The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, fought during 25–27 October 1942, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Santa Cruz or in Japan as the Battle of the South Pacific, was the fourth carrier battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II. It was also the fourth major naval engagement fought between the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy during the lengthy and strategically important Guadalcanal campaign. As in the battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and the Eastern Solomons, the ships of the two adversaries were rarely in sight or gun range of each other. Instead, almost all attacks by both sides were mounted by carrier- or land-based aircraft.

In an attempt to drive Allied forces from Guadalcanal and nearby islands and end the stalemate that had existed since September 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army planned a major ground offensive on Guadalcanal for 20–25 October 1942. In support of this offensive, and with the hope of engaging Allied naval forces, Japanese carriers and other large warships moved into a position near the southern Solomon Islands. From this location, the Japanese naval forces hoped to engage and decisively defeat any Allied (primarily U.S.) naval forces, especially carrier forces, that responded to the ground offensive. Allied naval forces also hoped to meet the Japanese naval forces in battle, with the same objectives of breaking the stalemate and decisively defeating their adversary.

The Japanese ground offensive on Guadalcanal was under way in the Battle for Henderson Field while the naval warships and aircraft from the two adversaries confronted each other on the morning of 26 October 1942, just north of the Santa Cruz Islands. After an exchange of carrier air attacks, Allied surface ships retreated from the battle area with one carrier sunk (Hornet) and another heavily damaged (Enterprise). The participating Japanese carrier forces also retired because of high aircraft and aircrew losses, plus significant damage to two carriers.

Although Santa Cruz was a tactical victory and a short-term strategic victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk and damaged, and control of the seas around Guadalcanal, Japan’s loss of many irreplaceable veteran aircrews proved to be a long-term strategic advantage for the Allies, whose aircrew losses in the battle were relatively low and quickly replaced.

Background

On 7 August 1942, Allied forces (primarily U.S.) landed on Japanese-occupied Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and to secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of neutralizing the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.

After the Battle of the Eastern Solomons on 24–25 August, in which the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise was heavily damaged and forced to travel to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, for a month of major repairs, three U.S. carrier task forces remained in the South Pacific area. The task forces included the carriers USS Wasp, Saratoga, and Hornet plus their respective air groups and supporting surface warships, including battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, and were primarily stationed between the Solomons and New Hebrides (Vanuatu) islands. At this location, the carriers were charged with guarding the line of communication between the major Allied bases at New Caledonia and Espiritu Santo, supporting the Allied ground forces at Guadalcanal and Tulagi against any Japanese counteroffensives, covering the movement of supply ships to Guadalcanal, and engaging and destroying any Japanese warships, especially carriers, that came within range.

The area of ocean in which the U.S. carrier task forces operated was known as “Torpedo Junction” by U.S. forces because of the high concentration of Japanese submarines in the area.

On 31 August, USS Saratoga was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-26 and was out of action for three months for repairs. On 14 September, USS Wasp was hit by three torpedoes fired by Japanese submarine I-19 while supporting a major reinforcement and resupply convoy to Guadalcanal and almost engaging two Japanese carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku (which withdrew just before the two adversaries came into range of each other’s aircraft). With power knocked out from torpedo damage, Wasp’s damage-control teams were unable to contain the ensuing large fires, and she was abandoned and scuttled.

Although the U.S. now had only one operational carrier (Hornet) in the South Pacific, the Allies still maintained air superiority over the southern Solomon Islands because of their aircraft based at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. However, at night, when aircraft were not able to operate effectively, the Japanese were able to operate their ships around Guadalcanal almost at will. Thus, a stalemate in the battle for Guadalcanal developed, with the Allies delivering supplies and reinforcements to Guadalcanal during the day, and the Japanese doing the same by warship (called the “Tokyo Express” by the Allies) at night, with neither side able to deliver enough troops to the island to secure a decisive advantage. By mid-October, both sides had roughly an equal number of troops on the island. The stalemate was briefly interrupted by two large-ship naval actions. On the night of 11–12 October, a U.S. naval force intercepted and defeated a Japanese naval force en route to bombard Henderson Field in the Battle of Cape Esperance. But just two nights later, a Japanese force that included the battleships Haruna and Kongō successfully bombarded Henderson Field, destroying most of the U.S. aircraft and inflicting severe damage on the field’s facilities. Although still marginally operational, it took several weeks for the airfield to recover from the damage and replace the destroyed aircraft.

