Operation Ke was the largely successful withdrawal of Japanese forces from Guadalcanal, concluding the Guadalcanal Campaign of World War II. The operation took place between 14 January and 7 February 1943, and involved both army and navy forces under the overall direction of the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters (IGH). Commanders of the operation included Isoroku Yamamoto and Hitoshi Imamura.

The Japanese decided to withdraw and concede Guadalcanal to Allied forces for several reasons. All previous attempts by the Japanese army to recapture Henderson Field, the airfield on Guadalcanal in use by Allied aircraft, had been repulsed with heavy losses. Japanese ground forces on the island had been reduced from 36,000 to 11,000 through starvation, disease, and battle casualties. Japanese naval forces in the area were also suffering heavy losses attempting to reinforce and resupply the ground forces on the island. These losses, plus the projected resources needed for further attempts to recapture Guadalcanal, were affecting strategic security and operations in other areas of the Japanese Empire. The decision to withdraw was endorsed by Emperor Hirohito on 31 December 1942.

The operation began on 14 January 1943 with the delivery of a battalion of infantry troops to Guadalcanal to act as rearguard for the evacuation. Around the same time, Japanese army and navy air forces began an air superiority campaign around the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. During the air campaign, a US cruiser was sunk in the Battle of Rennell Island. Two days later, Japanese aircraft sank a US destroyer near Guadalcanal. The actual withdrawal was carried out on the nights of 1, 4, and 7 February by destroyers.

At a cost of one destroyer sunk and three damaged, the Japanese evacuated 10,652 men from Guadalcanal. 600 of those died during the evacuation, and 3,000 more required extensive hospital care. On 9 February, Allied forces realized that the Japanese were gone and declared Guadalcanal secure, ending the six-month campaign for control of the island.

Background

On 7 August 1942, the US 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the US and Australia, and to secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of capturing or neutralizing the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.

Taking the Japanese by surprise, by nightfall on 8 August the Allied troops (mainly United States Marine Corps) secured Tulagi and nearby small islands as well as the Japanese airfield under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. The Allies later renamed it “Henderson Field.” Allied aircraft operating out of Henderson were called the “Cactus Air Force” (CAF) after the Allied code name for Guadalcanal.

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters (IGH) assigned the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA) 17th Army, a corps-sized command headquartered at Rabaul under the command of Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, the task of retaking Guadalcanal. Because of the threat by CAF aircraft, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was unable to use large, slow transport ships to deliver troops and supplies to the island. Instead, warships based at Rabaul and the Shortland Islands were used to carry forces to Guadalcanal. The Japanese warships, mainly light cruisers and destroyers from the Eighth Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, were usually able to make the round trip down “The Slot” to Guadalcanal and back in a single night, thereby minimizing their exposure to CAF air attack. These high-speed warship runs to Guadalcanal occurred throughout the campaign and were later called the “Tokyo Express” by Allied forces and “Rat Transportation” by the Japanese.

Using forces delivered to Guadalcanal in this manner, the Japanese army tried three times to retake Henderson Field, but was defeated each time. After the third failure, an attempt by the IJN to deliver the rest of the IJA 38th Infantry Division and its heavy equipment failed during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal from 12–15 November. Because of this failure, the Japanese cancelled their next planned attempt to recapture Henderson Field.

In mid-November, Allied forces attacked the Japanese at Buna-Gona in New Guinea. Japanese Combined Fleet naval leaders, headquartered at Truk and under the overall command of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, felt Allied advances in New Guinea posed a greater threat to the security of the Japanese Empire than an Allied military presence in the southern Solomons. Therefore, Combined Fleet naval staff officers began to prepare plans for abandoning Guadalcanal and shifting priorities and resources to operations around New Guinea. At this time, the navy did not inform the army of their intentions in this regard.

