressurized for high-altitude operations. The proposed operational armament consisted of one 20 mm MG 151 cannon in a chin turret, twin 20 mm MG 151 in a remotely controlled dorsal turret, twin 20 mm MG 151 in a remotely controlled ventral turret, a tail turret with one or two machine guns and remotely controlled weapons in the rear of the engine nacelles. However, different combinations were mounted in the prototype aircraft. Sighting stations were provided above the crew compartment, and either end of the Bola beneath the nose.

The aircraft had an internal bomb bay. In addition, bombs or torpedoes could be carried on external racks between the fuselage and the engine nacelles. The design was to have had a maximum speed of 600 km/h (370 mph), a bomb load of 4,000 kg (8,820 lb), and a range allowing it to bomb any target in Britain from bases in France and Norway.

Failure and End of Program

It is said that the intention to use electric power for almost all of the aircraft's auxiliary systems (as used on the Fw 190 fighter), requiring the installation of a large number of electric motors and wiring led to a nickname for the Fw 191 of "Das fliegende Kraftwerk" ("the flying powerstation"). This also had the detrimental effect of adding even more weight to the overburdened airframe, plus there was also the danger of a single enemy bullet putting every system out of action if the generator was hit. Dipl. Ing Melhorn took the Fw 191 V1 on its maiden flight early in 1942, with immediate problems arising from the lower rated engines not providing enough power, as was anticipated. The Multhopp-Klappe, gave severe flutter problems when extended, and indicated a need for a redesign. At this point, only dummy gun installations were fitted and no bomb load was carried. After completing ten test flights, the Fw 191 V1 was joined by the similar V2, but only a total of ten hours of test flight time was logged. The 2,500 PS (2,466 hp, 1,839 kW) Junkers Jumo 222 engines which would have powered the Fw 191 proved troublesome. In total only three prototype aircraft, V1, V2 and V6, were built. The project was crippled by engine problems and an extensive use of electrical motor-driven systems. Problems arose almost immediately when the Jumo 222 engines were not ready in time for the first flight tests, so a pair of 1,560 PS (1,539 hp, 1,147 kW) BMW 801A radial engines were fitted. This made the Fw 191 V1 seriously underpowered. Another problem arose with the RLM's insistence that all systems that would normally be hydraulic or mechanically activated should be operated by electric motors.

At this point, the RLM allowed the redesign and removal of the electric motors (to be replaced by the standard hydraulics), so the Fw 191 V3, V4 and V5 were abandoned. The Fw 191 V6 was then modified to the new design, and also a pair of specially prepared Jumo 222 engines were fitted that developed 2,200 PS (2,170 hp, 1,618 kW) for takeoff. The first flight of the new Fw 191 took place in December 1942 with Flugkapitän Hans Sander at the controls. Although the V6 flew better, the Jumo 222 were still not producing their design power, and the whole Jumo 222 development prospect was considered dubious due to the shortage of special metals for it. The Fw 191 V6 was to have been the production prototype for the Fw 191A series.

Due to the German aviation engine industry having chronic problems in producing engines capable of equal to or more than the 1,500 kW (2,000 PS) figure during the war, that were fit for service, the Jumo 222 engines were having a lot of teething problems and the Daimler Benz DB 604 had already been abandoned, a new proposal was put forth for the Fw 191B series. The V7 through V12 machines were abandoned in favor of installing a pair of Daimler Benz DB 606 or 610 "power system" engines (basically coupled pairs of either DB 601 or 605 12-cylinder engines) in the Fw 191 V13. Their lower power-to-weight ratio (each "power system" weighed 1.5 tonnes) meant that the armament and payload would have to be reduced. It had already been decided to delete the engine nacelle gun turrets, and to make the rest manually operated. Five more prototypes were planned with the new engine arrangement, V14 through V18, but none were ever built, possibly from the August 1942 condemnation by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring of the coupled "power system" DB 606 and 610 powerplants as "welded-together engines", in regards to their being the primary cause of the unending series of powerplant problems in their primary use, as the engines on Heinkel's Heinkel 177A Greif, Germany's only heavy bomber to reach production in World War II.

One final attempt was made to save the Fw 191 program; the Fw 191C was proposed as a four engined aircraft, using either the 1,340 PS (1,322 hp, 986 kW) Junkers Jumo 211F, the 1,350 PS (1,332 hp, 993 kW) DB 601E, the 1,475 PS (1,455 hp, 1,085 kW) DB 605A or similar rated DB 628 engines. Also, the cabin would be unpressurized and the guns manually operated, with a rear step in the bottom of the deepened fuselage — in the manner of the near-ubiquitous Bola gondola used by the majority of German bombers for ventral defense under the nose — being provided for the gunner. Focke-Wulf used the designations Fw 391 and Fw 491 for the different variants of the Fw 191C, but these were unofficial and never allocated by the RLM.