The U.S. made two moves to try to break the stalemate in the battle for Guadalcanal. First, repairs to Enterprise were expedited so that she could return to the South Pacific as soon as possible. On 10 October, Enterprise received her new air group (Air Group 10) and on 16 October, she left Pearl Harbor; and on 23 October, she arrived back in the South Pacific and rendezvoused with Hornet and the rest of the Allied South Pacific naval forces on 24 October, 273 nmi (506 km; 314 mi) northeast of Espiritu Santo.

Second, on 18 October, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Allied Commander-in-Chief of Pacific Forces, replaced Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley with Vice Admiral William Halsey, Jr. as Commander, South Pacific Area: this position commanded Allied forces involved in the Solomon Islands campaign. Nimitz felt that Ghormley had become too myopic and pessimistic to lead Allied forces effectively in the struggle for Guadalcanal. Halsey was reportedly respected throughout the U.S. naval fleet as a “fighter.” Upon assuming command, Halsey immediately began making plans to draw the Japanese naval forces into a battle, writing to Nimitz, “I had to begin throwing punches almost immediately.”

The Japanese Combined Fleet was also seeking to draw Allied naval forces into what was hoped to be a decisive battle. Two fleet carriers—Hiyō and Jun’yō—and one light carrier—Zuihō—arrived at the main Japanese naval base at Truk Atoll from Japan in early October and joined Shōkaku and Zuikaku. With five carriers fully equipped with air groups, plus their numerous battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, the Japanese Combined Fleet, directed by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, was confident that it could make up for the defeat at the Battle of Midway. Apart from a couple of air raids on Henderson Field in October, the Japanese carriers and their supporting warships stayed in the northwestern area of the Solomon Islands, out of the battle for Guadalcanal and waiting for a chance to approach and engage the U.S. carriers. With the Japanese Army’s next planned major ground attack on Allied forces on Guadalcanal set for 20 October, Yamamoto’s warships began to move towards the southern Solomons to support the offensive and to be ready to engage any Allied (primarily U.S.) ships, especially carriers, that approached to support the Allied defenses on Guadalcanal.

Prelude

From 20–25 October, Japanese land forces on Guadalcanal attempted to capture Henderson Field with a large-scale attack against U.S. troops defending the airfield. The attack was decisively defeated with heavy casualties for the Japanese during the Battle for Henderson Field.

Incorrectly believing that the Japanese army troops had succeeded in capturing Henderson Field, the Japanese sent warships toward Guadalcanal on the morning of 25 October to support their ground forces on the island. Aircraft from Henderson Field attacked the convoy throughout the day, sinking the light cruiser Yura and damaging the destroyer Akizuki.

Despite the failure of the Japanese ground offensive and the loss of Yura, the rest of the Combined Fleet continued to maneuver near the southern Solomon Islands on 25 October with the hope of encountering Allied naval forces in battle. The Japanese naval forces now comprised four carriers, because Hiyō had suffered an accidental, damaging fire in her engine room on 22 October that forced her to return to Truk for repairs.

The Japanese naval forces were divided into three groups: The “Advanced” force consisted of the carrier Jun’yō, plus two battleships, four heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and 10 destroyers, and was commanded by Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondō in heavy cruiser Atago; the “Main Body” consisted of Shōkaku, Zuikaku, and Zuihō plus one heavy cruiser and eight destroyers, and was commanded by Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo aboard Shōkaku; and the “Vanguard” force contained two battleships, three heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and seven destroyers, and was commanded by Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe in battleship Hiei. In addition to commanding the Advanced force, Kondo acted as the overall commander of the three forces.