As December began, the Japanese experienced considerable difficulty in keeping their troops on Guadalcanal resupplied because of Allied air and naval attacks on the Japanese supply chain of ships and bases. The few supplies delivered to the island were not enough to sustain Japanese troops, who by 7 December were losing about 50 men each day from malnutrition, disease, and Allied ground or air attacks. The Japanese had delivered almost 30,000 army troops to Guadalcanal since the campaign began, but by December only about 20,000 of that number were still alive, and only about 12,000 remained more or less fit for combat duty, with the rest incapacitated by battle wounds, disease, or malnutrition.

The IJN continued to suffer losses and damage to its ships in attempting to keep the Japanese on Guadalcanal resupplied. One destroyer was sunk by American warships at the Battle of Tassafaronga on 30 November. Another destroyer plus a submarine were sunk and two destroyers damaged by American PT boat and CAF air attacks during subsequent resupply missions from 3–12 December. Compounding the navy’s frustration, very few of the supplies carried on these missions actually reached Japanese army forces on the island. Combined Fleet leaders began telling their army counterparts the losses and damage to warships engaged in the resupply effort threatened future strategic plans for protecting the Japanese Empire.

Decision to Withdraw

Throughout November, Japan’s top military leaders at the IGH in Tokyo continued to openly support further efforts to retake Guadalcanal from Allied forces. At the same time, however, lower-ranking staff officers began to discreetly discuss abandoning the island. Takushiro Hattori and Masanobu Tsuji, each of whom had recently visited Guadalcanal, told their colleagues on the staff that any further attempt to retake the island was a lost cause. Ryūzō Sejima reported that the attrition of IJA troop-strength on Guadalcanal was so unexpectedly severe that future operations would be untenable. On 11 December, two staff officers, IJN Commander Yuji Yamamoto and IJA Major Takahiko Hayashi returned to Tokyo from Rabaul and confirmed Hattori’s, Tsuji’s, and Sejima’s reports. They further reported that most of the IJN and IJA officers at Rabaul appeared to support abandoning Guadalcanal. Around this time, Japan’s War Ministry informed the IGH that there was an insufficient amount of shipping to support both the effort to retake Guadalcanal and transport strategic resources to maintain Japan’s economy and military forces.

On 19 December, a delegation of IGH staff officers, led by IJA Colonel Joichiro Sanada, chief of the IGH’s operations section, arrived at Rabaul for discussions about future plans concerning New Guinea and Guadalcanal. Hitoshi Imamura, commander of the 8th Area Army in charge of IJA operations in New Guinea and the Solomons, did not directly recommend a withdrawal from Guadalcanal but openly and clearly described the current difficulties involved with any further attempts to retake the island. Imamura also stated that any decision to withdraw should include plans to evacuate as many of the soldiers from Guadalcanal as possible.

Sanada returned to Tokyo on 25 December and recommended to the IGH that Guadalcanal be abandoned immediately and all priority given to the campaign in New Guinea. The IGH’s top leaders agreed with Sanada’s recommendation on 26 December and ordered their staffs to begin drafting plans for the withdrawal from Guadalcanal and establishment of a new defense line in the central Solomons.

On 28 December, General Hajime Sugiyama and Admiral Osami Nagano personally informed Emperor Hirohito of the decision to withdraw from Guadalcanal. On 31 December, the Emperor formally endorsed the decision.

Plan and Forces

On 3 January, IGH informed the 8th Area Army and the Combined Fleet of the decision to withdraw from Guadalcanal. By 9 January, the Combined Fleet and 8th Area Army staffs together completed the plan, officially called Operation Ke after a mora in Japanese Kana vocabulary, to execute the evacuation.

The plan called for a battalion of army infantry to land by destroyer on Guadalcanal around 14 January to act as a rear guard during the evacuation. The 17th Army was to begin withdrawing to the western end of the island about 25 or 26 January. An air superiority campaign around the southern Solomons would begin on 28 January. The 17th Army would be picked up in three lifts by destroyers the first week of February with a target completion date of 10 February. At the same time, Japanese air and naval forces would conduct conspicuous maneuvers and minor attacks around New Guinea and the Marshall Islands along with deceptive radio traffic to try to confuse the Allies as to their intentions.