The "Bomber B" program had been canceled, due mainly to no engines of the 2,500 PS class being available, which was one of the primary requirements in the "Bomber B" program. Although the Fw 191 will be remembered as a failure, the airframe and design eventually proved themselves to be sound; only the underpowered engines and insistence on electric motors to operate all the systems doomed the aircraft. There were only three Fw 191s built (V1, V2 and V6), and no examples of the Fw 191B or C ever advanced past the design stage. The RLM kept in reserve for Focke-Wulf the designation Fw 391 for follow-up designs but nothing came of it and the project was eventually scrapped.

Type: Advanced Medium Bomber

Bomber B design competitor

National origin: Germany

Manufacturer: Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau

Status: Prototype

Primary user: Luftwaffe (cancelled order)

Number built: 3

First flight: Early 1942

Specifications (Fw 191B - DB 610 Engines)

Crew: 5

Length: 19.63 m (64 ft 5 in)

Wingspan: 26 m (85 ft 4 in)

Height: 5.6 m (18 ft 4 in)

Wing area: 70.5 m2 (759 sq ft)

Gross weight: 25,490 kg (56,196 lb)

Maximum takeoff weight: 25,319 kg (55,819 lb)

Fuel capacity: 3,930 L (1,040 US gal; 860 imp gal) normal ; 7,570 L (2,000 US gal; 1,670 imp gal) with ferry tanks

Powerplant: 2 × Daimler-Benz DB 610A and B 24-cylinder liquid-cooled coupled V-12 piston engine, 2,140 kW (2,870 hp) each for take-off at 2,800 rpm at sea level

Propellers: 4-bladed VDM constant-speed propeller, 4.52 m (14 ft 10 in) diameter LH and RH rotation

Maximum speed: 565 km/h (351 mph, 305 kn) at 3,950 m (12,960 ft)

Cruise speed: 500 km/h (310 mph, 270 kn)

Range: 1,800 km (1,100 mi, 970 nmi) at 500 km/h (310 mph; 270 kn)

Ferry range: 3,860 km (2,400 mi, 2,080 nmi) at 490 km/h (300 mph; 260 kn)

Service ceiling: 8,780 m (28,800 ft) at 23,135 kg (51,004 lb)

Rate of climb: 7.67 m/s (1,500 ft/min) at 23,860 kg (52,600 lb)

Guns:

2 × 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 81 machine guns in chin turret

2 × 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 81 machine guns in remote-controlled turret at rear of each engine nacelle

1 × 20 mm (0.79 in) MG 151/20 cannon and 2 × 13 mm (.51 in) MG 131 machine guns in dorsal turret

1 × 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon and 2 × 13 mm (.51 in) MG 131 machine guns in ventral turret

Bombs: 4,200 kg (9,240 lb) of bombs (Two torpedoes could also be carried internally)

Bibliography

Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1945, page 117c and addendum 23

Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London. Studio Editions Ltd, 1989.

Munson, Kenneth (1978). German Aircraft Of World War 2 in colour. Poole, Dorsett, UK: Blandford Press.

Herwig, Dieter; Rode, Heinz (2000). Luftwaffe secret projects : strategic bombers 1935-45 (1st English ed.). Earl Shilton: Midland. p 29.

Green, William (2010). Aircraft of the Third Reich : Volume one. London: Aerospace Publishing Limited. pp. 463–465.

|

| Focke-Wulf 191V-1. (Nowarra/Ray Wagner/SDASM Archives) |

|

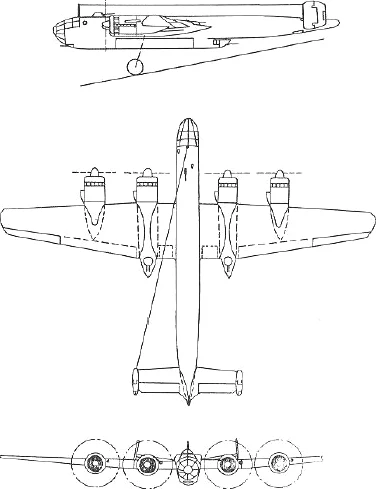

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191A. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191B with DB 610. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191C. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1 with BMW 801MA radial engines. Note crew access ladder and open bomb bay doors. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1. |

|

| Close up of rear firing guns on the Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1 . |

|

| Detail of the Multhopp-Klappe, a combination landing flap and dive brake. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 V1. |

|

| Original Focke-Wulf Fw 191 factory drawing showing the bomb loading table. |

|

| Original Focke-Wulf factory drawing showing the various bomb loads that the Focke-Wulf Fw 191 could carry. |

|

| (from Geheimprojekte der Luftwaffe Band II: Strategische Bomber 1935-1945) |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 cockpit. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191. |

|

| Top: Focke-Wulf Fw 191B. Bottom: Focke-Wulf Fw 191C. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191C. |

|

| Artist illustration of Focke-Wulf Fw 191. |

|

| Top: Focke-Wulf Fw 191. Bottom: Focke-Wulf Fw 191C. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191A. |

|

| Pilot's station looking towards rear of aircraft. |

|

| View of cockpit looking forward from behind pilot's seat. |

|

| DB 604 engine. |

|

| Jumo 222 engine. |

|

| Focke-Wulf Fw 191 factory model. |

.png)

.png)