On the U.S. side, the Hornet and Enterprise task groups, under the overall command of Rear Admiral Thomas Kinkaid swept around to the north of the Santa Cruz Islands on 25 October searching for the Japanese naval forces. The U.S. warships were deployed as two separate carrier groups, each centered on either Hornet or Enterprise, and separated from each other by about 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi). A U.S. PBY Catalina based in the Santa Cruz Islands located the Japanese Main body carriers at 11:03. However, the Japanese carriers were about 355 nmi (657 km; 409 mi) from the U.S. force, just beyond carrier aircraft range. Kinkaid, hoping to close the range to be able to execute an attack that day, steamed towards the Japanese carriers at top speed and, at 14:25, launched a strike force of 23 aircraft. But the Japanese, knowing that they had been spotted by U.S. aircraft and not knowing where the U.S. carriers were, turned to the north to stay out of range of the U.S. carriers’ aircraft. Thus, the U.S. strike force returned to their carriers without finding or attacking the Japanese warships.

Battle

Carrier Action on 26 October: First Strikes

At 02:50 on 26 October, the Japanese naval forces reversed direction and the naval forces of the two adversaries closed the distance until they were only 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) away from each other by 05:00. Both sides launched search aircraft and prepared their remaining aircraft to attack as soon as the other side’s ships were located. Although a radar-equipped PBY Catalina sighted the Japanese carriers at 03:10, the report did not reach Kinkaid until 05:12. Therefore, believing that the Japanese ships had probably changed position during the intervening two hours, he decided to withhold launching a strike force until he received more current information on the location of the Japanese ships.

At 06:45, a U.S. scout aircraft sighted the carriers of Nagumo’s main body. At 06:58, a Japanese scout aircraft reported the location of Hornet’s task force. Both sides raced to be the first to attack the other. The Japanese were first to get their strike force launched, with 64 aircraft, including 21 Aichi D3A2 dive bombers, 20 Nakajima B5N2 torpedo bombers, 21 A6M3 Zero fighters, and two Nakajima B5N2 command and control aircraft on the way towards Hornet by 07:40. Also at 07:40, two U.S. SBD-3 Dauntless scout aircraft, responding to the earlier sighting of the Japanese carriers, arrived and dove on Zuihō. With the Japanese combat air patrol (CAP) busy chasing other U.S. scout aircraft away, the two U.S. aircraft were able to hit Zuihō with both their 500-pound bombs, causing heavy damage and preventing the carrier’s flight deck from being able to land aircraft.

Meanwhile, Kondo ordered Abe’s Vanguard force to race ahead to try to intercept and engage the U.S. warships. Kondo also brought his own Advanced force forward at maximum speed so that Junyō’s aircraft could join in the attacks on the U.S. ships. At 08:10, Shōkaku launched a second wave of strike aircraft, consisting of 19 dive bombers and eight Zeros, and Zuikaku launched 16 torpedo bombers at 08:40. Thus, by 09:10 the Japanese had 110 aircraft on the way to attack the U.S. carriers.

The U.S. strike aircraft were running about 20 minutes behind the Japanese. Believing that a speedy attack was more important than a massed attack, and because they lacked fuel to spend time assembling prior to the strike, the U.S. aircraft proceeded in small groups towards the Japanese ships, rather than forming into a single large strike force. The first group—consisting of 15 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, six Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bombers, and eight Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters, led by Lieutenant Commander William J. “Gus” Widhelm from Hornet—was on its way by about 08:00. A second group—consisting of three SBDs, nine TBFs (including the Air Group Commander’s), and eight Wildcats from Enterprise—was off by 08:10. A third group—which included nine SBDs, ten TBFs (including the Air Group Commander’s), and seven F4Fs from Hornet—was on its way by 08:20.