Yamamoto detailed aircraft carriers Junyō and Zuihō, battleships Kongō and Haruna — with four heavy cruisers and a destroyer as the screening force — under Nobutake Kondō to provide distant cover for Ke around Ontong Java in the northern Solomons. The evacuation runs were to be carried out by Mikawa’s 8th Fleet, consisting of heavy cruisers Chōkai and Kumano, light cruiser Sendai, and 21 destroyers. Mikawa’s destroyers were charged with conducting the actual evacuation. Yamamoto expected that at least half of Mikawa’s destroyers would be sunk during the operation.

Supporting the air superiority portion of the operation were the IJN’s 11th Air Fleet and the IJA’s 6th Air Division, based at Rabaul with 212 and 100 aircraft, respectively. 64 aircraft from carrier Zuikaku’s air group were also temporarily assigned to Rabaul. An additional 60 floatplanes from the IJN’s “R” Area Air Force, based at Rabaul, Bougainville, and the Shortland Islands, brought the total number of Japanese aircraft involved in the operation to 436. The combined Japanese warship and naval air units in the area formed the Southeast Area Fleet, commanded by Jinichi Kusaka at Rabaul.

Opposing the Japanese and under the command of United States Navy Admiral William Halsey, Jr., commander of Allied forces in the South Pacific, were fleet carriers USS Enterprise and Saratoga, six escort carriers, three fast battleships, four old battleships, 13 cruisers, and 45 destroyers. In the air, the 13th Air Force numbered 92 fighters and bombers under United States Army Brigadier General Nathan F. Twining and the CAF on Guadalcanal counted 81 aircraft under US Marine Brigadier General Francis P. Mulcahy. Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch was overall commander of Aircraft South Pacific. The air units of the fleet and escort carriers added another 339 aircraft. In addition, 30 heavy bombers were stationed in New Guinea with sufficient range to conduct missions over the Solomon Islands. In total, the Allies possessed around 539 aircraft available to oppose the Ke operation.

By the first week of January, disease, starvation, and battle had reduced Hyakutake’s command to about 14,000 troops, with many of them too sick and malnourished to fight. The 17th Army possessed three operable field cannon and a severe shortage of artillery shells. In contrast, the Allied commander on the island, US Army Major General Alexander Patch, fielded a combined force of US Army and US Marines, designated the XIV Corps, totaling 50,666 men. At Patch’s disposal were 167 artillery weapons, including 75 mm (2.95 in), 105 mm (4.13 in), and 155 mm (6.1 in) howitzers, and plentiful stocks of shells.

Operation

Preparation

On 1 January, the Japanese military changed their radio communication codes, making it more difficult for Allied intelligence, which had heretofore partially broken Japanese radio ciphers, to divine Japanese intentions and movement. As January progressed, Allied reconnaissance and radio traffic analysis noted the buildup of ships and aircraft at Truk, Rabaul, and the Shortland Islands. Allied analysts determined that the increased radio traffic in the Marshalls was a deception meant to divert attention from an operation about to take place in either New Guinea or the Solomons. Allied intelligence personnel, however, misinterpreted the nature of the operation. On 26 January, the Allied Pacific Command’s intelligence section informed Allied forces in the Pacific that the Japanese were preparing for a new offensive, called Ke, in either the Solomons or New Guinea.

On 14 January, an Express mission of nine destroyers delivered the Yano Battalion, designated as the rear guard for the Ke evacuation, to Guadalcanal. The battalion, commanded by Major Keiji Yano, consisted of 750 infantry and a battery of mountain guns crewed by another 100 men. Accompanying the battalion was Lieutenant Colonel Kumao Imoto, representing the 8th Area Army, who was to deliver the evacuation order and plan to Hyakutake. The 17th Army had not yet been informed of the decision to withdraw. CAF and 13th Air Force air attacks on the nine destroyers during their return trip damaged destroyers Arashi and Tanikaze and destroyed eight Japanese fighters escorting the convoy. Five American aircraft were shot down.

Late on 15 January, Imoto reached 17th Army’s headquarters at Kokumbona and informed Hyakutake and his staff of the decision to withdraw from the island. Grudgingly accepting the order on the 16th, the 17th Army staff communicated the Ke evacuation plan to their forces on the 18th. The plan directed the 38th Division, which was currently defending against an American offensive on ridges and hills in the interior of the island, to disengage and withdraw towards Cape Esperance on the western end of Guadalcanal beginning on the 20th. The 38th’s retirement would be covered by the 2nd Infantry Division, in place on Guadalcanal since October 1942, and the Yano Battalion, both of which would then follow the 38th westward. Any troops unable to move were encouraged to kill themselves to “uphold the honor of the Imperial Army.”

It is a very difficult task for the army to withdraw under existing circumstances. However, the orders of the Area Army, based upon orders of the Emperor, must be carried out at any cost. I cannot guarantee it can be completely carried out.” —Harukichi Hyakutake, 16 January 1943

Withdrawal Westward

Patch initiated a new offensive just as the 38th Division began to withdraw from the inland ridges and hills that it had occupied. On 20 January, the 25th Infantry Division, under Major General J. Lawton Collins, attacked several hills, designated Hills 87, 88, and 89 by the Americans, that formed a ridge that dominated Kokumbona. Encountering much lighter resistance than anticipated, the Americans seized the three hills by the morning of 22 January. Shifting forces to exploit the unexpected breakthrough, Collins quickly continued the advance and captured the next two hills, 90 and 91, by nightfall, placing the Americans in position to isolate and capture Kokumbona and trap the Japanese 2nd Division.

Reacting quickly to the situation, the Japanese hurriedly evacuated Kokumbona and ordered the 2nd Division to retire westward immediately. The Americans captured Kokumbona on 23 January. Although some Japanese units were trapped between the American forces and destroyed, most of the 2nd Division’s survivors escaped.

Still fearing a renewed and reinforced Japanese offensive, Patch committed the equivalent of only one regiment at a time to attack the Japanese forces west of Kokumbona, keeping the rest near Lunga Point to protect the airfield. The terrain west of Kokumbona favored the Japanese efforts to delay the Americans as the rest of the 17th Army continued its withdrawal towards Cape Esperance. The American advance was hemmed into a corridor only 300–600 yd (270–550 m) wide between the ocean and the thick, inland jungle and steep coral ridges. The ridges, running perpendicular to the coast, paralleled numerous streams and creeks that crossed the corridor with “washboard regularity.”

On 26 January, a combined U.S. Army and Marine unit called the Composite Army-Marine (CAM) Division advancing westward encountered the Yano Battalion at the Marmura River. Yano’s troops temporarily halted the CAM’s advance and then slowly withdrew westward over the next three days. On 29 January, the Yano retreated across the Bonegi River, where soldiers from the 2nd Division had constructed another defensive position.

The Japanese defenses at the Bonegi held up the American advance for almost three days. On 1 February, with help from a shore bombardment by the destroyers USS Wilson and Anderson, the Americans successfully crossed the river but did not immediately press the advance westward.

Air Campaign

The Ke air superiority campaign began in mid-January with nightly harassment attacks on Henderson Field by 3–10 aircraft, causing little damage. On 20 January, a lone Kawanishi H8K bombed Espiritu Santo. On 25 January, the IJN sent 58 Zero fighters on a daylight raid to Guadalcanal. In response, the CAF sent aloft eight Wildcat and six P-38 fighters, which shot down four Zeros without loss.