At 08:40, the opposing aircraft strike formations passed within sight of each other. Nine Zeros from Zuihō surprised and attacked the Enterprise group, attacking the climbing aircraft from out of the sun. In the resulting engagement, four Zeros, three Wildcats, and two TBFs were shot down, with another two TBFs and a Wildcat forced by heavy damage to return to Enterprise.

At 08:50, the lead U.S. attack formation from Hornet spotted four ships from Abe’s Vanguard force. Pressing on, the U.S. aircraft sighted the Japanese carriers and prepared to attack. Three Zeros from Zuihō attacked the formation’s Wildcats, drawing them away from the bombers they were assigned to protect. Thus, the dive bombers in the first group initiated their attacks without fighter escort. Twelve Zeros from the Japanese carrier CAP attacked the SBD formation, shot down two (including Widhelm’s, although he survived), and forced two more to abort. The remaining 11 SBDs commenced their attack dives on Shōkaku at 09:27, hitting her with three to six bombs, wrecking her flight deck and causing serious damage to the interior of the ship. The final SBD of the 11 lost track of Shōkaku and instead dropped its bomb near the Japanese destroyer Teruzuki, causing minor damage. The six TBFs in the first strike force, having become separated from their strike group, did not find the Japanese carriers and eventually turned back towards Hornet. On the way back, they attacked the Japanese heavy cruiser Tone, missing with all their torpedoes.

The TBFs of the second U.S. attack formation from Enterprise were unable to locate the Japanese carriers and instead attacked the Japanese heavy cruiser Suzuya from Abe’s Vanguard force but caused no damage. At about the same time, nine SBDs from the third U.S. attack formation — from Hornet — found Abe’s ships and attacked the Japanese heavy cruiser Chikuma, hitting her with two 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs and causing heavy damage. The three Enterprise SBDs then arrived and also attacked Chikuma, causing more damage with one bomb hit and two near-misses. Finally, the nine TBFs from the third strike group arrived and attacked the smoking Chikuma, scoring one more hit. Chikuma, escorted by two destroyers, withdrew from the battle and headed towards Truk for repairs.

The U.S. carrier forces received word from their outbound strike aircraft at 08:30 that Japanese attack aircraft were headed their way. At 08:52, the Japanese strike force commander sighted the Hornet task force (the Enterprise task force was hidden by a rain squall) and deployed his aircraft for attack. At 08:55, the U.S. carriers detected the approaching Japanese aircraft on radar—about 35 nmi (65 km; 40 mi) away—and began to vector the 37 Wildcats of their CAP to engage the incoming Japanese aircraft. However, communication problems, mistakes by the U.S. fighter control directors, and primitive control procedures prevented all but a few of the U.S. fighters from engaging the Japanese aircraft before they began their attacks on Hornet. Although the U.S. CAP was able to shoot down several dive bombers, most of the Japanese aircraft commenced their attacks relatively unmolested by U.S. fighters.

At 09:09, the anti-aircraft guns of Hornet and her escorting warships opened fire as the 20 untouched Japanese torpedo planes and remaining 16 dive bombers commenced their attacks on the carrier. At 09:12, a dive bomber placed its 551 lb (250 kg), semi-armor-piercing bomb dead center on Hornet’s flight deck, across from the island, which penetrated three decks before exploding, killing 60 men. Moments later, a 534 lb (242 kg) “land” bomb struck the flight deck, detonating on impact to create an 11 ft (3.4 m) hole and kill 30 men. A minute or so later, a third bomb hit Hornet near where the first bomb hit, penetrating three decks before exploding, causing severe damage but no loss of life. At 09:14, a dive bomber was set on fire by Hornet’s anti-aircraft guns; the pilot deliberately crashed into Hornet’s stack, killing seven men and spreading burning aviation fuel over the signal deck.