A second large raid was conducted on 27 January by nine Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lily” light bombers escorted by 74 Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar” fighters from the IJA’s 6th Air Division from Rabaul. Twelve Wildcats, six P-38s, and 10 P-40s from Henderson met the raid over Guadalcanal. In the resulting action, the Japanese lost six fighters while the CAF lost one Wildcat, four P-40s, and two P-38s. The “Lilys” dropped their bombs on American positions around the Matanikau River, causing little damage.

Battle of Rennell Island

Believing that the Japanese were beginning a major offensive in the southern Solomons aimed at Henderson Field, Halsey responded by sending, beginning on 29 January, a resupply convoy to Guadalcanal supported by most of his warship forces, separated into five task forces. These five task forces included two fleet carriers, two escort carriers, three battleships, 12 cruisers, and 25 destroyers.

Screening the approach of the transport convoy was Task Force 18 (TF 18), under Rear Admiral Robert C. Giffen, with three heavy and three light cruisers, two escort carriers, and eight destroyers. A fleet carrier task force, centered on carrier USS Enterprise, steamed about 250 mi (220 nmi; 400 km) behind TF 18.

In addition to protecting the supply convoy, TF 18 was charged with rendezvousing with a force of four U.S. destroyers, stationed at Tulagi, at 21:00 on 29 January in order to conduct a sweep up “The Slot” north of Guadalcanal the next day to screen the unloading of the transports at Guadalcanal. However, the escort carriers were too slow to allow Giffen’s force to make the scheduled rendezvous, so Giffen left the carriers behind with two destroyers at 14:00 on 29 January and pushed on ahead.

Giffen’s force was being tracked by Japanese submarines, who reported on Giffen’s location and movement to their naval headquarters units. Around mid-afternoon, based on the submarine’s reports, 16 Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” from the 705 Air Group and 16 Mitsubishi G3M “Nell” bombers from the 701 Air Group took off from Rabaul carrying torpedoes to attack Giffen’s force, now located between Rennell Island and Guadalcanal.

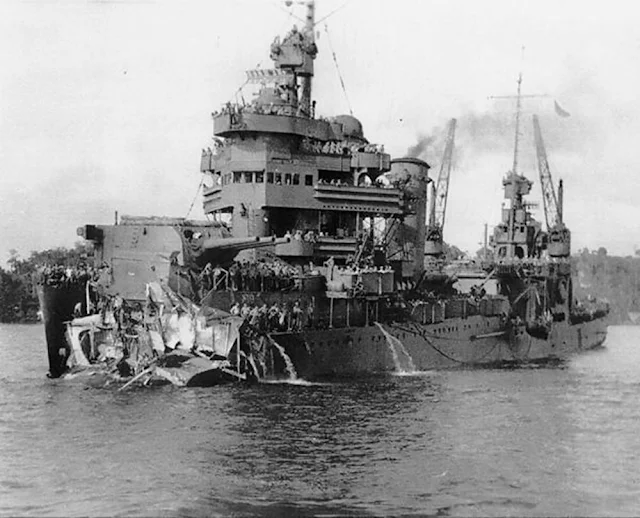

The torpedo bombers attacked Giffen’s ships in two waves between 19:00 and 20:00. Two torpedoes hit the heavy cruiser USS Chicago, causing heavy damage and bringing her to a dead stop. Three of the Japanese aircraft were shot down by anti-aircraft fire from Giffen’s ships. In response, Halsey sent a tug to take Chicago under tow and ordered Giffen’s task force to return to base the next day. Six destroyers were left behind to escort Chicago and the tugboat.

At 16:00 on 30 January, a flight of 11 Mitsubishi torpedo bombers from the 751 Air Group, based at Kavieng and staging through Buka, attacked the force towing Chicago. Fighter aircraft from Enterprise shot down eight of them, but most of the Japanese aircraft were able to release their torpedoes before crashing. One torpedo hit the destroyer USS La Vallette, causing heavy damage. Four more torpedoes hit Chicago, sinking her.