At the same time as the dive bombers were attacking, the 20 torpedo bombers were also approaching Hornet from two different directions. Despite suffering heavy losses from anti-aircraft fire, the torpedo planes planted two torpedoes into Hornet’s side between 09:13 and 09:17, knocking out her engines. As Hornet came to a stop, a damaged Japanese dive bomber approached and purposely crashed into the carrier’s side, starting a fire near the ship’s main supply of aviation fuel. At 09:20, the surviving Japanese aircraft departed, leaving Hornet dead in the water and burning. Twenty-five Japanese and six American aircraft were destroyed in this attack.

With the assistance of fire hoses from three escorting destroyers, the fires on Hornet were under control by 10:00. Wounded personnel were evacuated from the carrier, and an attempt was made by the heavy cruiser USS Northampton to tow Hornet away from the battle area. However, the effort to rig the towline took some time, and more attack waves of Japanese aircraft were inbound.

Carrier Action on 26 October: Post-First Strike Actions

Starting at 09:30, Enterprise landed many of the damaged and fuel-depleted CAP fighters and returning scout aircraft from both carriers. However, with her flight deck full, and the second wave of incoming Japanese aircraft detected on radar at 09:30, Enterprise ceased landing operations at 10:00. Fuel-depleted aircraft then began ditching in the ocean, and the carrier’s escorting destroyers rescued the aircrews. One of the ditching aircraft, a damaged TBF from Enterprise’s strike force that had been attacked earlier by Zuihō Zeros, crashed into the water near the destroyer USS Porter. As Porter rescued the TBF’s aircrew, she was struck by a torpedo, perhaps from the ditched aircraft, causing heavy damage and killing 15 crewmen. After the task force commander ordered the destroyer scuttled, the crew was rescued by the destroyer USS Shaw which then sank Porter with gunfire.

As the first wave of Japanese strike aircraft began returning to their carriers from their attack on Hornet, one of them spotted the Enterprise task force (which had just emerged from a rain squall) and reported the carrier’s position. The second Japanese aircraft strike wave, believing Hornet to be sinking, directed their attacks on the Enterprise task force, beginning at 10:08. Again, the U.S. CAP had trouble intercepting the Japanese aircraft before they attacked Enterprise, shooting down only two of the 19 dive bombers as they began their dives on the carrier. Attacking through the intense anti-aircraft fire put up by Enterprise and her escorting warships, the bombers hit the carrier with two 551 lb (250 kg) bombs and near-missed with another. The bombs killed 44 men and wounded 75, and caused heavy damage to the carrier, including jamming her forward elevator in the “up” position. Twelve of the nineteen Japanese bombers were lost in this attack.

Twenty minutes later, the 16 Zuikaku torpedo planes arrived and split up to attack Enterprise. One group of torpedo bombers was attacked by two CAP Wildcats which shot down three of them and damaged a fourth. On fire, the fourth damaged aircraft purposely crashed into the destroyer Smith, setting the ship on fire and killing 57 of her crew. The torpedo carried by this aircraft detonated shortly after impact, causing more damage. The fires initially seemed out of control until Smith’s commanding officer ordered the destroyer to steer into the large spraying wake of the battleship USS South Dakota, which helped put out the fires. Smith then resumed her station, firing her remaining anti-aircraft guns at the torpedo planes.

The remaining torpedo planes attacked Enterprise, South Dakota, and cruiser Portland, but all of their torpedoes missed or failed, causing no damage. The engagement was over at 10:53; nine of the 16 torpedo aircraft were lost in this attack. After suppressing most of the onboard fires, at 11:15 Enterprise reopened her flight deck to begin landing returning aircraft from the morning U.S. strikes on the Japanese warship forces. However, only a few aircraft landed before the next wave of Japanese strike aircraft arrived and began their attacks on Enterprise, forcing a suspension of landing operations.