The transport convoy reached Guadalcanal and successfully unloaded its cargo on 30–31 January. The rest of Halsey’s warships took station in the Coral Sea south of the Solomons to wait for the approach of any Japanese warship forces supporting what the Allies believed to be an imminent offensive. The departure of TF 18 from the Guadalcanal area removed a significant potential threat to the Ke operation.

At 18:30 on 29 January, two corvettes from the Royal New Zealand Navy, Moa and Kiwi, intercepted the Japanese submarine I-1, which was attempting a supply run, off of Kamimbo on Guadalcanal. The two corvettes rammed and sank I-1 after a 90-minute battle.

First Evacuation Run

Leaving his cruisers at Kavieng, Mikawa gathered all 21 of his destroyers at the Japanese naval base in the Shortlands on 31 January to begin the evacuation runs. Rear Admiral Shintaro Hashimoto was placed in charge of this group of destroyers, titled the Reinforcement Unit. The “R” Area Air Force’s 60 floatplanes were tasked with scouting for the Reinforcement Unit and helping defend against Allied PT boat attacks during the nighttime evacuation runs. Allied B-17 bombers attacked the Shortlands anchorage on the morning of 1 February, causing no damage and losing four aircraft to Japanese fighters. This same day, the IJA’s 6th Air Division raided Henderson Field with 23 “Oscars” and six “Lilys” but caused no damage and suffered the loss of one fighter.

Believing that the Japanese might be retreating to the south coast of Guadalcanal, on the morning of 1 February Patch landed a reinforced battalion of army and Marine troops, about 1,500 men under the command of Colonel Alexander George, at Verahue on Guadalcanal’s south coast. The U.S. troops were delivered to the landing location by a naval transport force of six landing craft tanks and one transport destroyer (USS Stringham), escorted by four other destroyers (the same destroyers that were to have joined TF 18 three days earlier). A Japanese reconnaissance aircraft spotted the naval landing force. Believing that the force posed a threat to that night’s scheduled evacuation run, an airstrike of 13 Aichi D3A2 “Val” dive bombers escorted by 40 Zeros departed Buin, Bougainville to attack the ships.

Mistaking the Japanese strike aircraft as friendly, the U.S. destroyers withheld fire until the “Val”s began their attack. Beginning at 14:53, destroyer USS De Haven was rapidly hit by three bombs and sank almost immediately 2 mi (1.7 nmi; 3.2 km) south of Savo Island with the loss of 167 of her crew, including her captain. Destroyer USS Nicholas was damaged by several near-misses. Five “Val”s and three Zeros were lost to anti-aircraft fire and CAF fighters. The CAF lost three Wildcats in the engagement.

Hashimoto departed the Shortlands at 11:30 on 1 February with 20 destroyers for the first evacuation run. Eleven destroyers were designated as transports screened by the other nine. The destroyers were attacked in the late afternoon near Vangunu by 92 CAF aircraft in two waves. The Allied fliers scored a near miss on Makinami, Hashimoto’s flagship, heavily damaging it. Four CAF aircraft were shot down. Hashimoto transferred to Shirayuki and detached Fumizuki to tow Makinami back to base.

Eleven U.S. PT boats awaited Hashimoto’s destroyers between Guadalcanal and Savo Island. Beginning at 22:45, Hashimoto’s warships and the PT boats engaged in a series of running battles over the next three hours. Hashimoto’s destroyers, with help from “R” Area aircraft, sank three of the PT boats.

In the meantime, the transport destroyers arrived off of two pick-up locations at Cape Esperance and Kamimbo at 22:40 and 24:00 respectively. Japanese naval personnel ferried the waiting troops out to the destroyers in barges and landing craft. Rear Admiral Tomiji Koyanagi, second-in-command of the Reinforcement Unit, described the evacuees: “They wore only the remains of clothes that were so soiled their physical deterioration was extreme. Probably they were happy but they showed no expression. Their digestive organs were so completely destroyed, we couldn’t give them good food, only porridge.” Another officer added that, “Their buttocks were so emaciated that their anuses were completely exposed, and on the destroyers that picked them up they suffered from constant and uncontrolled diarrhea.”

After embarking 4,935 soldiers, mainly from the 38th Division, the transport destroyers ceased loading at 01:58 and prepared to depart for the return trip to the Shortlands. About this time, Makigumo, one of the screening destroyers, was suddenly wracked by a large explosion, caused by either a PT boat torpedo or a naval mine. Informed that Makigumo was immobilized, Hashimoto ordered her abandoned and scuttled. During the return trip, the Reinforcement Unit was attacked by CAF aircraft at 08:00, but sustained no damage and arrived at the Shortlands without further incident at 12:00 on 2 February.

Second and Third Evacuation Runs

On 4 February, Patch ordered the 161st Infantry Regiment to replace the 147th at the front and resume the advance westward. The Yano battalion retreated to new positions at the Segilau River and troops were sent to block the advance of George’s force along the south coast. Meanwhile, Halsey’s carrier and battleship task forces remained just beyond Japanese air attack range about 300 mi (260 nmi; 480 km) south of Guadalcanal.

Kondo sent two of his force’s destroyers, Asagumo and Samidare, to the Shortlands to replace the two destroyers lost in the first evacuation run. Hashimoto led the second evacuation mission with 20 destroyers south toward Guadalcanal at 11:30 on 4 February. The CAF attacked Hashimoto in two waves beginning at 15:50 with a total of 74 aircraft. Bomb near-misses heavily damaged Maikaze, and Hashimoto detached Nagatsuki to tow her back to Shortland. The CAF lost 11 aircraft in the attack while the Japanese lost one Zero.

The U.S. PT boats did not sortie to attack Hashimoto’s force this night and the loading went uneventfully. The Reinforcement Force embarked Hyakutake, his staff, and 3,921 men, mainly from the 2nd Division, and reached Bougainville without incident by 12:50 on 5 February. A CAF airstrike launched that morning failed to locate Hashimoto’s force.

Believing that the Japanese operations on 1 and 4 February had been reinforcement, not evacuation missions, the American forces on Guadalcanal proceeded slowly and cautiously, advancing only about 900 yd (820 m) each day. George’s force halted on 6 February after advancing to Titi on the south coast. On the north coast, the 161st finally began their attack westward at 10:00 on 6 February and reached the Umasani River the same day. At the same time, the Japanese were withdrawing their remaining 2,000 troops to Kamimbo.

On 7 February, the 161st crossed the Umasani and reached Bunina, about 9 mi (7.8 nmi; 14 km) from Cape Esperance. George’s force, now commanded by George F. Ferry, advanced from Titi to Marovovo and dug in for the night about 2,000 yd (1,800 m) north of the village.

Aware of the presence of Halsey’s carriers and other large warships near Guadalcanal, the Japanese considered canceling the third evacuation run, but decided to go ahead as planned. Kondo’s force closed to within 550 mi (480 nmi; 890 km) of Guadalcanal from the north to be ready in case Halsey’s warships attempted to intervene. Hashimoto departed the Shortlands with 18 destroyers midday of 7 February, this time taking a course south of the Solomons instead of down the Slot. A CAF strike force of 36 aircraft attacked Hashimoto at 17:55, heavily damaging Isokaze with a bomb near miss. Isokaze retired escorted by Kawakaze. The Allies and the Japanese each lost one aircraft in the attack.

Arriving off Kamimbo, Hashimoto’s force loaded 1,972 soldiers by 00:03 on 8 February, unhindered by the U.S. Navy. For an additional 90 minutes, destroyer crewmen rowed their boats along the shore calling out again and again to make sure no one was left behind. At 01:32, the Reinforcement Group left Guadalcanal in its wake and reached Bougainville without incident at 10:00, completing the operation.