Between 09:05 and 09:14, Jun’yō had arrived within 280 nmi (320 mi; 520 km) of the U.S. carriers and launched a strike of 17 dive bombers and 12 Zeros. As the Japanese main body and advanced force maneuvered to try to join formations, Jun’yō readied follow-up strikes. At 11:21, the Jun’yō aircraft arrived and dove on the Enterprise task force. The dive bombers scored one near miss on Enterprise, causing more damage, and one hit each on South Dakota and light cruiser San Juan, causing moderate damage to both ships. Eleven of the 17 Japanese dive bombers were destroyed in this attack.

At 11:35, Kinkaid decided to withdraw Enterprise and her screening ships from battle, since Hornet was out of action, Enterprise was heavily damaged, and surmising, correctly, that the Japanese had one or two undamaged carriers in the area. Leaving Hornet behind, Kinkaid directed the carrier and her task force to retreat as soon as they were able. Between 11:39 and 13:22, Enterprise recovered 57 of the 73 airborne U.S. aircraft as she retreated. The remaining U.S. aircraft ditched in the ocean, and their aircrews were rescued by escorting warships.

Between 11:40 and 14:00, the two undamaged Japanese carriers, Zuikaku and Jun’yō, recovered the few aircraft that returned from the morning strikes on Hornet and Enterprise and prepared follow-up strikes. It was now that the devastating losses sustained during these attacks became apparent. Lt. Cmdr. Okumiya Masatake, Jun’yō’s air staff officer, described the return of the carrier’s first strike groups:

We searched the sky with apprehension. There were only a few planes in the air in comparison with the numbers launched several hours before... The planes lurched and staggered onto the deck, every single fighter and bomber bullet holed ... As the pilots climbed wearily from their cramped cockpits, they told of unbelievable opposition, of skies choked with antiaircraft shell bursts and tracers.

Only one of Jun’yō’s bomber leaders returned from the first strike, and upon landing he appeared “so shaken that at times he could not speak coherently.”

At 13:00, Kondo’s Advanced force and Abe’s Vanguard force warships together headed directly towards the last reported position of the U.S. carrier task forces and increased speed to try to intercept them for a warship gunfire battle. The damaged carriers Zuihō and Shōkaku, with Nagumo still on board, retreated from the battle area, leaving Rear Admiral Kakuji Kakuta in charge of the Zuikaku and Jun’yō aircraft forces. At 13:06, Junyō launched her second strike of seven torpedo planes and eight Zeros, and Zuikaku launched her third strike of seven torpedo planes, two dive bombers, and five Zeros. At 15:35, Junyō launched the last Japanese strike force of the day, consisting of four bombers and six Zeros.

After several technical problems, Northampton finally began slowly towing Hornet out of the battle area at 14:45, at a speed of only five knots. Hornet’s crew was on the verge of restoring partial power but at 15:20, Jun’yō’s second strike arrived, and the seven torpedo planes attacked the almost stationary carrier. Although six of the torpedo planes missed, at 15:23, one torpedo struck Hornet mid-ship, which proved to be the fatal blow. The torpedo hit destroyed the repairs to the power system and caused heavy flooding and a 14° list. With no power to pump out the water, Hornet was given up for lost, and the crew abandoned ship. The third strike from Zuikaku attacked Hornet during this time, hitting the sinking ship with one more bomb. All of Hornet’s crewmen were off by 16:27. The last Japanese strike of the day dropped one more bomb on the sinking carrier at 17:20.