Aftermath

At dawn on 8 February, the U.S. Army forces on both coasts resumed their advances, encountering only a few sick and dying Japanese soldiers. Patch now realized that the Tokyo Express runs over the last week were evacuation, not reinforcement missions. At 16:50 on 9 February, the two American forces met on the west coast at the village of Tenaro. Patch sent a message to Halsey stating, “Total and complete defeat of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal effected 16:25 today...the Tokyo Express no longer has a terminus on Guadalcanal.”

The Japanese had successfully evacuated a total of 10,652 men from Guadalcanal, about all that remained of the 36,000 total troops sent to the island during the campaign. Six hundred of the evacuees succumbed to their injuries or illnesses before they could receive sufficient medical care. Three thousand more required lengthy hospitalization or recuperation. After receiving word of the completion of the operation, Yamamoto commended all the units involved and ordered Kondo to return to Truk with his warships. The 2nd and 38th Divisions were shipped to Rabaul and partially reconstituted with replacements. The 2nd Division was relocated to the Philippines in March 1943 while the 38th was assigned to defend Rabaul and New Ireland. The 8th Area Army and Southeast Area Fleet reoriented their forces to defend the central Solomons at Kolombangara and New Georgia and prepared to send the reinforcements, mainly consisting of the 51st Infantry Division, originally detailed for Guadalcanal to New Guinea. The 17th Army was rebuilt around the 6th Infantry Division and headquartered on Bougainville. A few Japanese stragglers remained on Guadalcanal, many of whom were subsequently killed or captured by Allied patrols. The last known Japanese holdout surrendered in October 1947.

In hindsight, historians have faulted the Americans, especially Patch and Halsey, for not taking advantage of their ground, aerial, and naval superiority to prevent the successful Japanese evacuation of most of their surviving forces from Guadalcanal. Said Chester Nimitz, commander of Allied forces in the Pacific, of the success of Operation Ke, “Until the last moment it appeared that the Japanese were attempting a major reinforcement effort. Only the skill in keeping their plans disguised and bold celerity in carrying them out enabled the Japanese to withdraw the remnants of the Guadalcanal garrison. Not until all organized forces had been evacuated on 8 February did we realize the purpose of their air and naval dispositions.”

Nevertheless, the successful campaign to recapture Guadalcanal from the Japanese was an important strategic victory for the U.S. and its allies. Building on their success at Guadalcanal and elsewhere, the Allies continued their campaign against Japan, ultimately culminating in Japan’s defeat and the end of World War II.

References

Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Naval Institute Press.

Crenshaw, Russell Sydnor (1998). South Pacific Destroyer: The Battle for the Solomons from Savo Island to Vella Gulf. Naval Institute Press.

D'Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub.

Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press.

Frank, Richard B. (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Penguin Group.

Griffith, Samuel B. (1963). The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Hayashi, Saburo (1959). Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Association.

Jersey, Stanley Coleman (2008). Hell's Islands: The Untold Story of Guadalcanal. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press.

Letourneau, Roger; Letourneau, Dennis (2012). Operation Ke: The Cactus Air Force and the Japanese Withdrawal from Guadalcanal. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Dr. Duncan Anderson (consultant editor). Oxford and New York: Osprey.

Tagaya, Osamu (2001). Mitsubishi Type 1 "Rikko" 'Betty' Units of World War 2. New York: Osprey.

Toland, John (2003) [First published in 1970]. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936–1945. New York: The Modern Library.

|

| Colonel Takushiro Hattori, Chief of Operations Planning Staffs, Imperial Japanese Army, July 1941 through February 1945. |

|

| Japanese destroyer Asagumo. (From A503 FM30-50 booklet for identification of ships, published by the Division of Naval Intelligence of the Navy Department of the United States) |

|

| Cemetery on Guadalcanal, photographed in 1945, for both Allied and Japanese remains. (US Army photo) |