After being informed that Japanese forces were approaching and that further towing efforts were infeasible, Admiral Halsey ordered the Hornet sunk. While the rest of the U.S. warships retired towards the southeast to get out of range of Kondō’s and Abe’s oncoming fleet, destroyers USS Mustin and Anderson attempted to scuttle Hornet with multiple torpedoes and over 400 shells, but she still remained afloat. With advancing Japanese naval forces only 20 minutes away, the two U.S. destroyers abandoned Hornet’s burning hulk at 20:40. By 22:20, the rest of Kondō’s and Abe’s warships had arrived at Hornet’s location. The destroyers Makigumo and Akigumo then finished Hornet with four 24 in (610 mm) torpedoes. At 01:35 on 27 October 1942, she finally sank. Several night attacks by radar-equipped Catalinas on Jun’yō and Teruzuki, knowledge of the head start the U.S. warships had in their retreat from the area, plus a critical fuel situation apparently caused the Japanese to reconsider further pursuit of the U.S. warships. After refueling near the northern Solomon Islands, the ships returned to their main base at Truk on 30 October. During the U.S. withdrawal from the battle area towards Espiritu Santo and New Caledonia, while taking evasive action from a Japanese submarine, South Dakota collided with destroyer Mahan, heavily damaging the destroyer.

Aftermath

Both sides claimed victory. The Americans stated that two Shōkaku-class fleet carriers had been hit with bombs and eliminated. Kinkaid’s summary of damage to the Japanese included hits to a battleship, three heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, and possible hits on another heavy cruiser. For their part, the Japanese asserted that they sank three American carriers, one battleship, one cruiser, one destroyer, and one “unidentified large warship.” Actual American losses comprised the carrier Hornet and the destroyer Porter, and damage to Enterprise, the light cruiser San Juan, the destroyer Smith and the battleship South Dakota.

The loss of Hornet was a severe blow for Allied forces in the South Pacific, leaving Enterprise as the one operational, but damaged, Allied carrier in the entire Pacific theater. As she retreated from the battle, the crew posted a sign on the flight deck: “Enterprise vs Japan.” Enterprise received temporary repairs at New Caledonia and, although not fully restored, returned to the southern Solomons area just two weeks later to support Allied forces during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. There she played an important role in what turned out to be the decisive naval engagement in the overall campaign for Guadalcanal, when her aircraft sank several Japanese warships and troop transports during the naval skirmishes around Henderson Field. The lack of carriers pressed the Americans and Japanese to deploy battleships in night operations around Guadalcanal, one of only two actions in the entire Pacific War in which battleships fought each other, with South Dakota again being damaged while two Japanese battleships were lost.

Although the Battle of Santa Cruz was a tactical victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk, it came at a high cost for their naval forces, as Jun’yō was the only active aircraft carrier left to challenge Enterprise or Henderson Field for the remainder of the Guadalcanal campaign. Zuikaku, despite being undamaged and having recovered the aircraft from the two damaged carriers, returned to home islands via Truk for training and aircraft ferrying duties, only returning to the South Pacific in February 1943 to cover the evacuation of Japanese ground forces from Guadalcanal. Both damaged carriers were forced to return to Japan for extensive repairs and refitting. After repair, Zuihō returned to Truk in late January 1943. Shōkaku was under repair until March 1943 and did not return to the front until July 1943, when she was reunited with Zuikaku at Truk.

The most significant losses for the Japanese Navy were in aircrew. The U.S. lost 81 aircraft of the 175 U.S. aircraft at the start of the battle, of which 33 were fighters, 28 were dive-bombers, and 20 were torpedo bombers. Only 26 pilots and aircrew members were lost. The Japanese fared much worse, especially in airmen; in addition to losing 99 aircraft of the 203 involved in the battle, they lost 148 pilots and aircrew members including two dive bomber group leaders, three torpedo squadron leaders, and eighteen other section or flight leaders. Forty-nine percent of the Japanese torpedo bomber aircrews involved in the battle were killed along with 39% of the dive bomber crews and 20% of the fighter pilots. The Japanese lost more aircrew at Santa Cruz than they had lost in each of the three previous carrier battles at Coral Sea (90), Midway (110), and Eastern Solomons (61). By the end of the Santa Cruz battle, at least 409 of the 765 elite Japanese carrier aviators who had participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor were dead. Having lost so many of its veteran carrier aircrew, and with no quick way to replace them – because of an institutionalized limited capacity in its naval aircrew training programs and an absence of trained reserves – the undamaged Zuikaku and Hiyō were also forced to return to Japan because of the scarcity of trained aircrew to man their air groups. Although the Japanese carriers returned to Truk by the summer of 1943, they played no further offensive role in the Solomon Islands campaign.

Admiral Nagumo was relieved of command shortly after the battle and reassigned to shore duty in Japan. He acknowledged that the victory was incomplete:

[T]his battle was a tactical win, but a shattering strategic loss for Japan ... Considering the great superiority of our enemy’s industrial capacity, we must win every battle overwhelmingly in order to win this war. This last one, although a victory, unfortunately, was not an overwhelming victory.

In retrospect, despite being a tactical victory, the battle effectively ended any hope the Japanese navy might have had of scoring a decisive victory before the industrial might of the United States placed that goal out of reach. Historian Eric Hammel summed up the significance of the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands as, “Santa Cruz was a Japanese victory. That victory cost Japan her last best hope to win the war.”

Military historian Dr. John Prados offers a dissenting view, asserting that this was not a Pyrrhic victory for Japan, but a strategic victory:

By any reasonable measure the Battle of Santa Cruz marked a Japanese victory – and a strategic one. At its end the Imperial Navy possessed the only operational carrier force in the Pacific. The Japanese had sunk more ships and more combat tonnage, had more aircraft remaining, and were in physical possession of the battle zone... Arguments based on aircrew losses or who owned Guadalcanal are about something else – the campaign, not the battle.

In Prados’ view, the real story of the aftermath is that the Imperial Navy failed to exploit their hard-won victory although it is unclear how Japanese forces could have done so with such crippling losses of trained air crews.

|

| A group of Imperial Japanese Naval pilots lined up on the deck of an aircraft carrier during the Battle of Santa Cruz, probably being briefed before taking to their aircraft. |

|

| The crew of Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft carrier Shokaku fight fires after the ship was hit by American carrier aircraft bombs during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. |

|

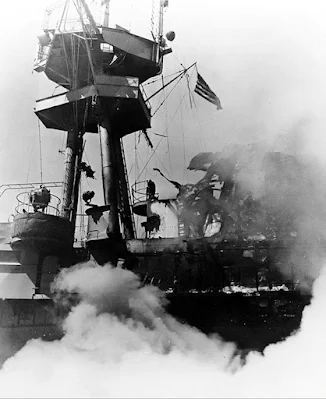

| The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) on fire after a Japanese D3A1 “Val” dive-bomber crashed into her island during the Battle of Santa Cruz on 26 October 1942. |

|

| The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) under attack and burning during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. Anti-aircraft shell bursts are visible above the carrier. |

|

| The damaged U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) during the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands with the destroyer USS Russell (DD-414) alongside ready to take off her crew. |

|

| The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8), severely listing, is abandoned by her crew at about 17:00 hrs during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. |

|

| The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) maneuvers to avoid Japanese bombs during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. |

|

| A Japanese bomb explodes off the port side of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942. |

|

| Two Japanese Nakajima B5N2 Kate torpedo bombers fly near the U.S. battleship USS South Dakota (BB-57) during the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942 in the Southwest Pacific. |

|

| The U.S. Navy battleship USS South Dakota (BB-57), foreground, and a destroyer maneuvering at high speed during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. |

|

| The U.S. Navy battleship USS South Dakota (BB-57) underway at high speed while firing her anti-aircraft guns during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. |

|

| The U.S. Navy light cruiser USS Juneau (CL-52) firing at attacking Japanese Aichi D3A dive bombers during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. |

|

| The U.S. Navy destroyer USS Smith (DD-378) is hit by a crashing Japanese torpedo plane, during an attack on USS Enterprise (CV-6), Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942. |

|

| The crew of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) conducts burial-at-sea on 27 October 1942, for 44 crewmen killed during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands the day before. |